SOUTH PASS CITY HISTORIC SITE — Five years ago, researchers at South Pass City State Historic Site had a mystery on their hands.

Ledgers and other records left in South Pass City’s “downtown” and in some of its surviving store buildings suggested that miners had been paid for some sort of a side job, but the records didn’t say exactly what that job was.

Meanwhile, volunteers and workers had found piles of gravel in a strange location, seemingly not directly associated with the mine.

Could there have been an unrecorded vein of gold discovered near South Pass City?

In 2017, volunteers decided to find out. Work had been ongoing at the Carissa Mine, and there was a big trackhoe there with three days rental left on it, Friends of South Pass City member and volunteer Glen Hester recalled.

“We brought it down here, and we started digging back and forth using this dump out here as our gauge,” he said, gesturing to a small drop off that is a hundred or so feet from the opening of what is now known as the English Tunnel.

Finally, after going back and forth, back and forth, and finding nothing at all but more gravel, the trackhoe unexpectedly hit something hard. Further digging revealed a rocky ridge that was different from everything else.

“We were pretty happy,” Hester said. “We didn’t know what was going on, but it was different.”

The driver of the trackhoe took a bucket and stuck it underneath the rocky ridge that he’d just uncovered, to see what might be in there.

But the driver didn’t get just the bucketful of dirt he’d been expecting. Instead, water gushed out, dousing him and everyone nearby.

“It took three days for it to drain out,” Hester said.

It was a century’s worth of water — millions and millions of gallons worth — built up in an old tunnel that had finally been rediscovered.

A Walk Into Darkness

Once drained, Hester and two other men worked on digging out the tunnel entrance, so the men could explore inside.

“We put on rubber irrigation boots and the three of us went in there with no idea what we were getting into,” he said. “No idea. We didn’t know if it was going to be 20 feet or forever.”

What they found inside the tunnel were treasures of a different sort than the gold men had once sought in the hillsides surrounding South Pass City.

“To me, it was like walking into King Tut’s tomb,” Hester said. “It was the experience of a lifetime. We went back in there and we were amazed. We found artifacts everywhere.”

Square nails, half of a shovel and a pie pan, boxes that once contained dynamite, and a pile of chicken bones — the last meal eaten in the tunnel for more than 100 years.

Most of the artifacts they found that day were left in the tunnel, Hester said, so that tourists could come and experience what he and the other two workers had felt when they discovered this tunnel, walking into it for the first time in 112 years.

“Some (artifacts) we picked out that were very delicate,” he said. “They’re downtown in our archives. But most of them we left, so you can experience them like we did.”

Why It’s Now Called The English Tunnel

Since discovering the tunnel, researchers at South Pass have begun to piece together the story of what is now known as the English Tunnel.

Miners following the Carissa lode that had been discovered in South Pass City in the 1860s soon ran into water as they were digging out a mining shaft.

That’s not uncommon when mining substances from deep within the earth. Water is frequently encountered in mines and has to be pumped or hauled out so that the work can continue to drive deeper.

“That (shaft) was dug by hand with a pick and a shovel and a five-gallon bucket , and a ladder coming up out of there,” Hester said. “But they hit water, and they couldn’t mine any deeper. So, they had some mining engineers and they said, ‘Well, back in Europe and over in California, they dig a tunnel underneath the hillside to let the water out. So that’s just what they did. They started this tunnel.”

A group went first to England, however, to find investors for their idea.

“So, you know the name now, why it’s called the English tunnel,” Hester said. “They got all their money from England. Then they came over here and they started digging and they were about 80 feet in when the Gold Rush was basically over.”

The miners who’d once filled up South Pass City, making the population 3,000 to 5,000 strong at peak, took off for the next gold strike in Montana and the Black Hills.

Gravel and dirt slowly but surely covered over the abandoned English tunnel, which filled up with water from the Carissa. The tunnel lay dormant for the next 30 years.

Second Chances Are Short-lived

The tunnel got a second chance after a Chicago lumberman named John C. Spry bought all the mining claims in the South Pass City area. He wanted to be another “Vanderbilt,” and was looking to strike it rich by reviving the Carissa.

When he learned out about the side tunnel, he decided that work should continue anew, and blasted another 240 feet of tunnel, adding to what had been accomplished with English money.

The main idea behind that was still to drain the Carissa of water, but Spry’s section of tunnel does have a couple of intriguing side tunnels. One is in close proximity to a quartz vein. That suggests the side tunnels might have been following a promising new vein of gold, although so far there’s nothing conclusive.

