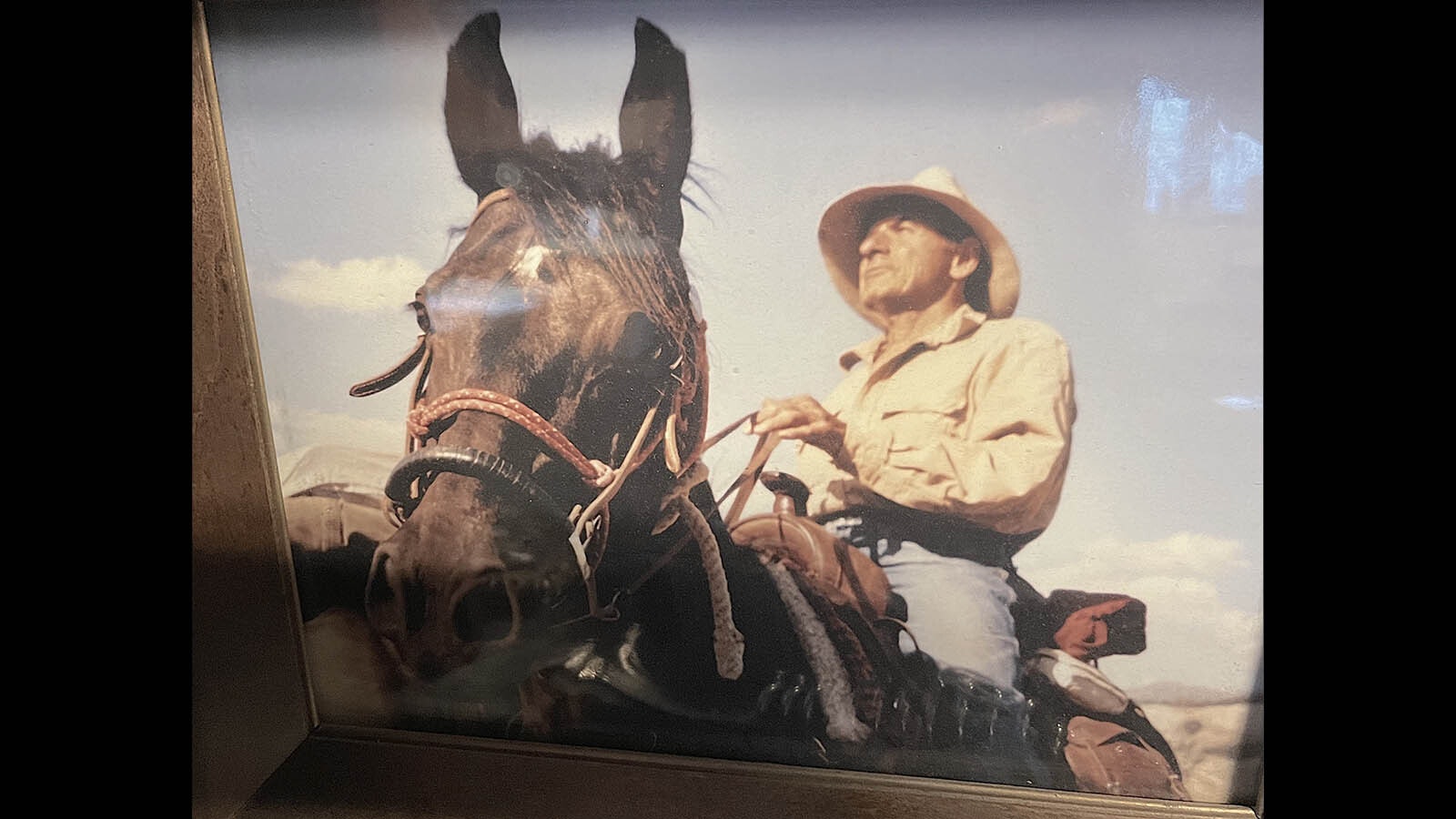

There was a time when Gaspari “Gap” Pucci was noted for his Sicilian background. He was an oddity — an Italian from South Philly cowboying out West in Wyoming.

