HUDSON — Alan Simpson grabbed Mike Dabich by the arm at halftime during a high school basketball game in Cody. It was around 1961. Dabich had just torched the home team for 28 points and 14 rebounds in the first half, and Simpson — who would go on to represent Wyoming in the U.S. Senate for 18 years — pulled the young giant close as he came around the corner near the bench.

"You better knock it off, Dabich," Simpson said, "or I'm going to slap the shit out of you."

Every time Dabich saw Simpson after that, Simpson would grin and say he was lucky Dabich didn't turn around and knock him out that night.

This run-in with Simpson was one of hundreds of encounters that basketball gave Dabich — a journey that took him from the tiny town of Hudson, Wyoming, and the Wind River Reservation to New York City and Europe and back home again, crossing paths with an impressive list of hoops legends.

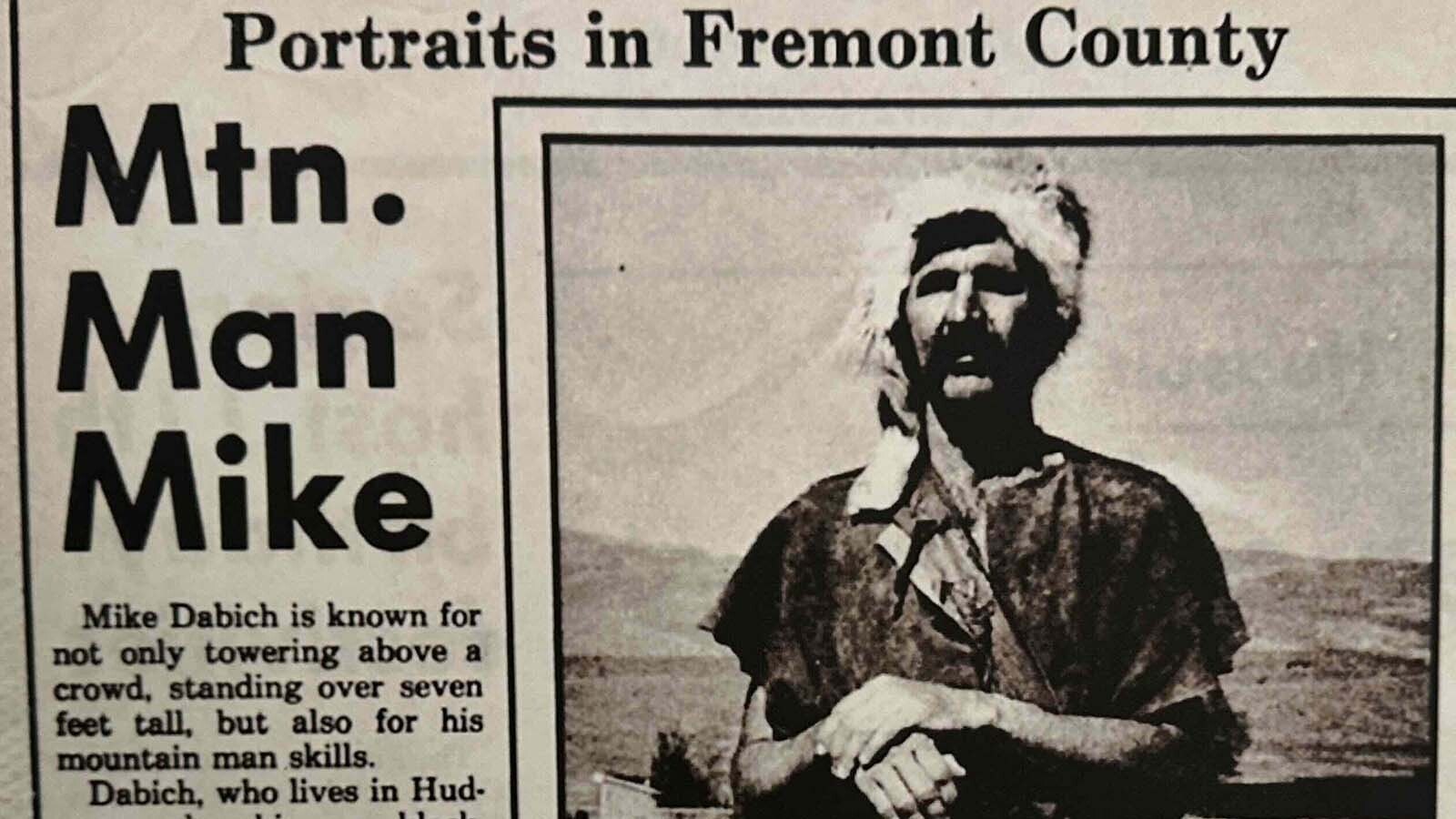

Now 83 and living in Hudson, Dabich enjoys sharing stories from his past and reflecting on what his chosen sport has become. While he holds court at his dining room table, the anecdotes rain down like arching jump shots. Some inspire. Others shock.