“I can tell you right now, there’s no gold in it because we had it assayed,” Hester told a recent tour group. “But it’s a clue that maybe that quartz vein went back through here, and they mined it out, hoping to find gold in it.”

There’s no evidence of quartz or gold in the rubble dumped from the tunnel, Hester added. It’s believed anything likely to have had any gold in it would have been taken to town, to the creek area for processing.

“We do not know (for sure), and we’re still looking,” Hester said.

In town, there would have been an “arrastre,” which is a device for grinding quartz rock that might have gold in it, was located.

An arrastre is a brick or stone tub with a vertical timber at its center with spokes that would dangle large granite stones inside the tub. The central timber could be turned using either a water wheel or a steam engine. The quartz rock would be added to the tub, and the granite stones would be turned around inside the tub, crushing the rock.

Dyno-mite!

By the time Spry came along, dynamite had been invented, which had superior blasting power when compared to the black powder charges of old.

But the miners continued using the same, old-fashioned hammer-and-drill method that they’d used with the black powder charges to continue lengthening the English tunnel, so they still only managed about 1 foot per day of progress.

With this method, holes were drilled into the rock about 1 foot deep and then charges placed. A miner would then light a short fuse, and book it out of the dark tunnel as fast as possible.

There is a notch in the English Tunnel, near the area where the tunnel branches off on both sides. Mining experts have suggested a canny use for this. Inertia means the force of an explosive blast won’t readily turn a corner. It will instead keep going straight down the tunnel.

That gives the man lighting the fuse an alternate escape route. He could duck into the notch instead — a little insurance, in case of misfire.

But, Hester added, it wasn’t something he himself would want to try, and he’s a certified, licensed blaster in the state of Wyoming.

One Candle A day

The English Tunnel is as cool as an icebox inside, which is refreshing on a hot day. But it is also darker than night itself when flashlights and cell phone lights are completely off.

It is impossible to see anything in the tunnel, even the hand in front of one’s face, or the breath coming out of one’s mouth in the chill air.

“They (miners) were issued one candle per day, and that was their only lighting,” Hester said.

By that light, they would use a hammer and chisel to drill out a foot-long hole in the rock that would then be filled with gunpowder, or later, dynamite.

After the blast, they would work by candle light, shoveling the busted rock into a cart to haul it away.