But he followed his dream. He built a highly respected big game hunting outfit in Jackson Hole and spent almost four decades doing what he loved from the back of a horse.

His office was the Gros Ventre Wilderness, an unspoiled section of Bridger-Teton backcountry where few tread even today. It’s a roadless and wild 250-square-mile chunk of forest as rugged and remote as it gets anywhere in the continental U.S.

Nowadays what makes this 88-year-old special is the fact that he still lives like he does — straight-up cowboy. No phone, no internet, no modern amenities. Not even a fancy hay fork with the composite handle.

His tack room looks like an episode of “Pickers: Little House on the Prairie” edition. The bunkhouse was built in 1930 by Howard Bellew. It holds a worn saddle Gap estimates has about 40,000 miles on it. There are halters, headstalls and horseshoes from the Eisenhower era. Saddle blankets are older than the average rodeo contestant.

He Is The Lifestyle

The longtime Wyoming outfitter makes his home 17 miles south of Jackson on a 5-acre ranchette squeezed between a state elk feedground, national forest land and aggressively approaching Jackson Hole buildout. He bought the place in the disco era. He’ll die there.

Every day he chores around the homestead, caring for the last handful of his once 40-head string of horses. He bucks hay, chops holes in an iced-over spring so his stock can drink and keeps a rifle ready at the back door when the wolves get too close.

Nights, the old-time hand relives what was, watching black-and-white Westerns in reruns. He remembers what was by writing down his escapades by hand and gathering them into memoirs.

Two books published and a third on the way offer a fascinating glimpse into a man and his family carving out a way of life in Western Wyoming that reads like exaggerated folklore.

Fighting bears, lost in a blizzard, horses plummeting from a cliff edge down into a raging river below. Gap Pucci somehow survived it all and lived to tell about it.

“I don't know how I'm still here. The things I did. The way I lived,” Pucci says, slowly shaking another memory out of his head. “The good Lord and good horses are the only reasons I'm still breathing.”

Pucci is quite literally the last of his kind. His peers, as he often laments, are all gone. His way of life, outmoded and obsolete. Like him.

Coming To America

Pucci, the character, is summed up by tenacity, grit and any other adjective Louis L’Amour ever used in one of his pulp fiction Westerns. A living legend in the hunting world and a testament to the indefatigable human spirit.

The wiry Italian’s work ethic was instilled growing up an emigrant during the Depression. Like his father, and his father’s father, Pucci broke big rocks into smaller rocks with a 12-pound hammer all day long in a quarry.

The Puccis immigrated to the U.S. from Sciacca, Sicily, in the early 1900s. His ancestors were hunters and fishermen in the homeland. In America, the Puccis were reduced to little more than grunt work.

