Retired Wyoming Chief Game Warden Rick King has gotten used to hearing one particular phrase everywhere he goes.

“When I tell people what I did for a career, their first response is, ‘Oh, you’re Joe Pickett,’” King told Cowboy State Daily. “That’s fun. That’s a great way to connect with people, and I appreciate what it’s done for the profession.”

King was a new game warden when New York Times best-selling author C.J. Box’s first Joe Pickett book, “Open Season,” came out in 2001.

King said he bought it out of curiosity, then couldn’t stop reading it.

“I really enjoyed the description of what the life of a game warden is really like,” he said. “And I think the Joe Pickett character mentioned something like he had moved nine times and lived in five different houses.

"That’s not an exact quote, but that was similar to the experience that my wife and I had. We moved eight times, and so I could just relate to that.”

King finally got to have his copy of the book signed by Box recently during a University of Wyoming law symposium.

Designed for up-and-coming legal eagles, the symposium was a deep dive into all the legal issues Box has explored in his creative books, like the “Zone of Death” in Yellowstone National Park, where technically no one has legal jurisdiction to prosecute a crime.

King came to the symposium with colleagues Dan Smith, the state’s chief game warden, and Martin Hicks, who is deputy chief of the Wildlife Division of Wyoming Game and Fish.

Getting his first-edition “Open Season” book signed by Box was a full circle moment for King, a loop that’s taken him nearly 25 years to close.

The novel, King said, is special to him. It was such a difference maker in his life and in his career.

Because people would instantly identify him as the real-life “Joe Pickett,” it helped smooth many interactions over the years, King said. It also helps build an instant connection with people.

But it was also helpful with people he knew well, too.

“I don’t think a lot of my family members understood what I was doing, what the profession was,” he said. “But through these books, I think they’ve been able to get a deeper sense of what the career and life of a game warden is. So that’s been pretty special.”

World Not Waiting For Game Warden Series

Box never intended to create a series about game wardens at all.

“I didn’t think the world is just waiting for a Wyoming game warden book,” Box said of his popular series. “When I first started out to write fiction 20, 30 years ago, I wanted to write a book that was true to what my version of Wyoming was.

"And that is not people who kind of speak with southern accents … (where) everyone’s a caricature from a Western movie.”

Box said he also wanted to include “tip-of-the-spear” issues that are highly relevant to the modern-day West, “issues that we all know about in Wyoming, like energy, development, wilderness, individualism, environmentalism, outfits and guides, hunting and fishing culture, federal versus state versus local control, outdoor and Western culture.”

Box spent 20 years thinking about his first book, what issue it should be about and who the star should be.

Ultimately, he chose the Endangered Species Act for his issue, with a theme centered on what it looks like when well-meaning legislation goes awry on the ground.

“I based it on discovery of black-footed ferrets around Meeteetse so many years ago, and what really happened as a result of that fascinating kind of new West issue,” Box said.

His first thought for the hero was a sheriff, but as he thought more about it, that didn’t seem quite right. He shifted to thinking of the hero as a journalist, which was what he himself was doing at the time.

That wasn’t right either.

Eventually, he realized that the very best eyes to tell the story would be a Wyoming game warden. They were the guys on the front lines of that change.

Game wardens would be an unusual choice, Box realized. But he didn’t figure it mattered that much. This wasn’t some sort of series, he told himself then. It was a one-off.

“I never thought there would be a second book,” Box said.

Dead Agents Don’t Sell Many Books

In fact, the game warden hero was so different, it made Box’s first book very difficult to publish.

“I got an agent in New York, and this is pre-Internet, so I had to send the manuscript through the mail to a guy who had expressed interest,” Box said. “And then I waited two years, three years and nothing was happening.”

One time when Box called the agent told him, “I can’t place this novel, it’s too different. It doesn’t really fit a genre. It’s set in a place nobody knows anything about. And it’s a game warden.”

Box waited another two years, and still nothing was happening, so he decided it was time to take matters into his own hands. He went to a writer’s conference in Colorado that included some pitching.

