Emmer wheat is one of the oldest grains known to man, cultivated at least as far back as 12,000 years ago in Turkey and Greece. It is the precursor to bread and pasta wheats, which the world consumes voraciously.

But it’s little grown anymore save in Italy, where it’s more commonly known as farro.

Now comes a new Wyoming product that looks to resurrect this obscure grain and make it popular again, with the hope it can help family farmers in Wyoming and the Rocky Mountain West with a new, higher-value premium crop.

The University of Wyoming’s Neolithic brand has teamed up with a Longmont, Colorado, company called Dry Land Distillers to create whiskey made entirely from emmer wheat grown in Wyoming.

Whiskey has long been a popular product in the American West. But emmer is a very unusual ingredient for it. There’s only one other product that uses emmer; a bourbon from Weller, which now goes for $3,000 a bottle. Dry Land’s 100% emmer wheat whiskey is $129 a bottle.

Being a bourbon, emmer can’t be a majority of Weller’s mash, said Nels Wroe, owner of Dry Land Distillers.

“Bourbon by law has to be 51% or more corn,” he told Cowboy State Daily. “So, we’re the only ones making a true 100% emmer whiskey, where you can actually get the flavor of this ancient grain. And we’re proud of it.

"I mean, this is a very true, very rare Wyoming whiskey, and it’s the only one like it in the world.”

Where’s The Authenticity?

Wroe has deep Wyoming roots, himself, growing up in Douglas and Jackson Hole. The grains he’s using, meanwhile, come from the Powell area. That makes this Wyoming born and raised whiskey personally meaningful to him.

“My mom lives in Powell where this grain is grown,” he said. “So, there’s a really strong connection to place for me. My in-laws are up in Sheridan, and I’m a graduate of University of Wyoming, so this has been a very much going-home project for me, which is really, really important.”

Wroe became interested in ancient grains like emmer when he first began exploring craft distilling. He interviewed several start-up craft distilleries, including Wyoming Whiskey.

But Wyoming Whiskey, he learned, was a very different model from most other craft distilleries in the West. Where Wyoming Whiskey uses Wyoming grains and Wyoming water and ages its whiskey in place in Kirby, Wyoming, Wroe learned that was actually pretty unusual.

“I was doing all this research around startup distillers in the American West at the time, particularly in Colorado,” he said. “And I was disappointed that most of them were buying alcohol produced from Kentucky or Indiana.

"They were buying bulk bourbon, bringing it into Colorado, blending it with water, and then, in the case of Colorado, putting a label on it with mountains and saying it was Colorado.”

That didn’t sit well with Wroe’s Wyoming sensibilities. Where was the authenticity?

“I just had a problem with that,” he said. “The West is where I’m from. At some point you are a creature of where you’re from, so I felt like let’s honor Colorado and the American West. Let’s find grains, let’s find ingredients that are appropriate in place.

"Let’s see if we can do some good while we’re making great products and really explore and celebrate the flavors of the American West.”

That’s become the motto of his company, Dry Land Distilling, which channels ingredients that are either native to the West, or that fit the West and its climate. Prickly pear cactus, spruce, and drought-tolerant, ancient wheat, like emmer.

Emmer whiskey’s flavors, Wroe added, are “gorgeous” with hints of cocoa and coffee, grass and leather, and apricot at the start, with a finish that brings in notes of caramel and earth. All good cowboy things.

“I love it neat, on its own,” he said. “it’s a rich, silky, and complex, single-grain whiskey.”

More Than Whiskey

But it’s not just about unlocking the flavors of the West and showing them off for Wroe.

He is also conscious that farmers and ranchers in the West have long been caught in an economic vise, one where operations have to get bigger just to stay alive and survive, much less thrive.

So, when he heard about University of Wyoming’s First Grains project, which seeks to develop higher value specialty crops that Wyoming growers can produce to improve their farm’s economics, he was all about it.

“I’m looking at the sense of community and building and supporting our growers throughout the Mountain West,” he said. “Moving small growers away from this commoditized model that has been a bit of a burden for them for a long time.”

Farmers and ranchers have long been price takers, rather than price makers, he added.