When Dabich shares the memorable moments of his life, he uses hands — the size of dinner plates — as he gestures through moves made on the court.

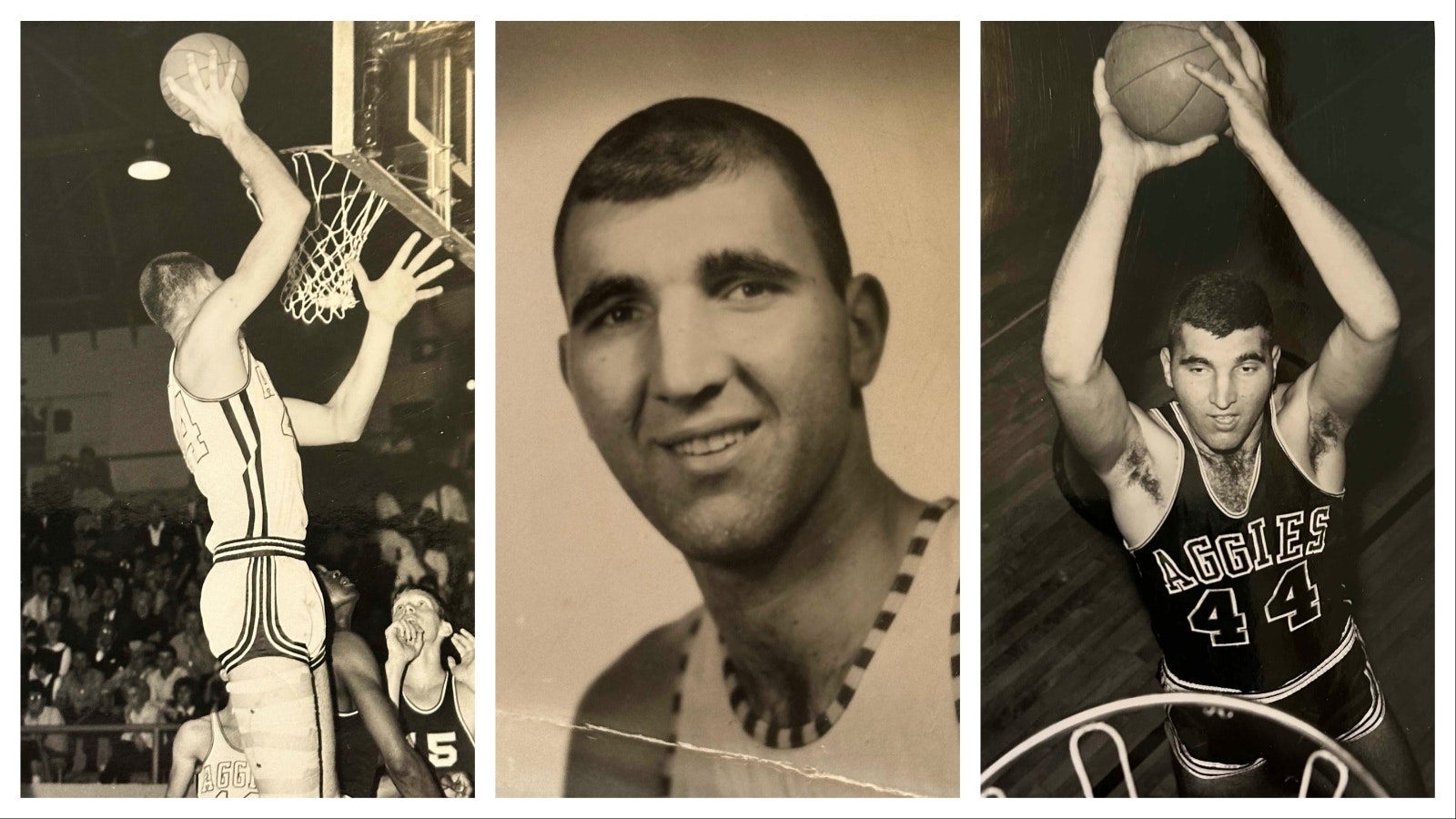

Dabich’s signature shot was the baseline jump hook. It showed off the athletic finesse he developed in high school. Earlier in life, Dabich’s clumsy, lumbering nature earned him his nickname, Moose.

