CASPER — Here’s a riddle for those who slept in history class, continue to ignore museums and generally are not fascinated by the lives woven into the fabric of the West.

What two modern cities began as historic forts, are linked by a major highway and are named for a pioneering father and a son?

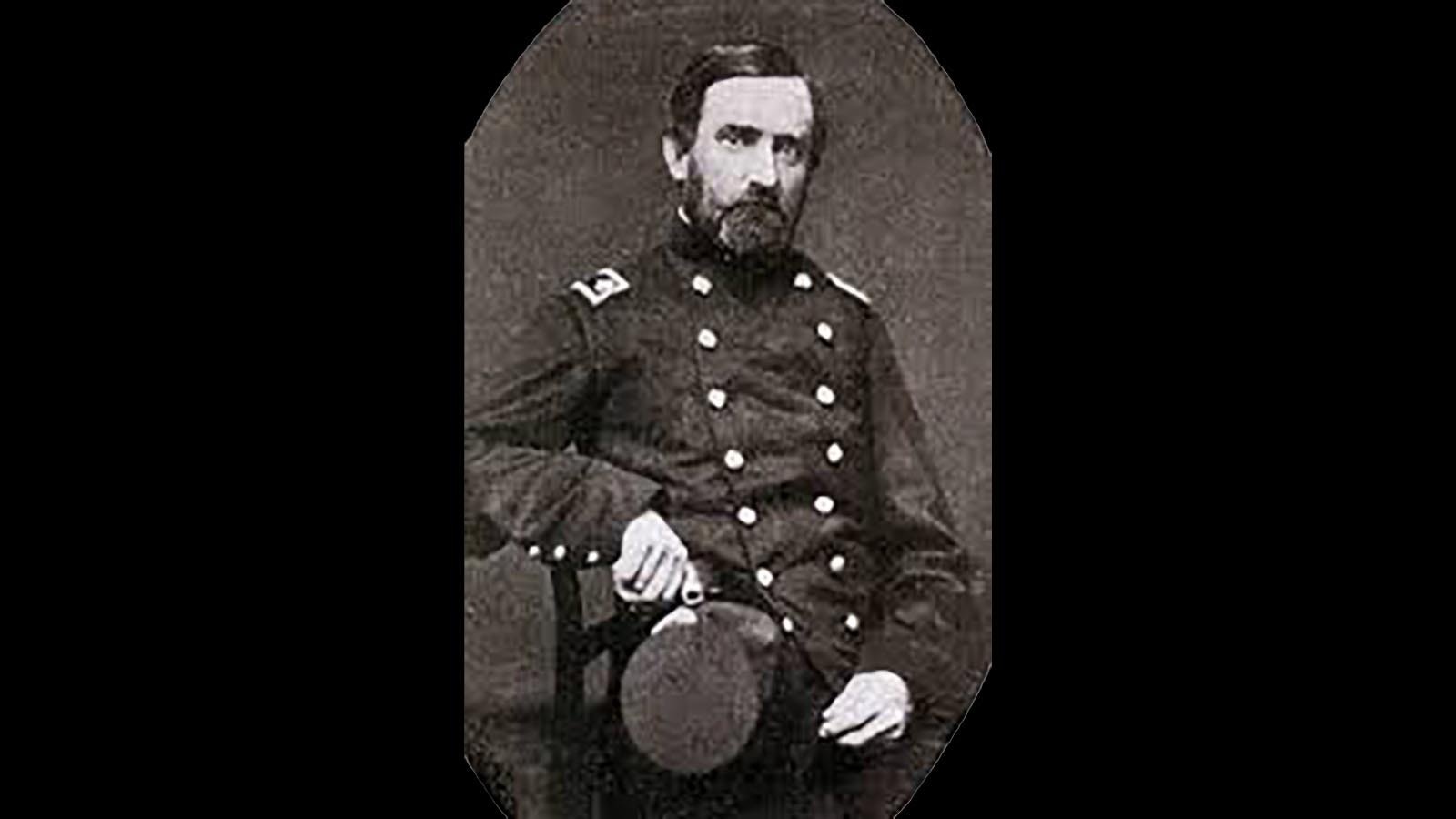

Finding the answer requires going back to the Civil War when a prominent attorney, who became president of a railroad and then member of the Ohio Senate was appointed to raise up a cavalry unit for him to command. The unit eventually became into the 6th Ohio Volunteer Calvary, later the 11th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry and was sent out west to the territory from the panhandle of Nebraska through Wyoming.

The mission? Well, it wasn’t specifically to protect homesteaders or fight hostile tribes.