“It’s tough when you’re a smaller or midsize grower, because you’re kind of forced to grow what the commodity markets need,” Wroe said. “And price points make it very difficult to survive, so this (ancient grains) economic model is really interesting to us.”

An Aha Moment In A French Castle

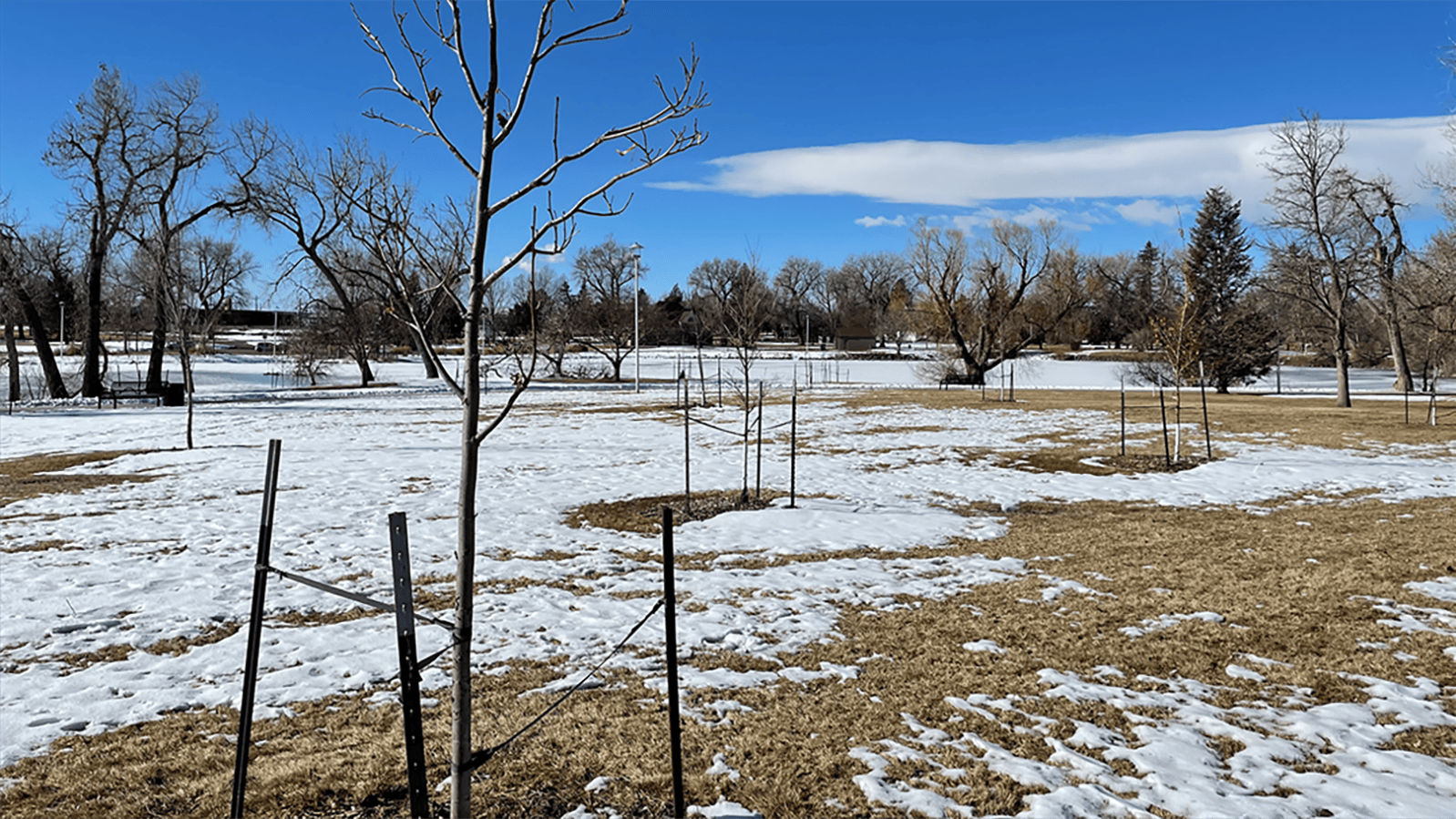

First Grains Program Director Thomas Foulke, who is an agriculture economist for the University of Wyoming, told Cowboy State Daily that the Bighorn Basin’s microclimate is particularly suited to growing many ancient grains, particularly emmer and spelt, which he first learned about during a trip to Europe one summer.