When Dabich was around 12 years old, he crashed through a screen door like a moose barreling through willows: all momentum, no thought for what's in the way.

The nickname stuck among friends in Fremont County, through three different colleges and while playing pro basketball on two continents.

His remarkable height of 7 feet came from his ancestors. His grandfather stood 6-foot-7 and was the shortest of five brothers, four of whom were Orthodox priests. The Slavic gene pool would later produce NBA star Nikola Jokic, possibly the best player in the world.

Rez Ball

Dabich learned basketball by breaking into closed gyms around Lander and playing on the Wind River Reservation alongside some of Wyoming's all-time greatest high school players — Hubert Friday, Alfred Redman, Shannon Brown, Spoon Hunter and Mickey Gamble.

Some of those guys played on dirt courts rutted out by recent rains. Dribbling was nearly impossible. The ball would hit a rut and bounce sideways, skip and die in the dust.

So the Native players became efficient passers running the weave, said Dabich. They avoided dribbling and instead moved the ball hand to hand, always in motion, everyone reading the floor together. No wasted movement, it was pure court vision.

"I played a lot of tournament basketball out there with those guys," Dabich said, who combined his genetic predisposition to height and touch with his lived experience playing on tribal courts where passing beat dribbling every time.

But he also watched his teammates and rivals get punished for speaking their own Native languages, the same way he'd been spanked with a yardstick in first grade for speaking Serbian when his grandfather was still alive. His parents made him stand in the corner.

"Hubert Friday had braids," Dabich remembered. "They cut his braids off and didn’t let him speak Arapaho."

Back then, there was a sign at the Fremont Hotel in downtown Lander that read: "No Indians and dogs allowed."

Lightning And Rattlesnakes

When Dabich was 15, he was out baling hay as a thunderstorm rolled in. He wanted to finish before the rain.

Then lightning hit a fence, traveled to the baler, and knocked him unconscious on the tractor. His father hauled him to an old Army doctor in Lander.

As hard as it was, ranch work was better than the coal mines around Hudson. Down in those shafts, they didn't use canaries to test whether it was safe to enter. They relied on the resident rattlesnakes that lived in the tunnels.

If there were live snakes at the mouth of the mine, it was probably safe to go in. Dead snakes meant bad air, poison gas, no oxygen.

But Dabich had another problem with the mines: he was shooting up too fast to fit in the shafts. From 6-4 to 6-7, then to 6-10 ½ before graduating from high school.

Eventually he topped out at 7 feet.

"I had a lot of joint problems," he said about his height. "My mom was concerned about me and she took me to different doctors to see if there wasn't something wrong with me."

There was nothing wrong. Just a body growing toward basketball, away from the mines and rattlesnakes to a world way bigger than Lander and Hudson.

Three Colleges

In college, he was a journeyman basketball player before transfers were common.

“I was the transfer portal before there was a transfer portal,” joked Dabich.

The University of Wyoming came first. Dabich washed out after one season. He watched Flynn Robinson — a star guard — skip classes and thought he could do the same.

"I wasn't ready, I didn't go to class," he said. "I just washed out."

After one year in Laramie, he was done.

Next came Sheridan College, then Montana State University and finally New Mexico State, where he played with his brother Don.

By then Dabich had stopped growing and was working on his signature move for hours every day, a nice jump hook from the baseline.

His greatest college game came against the legendary Texas Western Miners.

Coach Don Haskins had assembled an all-Black starting five that would win an NCAA championship and break college basketball's most visible color barrier, changing the sport forever.

Against that historic program, Dabich put up 19 points and grabbed 12 rebounds.

"I was the only white guy on the floor" when New Mexico State played Texas Western in Las Cruces, he remembered.

New York Nights

The New York Knicks drafted Dabich in the seventh round in 1966. They already had Willis Reed — the previous year's Rookie of the Year — and Walt Bellamy, the NBA's second-leading scorer.

