If there were a list of the best Ice Age fossil sites, two that would top the list would be the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, California, and Natural Trap Cave in the Bighorn Mountains near Lovell.

The differences between the sites, however, couldn’t be more prominent.

The La Brea Tar Pits are a 13-acre park with a museum, pedestrian pathways, and attracts more than 350,000 visitors every year. It’s also planning a massive multimillion-dollar transformation that will include a 3,281-foot-long pedestrian walkway.

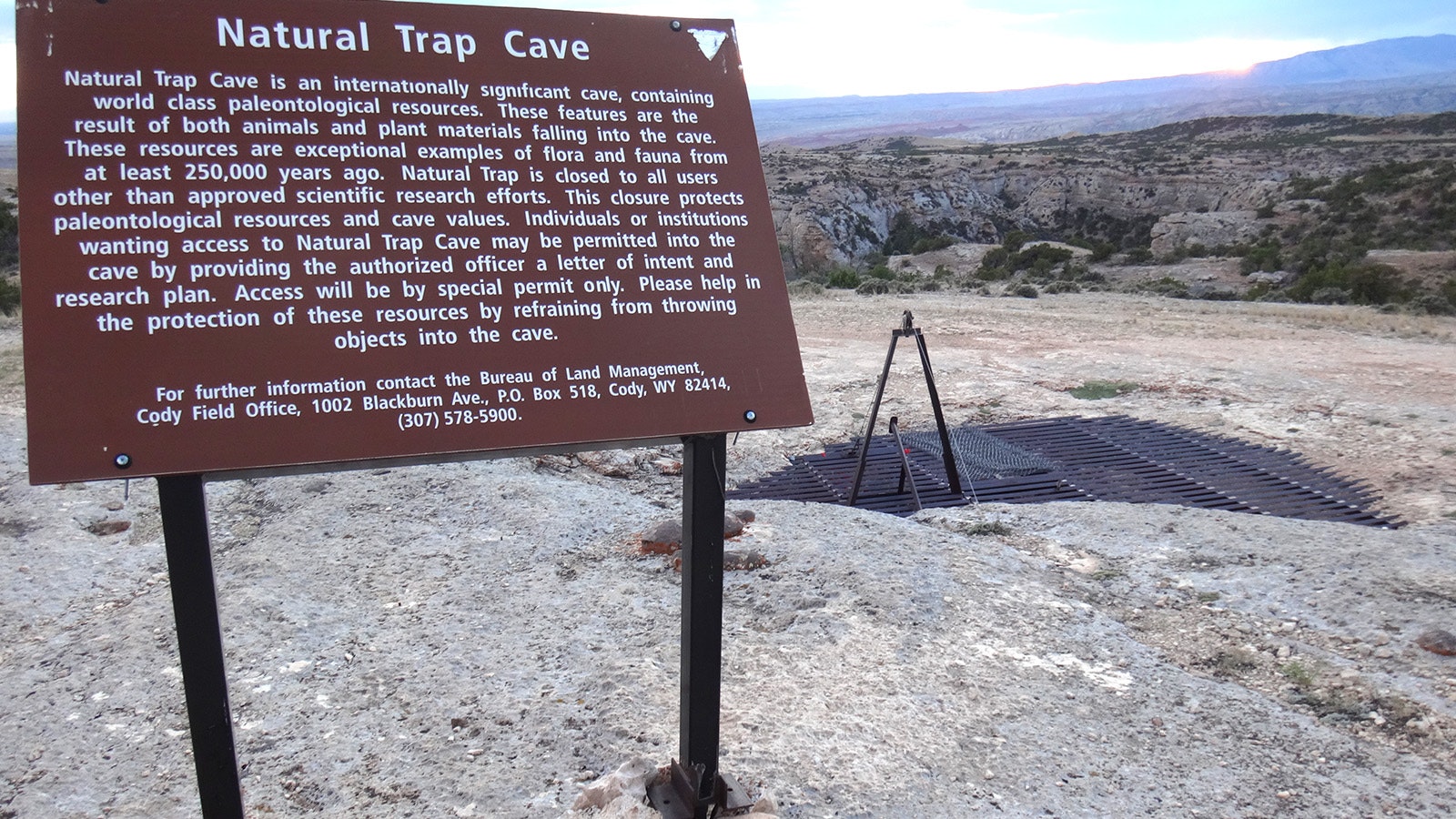

Meanwhile, the only thing that initially stands out about Natural Trap Cave is a heavy metal grate covering the main entry of the 85-foot-deep chasm to keep people and animals from falling inside.

