Drea Hineman, a senior at the University of Wyoming, grew up gardening with her grandfather in Gillette. Now, her novel agricultural research could help revolutionize gardening in space.

Hineman is a research fellow with the Wyoming NASA Space Grant Consortium, which sponsors education and research that can support long-term space missions. Her research is solving one of the most critical problems with "space farming."

"Space farming sounds crazy, but it's really important to understand plant behavior in reduced gravity," Hineman told Cowboy State Daily. "NASA is focused on staying in space for an extended period of time, and they want astronauts to have fresh food."

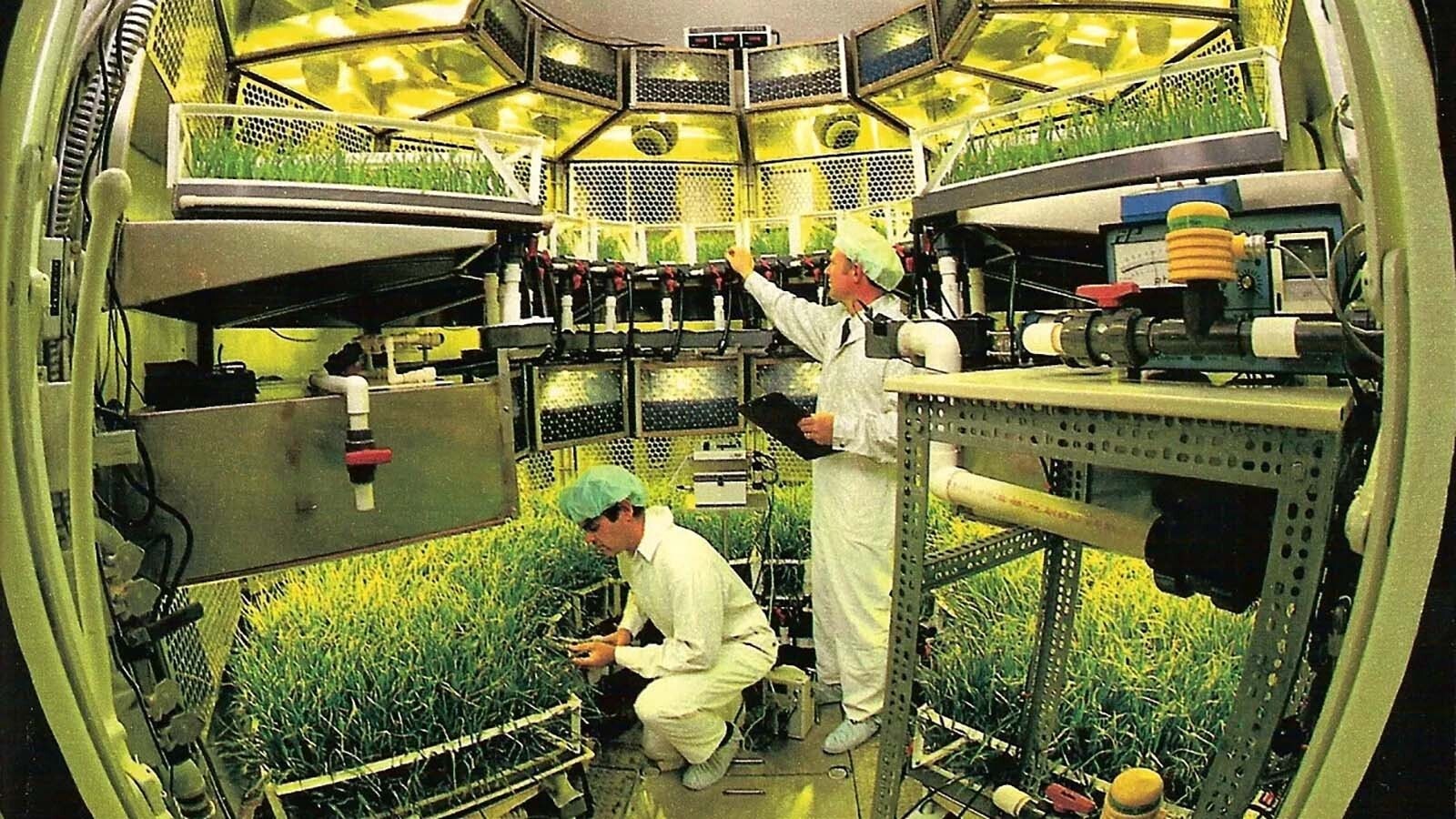

Using special systems that mimic water movement in reduced or zero gravity, Hineman has developed a system that will allow fresh lettuce to be grown and harvested in space, and potentially on the Moon and Mars. And she did it all in a greenhouse in Laramie.

"It is quite cool living in a town where I can talk to people about what their agricultural past looks like and share my perception of agriculture that's a lot different," she said.

Salt In Space

For as long as there have been astronauts, there's been an urgent need to keep them healthy and alive. A staple of space travel is dehydrated meals, which have sustained astronauts for decades but leave much to be desired.