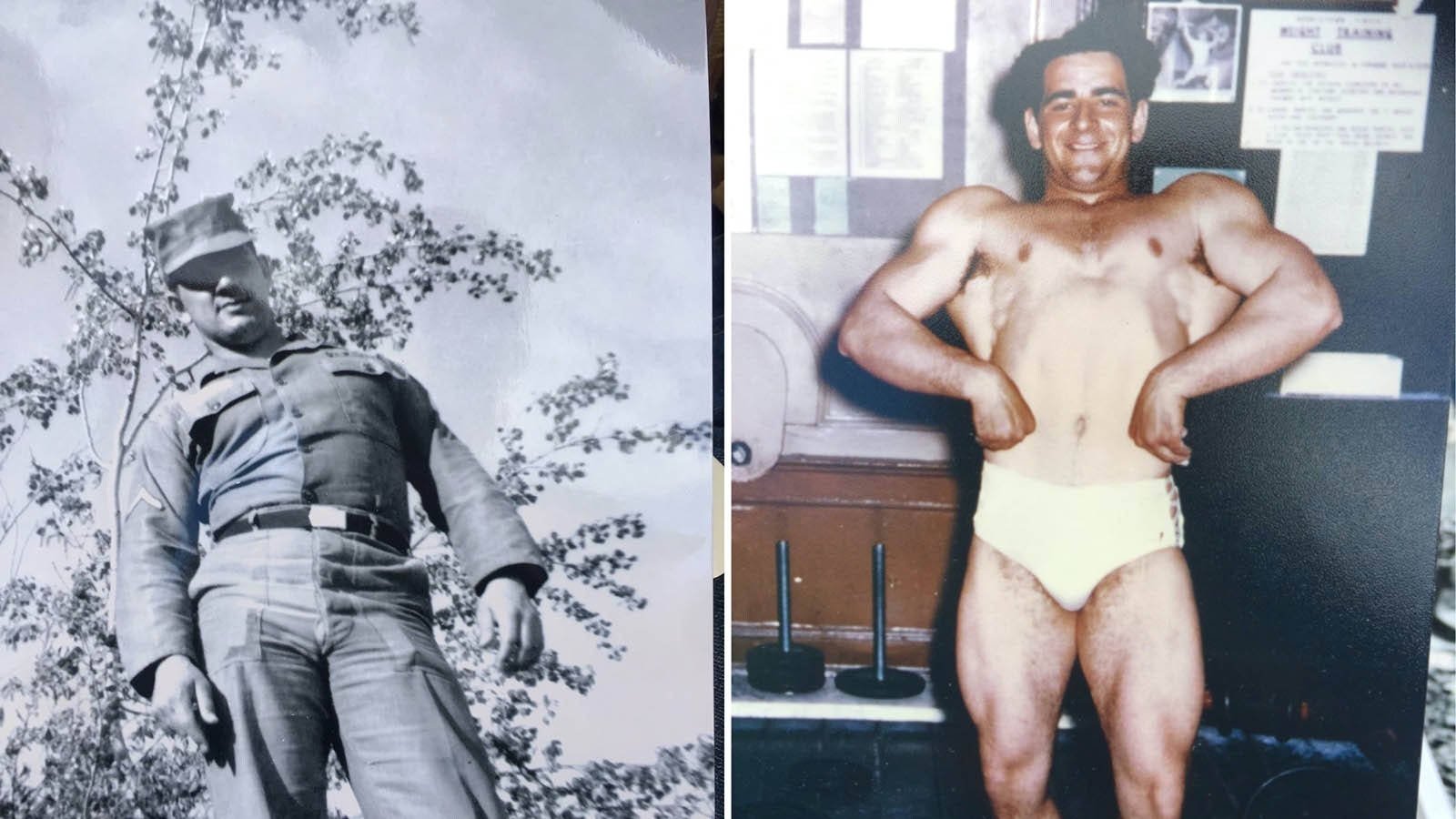

To keep out of trouble, Pucci took up competitive weightlifting and body building. He would later take a farrier course at Penn State University and pick up work at local harness racing tracks and area veterinarians.

Those jobs taught Pucci how to handle hotblooded stallions, a valuable lesson he would apply in his second life.

Still, through his teens and early 20s, Pucci had few aspirations beyond the quarry until the Vietnam War. If not for a stint in the Army, Pucci may never have left Black Horse, Pennsylvania, where he was born in 1935.

“Italians don't leave their families,” Pucci shared.

Fearful of Soviet Union invasion during the Cold War period, the U.S. set up a strike force unit in Point Barrow, Alaska, where Pucci was stationed from 1958-59. It was a frigid remote mountain outpost.

Pucci never encountered any Russians, but he got his first look at wild and untamed land unlike anything back East. Plus, he learned firsthand how to survive in challenging conditions.

“My hands were frostbitten all the time. I went snow blind. It was tough,” Pucci remembered. “We often slept with the wolves howling outside.”

While the rest of his company couldn’t wait to get out, Pucci couldn’t wait to get back. He was hooked. He simply had to get out West and seek a new life.

On To Wyoming, Hello Wilderness

Pucci eventually made his way to Utah, where he hired on with a sheepherding outfit high in the Uinta Mountains. From there, Pucci discovered Jackson, Wyoming.