“So I pitched this to a different agent, and he was interested,” Box said. “And he said, ‘Do you have an agent?’ And I said, ‘Yes, but nothing is happening.’ And he said, ‘What’s his name?’ And I told him his name and he said, ‘You don’t know he’s dead, do you?’”

Box got a new agent right then, but he also found a publisher as a result of the conference.

“This 24-year-old editor from Putnam heard the story and was kind of intrigued by the book, so she contacted me,” Box said. “And then they offered the contract for two more Joe Pickett books. So, the series was born at that point.”

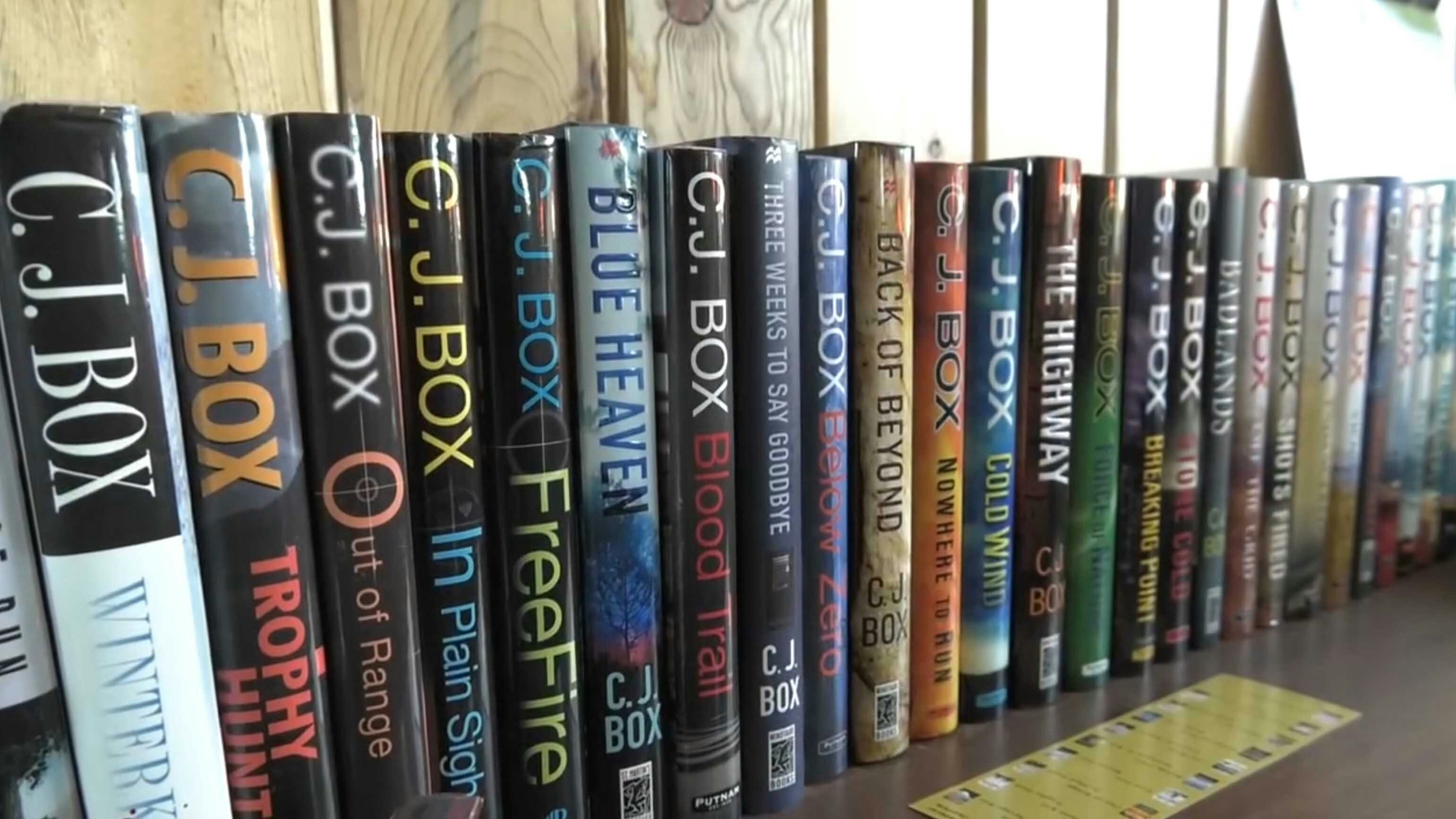

Twenty-six books later — some of them New York Times bestsellers — with copies that have been translated to countless languages around the world, Box can say he’s successfully made the case that the world was indeed waiting for a series about game wardens after all.