"Astronauts really do not like them," Hineman said. "They're not fun to eat. Sometimes they'll try rehydrating it, adding the air and water, and it'll still be hard and crunchy. Now they want to be able to take food to space that is actually fresh, so that means something they can eat and cultivate up there."

Space farming has been done before. The techniques Hineman mastered in the UW greenhouses were pioneered by NASA astronauts on the International Space Station.

There's one big issue with farming in space: the lack of gravity.

"When plants go to space, they have all of their water just inside of a plant pillow," Hineman said. "It holds all the plants, and no water can exit, because gravity is holding it within the plant pillow."

Since the plant pillow is impermeable, none of the water, substrates, or slow-release fertilizer inside can drain out of it. That leads to salt accumulation, a serious problem when farming a crop on Earth, let alone in a plant pillow in space.

"Salt is accumulating because water is not exiting any of the plants, because gravity is holding it with them," Hineman said. "That makes for un-tasty plants that aren't growing as well as they should."

Previous NASA research showed that salt accumulation was a serious problem hindering space farming. That was the problem Hineman decided to address.

"For my space farming research, I focused on how to get the salt outside of this plant pillow or mitigate the salt stress in the soil so that plants can grow in space," Hineman said. "That was my drive."

The Right Student

Hineman is majoring in plant production and protection in the UW Department of Plant Sciences. Her project to study sustainable food production in reduced-gravity environments was the top choice for a 2025 NASA undergraduate fellowship grant.

"This is her own idea, her own research," said JJ Chen, an assistant professor in the Department of Plant Sciences and Hineman's mentor.

UW has an automatic sensor-based irrigation system, provided by NASA, that mimics the movement of water in reduced and zero gravity. Chen incorporated Hineman's salinity project into ongoing research on plant behavior in reduced-gravity environments, with the eventual goal of developing strategies for farming on the moon.

"I like to joke that UW is the only university that can do this research, because our elevation makes us closest to the moon," Chen said. "Having this technology allows us to continue and expand our research and improve these space irrigation systems."

Hineman acknowledged she knew nothing about space farming when she came to UW. Chen recognized her interests and aptitude and selected her for the project.

"I knew I wanted to do a job in greenhouses or controlled environments," she said. "JJ was the person offering all the greenhouse and environmental instrumentation classes at UW. It was mainly showing my interest, JJ noticing it, and assuming I'd probably like to do this as well."

Cut And Come Again

Using lettuce as the crop of choice, Hineman designed and conducted a series of experiments to examine salt tolerance in lettuce under environmental stressors in reduced-gravity environments.

"We've learned that they have grown lettuce already in 'Veggie,' one of the space pillows that have been taken to space," she said. "They also learned how they can harvest it correctly, so I did a 30-day, 48-day, and 56-day harvest."

Through these experiments, Hineman can determine that salinity tolerance differs across different growth stages. She called it the "cut-and-come-again" harvesting method.

Her research also examines the interactions among lettuce, fertilizer rates, and bio stimulants. The goal is to produce the best produce possible, grown in space using the already-established irrigation system to reduce salinity stress and enhance the productivity of space farming.

"NASA wants to figure out how we can survive in space long-term," Chen said. "Having a sustainable food supply is really important, because we cannot keep supplying missions as we have with the International Space Station. Drea's focused on sustainable space farming for one to three months in space, in preparation for an eventual human habitat on the moon and beyond."

Sticking Out Like A Green Thumb

In October, Hineman presented her ongoing research at Interplanetary Life, a conference on space-related science. It was hosted by Spacepoint, an educational nonprofit that raises awareness of advances in the space industry, in Boise, Idaho.

A variety of scientists, engineers, and astronauts presented on topics ranging from spacecraft propulsion to biomedicine. Even in this excitingly niche field, Hineman stood out like a green thumb.

"Not only was that my first conference, but we were the only plant people there," she said. "I got to learn about a lot of new things, but people also got to see that space farming was something to be excited about."

The next step in Hineman's research is attempting to mitigate the impacts of salinity stress on space-farmed produce. She plans to inoculate the lettuce plants with fungi to see if that will help them grow healthier and more sustainably.

Chen is thrilled with Hineman's success, as are his NASA contacts at the Kennedy Space Center.

"Since we're still testing, we regularly report Drea's findings and results," he said. "I was just talking with them, and they are very excited and happy about the current progress and, what I would call, this investment in UW. They're using the results of this research for the future of space agriculture and exploration."

Solving the problem of salinity stress would be a tremendous advancement in space farming, broadening humanity's possibilities within the final frontier. Hineman never expected to make such a meaningful contribution to our future in the cosmos.

"I didn't think that I'd get this far," she said. "I never thought that I'd be capable of this. I've had a lot of guidance from JJ, but it all started with showing my interest."

And will NASA decide to let Hineman demonstrate her technique by taking her into space?

"I really want them to, but we will have to see how it goes when I graduate," she said.

Andrew Rossi can be reached at arossi@cowboystatedaily.com.