"How am I going to make the Knicks team, right?" Dabich said. "I didn't have the outside shot that I needed."

The team stayed in a hotel right off Broadway in New York City. Next door, they were performing “Fiddler on the Roof,” which actor Zero Mostel made famous playing Tevye, the Jewish milkman struggling to hold onto tradition in a changing world.

Between practices and shootarounds, Dabich would slip into the empty theater and sit in the back row, listening to rehearsals.

At night, his teammates took him to jazz clubs in the West Village to see Thelonious Monk.

He’d return the favor, eventually taking Willis Reed bow hunting in Wyoming.

Among Legends

At one point in his pro career, a teenaged Bill Walton asked for Dabich’s autograph.

The giants at the time in the pros were Wilt Chamberlain and Bill Russell, and Dabich banged in the paint against both of them.

"Everybody says, ‘Who's the greatest of all time?" Dabich asked. "I don't think there's anybody stronger than Wilt Chamberlain."

He watched Wilt "The Stilt" brush off defenders like they were Lilliputians. And he admired Russell’s clever style and ability to fake out opponents in ways no one in the gym saw coming.

Peacemaker

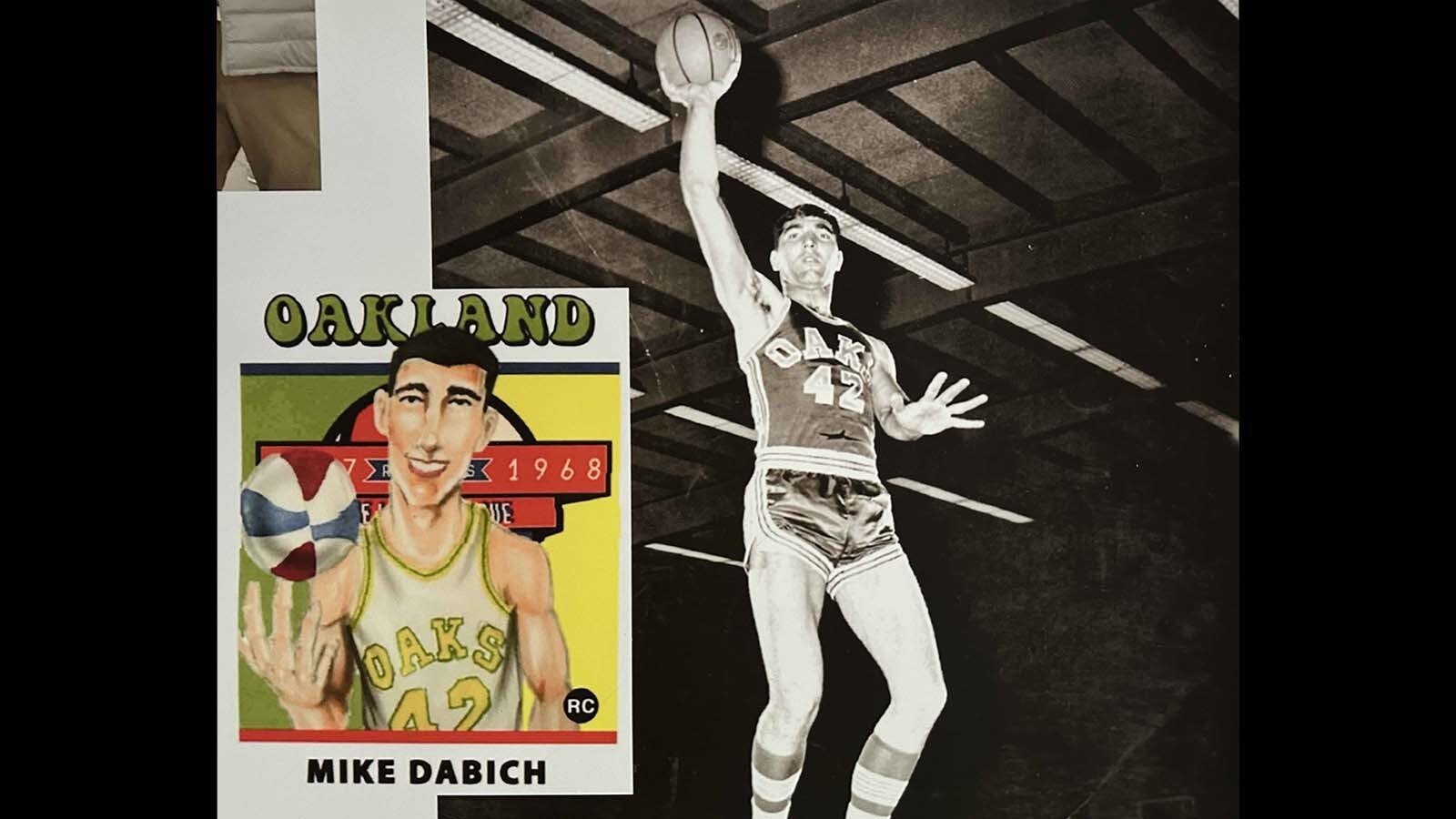

Playing for the old Oakland Oaks, Dabich stepped between Doug Moe and possible death.

At halftime of a game in Denver, Moe — who would later become a popular pro coach famous for his run-and-gun offense and calling players "stiffs" — chased Laverne Tart into the locker room. They'd been trash talking and shoving all game, the tension building with every elbow and push.

Tart dove for his gym bag and came up with a pistol pointed at Moe.

"I grabbed the pistol like that," Dabich explained, motioning with his massive hands how he did it.

