Wyoming’s efforts to delist grizzly bears – possibly within the next year – could be derailed by poor predator management plans in Montana and Idaho, a bear expert tells Cowboy State Daily.

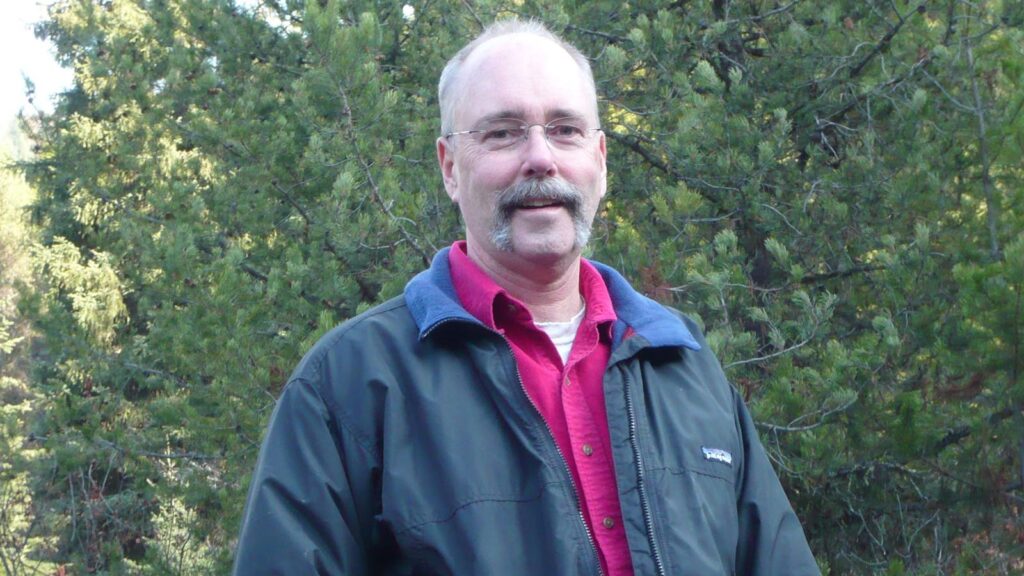

For instance, Montana has been offering a bounty on wolves, said Missoula, Montana, wildlife biologist Chris Servheen.

“You don’t even have to actually kill a wolf to collect. You just have to say you went out and tried to kill a wolf,” he said. “That’s like going back to the 1800s. That’s the dark ages of wildlife management.”

And it’s why Servheen said he recently testified for members of Congress that grizzlies shouldn’t be delisted – at least not now.

Wyoming Game and Fish Director Brian Nesvik, who Servheen said he knows well and admires, testified at the same congressional subcommittee hearing in favor of delisting.

Not Against The Idea Of Delisting

When it comes to grizzlies, Servheen speaks with considerable authority. He was the grizzly bear recovery coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for 35 years prior to his retirement in 2016. He’s now the board chair and president of the Montana Wildlife Federation.

In principle, he’s not against delisting grizzlies.

“I was the main proponent of delisting for years,” he said. “I wrote the first delisting rule and defended it in court.”

So, what changed his mind?

Overall terrible state-level predator management, particularly in Montana and Idaho, he said.

Those states handle their wildlife largely based on “anti-predator paranoia” rather than sound wildlife management, Servheen said.

Bad Wolf Policy Could Affect Grizzlies

Though the bulk of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and its estimated 1,000 grizzlies are in Wyoming, parts of it are in Montana and Idaho. There’s also a large population of grizzlies in northwest Montana, centered around Glacier National Park, and federal delisting would affect them as well.

Montana allows setting neck snare strangulation traps for wolves, hunting wolves at night with artificial light and night vision scopes, as well as hunting black bears with packs of hounds, Servheen said.

At least within the “trophy game zone” immediately adjacent to Yellowstone Park, where the core population of wolves is, Wyoming doesn’t allow those wolf hunting practices. Wolf hunting is allowed there only by licensed hunters during designated hunting season and within bag limits.

In the rest of Wyoming, or 85% of the state, wolves are in the “predator zone” and can be killed at any time without bag limits.

Wyoming also allows using hounds to hunt mountain lions, but not black bears.

Heavy-handed and “unnecessary” wolf killing policies such as Montana’s can affect grizzlies, Servheen said.

For instance, snares set for wolves sometimes kill grizzlies, and it isn’t known how many.

“There’s little to no incentive for the people who are doing these things to report them (grizzly snare trap deaths),” he said. “Or the bear might get caught in the snare and go off and die somewhere else, so nobody might realize it even happened.”

And when hounds are set loose after black bears, they will sometimes go after grizzlies insted, he said, because the dogs don’t know the difference. That has led to some grizzlies getting killed.

“The hound hunter might encounter a grizzly fighting the hounds, or a grizzly that has become agitated trying to flee the hounds, and that’s a situation in which grizzlies can be killed,” he said.

Isn’t Just About Numbers

During his testimony for the congressional subcommittee, Nesvik said that the population of grizzlies in the Greater Yellowstone is roughly double the target number supposedly needed for delisting.

However, delisting is about more than just numbers, Servheen said.

“You have to have proper (state) regulations in place” and at least in Idaho and Montana, that’s not the case right now.

There also has to be adequate habitat protection, he said.

Without all three of those things – an adequate number of bears, habitat preservation and proper state regulations that will prevent overkill once Endangered Species protection is removed – delisting won’t work in the long run, he said.

And even if Wyoming has sound policies, delisting won’t work for one state alone, Servheen added, because the ecosystem and bear population are singular units that don’t recognize state lines.

“We’ve come a long way and the bears are doing well,” Servheen said. “But they aren’t going to be if this anti-predator paranoia continues. State legislation is focuses on how many wolves and bears they can kill.”

Unfounded Fears Could Hurt Hunting

The greatest fears associated with wolves and grizzlies – that they’ll attack livestock and ruin big game herds – are largely unfounded, Servheen said.

“When we look at the overall numbers of deer and elk, and the rates of hunter success, there’s not a problem related to predators,” he said.

And while certain cases of wolves or bears killing livestock garner attention, in the larger picture that’s not a problem either, he said.

“We don’t want wolves to kill livestock, and there are mechanisms in place to deal with that,” he said.

Overall, the numbers of livestock killed by wolves and bears don’t add up to much, Servheen argued in a 2022 story he wrote for Wildlife Professional magazine.

For instance, between 2018 and 2020, roughly 113 cattle and sheep were lost to wolves each year, or 0.00428% of the cattle and sheep in one Western state, he wrote in the article.

However, during 2015 alone, 40,000 cattle and sheep were killed by the weather in Idaho, Servheen stated.

Overly aggressive killing of predators also is bad for the public image of hunting, he added. That’s important, because if anti-hunting sentiment takes hold with most Americans, hunters could be overwhelmed.

“If you’re shooting wolves at night over bait with night vision scopes, it erodes the image of hunting in the eyes of the public,” he said. “Less than 3% of the American public hunts, and even fewer than that hunts big game.”