He met his wife, Peggy McClung, while working at Albert Feuz’s V-V Cattle and Dude Ranch in Bondurant. They were married in 1965.

It may have well been 1865 because that’s how the newlyweds lived.

Gap carried Peggy over the threshold of a drafty log cabin built in the early 1900s far from civilization up Granite Creek. There was no running water. That had to be hauled in 5-gallon cans from the creek. The only heat source was a woodstove.

No phone, no TV, no connection to the outside world. The only transportation in winter was an unreliable snowmobile. When it wasn’t running, which was often, it was a 10-mile snowshoe hike to the pickup parked out at the highway. From there, it was another 25 miles to the nearest grocery store in Jackson.

Their closest neighbors were frequent visits from elk, moose and myriad other wildlife.

The Puccis loved it.

Gap would eventually pen his first book in 2011 about the experience. Titled “We Married Adventure,” the autobiography includes firsthand accounts of the hardships the couple endured.

“It was a matter of rugged endurance just to make a living. You couldn’t have any quit in you,” Pucci said. “Of course, I loved my work. To me, it was an adventure, not an ordeal.”

The Puccis managed the hot springs for the Forest Service, charging a dollar for a soak. Other than chasing off a few hippies now and then who poached the hot spring pool in the dead of night, it was a lonesome existence.

“I owned that cabin for 25 years, with a special use permit from the Forest Service. I was the first to keep the hot springs open in the winter,” Pucci said.

When it came time to leave, Pucci asked the Forest Service to buy the old cabin from him. It wouldn’t.

“Even 500 bucks. Give me something for the damn thing,” Pucci said. “They said no, so I took that place down log by log, board by board. I wasn’t going to let them have it for nothing.”

Living The Dream

Pucci’s ultimate dream was to open his own outfitting business. He worked for a few area outfitters, guiding hunters until he had a chance to buy his own business in 1975.

It wasn’t long before Pucci acquired Red Buescher’s hunting business and a basecamp in Granite Creek from Larry Moore, as well several other hunt camps in the Gros Ventre Wilderness.

He slowly grew his horse herd, hauled hay and horses in a 1948 green Dodge stock truck to his basecamp in the Gros Ventre. The old log home there would one day be recognized on the National Registry of Historical Places (No. 287) as the old John Wort/Gap Pucci hunting cabin.

He eventually would build his business into one of the premier hunting outfits in Jackson Hole, internationally renowned with clientele from around the world.

Crystal Creek Outfitters took its name from a pristine stream in a remote region of the Gros Ventre where Pucci would help thousands of eager hunters bag their elk, moose, bighorn sheep or bear.

The Puccis moved into the house Gap still lives in today. It was a hardscrabble homestead even then in the 1970s. Built in 1910, it was known as the Startled Doe Ranch for years when Arthur Welch and his wife lived there.

The Puccis had to add water and electricity. Once indoor plumbing was installed, the Pucci girls made a playhouse out of the old outhouse.

It was rustic living, but nothing compared to the places Gap spent up to eight months a year living out of.

‘Fire Will Keep You Alive’

For most of a calendar year, Pucci hung his hat in various homesteader cabins with enough space between the logs to allow the snow to blow in. Even those were uptown living compared to the high-mountain hunt camps where a canvas tent was all that kept a sleeping body from a hungry bear.

“It was more than once I had a grizzly tear up a tent — claw right through a wall and shred it to pieces, knock everything in camp all over the place,” Pucci said.

And then there was many a night when Pucci never made it back to camp at all.

“In those early younger years there were times I was too far from camp, so I’d just build a fire, sleep on the mountain, and return the next day,” Pucci said.

A good mountain man is always prepared for just about anything. Pucci was no exception. He packed several emergency items in his saddle bags.

"I’ve got some rawhide in there in case you need to fix a bridle or something, you'll need that. You always want to carry fire. I packed a little Sterno can for heat. And I never travel without a lighter. Fire will keep you alive,” Pucci said.

One thing Pucci never carried was a canteen of any kind.

