In October 1899, the peace in the frontier town of Glenrock, Wyoming, was destroyed with a single gunshot.

The window of the post office was shattered and James Barker, a local coal miner and former deputy sheriff, slumped to the ground at the feet of his wife.

He was mortally wounded, and the only suspect was the local blacksmith, John Blessing.

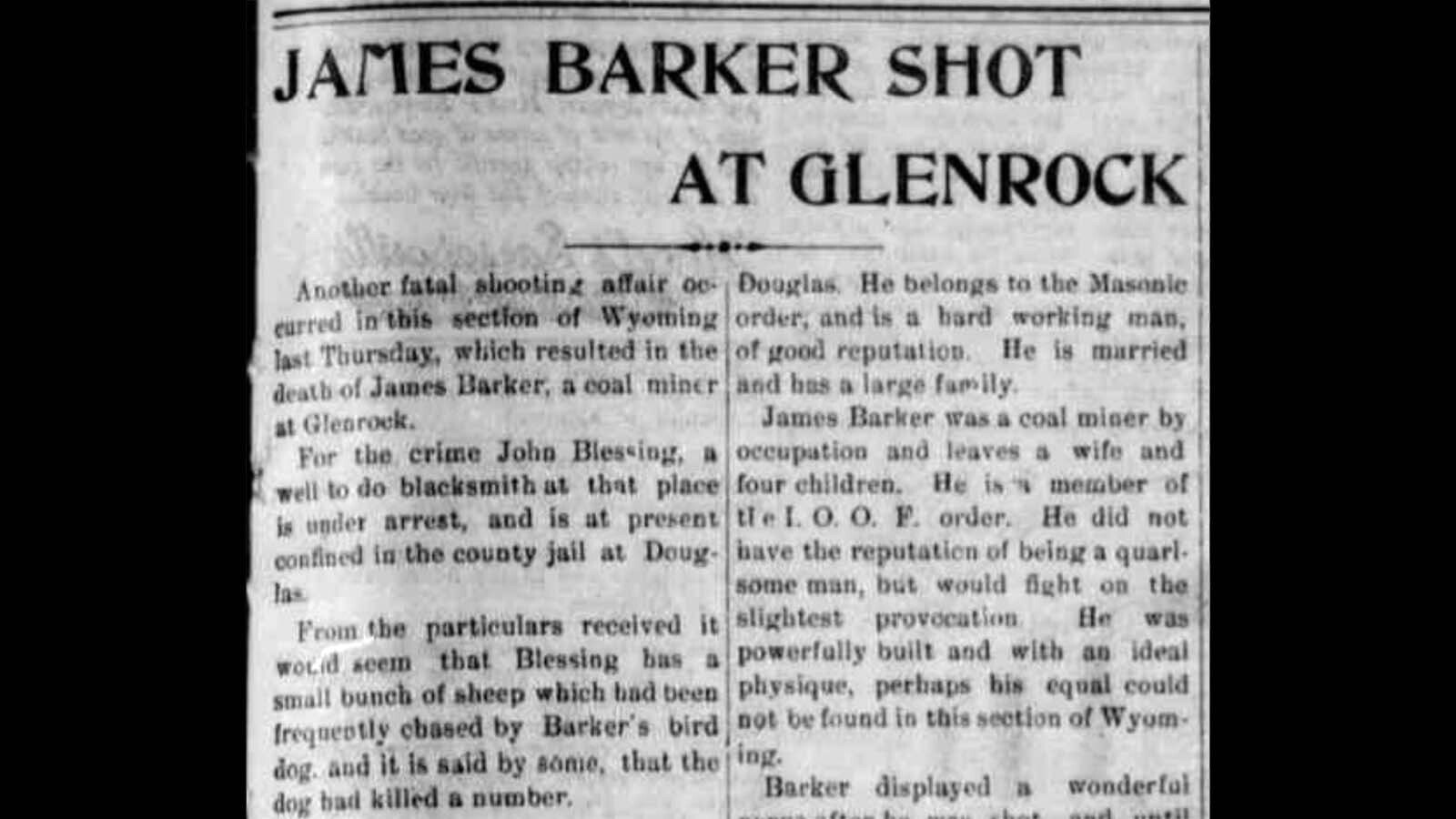

Within days, The Natrona County Tribune and other papers reported the story in every lurid detail, immediately defending the accused murderer. The press and the Freemasons rallied around Blessing, claiming he was too good of a citizen to have shot Barker in cold blood.

