Being attacked by a grizzly bear, left for dead by comrades and then crawling for miles over the prairie while eating snakes and bugs is only one of many stories associated with legendary mountain man Hugh Glass.

Others tell how he was captured and forced into servitude by French pirates, spared by Pawnee Indians who had plans to burn him at the stake, and survived numerous other near-death experiences.

Historians have debated the validity of stories associated with Glass for years. What they have concluded is that by any measure, Glass lived an extraordinary life, and it may have been amplified by his own abilities as a storyteller.

Movie Magic

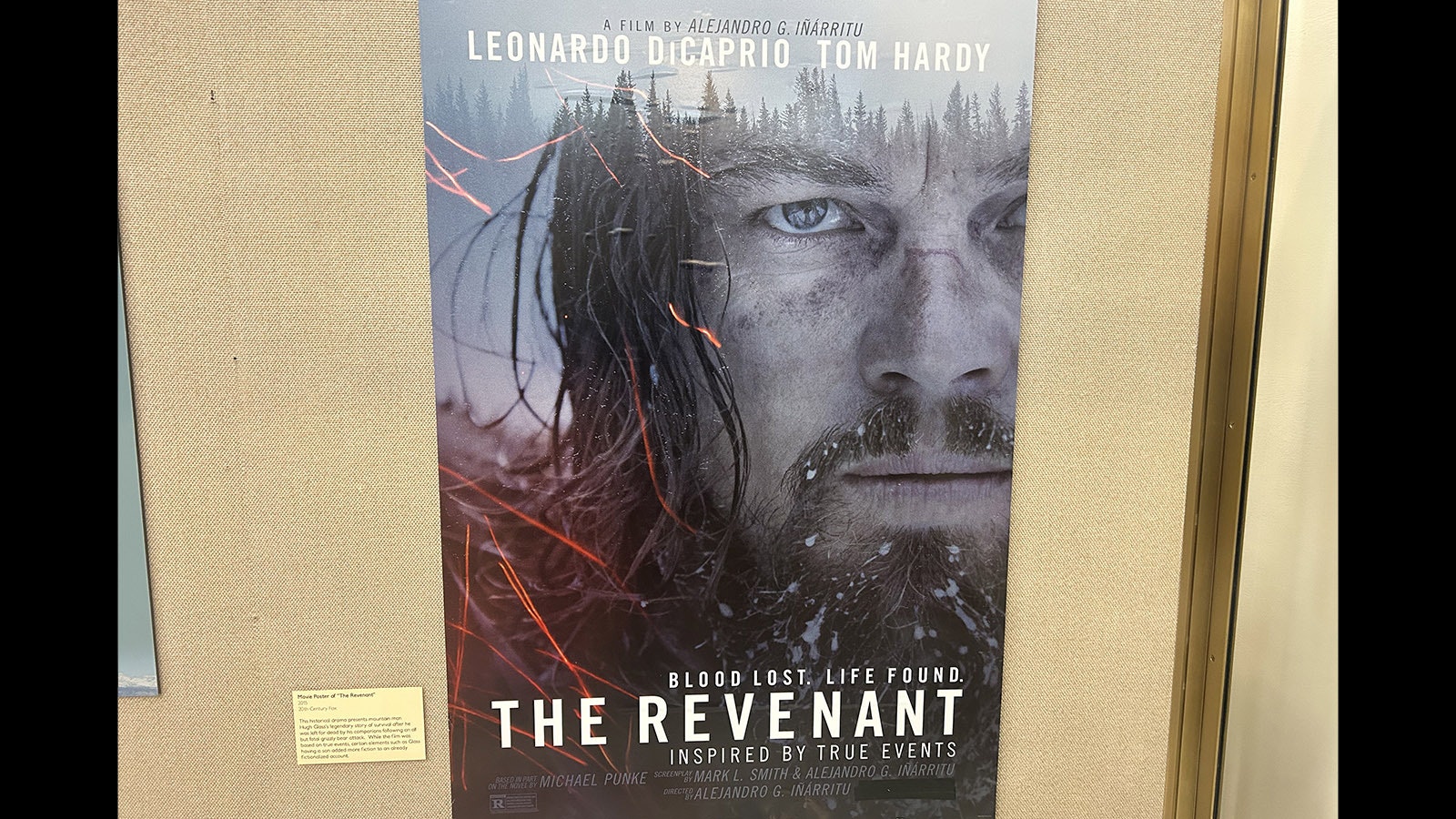

Rumor has it that a sequel to the 2015 film “The Revenant” starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Hugh Glass is in the works. Clint Gilchrist, executive director of the Museum of the Mountain Man in Pinedale, said he’s heard stirrings about another movie, but nothing firm.

Filmmakers consulted with Museum of the Mountain Man when they made “The Revenant,” and an exhibit in the museum shows Glass wielding a Bowie knife in a hand to claw encounter with a grizzly sow.

Gilchrist said although the many exploits associated with Glass prior to his traveling west in the early 1820s are unproven, much of what happened to him after the grizzly attack can be corroborated.

“The Revenant” received rave reviews from many film critics, but some historians objected because it didn’t follow the accepted research on Glass.

The movie is a fictionalized account inspired by the story of the Glass grizzly attack, his survival after the attack and his search for revenge on the two men who left him for dead — John Fitzgerald and possibly Jim Bridger.

There is significant speculation whether Bridger was one of the two men charged with caring for Glass after the grizzly attack. The main source who identified Bridger was Capt. Joseph LaBarge, and his comments were recorded 73 years after the mauling suffered by Glass.

Gilchrist said the film touches on many aspects of the history of the Rocky Mountain fur trade and provided an opportunity to celebrate a historic figure.

“You’ve got to remember, the filmmakers are in the entertainment business, not the history business,” he said.

The movie brought attention to the Hugh Glass story and gave the museum an opportunity to set the record straight, Gilchrist said.

