There was a time prior to 1960 when almost nothing was known about a bug called Naegleria fowleri. The microscopic single-cell organism is one of about two dozen species of Naegleria that can be found in warm freshwater and soil.

N. fowleri is the only one that kills. With stunning effectiveness. In nearly 97% to 99% of known cases, the victim is dead within five days of the onset of symptoms.

Known as the “brain-eating amoeba,” Naegleria fowleri makes its way into the nasal cavity and up the olfactory nerves until it reaches the frontal lobe, where it immediately starts devouring brain tissue.

It is the causative agent of primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), a rapidly fatal infection of the central nervous system that is rare but extremely deadly.

The discovery of the brain-eating amoeba in three Grand Teton National Park hot springs was “not a huge shock,” according to the scientist that made the finding, but detecting it in all three now when tests in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s turned up nothing, was an eye-opener and cause for some level of alarm.

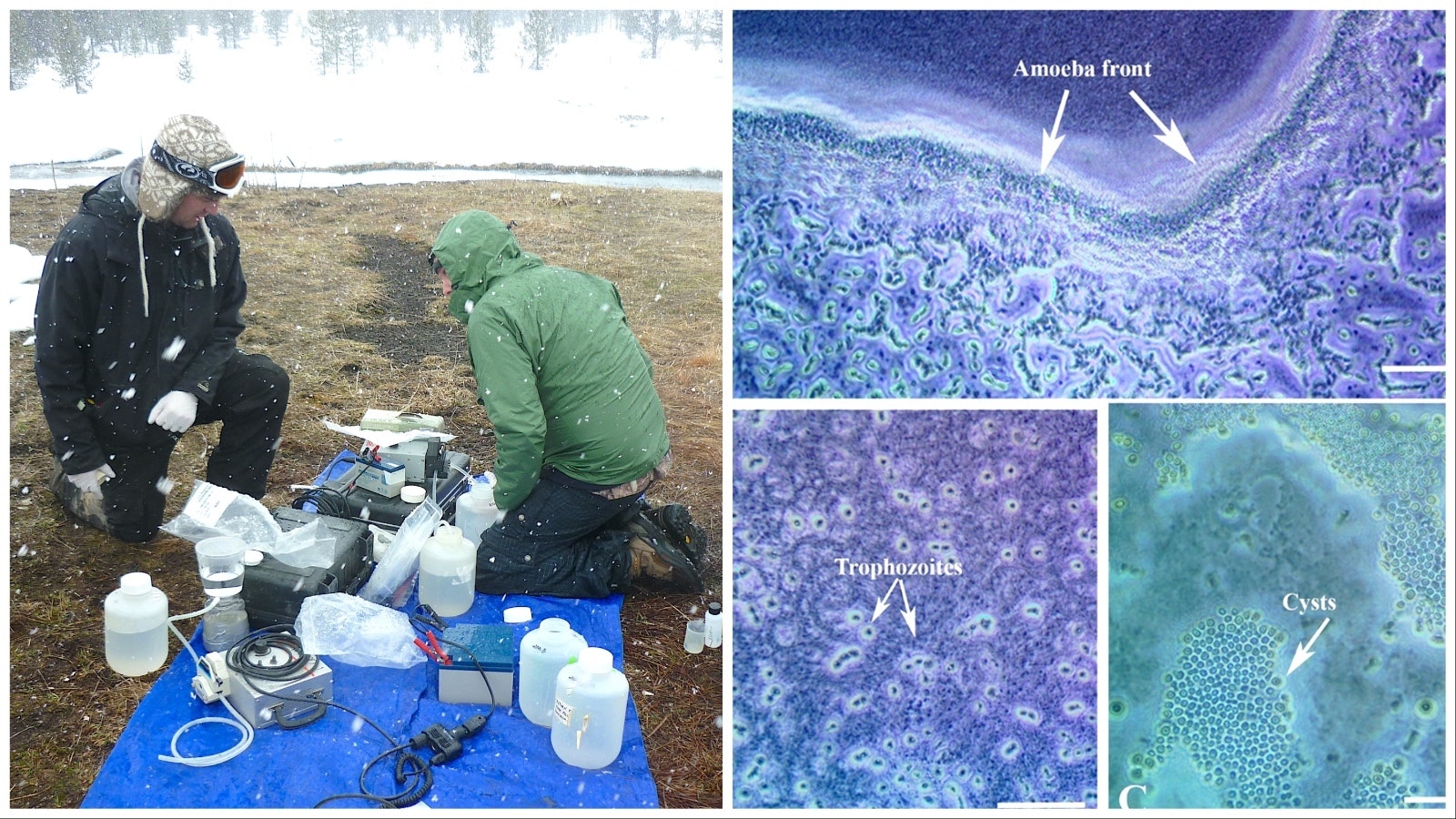

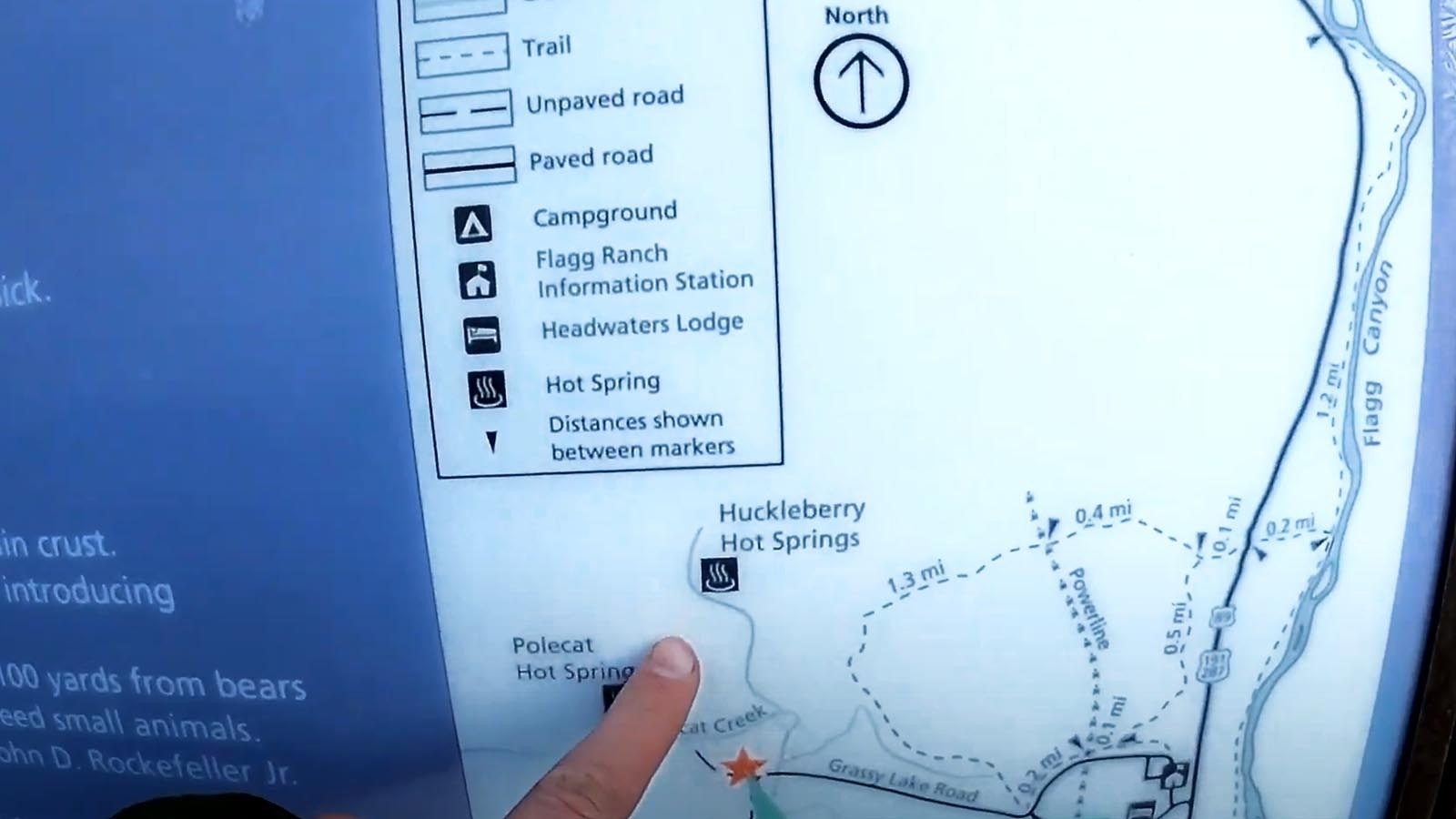

As soon as Elliott Barnhart and his team confirmed they had detected N. Fowleri in popular soak spots Huckleberry Hot Springs, Polecat Springs and Kelly Warm Spring during a three-season study in 2016, then-supervisor of Grand Teton David Vela issued a press release advising against swimming in the infected waters.

When the resulting research paper was finally published just last month, it prompted yet another wave of warnings about the dangers of “hot potting” in Grand Teton.