They just hadn’t known it.

What Being A Game Warden Is Really Like

What’s striking to the game wardens themselves is how Box has elevated their profession across America, while also educating people on all the real-world issues they face with his ripped-from-the-headlines stories.

Box said he interviews people on both sides of every issue he’s interested in exploring, and then lets different characters in the story reflect each viewpoint to readers, trusting them to make their own conclusions about who is right and who is wrong.

That’s led to praise from opposite sides of many issues telling him he got it exactly right.

Box has also been known to do his own deep, real-world dives into experiences that help him write his books, like two-week Yellowstone pack trips or climbing an actual wind tower.

By doing that, Box learns things like the fact that wind turbines don’t have elevators like he was thinking at all. They have tiny ladders to climb all the way to the top.

But maybe there’s just a bit more excitement in one C.J. Box book than there is in a whole Game and Fish career, Smith said, chuckling a little bit. His day-to-day life as a game warden has been significantly duller than a Joe Pickett adventure would suggest.

“A lot of our job is public relations with hunters and anglers,” he said. “We are working with landowners, educating people, as well as enforcing the law.”

But he wouldn’t trade the job, either. It may not be full of excitement, but every day is a bit different. He likes the variety.

”Some days, you get woken up in the middle of the night to go take care of an injured animal,” he said. “Some days you sleep a little later in order to work later. An average day for a game warden is, I call it the greatest job ever, because there is no average day. Every day is different.”

King, meanwhile, believes a game warden’s whole job is a lifestyle in and of itself.

“If you work for the fire department, we work these 48- or 72-hour shifts, where you live in the fire hall for that amount of time and then you go home,” he said. “But being a district game warden in Wyoming is like being in a fire station 24/7 or 365.”

Box’s novels capture the “essence” of that really well, King said.

“I appreciate that, because it helps provide a lot of points you might otherwise have no clue what a game warden does,” he said. “It’s really helped shape people’s opinions and gets an accurate portrayal of the life of a game warden.”

Ethical Dilemmas Are Real

Smith loves the way Box captures the dilemmas that game wardens face as they do their jobs.

Those range from ethical issues to family and other pressures.

“We have this obligation to enforce the law, but there’s times that people make a mistake, and there’s other ways to enforce the law that doesn’t involve writing a ticket,” Smith said. “You can write a warning, to try to educate and teach them a different way to do it.”

Particularly with youths, who might have done something acting under parental influence, Smith leans more toward education than punishment.

“These kids aren’t always making these decisions on their own,” he said. “So if I can point them in the right direction, give them a break and say, ‘Here’s how we need to do it in the future. Here’s how we need to move forward.’”

King, meanwhile, appreciated how Box captures so well the tension between duty to the job and duty to self and family.

“Joe Picket struggles with that a lot, and I can tell you from experience, and watching game wardens, that’s a very real dilemma and struggle,” he said. “It’s tough to feel like you are doing your duty and doing your job and meeting the needs of the public, but it’s also tough to do that and take care of a family and meet those obligations and duties and responsibilities.”

Hicks, meanwhile, said he thinks he’d make a terrible game warden because he would just let everyone off.

Game wardens "are wired differently,” he said.” And it’s because they have to make some really hard decisions.”

Yes, Game Wardens Really Are Hard On Vehicles

As for whether game wardens are as hard on vehicles as Joe Pickett, Smith said at least some of that reputation is justified.

“We expect our game wardens to go to all kinds of places, and all kinds of weather,” he said. “And so equipment is damaged, and we try to do our best.”

