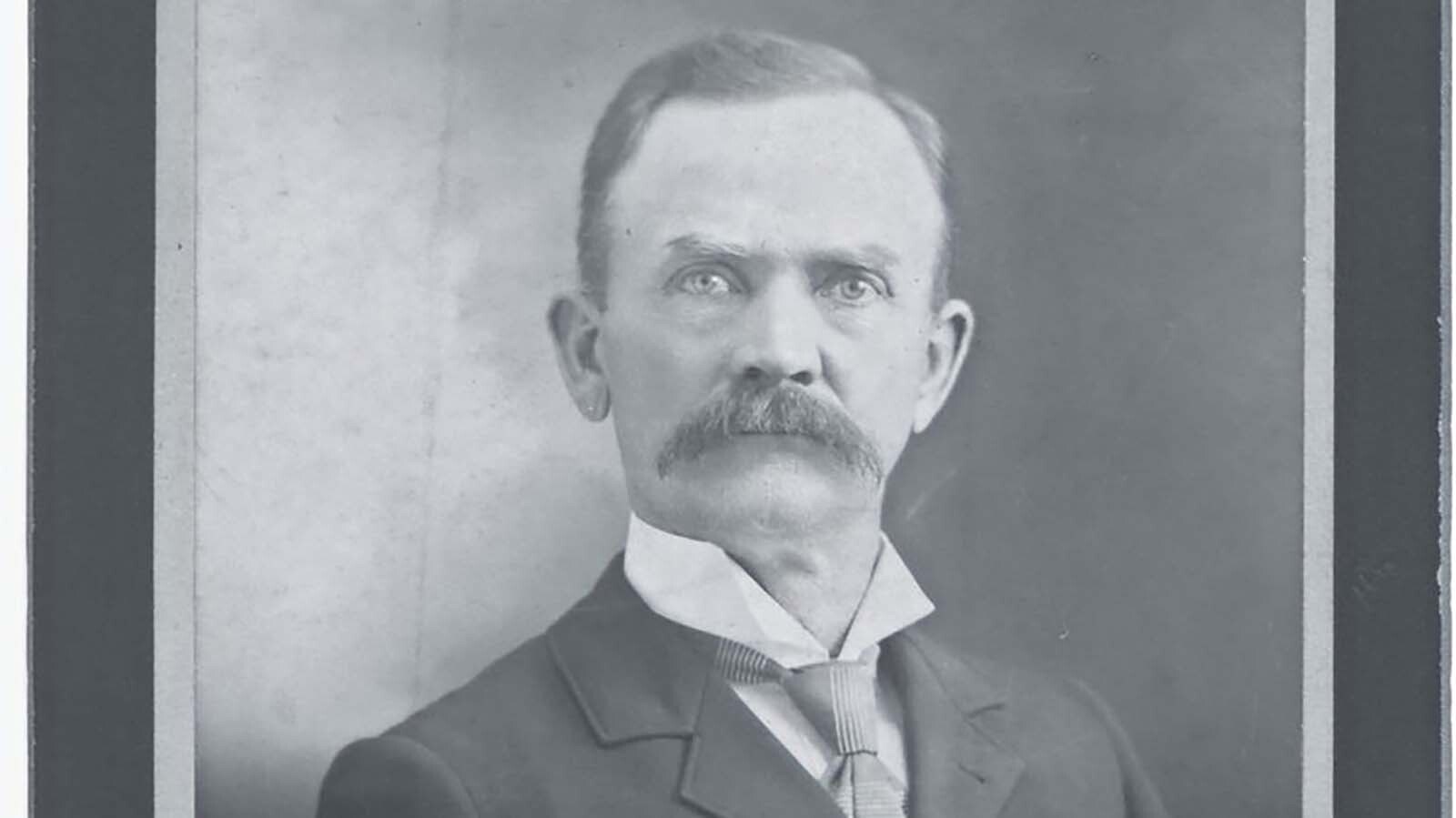

Oliver Perry Hanna, better known as O.P., was an orphan who grew up on dime novel adventures of Louis Whestel, Wild Cat Joe and Indian Dick.