But just how unsafe is it to soak in hot springs? Cowboy State Daily asked Barnhart, the USGS microbiologist and lead author of the research paper, what he thought — and more pointedly, whether he would let his own kids swim in them.

Deadly Parasite

Statistically speaking, death by PAM is far, far lower than other already unlikely scenarios like shark attack (five annually). You are way more likely to die from a fair carnival ride breaking down (four annually) or a coconut falling on your head (150 people a year).

Worldwide, from 1937-2018, there have been 381 confirmed cases of PAM and just seven survivors. Only four people survived out of 157 known infected individuals in the United States from 1962 to 2022. Three cases were reported in the U.S. in 2022 — Iowa, Nebraska and Arizona — according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The parasite causing amoebic meningoencephalitis has been found on every continent except Antarctica. It has a higher prevalence of cases in poorer countries, most notably Pakistan and Mexico, but has been identified in 33 nations, with the majority of the cases being in the U.S.

The CDC states ritual ablution such as wudu is a potential risk factor in contracting PAM in predominantly Muslim communities like those of Pakistan where it is a common practice to cleanse the basal passages with water. It would account for the current outbreak of PAM in that nation.

N. Fowleri is typically found in warm freshwater bodies such as ponds, lakes, rivers, canals, ditches, hot springs and under-chlorinated swimming pools.

The parasite has been found in drinking water supplies, garden hoses, waterparks and other areas of concern. Laboratory-confirmed PAM case-patients in the United States are most often young males (79%), especially those 14 years old and younger.