Smith can tell some pretty funny stories about things that happened to vehicles over the years. Like the time one of his technicians got a new truck and managed to seriously damage it in less than a month.

Smith had told the technician as he was handing over the keys to the new truck, “This is a brand-new truck. Now I know some of those dents (in the old truck) were from you, from the last truck. And you kept saying these aren’t mine.

"But this is a brand-new truck, so any dent moving forward is yours. It’s your responsibility.”

Two weeks later, Smith got a call from the technician.

“He says, ‘Hey, I got this little bitty, little bitty scratch,’” Smith recalled. “'I just want to make you aware of it. It’s not a big deal. You probably don’t even want to fix it. It’s not really a problem.'”

Smith decided if the employee was working this hard to downplay a “little bitty” scratch, he’d better take a look for himself.

On his way to see the truck, he got a call from someone at the check station asking him what had happened to the technician’s truck.

“Sounds like it’s not a little scratch,” Smith told the caller, who laughed a little bit and then said it was actually a great big hole in the side.

“So he had turned a corner on an icy alley in town, trying to avoid hitting a deer,” Smith said. “And he hooked the hook on the dumpster there, and didn’t stop, so it created a nice, big hole.”

When Mountain Lions Fly

Game wardens take some crazy calls, Hicks said.

He recalled the time he was working near Springer, a wildlife habitat management 15 miles south of Torrington, and got a call from a gentleman about a mountain lion on a cliff that “wouldn’t leave.”

Hicks was a little puzzled by the caller and suggested that if the man left, the mountain lion would probably also leave.

“So, he’s like, ‘No, no, no, you don’t understand,’” Hicks said. “'We saw it this morning, and it’s still there. It will not leave.'”

Hicks wasn’t thrilled about driving all the way over to Grey Rocks Reservoir where this mysteriously stubborn mountain lion was, but he felt it was important to maintain a good relationship with the locals. Part of that was answering their calls, even if they seemed on the surface a bit wonky.

When he arrived, the man had been fishing in a boat with his adult daughter and granddaughter at Gray Rocks Reservoir. Hicks got into his boat to head to where the mountain lion was with the man as there was no other way to get there.

It was a sheer cliff, Hicks saw when he got there, with no real way for wildlife to climb up or get back down. The mountain lion, meanwhile, was sitting in a small cut-out space.

“I had no idea how that mountain lion got into that,” Hicks told Cowboy State Daily after the law symposium. “She got scared somehow, got down in the water. And there was really no way for her to get out. It was a sheer cliff. And it was right where people could see her, so I knew we were going to continuously get calls.”

Hicks decided to put the lion to sleep, intending to climb up the rocks to get it.

“I didn’t realize I’m not a very good rock climber,” he said.

He considered rappelling down the cliff wall, but the rope seemed thin and sketchy, and he knew his experience at rappelling was even sketchier.

So he called a different game warden named David to come bring him a ladder and come help get this young mountain lion down from the cliff.

“So we dart the lion again, and it falls asleep,” Hicks said. “And we go back up there to get it.”

They tied a rope around the mountain lion so they could lower it from the cliff. Unfortunately, they hadn’t used enough drug and, when the cat fell into the water on the way down, it started to wake up.

It wasn’t really a fan of its rescuers, so it swatted a drowsy claw at a button on David’s pants.

“And he’s such a calm gentleman,” Hicks said. “So he just looked at that and said, ‘Hey, she’s got my pants.’”

They brought the mountain lion to shore, placed an ear tag on her and let her walk stealthily away into the Wyoming wilderness.

“We know no one harvested her, because if you harvest a lion, you have to check it in,” Hicks said. “And so this was years and yeas ago, and we never checked her through a harvest. So I’m assuming she’s out there living her life somewhere along the Goshen Rim.”

That story always makes Hicks feel good.

“As biologists and game wardens, we deal with a lot of death,” he said. “To put it bluntly, we have to put down a lot of animals and it’s not very fun. This is one day where I felt like I won.”

Maybe that encounter with a stranded mountain lion will find its way into a future Joe Pickett novel.

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.