As a 16-year-old, Hanna hired on to train oxen for Jake Goff, an early pioneer who was heading west from Illinois.

In barely contained excitement, Hanna started the long trek west to pursue his boyhood dreams.

To his surprise, Hanna found more adventure than he ever imagined as a frontiersman, Indian fighter, and pioneer of the territory of Wyoming.

In his later years, Hanna left Wyoming to settle in Long Beach, California, with his family, but his heart remained in the Big Horn Mountains.

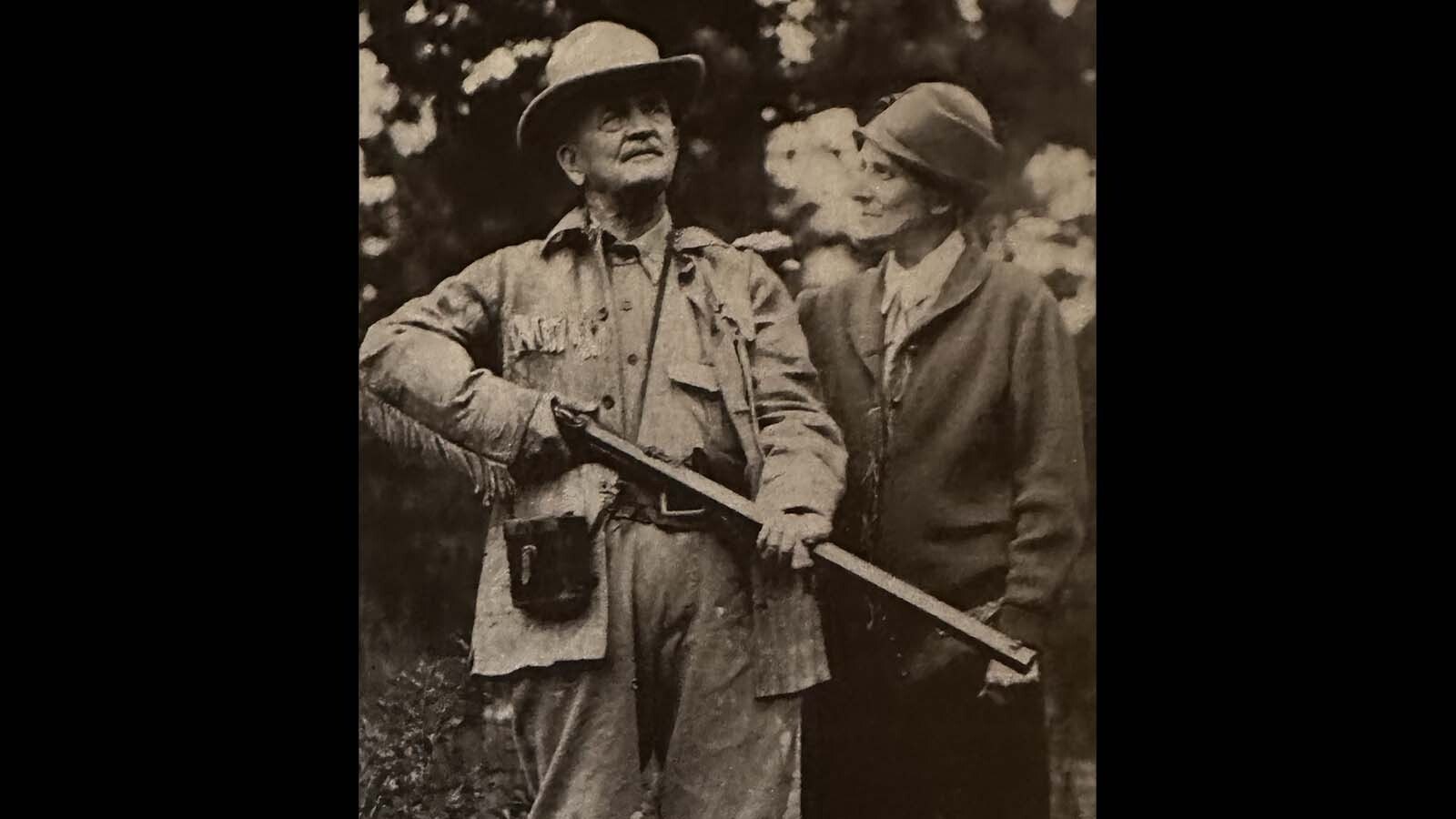

In June 1926, the 75-year-old Hanna returned to Wyoming to attend the Custer Semi-Centennial Celebration, and memories flooded back.

Driving along the Custer Highway, Hanna passed the spot where 52 years before, he had helped bury his friend, Zac Yates, in the dead of night while they were surrounded by hundreds of Sitting Bull’s hostile warriors.

This memory stirred something within Hanna, and he sought out others who had been there.

Remembering these times vividly, Hanna went to the Crow Agency and discovered that all the Crow warriors he had fought alongside during the Bozeman-Rosebud Expedition had passed over “The Great Divide.”

The interpreter brought over an old Sioux chief who had instead fought against Hanna, rather than with him. Hanna said the two just stared at each other until finally the Sioux spoke.

“Brave man, heap good fight.”

“The words seemed like an echo of those early days that soon will be forgotten past,” Hanna said. “They recalled to me the words of Ben Walker that were as yet unfulfilled.”

Write It Up!

The desire to record his adventures was planted back in May 1874.

When Hanna was 23, he had just returned to Bozeman after three months of steady Indian fighting. Walker, a Hudson Bay Fur Co. trapper and his mentor, guided the returning men into a saloon and ordered drinks.

“Well boys, I hear you did some fighting down on the Rosebud,” Walker said.

Another trapper, Bill Hamilton, threw his gruesome trophies, a scalp and fingers, onto the bar.