The reasons for this aren't clear. It is possible that young boys are more likely than others to participate in recreational activities like diving into water and playing in sediment at the bottom of lakes and rivers.

In the United States, most PAM cases have historically been contracted in warm, southern states like Texas, Arizona, Florida, South Carolina and California. More recently, cases have also popped up in Iowa, Nebraska, Indiana, Maryland and, most notably, Minnesota.

The “migration” northward is most a result of climate change, some scientists claim. When positive samples were collected from a Minnesota lake in August 2010, Minneapolis was experiencing its third warmest August on record (from 1891-2023).

“The Minnesota case underscores the northern geographical expansion of PAM cases and the need to better understand conditions in northern latitudes under which N. fowleri persists and can threaten human health,” states the report’s authors.

Whether global warming or simply more and better testing, cases are on the rise slightly — up 1.6% on average each year from 1965 to 2016 — and they are showing up in more northern states in the U.S. like Indiana and Minnesota.

‘Not A Huge Shock’ It’s In Wyoming

“While I did not expect to find it in Grand Teton — others had looked in these same hot springs and not found it — it was not a huge shock. I know they did find it in Yellowstone, in the Boiling River. I knew there was a chance,” Barnhart said.

The warm-loving amoeba thrives in water between 75-100 degrees Fahrenheit. It has been found in water as cold as 50 degrees and as warm as 115. Lab testing showed the amoeba can exist for only a short amount of time above 118 degrees.

