Among the many performers who passed through Buffalo Bill Cody’s “Wild West" show there was at least one who sought neither fortune nor fame.

His name was Black Elk, and what the Lakota man wanted was both simple and difficult.

He wanted to understand the white man’s ways, and he wanted to learn how he could help his people.

“Wasichus” — white men — had put the Lakota people onto tiny islands of grass and taken away their teepees that were round like the world. Now they all lived in these ugly, grey boxes made of logs, and there was never enough food.

Their bison relatives were all gone, and the rations promised them did not always arrive.

The hoop of Black Elk’s nation had been broken, and the power of his people was dying.

He could see it all around him.

Worse, the ugly, grey boxes and the pain of his people had all been part of a vision he’d had when he was 9. But he’d also been promised help in the vision and the power to save his people.

Black Elk never stopped searching for that power throughout his life. The time he spent with the “Wild West" show was but one step of many in a lifelong journey.

Fourth Son Of Black Elk

Black Elk was the fourth son to bear this name. All of his forefathers were, like himself, medicine men of no little reputation, though he would one day be considered greatest of them all.

Lakota believed that the Great Spirit would grant their most faithful spiritual gifts to help the people in visions. Such visions were taken quite seriously by the people. There are numerous reports of Black Elk curing people, even one who was very near death.

“I was born in the Moon of the Popping Trees (December) on the Little Powder River in the Winter When the Four Crows were Killed,” Black Elk would tell Nebraska poet and writer John Neihardt through an interpreter. “I was 3 years old when my father’s right leg was broken in the Battle of the Hundred Slain. From that wound, he limped until the day he died, which was about the time when Big Foot’s band was butchered on Wounded Knee. He is buried, here, in these hills.”

Neihardt had come to Black Elk thinking merely to understand the ghost dance for an epic he was writing, “A Cycle of the West.” But Black Elk, who was then in his mid-60s, had more to tell.

He told Neihardt he knew the poet had a desire to know the things of the “other world,” and that he could sense a spirit standing behind him that had encouraged Neihardt to come to him.

And Neihardt, who had also had a vision of his own when he was 11 that had put him on his pathway as a writer, wrote later that he instantly sensed all this to be true.

Black Elk was a man “uncanny” in his intuition, and somehow he seemed to just “know what was inside” a man, he wrote in a letter to a colleague.

Telling the story of Black Elk became Neihardt’s calling. But it was also going to take special preparation.

Black Elk told Neihardt to come back in nine months. He would have everything ready then.

A New Son

When Neihardt returned, a teepee of white duck had been erected and the flaming rainbow, which came from Black Elk’s vision, had been painted above its doorway.

Vision power symbols from Black Elk’s dream, when he had lain for 12 days in a vision state, had been carefully painted on the sides of the teepee as well. A finishing circle of fresh-cut pine trees had been thrust into the ground around the whole area, and it smelled fresh and green.

In front of the teepee there was also a small, circular dance bower constructed of fresh pine boughs.

The teepee was lodging for Neihardt and his daughters, who had come as stenographers and observers. But it would also set the scene for Black Elk’s visions, which in Lakota traditions are shared by re-enacting them. These included live horses and people dressed as they had appeared in the vision, saying — or sometimes singing — what had been heard.

But before Black Elk could share this sacred vision, there must be a feast and games of old. The history of Black Elk and the Lakota people would be told as well, in preparation for a particularly special ceremony.

Black Elk would first take Neihardt as his son, so that he could share all that he knew.

Wounded Knee

Included in the history that Black Elk told Neihardt is a firsthand account of the massacre at Wounded Knee which, like Black Elk’s birth, also happened in the Month of Popping Trees.

The Wasichu had become concerned about the Ghost Dance religion that was sweeping the reservation. The people were dancing and receiving visions, but officials believed this was stirring up the tribe and that it would cause trouble. Orders came down that the dancing was to stop, and soldiers were sent to enforce that.

Black Elk was among men on their list for arrest.

As one soldier struggled with an Indian named Yellowbird, who did not want to give up his weapon, the gun went off.

According to some accounts, the soldier was killed and in others he was wounded. But in either case, with tensions running so high between Indians and white men, the shot itself was a spark, and it landed in a powder keg.

Black Elk, in his account to Neihardt, tells of riding to the scene to try and rescue as many as he could.