“I never carried a water bottle in my entire life. It’s crazy how everyone hydrates today. You don’t need to drink every 15 to 20 minutes and neither do your horses,” Pucci claimed. “I would carry a little water cup and I knew where all the springs were.”

Before Gore-Tex made “Life Below Zero” bearable and North Face labeled anything done in a puffer as “Xtreme,” Pucci made a living outdoors and thought nothing of it. All in unpredictable mountain weather and surrounded by predators that wanted to make a big game kill as much as Pucci’s hunters.

On more than one occasion, grizzly bears scratched his canvas wall tent to pieces. Horses fell off sheer cliff walls into an icy river below. Autumn blizzards made finding the way back to camp impossible, so he hunkered down and rode it out buried in snow until it let up.

By his own account, Pucci should have been dead a few times over.

“I think back to some of those stories, the things I did and wrote about in my books. I must have been crazy,” Pucci said. “They are not embellished. I remember them clearly. And I can't believe I am still alive after all that.”

A Bear Called Scarface

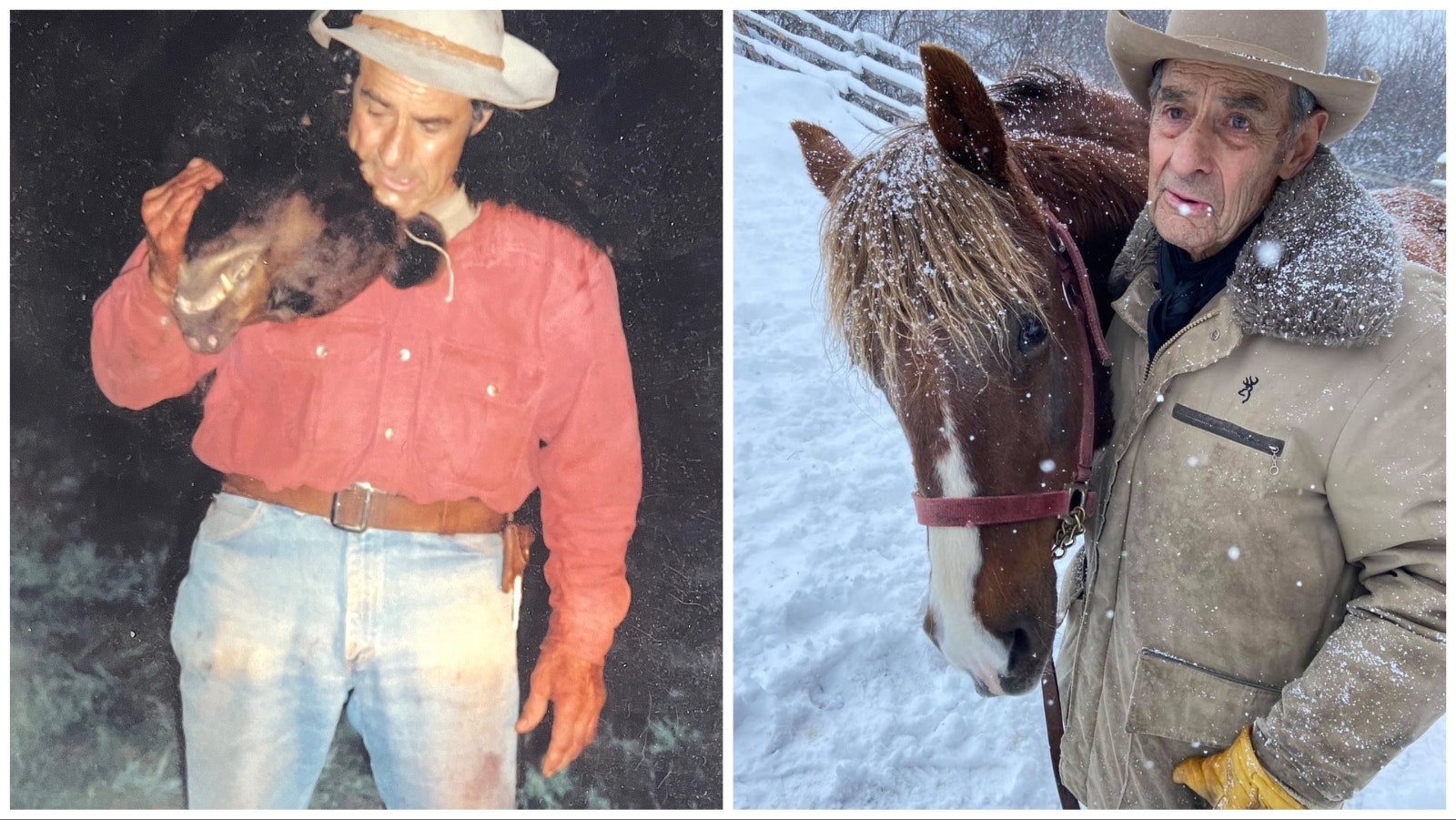

One particular encounter with a bear could have turned deadly. The massive bear was nicknamed Scarface for a nasty wound above its left eye. For years, Pucci pursued the wily bruin, but neither he nor his clients ever got a good shot off.

“We stalked and trailed him in all kinds of weather, dawn and dusk, but he got away every time. He learned to feed and travel only at night,” Pucci said. “That ol’ Scarface just kept on eating, hiding, and getting bigger and fatter. Making fools of us.”

Finally in spring 1983, with his hunters all gone, Gap set out for Scarface once and for all. Near dusk, he came upon the cagey adversary and got a good shot off from his pre-1964 .308-caliber Winchester. He heard the bullet thud into the bear’s side, but Scarface did not go down. He disappeared over a distant ridge.

“If the big bear was only wounded, I knew this could be a dangerous situation, especially in the dark with rain and snow soaking me through my rain gear, making it hard to move very quickly,” Pucci said. “Big bears don’t always immediately drop even when mortally wounded. Bears can take a lot of punishment, even with a heart and lung shot, they can go a long way before lying down.”