Thermal activity was thought to be the only way the brain-eating amoeba was going to be found in usually frigid waters in Grand Teton NP.

“What does Naegleria fowleri tell us? These cases in Minnesota, maybe one now in Nevada, it seems cases are becoming more prevalent further north,” Barnhart said.

“We are doing studies [in Wyoming] to understand where it is and what causes it to grow in these areas. We are still learning what causes it to show up in some areas and not in others.”

Scientists are still learning a lot of things about N. Fowleri.

What We Know

South Australia in the 1960s was ground zero for the infection, though we now know the bug itself was around before that.

People began getting infected in several towns served by above-ground water pipelines in Australia. The meningoencephalitis cases were traced back to N. fowleri, which was first discovered by Malcolm Fowler, an Australian pathologist at Adelaide Children's Hospital.

Once scientists knew what they were dealing with and began chlorinating the drinking water, there has not been another case in South Australia since 1981.

A 1966 report was the first to identify infections in the United States, which occurred in 1962 in Florida. Later investigations using archived autopsy tissue samples identified PAM infections in Virginia as early as 1937.

Again, to reiterate, the offending parasite is only interested in brains and can only get there from the nasal cavity. Studies suggest water would have to be forced up the nose, but a splash might do it. In cases of contaminated drinking water being behind PAM, it is always because the water was used to flush out sinuses or had somehow been breathed in through the nose.

Lab coats are still uncertain as to what exactly N. fowleri eats in situ. As a free-living protist, the amoeba mostly consumes bacteria, along with yeast, algae and other microorganisms. N. fowleri forms a sucker-like food cup to feed on bacteria or brain tissue.

“Food source is also an active area of research. We are studying what this organism is eating. For instance, a bacterium you do see a lot of in hot springs is the Thermus species,” Barnhart said.

The discovery of a cyanobacteria called Thermus aquaticus was one instance of a gamechanger. Found in a Yellowstone hot spring, the bacteria defies all preconceived notions the organism cannot tolerate high temperatures. This one actually prefers water above 158 degrees.

Finding Naegleria

“The first thing we did is something I do a lot of, and that is analyze DNA in the water. We were able to extract DNA out of a water sample. Similar to, say, Ancestry.com, we compare samples to a database and can say, ‘Oh look, we detected fowleri,’” Barnhart said. “Then we took it a step further, which is to grow the pathogen in a Class 2 facility.”

Barnhart has conducted numerous field studies in rivers as well as subsurface coal beds and shale beds. He also helped install robots to study water in the Jackson, Wyoming, area through the Monterey Bay Institute supported by the Teton Conservation District.

There are about 100 protected and managed hot springs within Grand Teton National Park and the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway.

“In consultation with park scientists, they thought [Huckleberry, Polecat and Kelly pools] were ones that could be a good spot to find fowleri,” Barnhart said.

Soaking in Huckleberry and Polecat has been a longstanding tradition for locals for decades. Soaking in direct, so-called H1 geothermic waters like Huckleberry is banned by the park, but many bathers use outflow pools or simply ignore the directive. Kelly Warm Springs is open to the public for use.

“Soaking in H1 and P1 is prohibited in GRTE due to hazards associated with geothermal water being the sole source of recharge, but visitor use was observed during most sampling events,” the report says.

Barnhart said Polecat had the “most detections,” but it is difficult to quantify that data or what it might mean as far as risk factors.

“It’s hard to quantify. Just detecting it, especially in drinking water, would be an alarm,” Barnhart said.

4-Year-Old Was First US Death

The CDC states there is no established relationship between detection or concentration of Naegleria fowleri and risk of infection.

Barnhart credits senior research scientist Dr. Geoffrey Puzon from Australia for his input during the study. Puzon’s expertise is in detection and treatment in drinking water.

“He’s one of the world’s foremost experts on this pathogen,” Barnhart said.

The first known U.S. death of PAM from tap water happened in August 2013 when a 4-year-old child died of meningoencephalitis etiology in a Louisiana hospital after exposure to water used on a water slide.