When a team of paleontologists descended into the frigid depths of Natural Trap Cave this summer, a mammoth task awaited them. While poking around in a largely unexplored section of the cave, the excavation team found a large articulated skeleton, with its bones still in their original life position.

“We started digging down in the sediment, and found most of a mammoth,” said Julie Meachen, mammalian biologist and team leader from Des Moines University in Iowa. “We pulled out several vertebrae, a rib or two, and a scapula, and it’s very possible there’s a head buried in the sediment. And they’re big.”

Meachen has been leading students and other scientists down into Natural Trap Cave every summer for 11 years.

It doesn't have the glitz and glamour of the La Brea Tar Pits, but the unique Ice Age site has so many more incredible secrets buried in the cool, moist sediment.

“It’s a hidden gem in a lot of ways,” she said.

All In The Name

The mammoth is just the latest of the incredible discoveries from Natural Trap Cave.

Since the first excavations in 1970, paleontologists have found thousands of remains of dozens of Ice Age animals, unfortunate enough to have plummeted to their deaths at its depths.

The story of Natural Trap Cave is all in its name.

For the last 20,000 years or so, the limestone cave has served as a natural trap for a variety of animals from the Late Pleistocene, including pieces and parts from pikas, rabbits, deer, bison, and bighorn sheep, as well as lions, cheetahs, bears, horses, and mammoths.

In short, it’s a hole in the ground that Ice Age animals kept falling into.

Finding an intact mammoth skeleton is exciting and unusual for Natural Trap Cave. According to Meachen, it's a much larger and more intact discovery than they've come to expect.

“We don't normally find fully articulated animals,” Meachen said. “What we find are isolated elements or a few bones in conjunction with each other.”

For Meachen, the jumbled specimens are evidence that Natural Trap Cave isn’t a closed system. There are active and ongoing processes changing the environment at the bottom of the hole.

“I think whole animals fell into the cave,” she said, “but then processes like water movement in the cave are breaking the bodies apart once they are decomposed. Water, rockfall, and sediments are sliding and moving the bones around.”

That’s why the thick mud is so densely packed with bones, teeth, and other prehistoric pieces and parts. It’s one of the many things that make excavations at Natural Trap Cave so exciting and arduous.

Inching Along (If You're Lucky)

The mammoth, along with all the fossils found at Natural Trap Cave, is buried in a thick layer of moist mud.

When Meachen and her peers excavate these specimens, they must work slowly and with extreme patience to avoid missing or breaking anything.

“When you're excavating something at Natural Trap Cave, there are usually other bones directly under it, behind it, and next to it,” she said. “As you're trying to get a piece out, you realize that it's lying on top of three other pieces, or there’s another bone right next to it. You have to work relatively slowly so you don’t destroy anything.”

Meachen described how they have to “gingerly” remove the hard, moist earth with dental picks and paintbrushes.

Unlike many prehistoric discoveries, which are more rock than bone, the conditions at Natural Trap Cave are unique.

Due to its depth and relative protection from the elements, the temperature at the bottom of the cave remains below 50 degrees with 98% humidity. That means the millennia-old specimens are “fresher” than those at many other fossil sites.

“Some of the bone has been replaced by mineral, but not a lot,” she said. “There are some changes that have happened since the animal fell into the cave, but a lot of the bones have good collagen in them.”