This cold-blooded murder caused an uproar in Glenrock.

Most of the townsfolk also sided with Blessing and denied that it was he who killed Barker. When it looked like Blessing was going to be acquitted, the coal miners who worked with Barker were outraged.

It was the Freemasons against the coal miners, Barker’s wife, Dora Barker McGrath, later recalled in an interview with the Thermopolis Independent Record in 1948.

McGrath said that the majority of the townspeople maintained vigorously that Blessing would never be convicted for, as they boasted: “Masons never hang.”

It was this boast the coal miners were determined to prove a lie.

Four hundred miners from the local coal mine prepared to march into Douglas. They rallied behind their spokesman who declared that they were going to hang the murderer themselves. They would let the end of a rope prove his guilt once and for all.

The Murdered Coal Miner

The victim James Barker had arrived in Wyoming about 14 years earlier as a soldier stationed at Fort Fetterman and his wife, Dora, later joined him with their small daughter.

After he was discharged, Barker began working at the coal mines and eventually became the foreman. He was later appointed as a deputy sheriff by Sheriff Malcomb Campbell.

By 1891, the Bill Barlow’s Budget was complaining that Barker was being overpaid with his salary of $40 a month as a deputy sheriff. Thus, by the end of the year, he left his badge behind and was back at the coal mines.

The couple was well-liked in their circle of friends and family and would host events for the local town such as ice-skating parties on their pond.

In June 1899, the Converse County Herald of Lusk had reported that Barker was fixing up a very nice little home on his five acres near town. He had quite a lot of fruit trees and bushes bearing fruit that year.

By the time of the murder, the couple had four children, ranging from a 13-year-old daughter to a 6-year-old son. With Barker’s job at the mines and their tiny homestead thriving, life was looking bright for the family.

Except for the children’s barking dog.

The Fight With The Neighbor

John Blessing, the local blacksmith, ran sheep within his enclosed field that was near to town, neighboring the Barker’s own parcel.

Reports varied with the Barkers saying the dog was merely barking at the sheep while Blessing claimed that the dog was much more dangerous.

The Natrona County Tribune reported that Barker’s dog kept chasing and harassing sheep.

Blessing pleaded with Barker and Barker’s friends to take care of the dog, the Tribune reported, but on the day of the murder, Blessing saw the dog again chasing his stock and ordered a man who was working for him to take a shot at the dog with a shotgun as the animal was running away.

The Tribune claimed that the dog returned home hit with a few shots but was practically uninjured.

Barker was furious because, as McGrath later said, there was no conclusive evidence of the dog’s guilt.

That night, about 8 p.m., Barker and his wife rode into town to pick up their mail. Blessing was there as well, and the Tribune said that Barker called out Blessing for shooting his children’s dog. Heated words were exchanged by both sides.

A fight ensued.

“The blacksmith was assaulted by the coal miner, knocked down several times and severely kicked and beaten,” the Tribune said. “Blessing got up and as he started off called Barker a cowardly ****, and said that he would make him eat it before he slept.”

Another report said that bystanders rushed to Blessing’s rescue. Blessing then staggered home, about an eighth of a mile away.

Murder

After Blessing left the area, Barker and his wife went into the post office, which was run by Dora’s brother-in-law, Dr. F.C. Rugg.

The Wyoming Derrick reported that about fifteen minutes later, Barker was standing in the back portion of the post office building, in one of the rooms used as a residence by the postmaster.

Barker was reading a letter, and back of him with her hand on his shoulder, his wife was standing looking over his shoulder.

Suddenly, a shot was fired through the kitchen window.

The street was full of people at the time of the murder, but no eyewitnesses would admit to seeing anyone.

If Blessing had returned, the Natrona Tribune said, he would have had to cross the main street twice on coming and going, yet no one saw him.