Barnhart also added fowleri was detected in every body of water they tested — the aforementioned hot springs and two additional runoff pools.

“N. fowleri was detected more from sites with higher average temperatures although, overall, there were fewer real-time PCR detections in July when average temperatures were higher compared to November and March,” the study says.

Other research confirms N. fowleri is not always found at increased levels during summer months.

Learning more about the pathogen’s ecology and the conditions under which it can exist or thrive is of great interest to scientists.

Finding fowleri in Wyoming could suggest warming climate trends have facilitated a northern geographical expansion of PAM cases in the U.S., researchers say.

Or it could be the bug has always been here but just not discovered.

“Detection of N. fowleri in GRTE in this study but not in previous studies could be due to updated analytical methods or due to potential increased N. fowleri concentrations since previous studies were performed on the same hot springs more than 20 years ago,” the study indicates.

Survival: Human V. Amoeba

The deadly amoeba needs certain conditions to thrive, but it is adaptable enough to keep itself alive until its environment is most suitable.

Fowleri exists in three stages — cyst, trophozoite and flagellate. Trophozoite is the active, reproducing and feeding stage of N. fowleri. When faced with unfavorable conditions such as a scarcity of nutrients, trophozoites can temporarily transform into a nonfeeding flagellated stage. They can then revert back to the trophozoite form when favorable conditions return.

In addition, fowleri can live outside of water in soil in a cyst stage.

“The spore [cyst] form is very hardy. It can be transported like an egg by dust particles. When it gets to something it prefers, it can then turn into a trophozoite eating form,” Barnhart said.

And when it feeds on a human host, N. fowleri can be single-mindedly vile. The amoeba causes the body’s immune system to turn on itself as well as elicit a form of paralysis by secreting chemokines.

The signs and symptoms of PAM can be mistaken for other more common neuroinfections such as bacterial meningitis and viral encephalitis. But these other pathogenetic do not act nearly as quickly as PAM.

Symptoms occur within three to five days of exposure. They often include severe headache, fever and chills. Later symptoms can include photophobia, confusion, seizures, hallucinations and potential coma.

After the start of symptoms, the disease progresses rapidly and usually causes death within about five days.

A Few Survivors

Early detection can make a difference. In Florida, where the medical community is more familiar with the rare infection, a 16-year-old boy became one of four known survivors after contracting the deadly brain-eating amoeba from “cannon-balling in a stagnant pond.”

Once doctors at Florida Hospital for Children in Orlando figured out what they were dealing with, they placed Sebastian DeLeon in a medically induced coma and put him on miltefosine. The anti-parasitic drug is relatively new but has shown promise in successfully treating a few isolated cases of PAM.

Now 22 years old, DeLeon has made a miraculous full recovery after years of painstakingly relearning how to do nearly everything.

In 2013, Kali Hardig, 12, was infected with the parasite while swimming at a water park in Arkansas. Given miltefosine, Hardig spent 55 days in the hospital. She was eventually able to return home where she has since made a full recovery.

That same summer, an 8-year-old Texas boy also survived, although he suffered brain damage from what the CDC said was a delayed diagnosis.

The only other known survivor in the United States, who was not treated with miltefosine, was a patient in California in 1978.

Scientist Still A Soaker

When not in the field, Barnhart spends a lot of time staring at creepy crawly things under glass slides. Microscopic life in the laboratory can look positively monstrous at times. Barnhart tries to keep it all in perspective.

“I love hot springs, but I do look at them a little differently after doing this study,” Barnhart said. “I still soak in hot springs. I do keep my head above water and try to have my kids keep their heads above water and use nose plugs when we can.”

PAM is likely to become more prevalent in the coming years and something people in Wyoming may suddenly have to become aware of.

Barnhart and his colleagues continue their research in places like Lake Mead, Yellowstone and Grand Teton. With every study comes more knowledge.

Barnhart’s best advice for now?

“If you experience any symptoms after using a hot spring, seek medical attention,” he said.

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.