There’s no difference between free speech and hate speech under Wyoming or federal law.

As abhorrent as racist, bigoted, homophobic or sexist comments may be to some people, the law and First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution dictate that no crime has been committed until a credible threat or act of physical violence has been made.

Determining what’s a credible threat can also be a highly emotional debate, and navigating what to do when hate speech is heard or seen is also complicated.

Often difficult in today’s political climate is maneuvering between what may seem offensive or even violent to some and a simple expression of opinion to others.

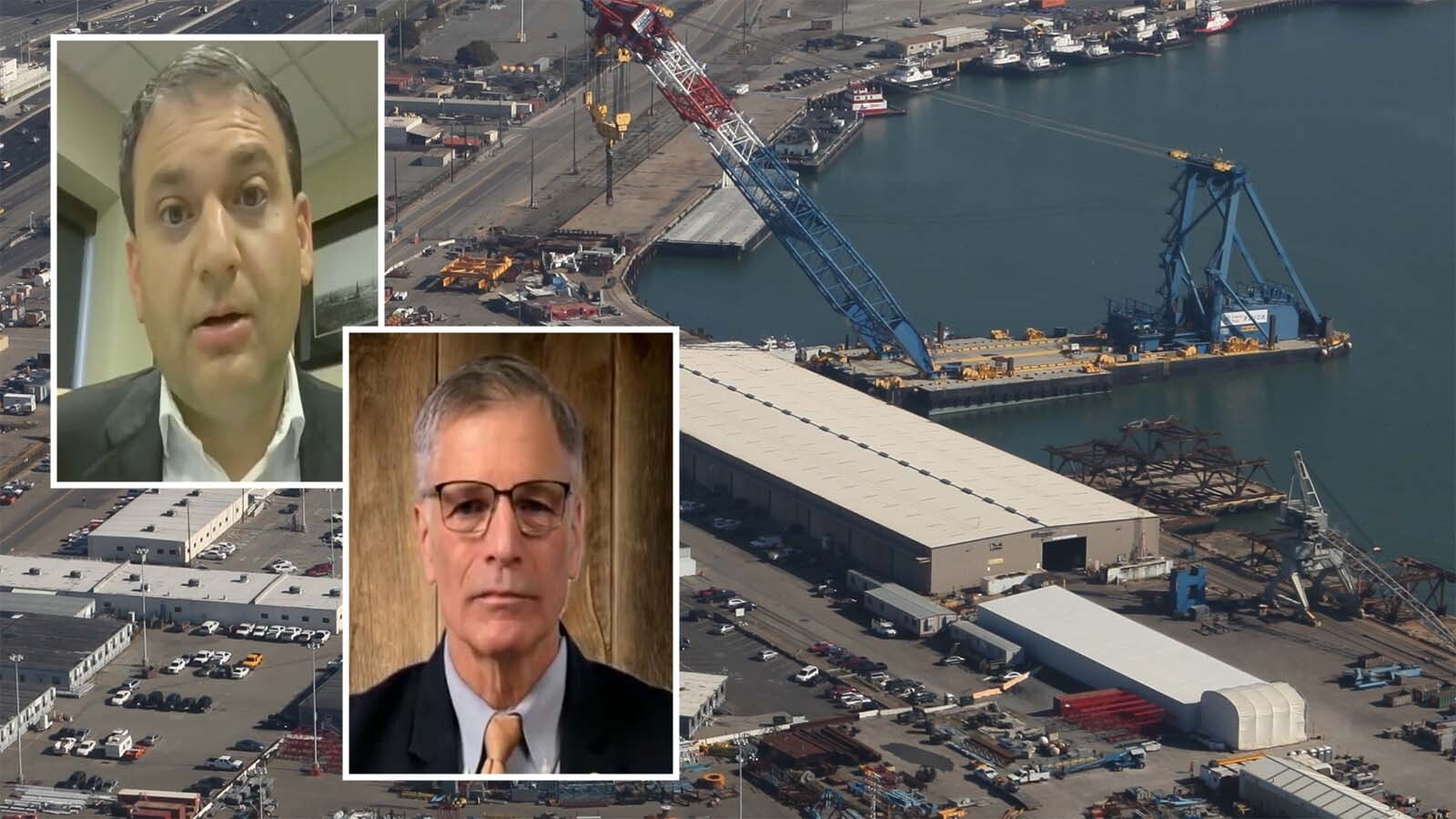

“We can’t be cavalier about prosecuting these acts,” Wyoming Acting U.S. Attorney Eric Heimann told Cowboy State Daily. “Government is not in the business of mandating people’s free speech and I don’t think the people want us to be.”

The big problem, Heimann said, is most people who commit hate crimes voiced hate speech before they did their acts. On the flip side, most people who use hate speech don’t escalate to committing heinous attacks, acts of violence or credible threats.