“I had no gun,” he told Neihardt. “I carried only the sacred bow of the West that I had seen in my great vision.”

At a spot Black Elk said is sometimes now referred to as Battle Creek, he could hear shooting and many cries.

“We could see Cavalrymen scattered over the hills ahead of us,” he told Neihardt. “Cavalrymen were riding along the gulch and shooting into it, where the women and children were running away and trying to hide in the gullies and the stunted pines.”

Charging In

Black Elk had about 20 riders with him.

“Take courage,” he told them. “These are our relatives, and we will try to get them back.”

After that, he sang a sacred song to strengthen and protect them all.

“A thunder being nation I am, I have said,” he repeated twice. “And then, ‘You shall live,’ he repeated a sacred four times.

After that, they charged into the soldiers, who shot their weapons at them as they came.

“When we were charging, I just held the sacred bow out in front of me with my right hand,” Black Elk told Neihardt. “The bullets did not hit us at all.”

They ushered some of their relatives to a bridge to the northwest where they would be safe, and pushed forward to where the soldiers were.

“By now, many other Lakotas, who had heard the shooting, were coming up from Pine Ridge, and we all charged on the soldiers,” Black Elk said. “They ran eastward toward where the trouble began.”

Black Elk and the other Indians followed to drive the soldiers away. Throughout this time, bullets flew at them and Black Elk could feel them whizzing past. But he kept his sacred bow raised, and none hit them that day.

“What we saw was terrible,” Black Elk said. “Dead and wounded women and children and little babies were scattered all along there where they’d been trying to run away.”

Death Of A Dream

When Black Elk finally returned to where he and his people had been camping, everyone had fled. He finally found them and heard his mother singing his death song.

She had thought he must have been killed in the fighting.

The next day, the people were gathering, and everyone was talking about a much bigger war party to go and meet the soldiers to take revenge.

“But this was hard, because the people were not all of the same mind, and they were hungry and cold,” Black Elk recalled.

Meanwhile, Chief Red Cloud came to talk his people down.

“(He) made a speech to us, something like this: ‘Brothers, this is a very hard winter,’” he said. “‘The women and children are starving and freezing. If this were summer, I would say to keep on fighting to the end. But we cannot do this. We must think of the women and children, and that it is very bad for them. So, we must make peace, and I will see that nobody is hurt by the soldiers.’”

Everything Red Cloud said was true, and so the people agreed to lay down their weapons.

“And so it was all over,” Neihardt wrote in his book, “Black Elk Speaks.” “And … something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream.”

Fulfilling A Destiny

The day Neihardt arrived, Black Elk had just turned away another writer seeking to know his story.

But bringing all people together was central to Black Elk’s vision, and he felt that Neihardt, who was seeking to know so much more than just history, was a sign — one that he’d been waiting for for almost all of his life.

He wanted to share the vision he’d seen in which the hoops of all nation became one, and the one tree at the center of it all would bloom anew. Neihardt could help him tell the world of this, so that this dream for all of humanity could come true.

That, too, may not have been as clear in Black Elk’s lifetime as the Lakota spiritual leader could have wished.

While Neihardt’s 1931 book drew critical acclaim during Black Elk’s lifetime, it would not strike a nerve until the 1960s, almost a decade after Black Elk’s death.

Since then, the book has only increased in popularity by those who believe in his vision, and notoriety from those who don’t.