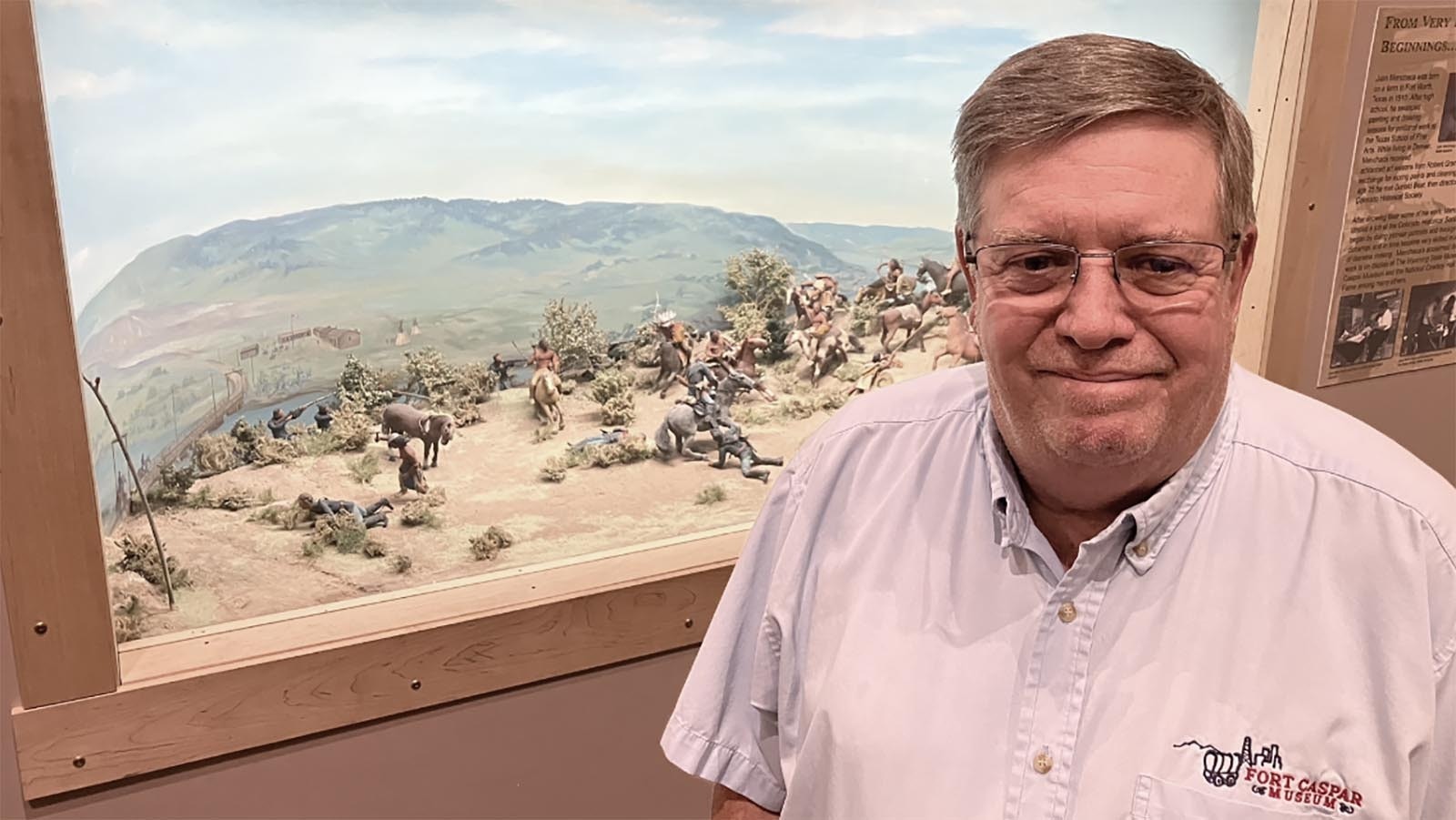

“They are not there to guard wagon trains,” said Fort Caspar Museum Director Rick Young. “They are there to take care of the telegraph lines. The government needs to know what is going on on the West Coast, that’s why they were out here.”

The legislator turned U.S. Army lieutenant colonel was named William O. Collins. And in his trek to the untamed West he brought his civilian 17-year-old son along in 1862. The son’s name was Caspar.

They couldn’t have known it at the time, but the assignment set in motion a series of events that would eventually lead to the naming of a pair of cities for father and son.

Union Gen. James Craig, who initiated sending troops west, ordered an outpost established on the Cache la Powder River in what became Colorado. It was named Camp Collins in honor of the lieutenant colonel whose bloodline can be traced back to the Mayflower.

During that first year, Lt. Col. Collins, based at Fort Laramie in what a few years later would become Wyoming Territory, his troops under him and Casper got their taste of the harsh winters, plentiful game and fishing in the region to the north, and the ways of the native people who frequently camped around the fort and the stations associated with it.