Most fossils have been permineralized, where all the organic elements have been replaced with minerals. The finding of collagen, a structural protein found in bones, cartilage, muscles, and skin, is a sign of excellent preservation with little to no permineralization.

The new mammoth from Natural Trap Cave isn’t as well-preserved as the frozen mammoths from Siberia and Canada, but it’s still primarily composed of bone and collagen rather than rock.

According to Meachen, that makes it an amazing and amazingly delicate discovery.

“We were trying to dig through that clay fast,” she said, “but as soon as you would hit another bone, you'd have to slow down, go back, and figure out what's around it. “You really have to be cognizant of everything that's around the bone when you're doing that excavation.”

Massive, Miniscule, Moldy

There’s so much preserved at Natural Trap Cave that there’s no way to collect everything. Meachen said sometimes they don’t even bother digging by hand.

“We collected a lot of sediment from the cave, which is just the dirt around the bones,” she said. “We did a lot of screenwashing in previous years, and we have got so many small specimens that my colleague, Dr. Jenny McGuire at Georgia Institute of Technology, has in her lab.”

The screenwashing provided McGuire with numerous specimens to study, including tiny bones from mice, prairie dogs, martens, horny toads, and other smaller Late Pleistocene creatures. She also found an American lion claw, a cheetah's toe, and numerous pieces and parts from horses.

A few years ago, Meachen’s team found the nearly complete skeleton of a fox. Rather than excavating those elements individually, they created a plaster jacket to contain the entire specimen – a rare occurrence in Natural Trap Cave.

“The issue with jackets is that they really are time-consuming, and because it's such a high moisture content down there, it takes days and days for the jackets to dry enough for us to get them out,” she said. “We avoid doing the jackets unless we have something incredibly fragile and very valuable.”

Meachen wasn’t screenwashing during this summer’s excavation. Even at Natural Trap Cave, there can be too much of a good thing.

“We're at a breaking point where we have so many (specimens) that we just don't know where to put them all,” she said.

The problem is that specimens from Natural Trap Cave can’t be stored on a shelf indefinitely. Meachen said everything they excavate needs to be dealt with quickly and cleanly.

“All the specimens should be washed and dried immediately,” she said. “That’s simply because the bones have so much moisture in them that if you leave them in their specimen bags too long, they’ll grow mold. They need to be clean and dry before they can be curated.”

So Many Stories

After several decades of collecting, Natural Trap Cave has revealed a treasure trove of Late Pleistocene puzzles for paleontologists to scrutinize.

Meachen’s research, conducted in collaboration with McGuire and Mark Clements from the University of Wyoming, focuses on finding a biological record of Ice Age climate change.

“We’re looking at the long bones and teeth of these mammals to examine wear patterns, get body size estimation, and see if these things change through time and in association with a drying climate,” Meachen said. “We've got a wonderful pollen record, isotopes from the dirt, and bacterial samples that give us a great climate record over the last 30,000 to 50,000 years.

"Now, we want to see if the animals are changing in response to that climate.”

Meachen said pinpointing a “favorite” discovery from Natural Trap Cave was difficult. Ultimately, she decided she was a cat person.

“The American cheetah is a really rare species to find, and we find so many of them in Natural Trap Cave,” she said. “But I'm also a big sucker for American lions. When we find more material from those species, I always enjoy it.”

During the Late Pleistocene, Wyoming could’ve been confused for the Serengeti of Africa. American cheetahs and lions hunted camels, horses, and pronghorn in the shadow of mammoths, mastodons, and the occasional giant ground sloth.

Some of the best specimens of American cheetahs and lions ever found, including articulated and nearly complete skeletons, have been discovered in Natural Trap Cave.

It’s been suggested that large carnivores are overrepresented at the site, which means they might have been lured to and died at the cave while being drawn to the appetizing smell of decaying flesh.

Then there’s “Packy Le Pew,” a packrat that fell into the cave and died during an excavation in Summer 2014. Meachen fashioned a metal cage to put over the packrat so they could observe how its body decomposes.

“He’s in my freezer back in Des Moines,” Meachen said. “Funnily enough, we're a little attached to him.”

