JACKSON — Flying your own plane isn’t just for Fortune 500 CEOs. In fact, there’s an active community of Jackson underground pilots. They call themselves bush pilots and fly small aircraft that can cost as little as the average new car.

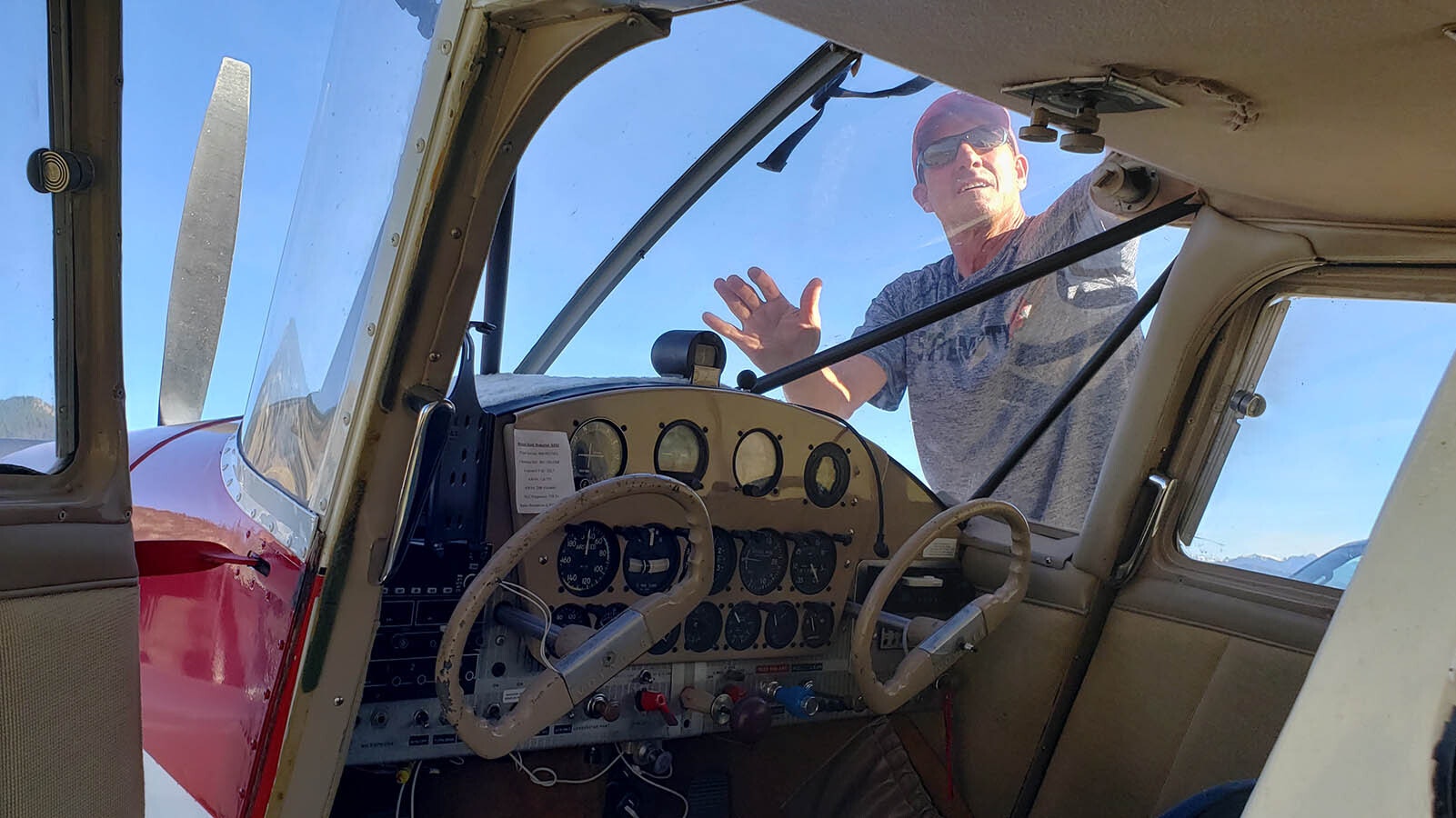

Scott Smith, “Smitty” to his friends, is one of these bush pilots. He flies a 1948 Stinson 108-3 voyager, a plane that he says cost him about $50,000.

“I have larger tires on it so it can absorb some of the rougher terrain needed to land in the back country,” Smith told Cowboy State Daily. “And I have a bigger engine in it and vortex generators on the wings to help the plane fly at a slower speed.”

Planes like the Stinson were originally designed for East and West Coast businessmen to visit their various locations.

“This was kind of designed to fly at a lower elevation,” Smith said. “But it comes with a little bit bigger engine in it. It has a 180-horse Franklin engine, so that’s a little bigger engine than normal in that aircraft.”

The vortex generators on the wings allow for a shorter takeoff and landing so the plane can land on short grass or dirt airstrips from 1,200 to 1,500 feet long.

It’s got fabric skin that’s been stretched over the body of the plane, then coated with a polymer referred to as “dope” that toughens the skin and makes it flightworthy.

Modern versions of that fabric can easily last 30 years with proper care, Smith said.

“Every airplane has to go through an annual inspection,” Smith added. “They’ll inspect the engine and the airframe and the integrity of the fabric.”

The Flying Bug

Smith caught the flying bug at a very young age. Growing up in Michigan, his parents’ home was in a poor area, where there was an abandoned grass airstrip.