“Yes, doesn’t this look like it?” Hamilton said. “Young Hanna swears it beat anything he ever read in Beadle’s Dime Novels.”

Walker laughed and then spoke the fateful words that spurred Hanna to record his adventures.

“Yes, boys. It’s the Big Horn country an’ some day some feller with book larnin’ will write it up,” Walker said.

By 1926, when Hanna returned to this Big Horn country, it had already been over half a century since those words were spoken but never recorded. As Hanna parted ways amicably with the Sioux who had once been his enemy, he realized that the ‘feller’ Walker spoke about had to be him.

Hanna’s subsequent manuscript remained relatively unknown until, in the 1980s, Sheridan historian Deck Hunter began researching the homesteaders of the Big Horn.

Hunter successfully tracked down Hanna’s only grandchild in California and discovered not only did the family have pictures, but they had written stories.

Charles Hanna Carter then donated a copy of his grandfather’s first-person accounts to the Wyoming Room at the Sheridan County Fulmer Public Library, preserving a valuable history of the area that would have otherwise been lost.

West Ho!

In his memoir, Hanna recounted famous people and events that he had witnessed firsthand.

When on his way with the ox train to help pioneer the Wild West, for instance, Hanna learned that Wild Bill Hickok and “Buffalo Bill” were along the route in Abilene, Kansas. It was Hanna’s first opportunity to see some of the real-life heroes he had only read about, and the teenager soon found the men in a saloon, playing cards.

“They both wore buckskin coats and were fine specimens of humanity,” Hanna said. “I determined right then to own a coat like theirs, though I wasn’t sure that I wanted to wear long hair.”

At the Republican River on his way to Cheyenne, Hanna killed his first buffalo and said he was the proudest boy in all the country, his adventure off to a fine start.

When they finally reached Cheyenne, it was the morning of July 4, 1867.