Black Elk Debates Continue

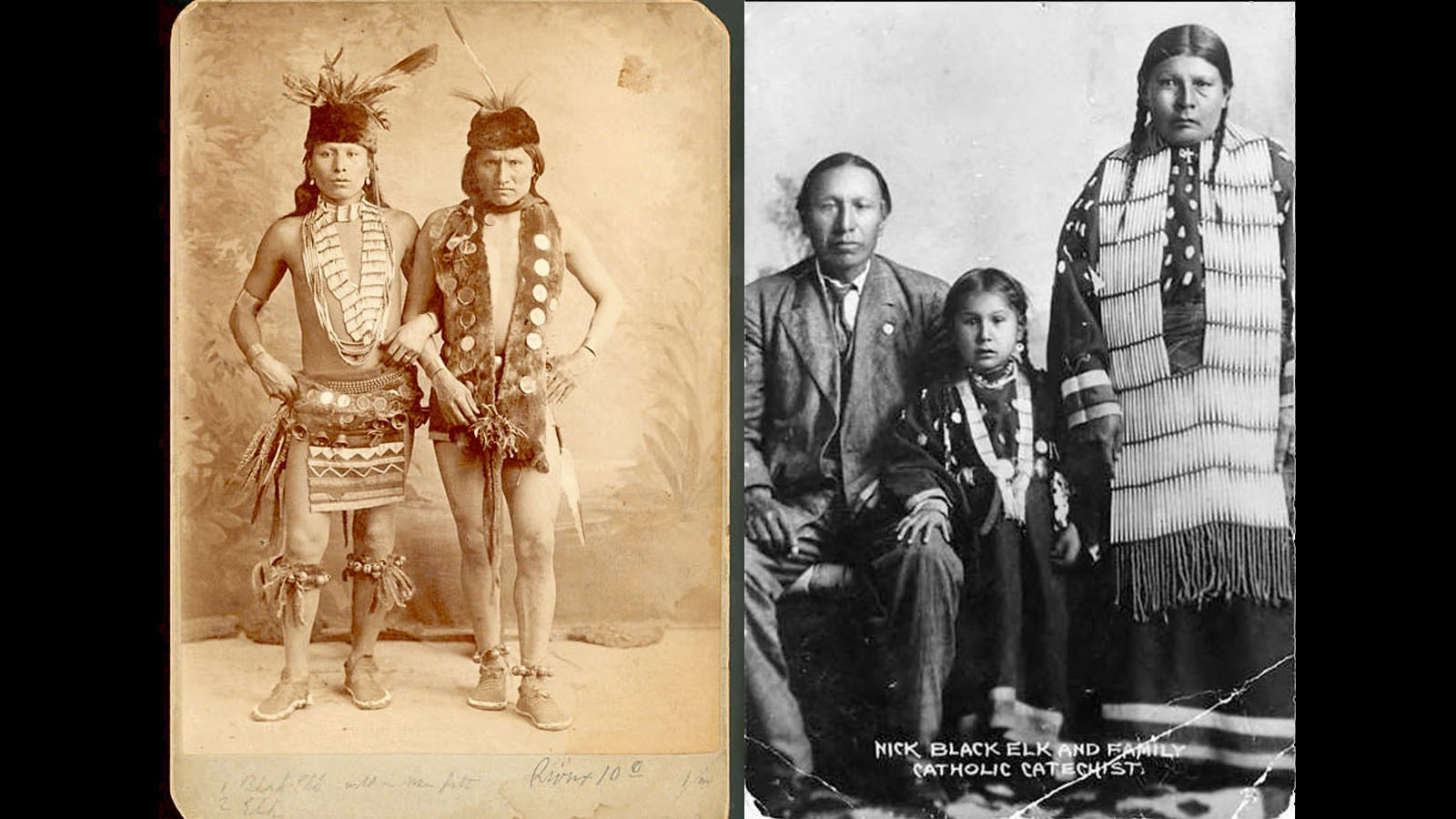

Black Elk, by the time Neihardt had found him, was no longer living as a traditional medicine man. He had converted to Catholicism not long after the Wounded Knee massacre and the death of his first wife, when he was in his 40s.

He served as a catechist for the church. He was a visible leader of the Catholic Church on the reservation in South Dakota where he and his people now lived, leading thousands to Christ.

The conversion to Christianity and the vision that Black Elk related to Neihardt has had scholars arguing for decades about whether Black Elk did or did not mean to convert to Catholicism, and whether he did or did not believe the visions of his youth.

The Catholic Church, meanwhile, opened a canonization cause for Black Elk in 2016, while the U.S. Board on Geographic Names renamed South Dakota’s highest peak, Harney Peak — where Black Elk says he was taken during his vision — to Black Elk Peak.

While scholars will probably continue debating what Black Elk did or didn’t believe, relatives say he believed both things and saw nothing incompatible in them.

“He had decided that the Sioux religious way of life was pretty much the same as that of the Christian churches, and there was no reason to change what the Sioux were doing,” Frank Fools Crow told writer Thomas Malis.

Scholars will continue to disagree on the finer points of Black Elk’s story. But the fact the world has continued talking of his vision, in which all humanity became one, was exactly what the Lakota spiritual leader wanted when he told Neihardt his vision of the sacred hoop of all nations, and a tree at the center of it all, which he hoped would one day bloom anew.

Contact Renée Jean at Renee@CowboyStateDaily.com