National Geographic asked actor Robert Redford in 1976 to follow in the footsteps of the Wild West's greatest outlaws in a three-week adventure on horseback, by car, and by boat.

It apparently didn't take much convincing because Redford was already in love with the almost too-wild-to-be-true history of the West and Wyoming.

“We tend to view the Western outlaw, rightly or not, as a romantic figure,” Redford later wrote for the magazine. “I know I'm guilty of it, and for years I have been fascinated by that part of the West that offered sanctuary and escape routes to hundreds of colorful, lawless men.”

The Lure Of The Wild West

Before his 1976 trek along a 600-mile stretch of The Outlaw Trail, Redford was already familiar with the wide-open spaces of Wyoming.

He had spent time over the years immersing himself in his breakout roles of both Butch Cassidy and mountain man Jeremiah “Liver-Eating” Johnson.

One of Redford’s first trips to the Cowboy State was in 1967 before he had achieved superstar status.

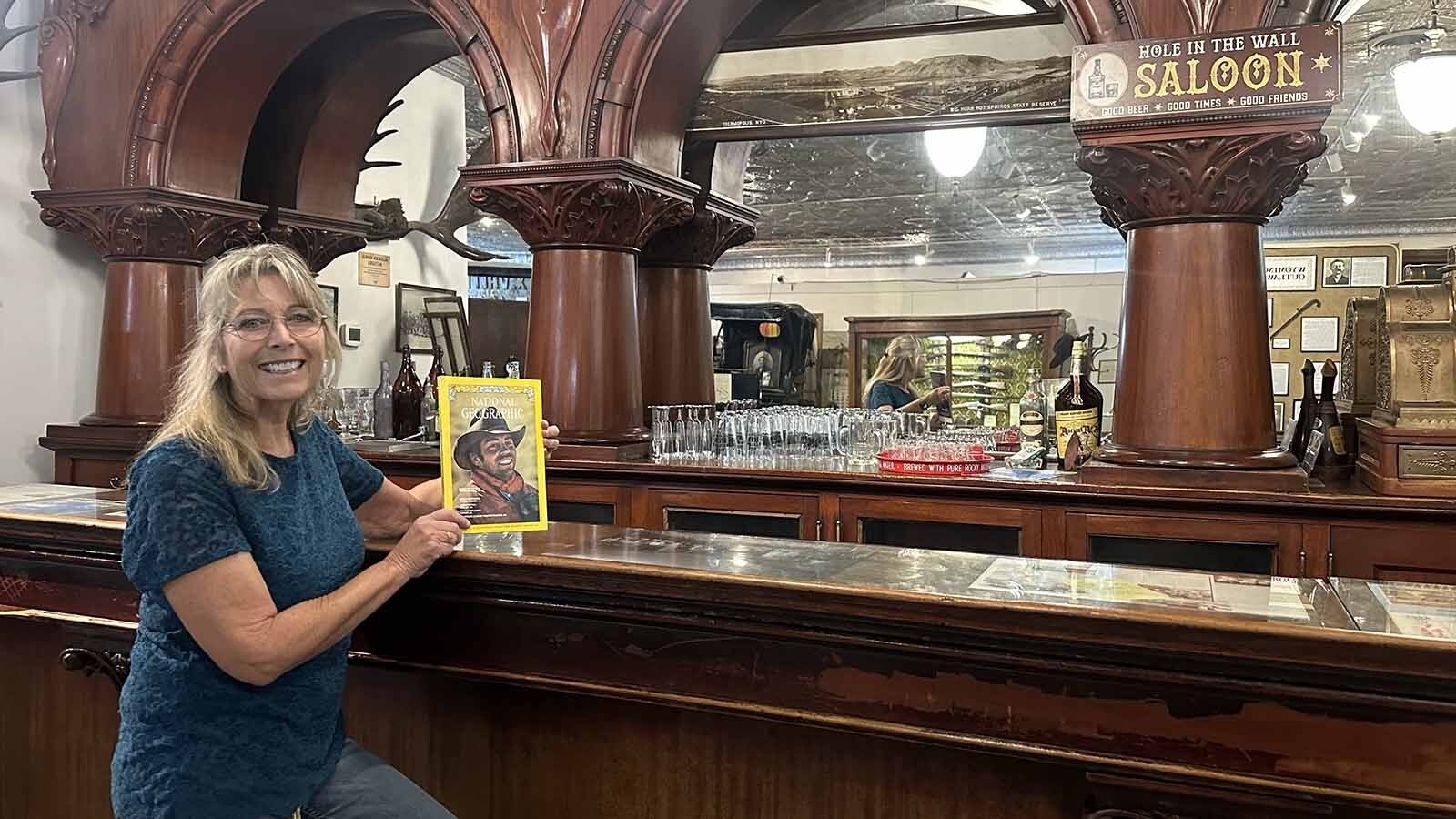

When he stopped at Curtin’s Liquor in Thermopolis, store owner F. W. “Diddy” Curtin just saw him as another lost city slicker exploring Wyoming’s wild past.