“Growing up next to this airstrip that, you know, these planes would fly into, even though they weren’t supposed to be flying into it because it wasn’t really maintained,” he said. “I really was just kind of fascinated by flight.”

Anytime he saw planes landing there, Smith would race over to talk to the pilots about their airplanes. Eventually, one of them gave him a ride.

From that moment on, Smith knew he was going to fly. Some way, somehow — beg, borrow or steal — he would make it happen.

When the chance to buy part ownership of an ultralight plane presented itself when he was in his teens, he jumped on it.

“I think the whole thing cost $7,000 or something,” he said. “And none of the other partners wanted to fly it. They were kind of too scared to. It was funny. So, I ended up having (it). I was stupid enough more or less to just you know, fly it by trial and error.”

When he’d crash the plane — that happened a couple of times — he’d buy new parts, fix it up and take off again.

“My dad was principal of a school and his shop teacher was a pilot,” Smith said. “That’s the guy who got me into these ultralights, and then he kind of scared himself, he didn’t want to fly it anymore.”

So, Smith would call the shop instructor, who would explain how to do various things in the plane.

“I went on to get all the ratings, but I flew out of my backyard, which was just a house near an abandoned airstrip,” Smith said. “And so, I really would taxi out of my backyard down the road to this little airstrip, and then I would practice flying there.”

Fight Fire

When Smith came out to Jackson initially, he started fighting forest fires on a helicopter unit called a Helitack in 1992.

“We were the helicopter version of smokejumpers, except we rappelled into fires on 200-foot ropes,” he told Cowboy State Daily. “It was a really funny time in my world. And I just had such a lust for, I was so hungry for aviation.”

In the winter, he’d fly back to Key West in his ultralight plane, and then work on sailboats with his brother all winter.

The flight to Key West was over 2,000 miles and would generally take at least two days.

“Sometimes, depending on the wind, the cars would be going faster than I was,” Smith said.

But Smith would never trade in his plane for an automobile, even if he is slower up in the sky.

“I just really like the challenge of flying,” he said. “There are so many different levels of skill that you need, from talking on the radio, researching the weather and then the mechanics, you know, of flying is really you have three different axes, you know. The plane is going side to side, up and down and yawing. You’ve got to coordinate all the elements of that to fly.”

The freedom is the other thing that has hooked Smith on flying. He can land anywhere there’s a strip for ultralight planes, and they’re all over the place — particularly in Idaho.

“Idaho’s Division of Aeronautics probably manages and maintains over 30 backcountry airstrips throughout the state,” Smith said. “One of the biggest joys of my flying has been 12 to 15 of us pilots getting together every fall and flying into the Idaho backcountry for a week camping and exploring the many different airstrips that are supported by the Idaho aviation association.”

Most of those airstrips range from 1,000 to 1,500 feet long. They’re a challenge to the skill and techniques of bush country pilots like Smith.

An Unconventional Approach

At one point, Smith thought he might become a commercial pilot. He was all set to do that, but the pay was disappointing — less even than a starting teacher’s salary at the time.

But he was still able to realize his dream of becoming a pilot by embracing an unconventional approach. He started a health business, One to One Wellness, which in Jackson turned out to be an even bigger hit than he ever thought it could be.

“There’s people who, like me, came to Jackson 30, 40 years ago, and I say they’ve been rode hard and put up wet,” Smith said. “They won’t go to the gym. They ski, they mountain bike and hike and do their sports, but they don’t necessarily take care of themselves.”

Eventually, they come to someone like Smith to help them reclaim the body they didn’t realize they were abusing.

He helps them with exercises to equalize big muscles that have outpaced smaller muscles through overuse, or that help them shore up joints that have been weakened through unintentionally poor techniques or other issues.

“Sometimes you’ve gotta do what you’re really good at in order to do what you really love,” Smith said. “Flying for me is that love, but I’m really good at training, and so I have a whole degree in exercise physiology and a lot of background in that.”

The Big Crash

Smith had one close call when he was a young pilot, and it almost convinced him to give up flying.

It was about 25 years ago. He was caught in a massive downdraft that forced his plane down behind Sleeping Indian, a local Jackson landmark. He and some friends were sightseeing and scouting for bighorn sheep in eventual anticipation of hunting season.

“The plane exploded shortly after we got out of it,” Smith said. “We were rescued by the helicopter I had worked on the previous five years.”

The accident was a wakeup call.

“I learned a lot about forecasts for winds aloft,” he said. “You know really, in the mountains, the winds can be very strong at different times, especially when it is going between the peaks. And then also flying within the performance of your airplane. That’s another big one. Those things are pretty important.”

A year later, Smith was still reluctant to go back up in the air, but he had help from an unexpected friend in Jackson’s bush pilot community.

“I met Harrison Ford while at the airport,” Smith said. “And he had heard about my crash and was very kind to get me back up flying in his De Havilland Beaver. We’ve since continued a great friendship and I have helped him as personal trainer for his work.”

Ford’s not the only mentor Smith credits with helping him become a better pilot over the years.

“Paul Von Gontard at 91 has been a friend and mentor for the past 20 years and is a legend in the flying and ranching world in this part of the state,” he said. “He has used his airplane to assist in all aspects of ranching, including finding cattle, delivering fence posts, etc. He’s a true renaissance man with stories and tales from travels all over the world.”

Gontard has let Smith land his plane at his private airstrip from time to time, which is whimsically named the Melody Ranch International Airport.

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.