A Hybrid Hole In The Bridge

One of the greatest assets of Natural Trap Cave is its location on the North American continent. According to Meachen, Natural Trap existed in a “natural gap” during the Late Pleistocene, which means it got a lot of fornicating foot traffic.

“Natural Trap Cave is in an area that was at the end of the ice-free corridor between two Pleistocene glaciers,” she said. “It was an ice-free corridor between Eurasia and North America. The specific habitat of Natural Trap Cave, and the richness and variety of species, are not found in a lot of other localities.”

Meachen said many of the animals found at the site are hybrids of North American and Eurasian species that came into contact in the glacial gap. Many of them are being studied as new species from a “hybridization zone” that hasn’t been seen anywhere else.

“The amount of hybridization that we find at Natural Trap Cave is actually pretty stunning,” she said. “We found it in several species already, and many of these aren't even published. Some of them are in the process of getting published. This site is super unique for that.”

Sharing The Spotlight

Natural Trap Cave doesn't have anything close to the same level of fame and visitation as the La Brea Tar Pits. Outside of Meachen and her team, nobody’s allowed inside, and there isn't an on-site museum sharing its story.

“The original exhibits for Natural Trap Cave were at the Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum at the University of Kansas, and there weren’t a lot of them,” she said. “That's so far removed from the actual site that I don't think it has the same punch if you're in Wyoming.”

The disparity between these two sites, with equally incredible Ice Age discoveries, speaks to the differences between California and Wyoming. However, Meachen believes her work has increased the visibility and notoriety of Natural Trap Cave.

More scientists are taking an interest in what can be learned from the discoveries at Natural Trap Cave, particularly in the context of genetic research.

Due to the cave’s consistently cool and moist conditions, many bones have preserved mitochondrial DNA from the Ice Age, which has been used to help reconstruct the genomes of extinct animals.

There will never be a multi-million-dollar museum campus for Natural Trap Cave, but La Brea can hog the Hollywood spotlight. Meachen, who's worked extensively at both sites, has a more modest idea on how to properly showcase the incredible discoveries she and her peers have made.

“I've been working with the folks at the University of Wyoming Geological Museum about making an exhibit on Natural Trap Cave,” she said. “I think that would be great, because that museum does quite a lot of Wyoming visitors, and it would be wonderful if we could showcase that Wyoming site to people who live in Wyoming.”

Meachen added that all the specimens she’s excavated from Natural Trap Cave over the last decade will be permanently housed at the University of Wyoming.

The mammoths, lions, and cheetahs might have migrated to the opposite end of Wyoming, but they’ll have a permanent home there.

Passing The Torch

For the last 11 years, Meachen has been coordinating with her peers, Bighorn National Forest, and other agencies to continue descending into and excavating incredible things out of Natural Trap Cave. That made this summer’s trip a little bittersweet.

“This was my last year at Natural Trap as the team leader,” she said. “There's absolutely nothing negative I have to say about the cave, but doing all the logistical planning for the summer field season is such hard work. So, I’m letting it go and moving on.”

Meachen is training John Jacisin, a “newly minted” assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, to take up the torch and become the new team leader. She’d still like to continue working at Natural Trap Cave, but her 11 seasons of excavating have provided enough research to last a lifetime.

“I'm not done working on the site yet,” she said. “There's still lots of science to be done. I’d just like to enjoy more of my summer and not feel like the weight of the world is on my shoulders every time I go out there.”

Regardless of who takes up her torch, Meachen is sure that there’s plenty more to find at Natural Trap Cave. Setting aside the rest of the mammoth that’s still buried and waiting, the potential of this unique Ice Age site is limitless.

“The cave never disappoints,” she said. “I think my legacy will always be on the cave, because of all the amazing work that we've done over the last 11 years, but it’s always productive.

"And just because I've given up leading the excavations does not mean I've given up working on the science at Natural Trap Cave.”

Andrew Rossi can be reached at arossi@cowboystatedaily.com.