Redford was, in fact, looking for a saloon that was still active since the 1890s, which Wyoming outlaws were known to have frequented.

“A well-dressed gentleman came to the store and asked where the Hole in the Wall Bar was,” said John Curtin, Diddy’s son. “Dad pointed it out since it was on the same block.”

When Redford left, Diddy watched him get into a convertible with California license plates.

It wasn’t until the movie “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” came out in 1969 that Diddy realized that the lost Californian was Redford.

The actor was apparently getting into character by exploring Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid's old stomping grounds in and around Thermopolis.

Following The Outlaw Trail

A decade after this scouting trip to Thermopolis, Redford accepted National Geographic's challenge of following the Outlaw Trail with enthusiasm.

He recruited a small team of eight that included a Western historian, photographer and spouse, a marketing consultant and spouse, a naturalist, an artist and the town manager of Vail, Colorado.

Redford’s group all had one thing in common — a deep love of the outdoors and a passion for Western history.

Redford’s eclectic group was to set out on horseback to retrace a 600-mile segment of the historic and often rugged route.

Along the way, they would be joined by cowboys and other interesting characters who would ignite Redford’s imagination.

His resulting article and book captivated people from all over the world and brought Wyoming and the other Western states into the world’s spotlight, even decades later.

“Robert Redford traced the footsteps of the notorious outlaws in the Wild West at the turn of the century,” Celia Andrews wrote for the Western Dail Press in England two years after his trek. “The subject was obviously a crusade to make people realize how rich in history the Western states are, and how soon the remains of the legendary rogues will disappear if neglected.”

Redford wrote that this trail took him to Thermopolis, Shoshoni, Riverton and finally to Lander at the foot of the beautiful Wind River Range.

“Around here, early in his outlaw career, Butch Cassidy had passed himself off as a horse dealer; some noticed, however, that he was always selling, never buying,” Redford wrote. “Kerry Boren, our historian, said Cassidy was supposed to have cached $30,000 in these mountains.”

Cowboy Wisdom

What struck Redford the most were the people he met along the way. Early on the trip, he met the Taylors from Blue Creek Ranch.

"Many people from around here come from outlaw backgrounds," Ethel Taylor, 80, told Redford. "Sometimes they leave mysteriously. We don't ever ask why. We're proud of it."

Tex was one of those outlaws who tended cattle for the Taylors.

He was a grizzled old cowhand that Redford said rode into camp looking as though he had consumed an entire distillery.

He had tangled with a bank clerk in San Antonio in 1927, Redford was told, and fled to Hole in the Wall. Tex had been in the area ever since.

As they sat around a campfire until 1 in the morning, the conversation turned to the growing government intervention and regulation of the West. Redford shared the following conversation flowing around him.

"Gettin' so if you want to spit these days, you need a permit,” one cowboy said.

"Yeah, and you got to dig a hole first."

"They probably got a handbook on that, too — 'How to Dig Your Hole.'"

"I don't need no handbook," rasped Tex, suddenly alive. "My life is a dug hole."

The next morning, eggs were being cooked for breakfast and Tex offered more cowboy wisdom: “The chicken is the only thing we eat before it's born and after it's dead.”

Celebrity Spotting

Redford wasn’t an unknown star during this trip through Wyoming and was by then recognized by locals.

Bill Sniffin was then the young publisher of the Lander Wyoming State Journal at the time and got the scoop that the celebrity was at Baldwin’s, a clothing store in downtown Lander.

“I snuck in there with my camera and he could hardly stand up,” Sniffin said. “He was so exhausted and sweaty and (they) had just ridden their horses a long distance.”

Redford was complaining loudly and Sniffin silently retreated.

“I decided to leave him alone and not try to interview him right then,” Sniffin said. “I was a good guy, but a lousy reporter.”

Redford left town before Sniffin was able to grab his story and headed on to the gold rush town of South Pass, continuing his long journey on The Outlaw Trail.

The Trail Leading To Gold

Outside of Lander, Redford came to what he called the small, all-but-forgotten settlement of Atlantic City, an old gold-mining town.

“A dirt road led us into a cup of a valley where, to our amazement and joy, nothing seemed to have changed for nearly a century,” Redford said. “A few tiny cabins stood like wooden sentries against stark brown-and-white slopes.”

Redford discovered exactly what he was hoping to find, which was a part of the Wild West virtually unchanged.

Historian Boren told Redford that for about 40 years beginning about 1870, the gold towns were in a lawless area where a man with a past or price on his head was free to roam nameless.