Caspar Collins, a talented artist, drew accurate depictions of native encampments, tribal people moving tepees with horses, and more. He is reported to have made friends with many of the Lakota people.

A New 2nd Lieutenant

Young said that in 1863, Lt. Col. Collins went back to Ohio to try and recruit more volunteers, and Caspar went with him. The now 18-year-old received his commission as a second lieutenant on June 30. He returned from his native state and was assigned oversight of the Sweetwater Station at Independence Rock.

Meanwhile, in June 1864, flooding overwhelmed Camp Collins in Colorado. A new location was needed, so Lt. Col. Collins approved a new site downriver that would be called “Fort Collins.”

While Lt. Col. Collins commanded Fort Laramie and the various stations, 3rd Colorado Cavalry Col. John Chivington on Nov. 29, 1864, led the infamous Sand Creek massacre of peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho women, children and older men — the most notable being Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle, who had struck a peace treaty and met months earlier with President Abraham Lincoln.

Native retaliation ensued. Cheyenne, Lakota and Arapaho warriors staged guerrilla retaliation raids resulting in the battles with Lt. Col. Collins’ troops at Mud Springs and Rush Creek in the Nebraska panhandle in early 1865. Caspar Collins took part.

“All of the hostilities in the summer of 1865 were because of Sand Creek,” Young said.

Father Leaves Son

In April 1865, the father left the son as he and other troop enlistments ended as the Civil War drew to a close.

“Some of the enlistment contracts were for three years, and some said, ‘Three years or the duration of the war,” Young explained. “Caspar enlisted later.”

In July, 2nd Lt. Collins was at Fort Laramie after a mission to find new horses for the Sweetwater Station. He sent troops back to the Sweetwater Station, and some speculate he remained there because he ordered a new uniform. Or maybe he just needed a break.

Gen. Patrick Connor also was there about to lead a campaign against the tribes and allegedly asked Collins why he was not back at Sweetwater.

Collins was said to have replied he did not want to ride back alone in hostile territory. The general then allegedly asked if he was a coward, to which Casper said he wasn’t. He joined troops escorting the mail from Fort Laramie to the Platte Bridge Station where the 11th Kansas unit was then in charge.

It was July 25, 1865, and thousands of warriors from the Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho nations were in the hills surrounding the station.

One of the warriors, George Bent, said there were around 1,100, Young said. An official U.S. Army report put the number at 3,000.

The End Comes

Members of the now 20-year-old’s unit arrived around 2 the next morning.

They reported passing a supply wagon train camped west of the station. The captain reportedly urged the sergeant in charge to go with them, but the sergeant said they needed to rest their mules. The captain from the 11th Ohio urged the major from the 11th Kansas to send an escort immediately. The Kansas commander did nothing until the morning.

Young said conflicting stories surround what happened next. One account has the officers of the 11th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry putting themselves on sick call.

“What we know is that there were no 11th Kansas officers theoretically available,” he said.

The Kansas unit’s commander assigned 2nd Lt. Collins to lead what became a 20-member troop escort. Caspar borrowed two pistols, a horse, left his cap with a friend as a token of remembrance should he die, and headed out of the station.

Shortly after, hundreds of native warriors left their hiding places and went on the attack. It was over quickly.

Casper Collins in one account behaved bravely, charging the attackers — and in one account tried to save one of his men by placing him on his horse.

Young said he spoke with members of the Pine Ridge Reservation who shared through oral history that Lakota warriors recognized Caspar and told him to go back, but his horse bolted and ran into the Cheyenne side of the attack.