On Monday, Heimann and the U.S. Attorney’s office held a presentation in Cheyenne on identifying and reporting acts of hate for United Against Hate Week. During the presentation, “Repairing the World: Stories from the Tree of Life,” was shown, a documentary on the 2018 Pittsburgh synagogue shooting that left 11 dead.

The shooter in that event had issued many hateful comments online about Jewish people and minorities online prior to the attack.

This event hit home for Mt. Sinai Synagogue in Cheyenne, which arranges a police presence outside its facility for all of its worship events and installed surveillance cameras after the incident at the Tree of Life Synagogue.

“We don’t want to be the next Tree of Life,” said Jason Bloomberg, a member of Mt. Sinai. “That’s what your Jewish neighbors are dealing with in Cheyenne.”

In Cheyenne, Laramie County Sheriff Brian Kozak said he hasn’t seen any noticeable presence of hate crimes, and Heimann admitted his office didn’t prosecute any hate incidents last year.

“It’s always a concern for us, we just haven’t seen any incidents,” Kozak said.

Modern Speech

With technology and social media, hateful speech is easier to spew and spread.

It also occasionally shows up physically in Wyoming towns

A Wyoming white supremacist group recently put up “Keep Wyoming White” and other antisemitic stickers around the state in cities like Casper and Rock Springs.

In 2022, antisemitic literature was put on Cheyenne Republican state Rep. Jared Olsen’s lawn. Olsen is Christian but of Jewish heritage.

Last year, the city of Gillette implemented a hate crime ordinance. In that community, a lesbian couple that owns a pizza restaurant has been repeatedly harassed, the victims of homosexual slurs carved into one of their dining tables and their men's restroom covered in feces that had been spelled out in slurs.

Heimann said free speech doesn’t become a crime until it's specifically targeted at an individual in a threatening way, such as drawing Nazi swastikas on a Jewish person’s driveway without permission.

Something like this would likely rise to the level of a hate incident rather than a hate crime, he said.

In 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that free speech does not protect people who recklessly disregard a substantial risk that their statements could be viewed as threatening violence.

Heimann said people should pay more attention to expressions of violence online rather than specific ideology.

“Free speech does not give the right to say ‘fire’ in a crowded theater,” Heimann said.

Wyoming is one of of the last states without a hate crime law on the books, but Heimann noted that a hate crime often involves an underlying crime to begin with, that could be fueled by a wide range of factors that include negative bias against race, skin color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, or disability.

Many believe the brutal 1998 murder of Matthew Shepard, a gay University of Wyoming student, was a hate crime fueled by Shepard’s sexual orientation. Shepard’s killing sparked a national movement that ultimately led to the passage of a 2009 federal law leveled specifically against hate crimes.

Despite some who believe otherwise, Heimann pointed out that white people can also be victims of racially-charged hate crimes, mentioning an instance in Hawaii in 2014 where two native Hawaiians beat up a white man because of his race and were convicted for committing a hate crime.

“Thankfully, it’s not protecting only specific groups of people,” Heimann said. “It’s not specific to a race.”

Also not tolerated under federal law is discrimination for services, such as refusing to provide a disabled person access to a building, refusing to rent a home to a family because of the color of their skin, or turning away someone from voting because of their race.

Call It Out

The biggest solution to hate speech, Heimann said, is calling it out and reporting it.

That’s what Rock Springs Mayor Max Mickelson did in an official statement in response to the white supremacist stickers and other rhetoric that recently popped up in his community from the white nationalist group Patriot Front.

“In my position, I wanted to be very clear, while we will not interfere with core political speech, that does not mean extremism, bigotry, racism, etc. are welcome in our city,” Mickelson said. “While we will protect citizens' First Amendment rights, we will use our voice to denounce any speech that incites division and tribalism. We are Americans first, then Wyomingites, and, at our core, we are the neighbors who make up our city of Rock Springs.”

Mickelson also said instigating criminal acts is still a crime and will always be enforced without distinction for underlying political philosophy.

Heimann encourages the public to reach out to his office and report acts of hate speech to the FBI and his office so they at least have it on their radar, even if it’s not something that’s prosecutable or seen as a threat to other people.

“I’d love to tell someone that something can be done every time, a lot of times that isn’t the case,” Heimann said.

Cheyenne resident Noam Mantaka, who runs an Israeli food truck, has personally received anti semitic comments at his business over the last few months. In both of the two incidents where it happened, bystanders stood by and said nothing while the offensive remarks were made directly to his face.

Mantaka said he was still encouraged by the fact those bystanders came up to him after and expressed their condolences for what happened.

Leo Wolfson can be reached at leo@cowboystatedaily.com.