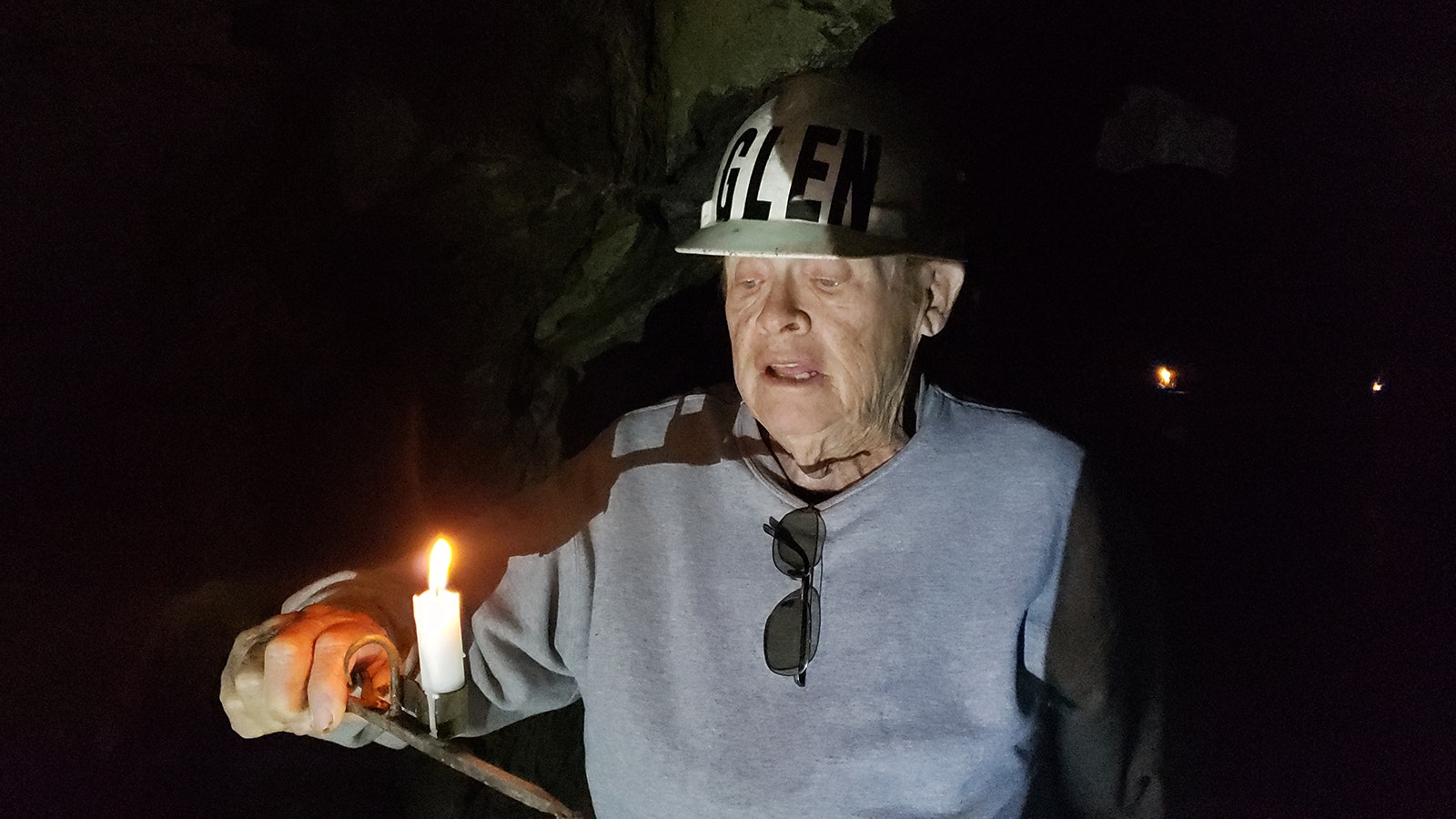

“Something else they had, and we found a lot of pieces of these things, and they’re candleholders,” Hester said. “They’re called Tommy stickers.”

Tommy stickers are found in a lot of the other gold mines dug in South Dakota, Montana, and California.

Replicas of the Tommy Stickers have been obtained to light a dozen or so candles in the tunnel for tours from a perhaps unexpected source.

“It’s called Amazon dot com,” Hester said. “But they are exact replicas of the ones we found in here that were rusted up.”

Locked In Darkness

Spry believes the miners probably didn’t go outside of the tunnel until after sundown, based on what he’s been told touring other old gold mines.

“Their eyes were so dilated it would do permanent damage to their eyes,” Hester said. “So that makes sense to me.”

A Change In The Rock

Spry extended the English tunnel from its original 80 feet out to 320 feet before finally pulling the plug on the operation.

“The rock changed,” Hester said as he pointed to the end of the tunnel. “See where it became real shiny and this out here is kind of dull? They decided there was no chance of them finding any gold any further that way, because there are no quartz veins in it.”

The two aforementioned side channels, meanwhile, each run about 40 to 45 feet before ending.

At the end of the main tunnel, Hester and the men found something very interesting.

“When the three of us got here that first day, at the end of the tunnel, sitting right here were three dynamite boxes,” Hester said. “And we checked them, they were waterlogged. They were just goo.”

Archaeologists later came in and took those boxes away in bubble wrap, Hester said, and they are being kept in town, in South Pass City’s archives for now.

“But the interesting thing about it was, there were three boxes here, and in between two of the boxes was a pile of chicken bones.”

No one knows for certain what the chicken bones were about. Hester’s guess is that the three miners working in the space probably set down a load of dynamite boxes and had fried chicken for their lunch, perhaps not even knowing that would be their last day working on the tunnel.

The tunnel was abandoned in 1905 and soon forgotten. By 1910, it had fallen off the mining records of the state. Dirt and gravel crept over the entrance year after year, and water draining in from the Carissa Mineslowly but surely filled the tunnel with ancient water from deep inside the earth, preserving the artifacts inside like a treasure, until the tunnel’s rediscovery.

If You Go

The English Tunnel is open for tours for ages 7 and up at 11 a.m. on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays June through Labor Day. Reservations are required. For details or to make a reservation, visit online.

The hike to the English Tunnel is a little over a mile. A round trip on the Mohamet and Hermit Creek Trail loop, meanwhile, is 2.7 miles of moderate to strenuous hiking, with a 200-foot elevation change.

Good hiking shoes are recommended, along with water and sunblock. A picnic lunch isn’t a bad idea after the tour, somewhere along the trail home, or make a reservation to eat at the nearby, Atlantic City Mercantile, after panning for gold in South Pass City and exploring the Carissa Mine, which is also open for tours at 2 p.m. Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays June through Labor Day.

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.