“The movie did a really good job of bringing attention to the era of the mountain man,” Gilchrist said. “It’s hard to get that kind of exposure from millions of people. It did a real good job of portraying the look and feel of the times. Where they got it wrong was they changed the story.”

Larger Than Life

If half of what’s attributed to have happened to and done by Glass is true, it’s no wonder Hollywood made a movie based on his legend.

After being left for dead after the bear attack, yet surviving, Glass embarked on a career as a trader and trapper, which took him all over the West, including the Yellowstone territory. Of course, all adventure- and peril-filled. A battle with Shoshone braves reportedly left him with an arrow buried in his back, which he carried with him for hundreds of miles until he got to Taos, where it was dug out with a straight razor.

While there isn’t much known about what he did for several years after that, there are accounts of him attending the Bear Lake Rendezvous in 1928.

“Due to the monopoly and high prices being charged by Smith, Jackson and Sublette at this rendezvous, Glass was asked by the free trappers to represent them … and invite the American Fur Company to send a trade caravan to the 1829 rendezvous,” writes Clay Landry in a historical essay for hughglass.org.

An Exhibit

In response, the museum set up its Hugh Glass exhibit and published a history with references, maps and an in-depth account of where the fiction of the movie differs from the actual documented history.

The encounter between Glass and the grizzly sow happened in South Dakota and for several days after, Glass was barely alive but still breathing. Glass, not being able to travel, soon became a liability because hostile Indians were in the area.

The men charged with taking care of Glass abandoned him after five days and took his gun, knife and fire-making tools.

Over the next six weeks, Glass painstakingly covered the 250 miles between where the attack happened and Fort Kiowa on the Missouri River near present-day Chamberlain, South Dakota. According to the historical account, he ate bugs and snakes, and stole a dead bison calf from a pack of wolves during the night.

Late in the journey, he was able to secure a hide boat from Lakota Indians and floated the final few miles into Fort Kiowa.

By most historical accounts, Glass pardoned Bridger because Bridger was only 19 years old at the time. Glass never exacted revenge on Fitzgerald either, but he did get his rifle back, according to the historical research completed by the staff of the Museum of the Mountain Man.