Cops arrived. Dabich stuck the gun under his arm until they separated the two players and the officers left.

Players carried guns in those days, said Dabich. They'd board airplanes with firearms tucked in their luggage, and nobody checked.

Dabich said the pro game at that time was rough, violent — a barely controlled chaos. And the money wasn’t great. Dabich's Oakland contract paid $12,000 total for two years.

While in Oakland, Dabich suffered his worst injury.

He jumped so high — that 40-inch vertical that launched all 7 feet of him skyward — that his arm crashed into the corner of the backboard. They didn't have pads back then, and he busted a blood vessel in his arm.

Seated recently in the mid-day light of his dining room, Dabich motioned his arms and tried to recreate the motion that led to the injury.

Poking fun at the sight of his swollen arm, Dabich said, "I looked like Popeye.”

Station Wagon Man

One day in Oakland, Sonny Vaccaro showed up in a Ford station wagon “full of shoes," Dabich remembered.

Vaccaro was driving around giving away free pairs to players, building relationships, getting his brand of the moment — Adidas — on feet.

"I got two pairs of (size) 16s and one pair of 15s. I just took them because he was giving them away," laughed Dabich.

Vaccaro would later recruit Michael Jordan for Nike and launch the modern era of athlete endorsements worth billions of dollars. He’s played by Matt Damon in the film “Air.”

That’s when Dabich could see the business of basketball changing, with money flooding in and the amateur era dying.

"Nowadays, junior high kids can get shoe deals,” said Dabich.

Back Home

By the 1970s, Dabich was ready to settle down in Wyoming, where he became a sheetrocking contractor.

"I was built for it," he said, motioning with his hands, showing how he used to hold up the sheetrock and screw it into the ceiling.