As Barker lay dying, his small family gathered around him and he was said to have displayed a “wonderful nerve.”

“When told by Dr. Hoff that he had to die, he took it calmly, almost as though it concerned some other than himself,” the Tribune reported. “He bid his wife, children and friends goodbye as though he was going on a short journey, soon to return.”

Barker had been shot on Thursday and by Saturday, he was gone.

The Tribune detailed the damage done to Barker from the bullet for its readers.

Evidently a bullet from a .45 caliber revolver, had passed through the back portion of Barker’s right arm, missed the bone, then struck the sixth rib, passing through the back portion of the right lung, entering the spinal column lacerating the posterior portion of the spinal cord, and embedding itself in the opposite portion of the spinal column from which it had entered.

The entire lower portion of Barker’s body had been paralyzed from the time of the shooting, and the right lung was found to be collapsed and full of blood.

Friends Quick To Defend

The press and most of the residents of Glenrock rallied around Blessing, claiming that he was the honorable man, not Barker.

Despite their protests of his innocence, Blessing was arrested and placed in the county jail at Douglas.

The press in Wyoming continued to praise Blessing and said that he could not have murdered Barker in cold blood.

“He belongs to the Masonic order, and is a hardworking man of good reputation,” the Wyoming Derrick said in his defense.

“He is a sober, steady, temperate, quiet citizen, one of the best in Wyoming,” the Natrona County Tribune said. “No unlawful act was ever before charged against him. He has always been regarded as a model man and citizen in every respect, who has no known enemies and deserved none.”

On the other hand, the papers carried descriptions of the murder victim that were less than flattering.

“Barker was a quarrelsome bully, who has pounded up a good many people, been in jail several times and is trouble of some sort most of the time,” the Natrona County Tribune reported. “That he must ultimately meet with some such fate as finally did befall him was only a question of times.”

The reporter opined that Barker had left behind his wife who was well respected and a large family of children who she now must care for alone because of her husband’s misdeeds.

“Barker is a member of IOOF,” the Wyoming Derrick reported. “He did not have the reputation of being a quarrelsome man but would fight on the slightest provocation. He was powerfully built and with an ideal physique, perhaps his equal would not be found in this section of Wyoming.”

Jury By Press And Public Opinion

It was no secret that the majority of Glenrock’s citizens believed Blessing to be innocent and that Barker had been killed by an “unknown” assailant. Half the town went to the preliminary hearing held the next month in Douglas.

When the bail was set, they apparently pooled their resources together and Blessing was allowed to return home.

“The required bond was only $20,000, but had it been $200,000, the bond would have furnished without delay,” the Tribune wrote. “Although the testimony against Mr. Blessing was of such a nature that it was necessary to hold him for trial in the district court, his attorneys claim that it was impossible for the defendant to have committed the crime under the circumstances, and they will have no trouble in proving this when the case comes up for trial.”

The reporter claimed that the sentiment in Glenrock seemed to be very largely in Mr. Blessing’s favor and that there seemed to be no question, but that Blessing would be acquitted of the crime charged against him.

Mob Lynching

The coal miners whom Barker had worked with for nearly two decades, realized that the Freemasons had rigged the courts.

They saw this as a miscarriage of justice that they could not just sit idly by and watch happen.

Organizing themselves into a mob, four hundred workers rallied together, determined that the murderer would pay for his crime with his own life.

Dora, now a young widow just barely in her 30s, begged them not to take the law into their own hands. She convinced them that revenge would not bring her husband back and would only bring suffering to them and their families.

Reluctantly, they listened and returned to their homes.

By May, their prediction had come true and Blessing was acquitted. However, he left town immediately and Dora was convinced that he had been prevailed upon to leave under pressure.

After quelling the riot and burying her husband, she was left to support her four young children. With few options, Dora moved in with her parents and helped her mother run a boarding house.

Even though she knew it was for the best not to take justice into their own hands and was glad she was able to stop the lynching, Dora Barker McGrath would forever remember how the coal miners had honored her husband by forming a mob to avenge his death.

Jackie Dorothy can be reached at jackie@cowboystatedaily.com.