“I was in France, and I was in a castle where I bought this cookbook,” he said. “It had different words for emmer wheat and spelt in there, and I didn’t know what they were. So, I had to dig around and find the translation.”

Once he figured out that these were ancient wheat grains and started learning more about their growing habits, he started wondering why these grains weren’t grown in Wyoming.

They seemed like a natural fit to him. Not only should they be well-suited to the climate, but they offered higher nutrition profiles, and interesting flavor as well.

“So I’ve been working on this for about eight years now,” Foulke said. “And the original idea was and still is rural economic development to create jobs and enhance income in rural Wyoming’s economy. So basically, give farmers an alternative crop, a premium crop, that would allow them to enhance their incomes.”

Foulke thought bread flour and malt for beer sounded like reasonable first products for emmer, which has a complex nutty, but pleasant, flavor.

“I had initially discounted whiskey because it’s such a specialized production,” he said. “You really need to know what you’re doing. I’m an economist, so I don’t know, I didn’t know, anything about whiskey. But I had sold some grain to a mill in Colorado, and they knew Nels, and they had been talking about it.”

That’s what finally brought Wroe and Foulke together for their one-of-a-kind emmer wheat whiskey.

Whiskey is a much better first product for emmer than either bread flour or beer, Wroe said. That’s because it takes 25 pounds of emmer wheat to make just one bottle of whiskey. That kind of concentration means growers can be paid much more handsomely for their efforts.

Powell-area grower Corey Forman told Cowboy State Daily the crop is so far “cash-flowing” quite well, in spite of its lower yield.

How To Malt Organic Glue

Harvesting emmer is a little more difficult than wheat, but not too difficult, Forman said.

Making whiskey out of emmer, though, was another matter. There was a lot of trial and error, particularly at the beginning.

“These grains behave differently in the malting process from regular wheat or barley,” Foulke said. “If you get them too wet, they just turn into like organic glue.”

Wroe teamed up with a couple of different malting companies to finally find a malting process that would work.

“They were brave and through a number of really substantive failures in the malting process — even to the point of requiring air chisels to chisel out the grain that was a failed malting project from their kilns,” Wroe said. “I mean, it was a mess. But we got there, and that’s something we are known to do, is work with these ancient grains that don’t react the way you would expect them to in the process.”

Proving out the grain, however, has been worth it, Wroe believes. The whiskey tastes fantastic, and it’s a product that can offer growers a new alternative as markets get built around this specialty crop grain.

“As we look at choosing these grains that are appropriate for growing in regions like the Bighorn Basin of Wyoming, we can kind of start to change the lens and change the model of our small and medium-sized growers,” he said. “And I think that’s a really, really important thing as we look at how we sustain the American West, not only environmentally, but also from an economic and cultural perspective.”

What Gets Lost To Convenience

One of the other areas where emmer could thrive, Foulke believes, is the health food arena, which has an increasing number of people interested in the nutrition profile of their food.

Modern wheat varieties were bred for certain conveniences, Foulke pointed out. They had better yields, made for easier harvests, and were more compatible with the automated machinery that large-scale bakeries use to produce baked goods. That’s led to a starchy wheat with fewer nutrients than the grain once had.

“We know there’s higher iron, manganese and zinc in these older varieties,” Foulke said. “And so that’s one of the things we’re doing is trying to recapture that.”

Ancient grains also have better flavor profiles, Wroe added, and that’s why he believes it’s ultimately made such a great-tasting, interesting whiskey.

“Emmer is part of human history, being one of the first cultivated grains,” Wroe said. “I mean this is going back about as far as we can go, looking at, can we create something that is culturally and historically significant that hasn’t really been done before.”

It’s also a product that both Wroe and Foulke hope can be part of writing a brand-new chapter in humanity’s wheat history, helping to revitalize the Rocky Mountain West’s struggling agriculture sector along the way.

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.