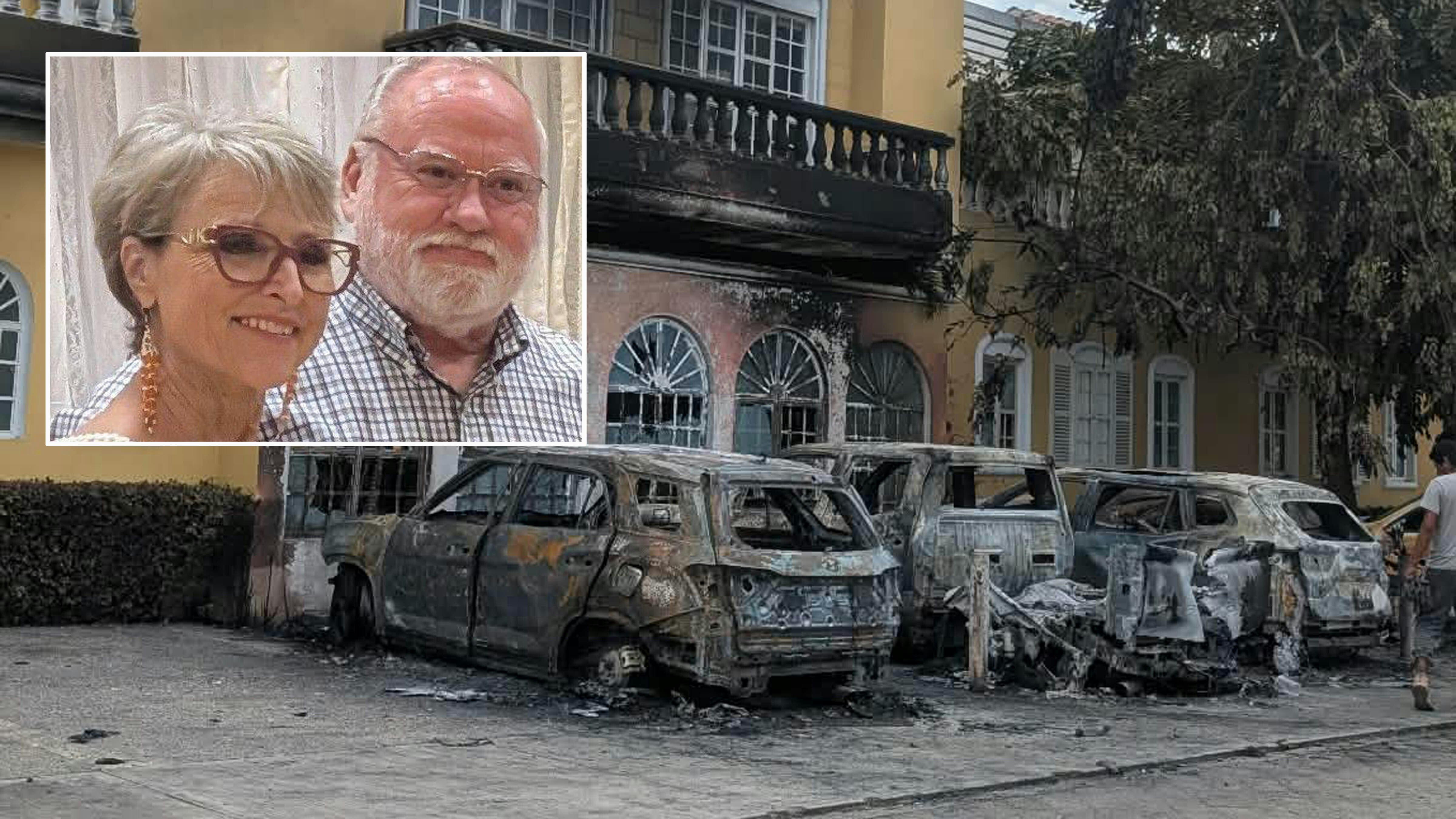

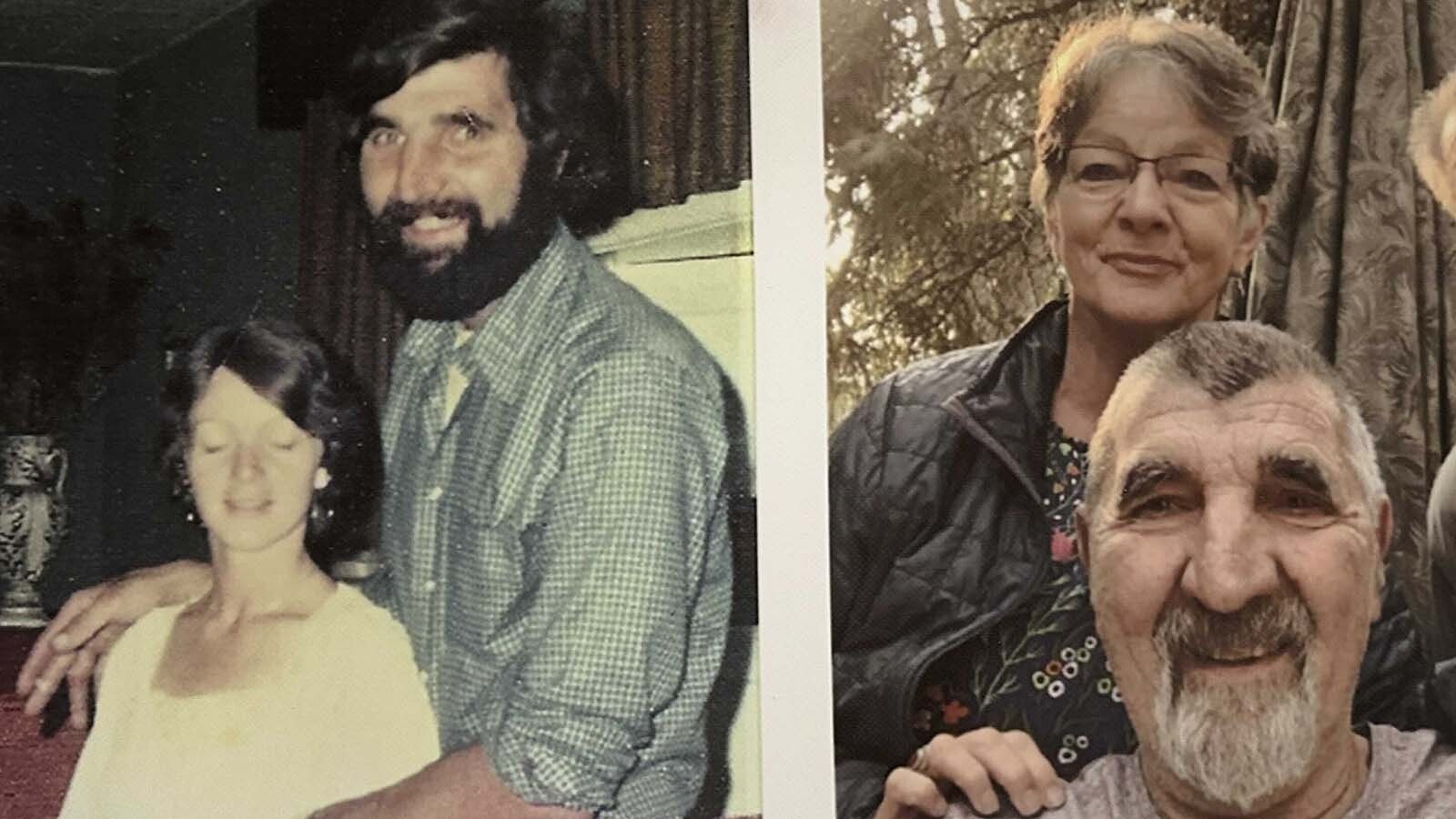

Dabich built his own house, one stick at a time. Never had a mortgage. He started a family with Michaela, and they’ve been married for 55 years.

"Mike is so much more than a basketball player," Michaela interjected, showing off a photo timeline she put together for Dabich’s 80th birthday.

The photos show Dabich’s mountain man phase. A guy offered to teach Dabich how to build muzzleloading rifles. Dabich asked what he owed him.

“And he said, ‘Pass it on.’ So I've helped a couple other guys build rifles and stuff,” he said.

Dabich learned the craft, got deer and elk with his custom-built rifles, and attended rendezvous where mountain men gathered to celebrate the old ways and dress in animal skins.

He also got into building box guitars. He's made several over the years, including one crafted from a hospital bedpan. The metal gave it a unique resonance you can’t get from wood.

Taking Care

Like many his age, Dabich is dealing with some health issues.

He's had three ablations for atrial fibrillation. He asked his cardiologist at Intermountain Heart Rhythm in Salt Lake City if there was any correlation between the lightning strike and the atrial fibrillation?

"He said he didn't know. He said if I wanted to get struck by lightning again, maybe we could see,” laughed Dabich.

These days, Dabich is a big fan of Nikola Jokic on the Denver Nuggets. Moose clearly relates to what he sees on the court — the Slavic height and touch, the all-knowing vision, the self-effacing attitude.

"When he's playing, he's two plays ahead of everybody else," Dabich said. "So smart. His basketball IQ is way up there."

Dabich still shoots around sometimes, sharing anecdotes with his pickup game pals.

So many brushes with greatness, so many good memories. Like that time he shagged free throw balls for legendary sharpshooter Rick Barry, who often shot underhanded.

“I watched him shoot 98 out of 100 underhanded in granny style. He's just making one free throw after another. He said what it did was it opened up his airways when he put his arms down like that,” explained Dabich, remembering how Barry breathed easy and sunk shot after shot.

When asked to describe himself back in those days, at the height of his career, Dabich demurs with a smile, again motioning with those massive hands and insisting, "I never really considered myself a giant."

Contact David Madison at david@cowboystatedaily.com

David Madison can be reached at david@cowboystatedaily.com.