They were just in time for a great celebration as the last rail of the Union Pacific Railroad had just been laid into town from Omaha, Nebraska.

Hanna went on to become an eyewitness to many historic events as the West was just then being ‘tamed.’ One of these first adventures occurred when, still only 16, Hanna joined the gold rush in Alder Gulch, Montana.

There he met desperados such as Jim Plummer and George Ives, and he also rubbed elbows with prominent men such as Sam Ward and the wayward camp preacher, Colonel Woods.

Hanna’s life as a gold miner was short-lived, however.

Within just the second week, he was caught in a landslide and had to be dug out. After recovering from his bruises, he moved on and became a farmhand until he saved up enough money to outfit himself for Indian country.

A Teenage Frontiersman

In the summer of 1869, the teenage Hanna set off for Yellowstone country and more adventures. In Bozeman, then a small settlement of about 800 people, Hanna sought out the two most noted frontiersmen in the whole northwest, Ben Walker and Bill Hamilton.

The men were getting ready to head up to Clark’s Fork and Hanna mustered up his courage to ask them if he could go with them on the trapping trip.

“That is a bad Indian country over there and we don’t want any kids along with us if we get into a scrap with them,” the trappers told Hanna.

Hanna replied that he was looking for Indian fighting and they laughed at him. Eventually, Hanna proved his worth by working around their camp and making himself helpful, and the trappers agreed to let Hanna join them.

Under their tutelage, Hanna learned how to survive in the frontier and hunt beaver. Just as the men predicted, they were attacked by Indians and Hanna had to learn the skills of bandaging up his comrades after their first battle.

“This Indian fighting wasn’t what it’s cracked up to be,” Hanna said.

He discovered quickly that it was not as glamorous as his novels led him to think and most of his time was spent hiding and avoiding the gunshots.

This first attempt at trapping ended up with Hanna broke and wounded. However, it didn’t stop him and it made the teenager even more determined to succeed in this hostile land.

Found His Adventures

Over the years, Hanna explored the wilds of the Wyoming Territory, often in the company of Walker and other trappers. He camped in Yellowstone in 1870, when it was still being mapped, and survived many more Indian attacks.

In 1874, Hanna was recruited for the Bozeman-Big Horn-Rosebud expedition and barely escaped with his life. One incident from that time stood out to Hanna. He was stationed to guard a small hill and give the alarm if he saw any Indians.

“I had a pretty good horse and felt that I could reach camp all right in case of an attack,” Hanna said. “I had been there scarcely more than five minutes when I heard a shot and, looking back, I saw coming over a ridge not 200 yards away, about 30 Indians.”

Hanna jumped on his horse, bullets flying all about him. They hit his horse and he jumped off, hiding in a bunch of rocks. He was able to hold the attackers off until help came from camp.

Years later, in 1906, Hanna said he returned to the spot and picked up the fifty-caliber shells which he had fired at the Indians from his buffalo rifle. He kept the bullets as souvenirs.

Keeping The Memories Alive

Hanna went on to join the Battle of Big Horn at the Rosebud in the spring of 1876 and became a member of the Sibley expedition in June of that same year.

After General Armstrong Custer and his men were massacred, it was Hanna who led a reporter and pack train back to the site.

Officially, Bill Cody was the lead scout, but Hanna knew the area better from his trapping trips, and the two would later reminisce about how Cody nearly got everyone lost before Hanna was allowed to show the way.

After the Indian Wars were over, Hanna turned to ranching and cowboying.

He took out his own homestead and named the town of Big Horn City.

He married and started a family in the wilds of Wyoming and then relocated to Sheridan when the railroad laid their tracks. In that fledgling town, Hanna built a hotel before retiring to Long Beach, California.

Hanna is remembered as the original settler in Sheridan County and his adventures are preserved thanks to the prompting of the old trapper, Ben Walker, who said that someday, some ‘feller’ was going to record their stories.

Jackie Dorothy can be reached at jackie@cowboystatedaily.com.