His Body Recovered

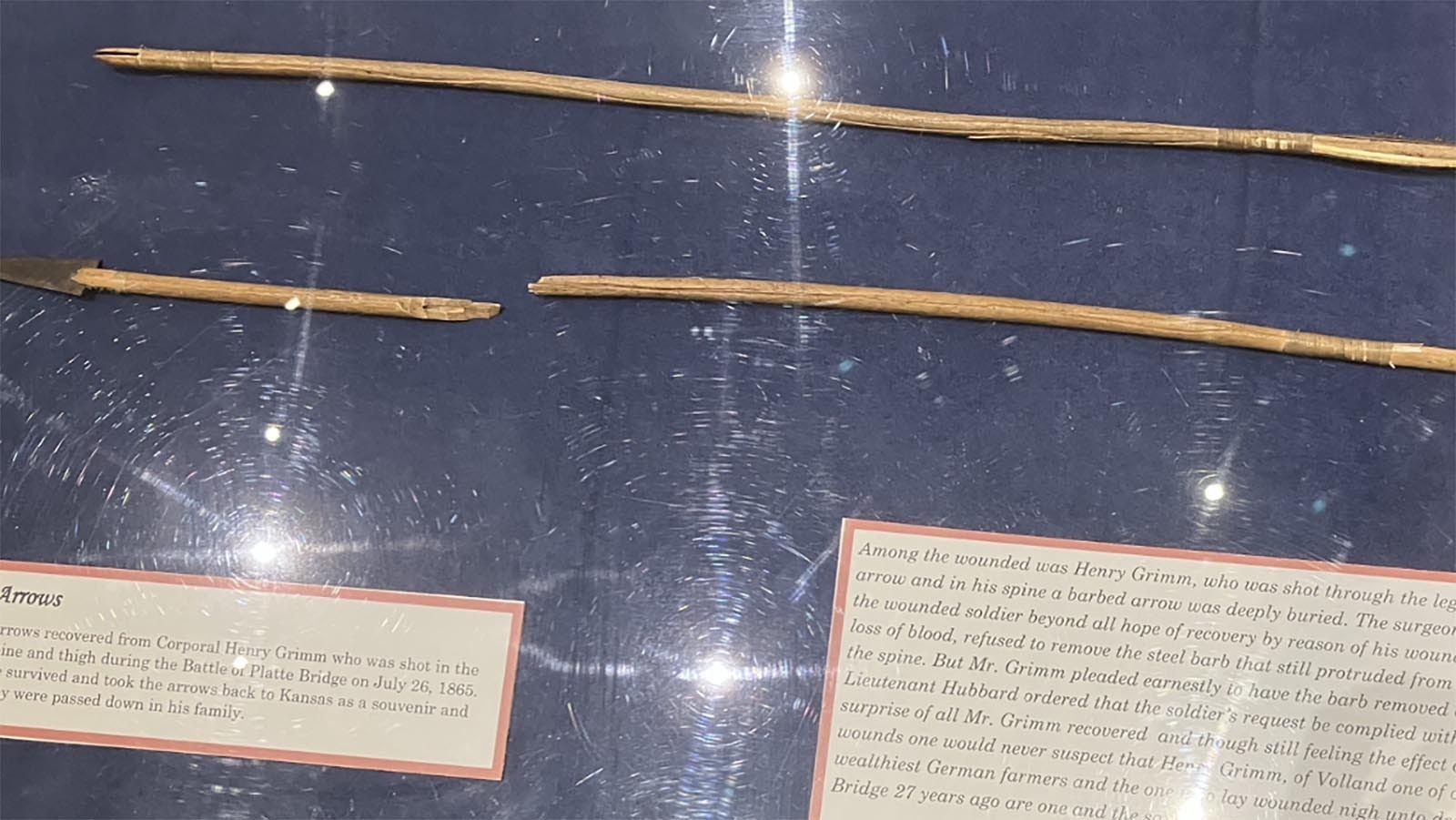

His body and the four others of the 11th Kansas were found the next day full of arrows and mutilated. The others had successfully retreated to the fort. One of those Kansas soldiers, Henry Grimm, had at least two arrows in his body, but lived. The arrows are now on display in the museum.

Caspar’s body was buried locally, but then disinterred in 1866 and sent to Fort Laramie for burial and months later disinterred and sent back to Ohio.

In September 1865, the North Platte Bridge station was renamed Fort Casper — because there was already a Fort Collins. The fort would be dismantled a few years later.

The official U.S. Army general orders renaming the station to a fort changed the “a” to an “e” as it tried to honor the fallen soldier. And in 1888, a city was born just south of the fort — Casper, with the same vowel change at the end.

The younger Collins died to get his name on a fort and then a city. The father was involved in the creation of Camp Collins, which became Fort Collins.

Does the father deserve to have a city named after him?

“He created the fort and set time there,” Young said. “So, yeah, first man here gets the town named after him.”

Other Cities Named For Fathers and Sons

How many other places in the nation are named for fathers and sons?

John Adams, the second U.S. president, influenced the naming of Adams, New York, Adamsburg, Pennsylvania, and Adamstown, Pennsylvania. John Quincy Adams, his son and the sixth president of the United States, has Quincy, Illinois, Quincy, Michigan, and Quincy, Washington, named for him.

(Note AP style now is to spell out the names of states, except in cutlines and headlines)

The great explorer and long hunter Daniel Boone has Boone, N.C., Boone Station, Ky., and Boonville, N.C., as memorials to his name. His son, Daniel Boone, a landowner, influenced the name for Danville, Missouri.

Now the cities of Casper, Wyoming, and Fort Collins, Colorado, are connected by 222 miles of Interstate 25. But there’s a deeper connection that began with a father and son from Ohio sent into the Wild West.

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.