Pucci set his rifle aside, stripped off his heavy poncho for better mobility and followed the bear’s tracks with a flashlight and his trusty .44 Magnum revolver. For two hours he tracked the wounded bear in the pitch black.

“Every stump looked like a bear,” Pucci remembered about cautiously making his way through the heavy timber.

“Then, all hell broke loose! There was a loud growl and teeth-chomping splitting the night air,” he recalled. “It happened so quick I could hardly comprehend what was going on. I felt something reach out and hit me hard in the calf of my left leg, just above my high snowpack boots.

“The blow knocked me flying into the air. I still remember my hat and flashlight flying off into the night. I rolled over at least twice, trying to regain my footing.

“Getting to my knees, I instinctively pointed the barrel in the direction of the now-moving bear at about 10 feet away. I cocked the hammer and fired. A loud explosion rocked my arm. Two feet of fire came out of the barrel, lighting up the dark night.”

To find out how that encounter turned out you’ll have to buy the book, Pucci says.

“It gets my bristles up when people question whether my dad really did everything he claims,” daughter Teresa Pucci-Haas said. “These are real fact stories. I was there. I lived them with him.”

Off-grid With The Wilderness Family

Pucci’s hunt camps were in the middle of nowhere. Small clearings nested within a tangle of dark, thick woods few have ever penetrated. No hospital if someone were injured. No convenience store for a snack. No modern amenities whatsoever.

These are places so remote that Gap found out he was a first-time father only when a bush plane flew over low at hunt camp and dropped him a note.

Scrawled on yellow legal pad paper, it read: “Gap, you are the proud papa of a baby girl, 7#, born on Friday, 10-13-78. Mother and daughter are doing fine.”

Catherine was born first. Teresa followed two years later, also in October. The girls took to off-grid living with aplomb. They knew no other way.

“They would play Outfitter Barbie, attaching dolls to toy horses with rubber bands and head them off into the forest for an elk hunt,” Pucci said. “They grew up with the unspoiled Wyoming wilderness for a backyard. They would pull themselves up on the backs of our more patient Morgan horses when they were 3 years old and ride around the property.”