This man had to be good with a gun, fast on a horse, and cleverer than the next. On this trail, no holds were barred and old age was a freak condition.

These history stories along the trail came alive not only for Redford, but for his audience in National Geographic.

“The characters Redford unearthed were certainly wild and violent, but that can be said of a lot of the historic heroes the tourists seek over here,” Andrews of Bristol, England, wrote about the renewed interest his expedition had stirred in people from all over the world.

Wyoming’s Outlaws

Redford had been propelled on his 600-mile crusade lured by outlaws.

“I had heard tales of old graves, cabins, caves, saloons, whole towns now untended,” Redford wrote. “I'd heard stories of the outlaw bands and notorious men who rode the trail: the Red Sash gang, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Jesse and Frank James, the McCarty brothers, Matt Warner, Big Nose George Parrott, Nate Champion, Tom Horn, and many others.”

Redford followed the trail to Browns Park, Robbers Roost, and the Little Hole on the Green River, another historic outlaw hideout of the late 1800s.

“Little Hole was also where we filmed the opening sequence of 'Jeremiah Johnson,' so I had a certain nostalgia for the spot,” Redford wrote, pleased to be able to revisit his own old stomping grounds.

The small group continued on to Vernal, Utah, Flaming Gorge, Nine Mile Canyon, and to Dirty Devil River past Hanksville.

Redford noted that Lake Powell was created by the damming of the Colorado River in 1963, and so for a couple of days, his group traveled by boat since this part of The Outlaw Trail was underwater.

Nothing Like The Movies

Redford also discovered that he couldn’t always believe the stories Hollywood told about the Wild West.

In April 1892, Cheyenne cattle barons imported a gang of 20 gunfighters from Texas to rid Wyoming of rustlers and small cattlemen alike in the famous Johnson County War.

The "invaders" were held to a stalemate and it took the U.S. Cavalry to rescue them from a countersiege by a force of irate settlers and outlaws, according to Redford.

“I had read a film script that told of at least 100 people shot in the war,” Redford wrote.

However, when he asked cowboy Garvin Taylor about it, Redford was surprised to learn the Hollywood telling of the story had been more skewed than he had expected to make it more exciting.

"That's a lot of puckie," Taylor said. "Only four was killed. Nate Champion and Nick Ray was ambushed in a cabin right over there."

He pointed to a distant flat.

"One guy shot himself in the foot and got gangrene,” Taylor said. “Another died from something else. But hell, there was more people shot in a poker game in Gillette."

That night, Redford discovered that he had mistakenly brought his son’s sleeping bag and it was too small to stuff himself into.

“I cursed my carelessness and dozed off thinking of the cowboys who spent months like this, back when there were no down sleeping bags, hand warmers, snow boots, or thermal underwear,” Redford said. “I thought about hard ground and hard bones and the saddle for a pillow.”

End Of The Trail

It seemed fitting to Redford that he finished his trail ride at the home of an old friend.

“We celebrated the journey's end with Butch Cassidy's sister, Lula Betenson,” Redford wrote. “She is in her 90s now and living in the nearby town of Circleville, Utah. This would complete our story.”

Betenson and Redford had first met in 1968 when she visited the film set of “Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid,” in which Redford had played The Kid.

“She struck me then as an unusual person. Spry, witty, strong-willed, and with a gentle feminine spirit,” Redford wrote. “Lula was one of 13 children and only a baby when Butch left home.”

Betenson led Redford and his group to the original homestead and cabin she and Butch grew up in. It was late afternoon and a fall breeze was blowing leaves around the cabin.

She and Redford walked along together through the old house and around the land.

She talked of losing sight in her right eye and was starting to lose it in the other. She took hold of Redford’s arm and looked him straight on, leaving him with words that he carried with him long after the trek down The Outlaw Trail had ended.

"I don't mind dying," Betensen told him. "I'm just afraid it won't be soon enough. I'm fightin' the melancholy. Don't like goodbyes. Can't stand 'em. Never used to bother me.”

As Redford looked around, he wrote the final paragraph for his National Geographic assignment and waxed poetic as he noted the end of an era.

“The house is old. Gray-splintered sagging wood. The window frames are bleached. The rooms are small, as in all the buildings of this kind we have visited,” he wrote. “Burglars have looted the original furnishings. Out back are the original corrals, tired and tilted against a background of burnt-yellow and gray hill.”

The Outlaw Trail that pulled on Redford continued to call the actor until his recent death in his Utah home at age 89.

Despite the cold nights, long days in the saddle and only the remnants remaining of the Wild West, through his long trail ride, Redford brought the past alive for himself and an entire generation across the world.

Jackie Dorothy can be reached at jackie@cowboystatedaily.com.