The girls’ babysitter was a German shepherd named Nino. Their closest friends were animals. The whole family were rugged individualists to the core.

“Wild animals were the first sights the girls saw as we held them up to the windows of the small log cabin. Our ranch horses and other animals would look right back into those windows, watching the little girls grow up,” Pucci remembered.

Catherine and Teresa played outside all day with any animal that could be suckered into it — including wild ones.

“The girls had no human playmates, so they played together with any animal that would play with them,” Pucci said. “I remember they played with a certain coyote who would run up and down the fence line as if to show off his speed. Their favorite playmate was a bighorn ram they named Amigo. They would run around the haystack chasing each other in a game of hide-and-seek.”

They Pucci family clan didn’t so much shun society, they just didn’t live anywhere near it.

Gap was gone from home much of the time, though. Up to eight months a year he would be out in the wilds hunting something, helping clients fill their tags.

“By the time they were about 7 I would bring one of the girls with me to camp for a 10-day hunt,” Pucci said. “The other would stay home and help mom. Then we would switch girls for the next hunt. They would do chores around camp just like my hired hands.”

Retired And Reclusive

After his retirement in 2008, looking back, Pucci is quick to credit his hardworking mounts for the success of his business and his very life. He favored the Morgan breed almost exclusively for their smarts and endurance.

“They built my business and paid the bills. They were my friends. I learned to have more patience with my horses than I ever had with most humans,” Pucci said. “Horses saved my life more than once, and I learned to know and respect them. If treated well, they’ll give their life for you, especially in desperate situations.”

Pucci figures he rode about 1,000 miles a year horseback. He feels it these days in the hips. They’re shot. So are his shoulders. Recent heart scares and a bout with COVID-19 slowed the ol’ cowboy down as well, but he still completes his daily chores on the ranch.

A once majestic horse herd is now down to the last stallion, a mare and a gelding. The goats are gone, the chickens killed off by foxes and coyotes. The last dog he’ll ever own — Nina, another German shepherd — died last spring.

There are still about 20 or so peacocks on the property. They do surprisingly well in Wyoming, and Gap has always had them around to brighten up the place.

There is also a friendly badger Pucci calls Tuffy. He’s had to escort Tuffy out of the house more than once.

The lifelong devoted Catholic has become a bit of a St. Francis of Assisi in a way. His reverence for critters of all kinds runs deep.

Hungry elk, moose and sheep stop by almost every winter, and Pucci throws them what hay he can spare even if big game managers frown upon that sort of thing.

“I probably missed some ‘dos and don’ts’ somewhere in there,” Pucci said. “Look, I know these guys at Game and Fish are doing the best they can. But they have more book smarts than actual experience.

“I lived in [close harmony] with wildlife for 50-some-odd years. I've tracked them, killed them, studied them and rescued them. I know a thing or two about wildlife.”

In his living room, Pucci is surrounded by trophy mounts, his life’s work on display courtesy of skilled taxidermists.

Bear, elk, moose, deer, sheep and several ducks keep the timeworn hunter company. A coyote with a snowshoe hare in its mouth stands by the fireplace. A pine martin with an ermine in its mouth tells a story of revenge. Pucci trapped that ermine after it had killed one of his chickens.

The outfitter doesn’t have the heart to raise a rifle at an animal anymore. He’s come to view wildlife as worthy adversaries and one of God’s gifts to mankind.

The other day, a coyote let out a high-pitched howl from just outside the chicken coop where Pucci’s peacocks are boarded.

“I came out and he slunk away, almost looking guilty that he was caught snooping around,” Pucci said. “I called out, ‘Go on, git! I ain’t gonna shoot ya.’”

Every day is a blessing at this point, Pucci said. He adds that he is grateful he came out West just in time to meet and learn from some of the last of the great cowboys.

“I've lived a good life. Wish I could do it all over again,” Pucci said. “I will, in Heaven, with all the good horses I ever rode.”

Jake Nichols can be reached at Jake@CowboyStateDaily.com

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.