Since its invention, carbonated, sweetened soft drinks have exploded in popularity. Sweet, fizzy and oh so quenching.

What’s not to like?

As Americans, we guzzle more than our share. The latest Gallup poll shows about half of us drink a soft drink daily. And those who do consume an average of two and a half bottles or cans a day.

We’re not the only ones with a hankering for these beverages. Hungary is thirsty for pop like no other country, slurping 310 liters of soda per person each year.

The U.S. ranks fourth, by the way.

But this isn’t a story about soft drinks. It’s about what we all call them and why.

So, pop a top, pour a can of bubbly over some ice and let’s get down to some serious soda pop semantics.

It’s The Real Thing

Look, we all know the average bottle of Coke contains enough sugar to dissolve a Dodge Ram pickup in three hours.

But no other beverage pairs as well with a picnic hotdog as a root beer, or cuts through the butter on movie theatre popcorn better than an Orange Sunkist.

Even wine-snobbery rules apply in the carbonated sweetened soft drink world.

Your brown pops go with red meat like hamburgers and jumbo franks. White varietals only — like Sprite and 7UP — with chicken nuggets or fish sticks.

Anything goes, of course, when slaking a pizza thirst.

And just like the affected snootiness that comes inherent with ordering vino at your finer establishments — defined by a sit-down experience where the cutlery is not plastic, crayons are not a “starter” and wine is not poured from a box — one does not like to look a fool.

Know your terminology and proper pronunciation.

Cabernets, pinots (there are two kinds), merlots and shiraz.

It’s a lot to remember, and any linguistic slip up threatens to out a customer as, gasp, some kind of rube.

Pop Or Soda?

The stakes are not quite as high in the soft drink realm but there are subtle distinctions that say a lot about a consumer beginning with the obvious: is it pop or soda?

Or a combo of the two, soda pop?

Then to throw a wrench in the whole discussion, there’s always the defiant Deep South that insists on calling all soft drinks “coke” — a generic reference to anything sweet and fizzy from Dr. Pepper to Diet Pepsi.

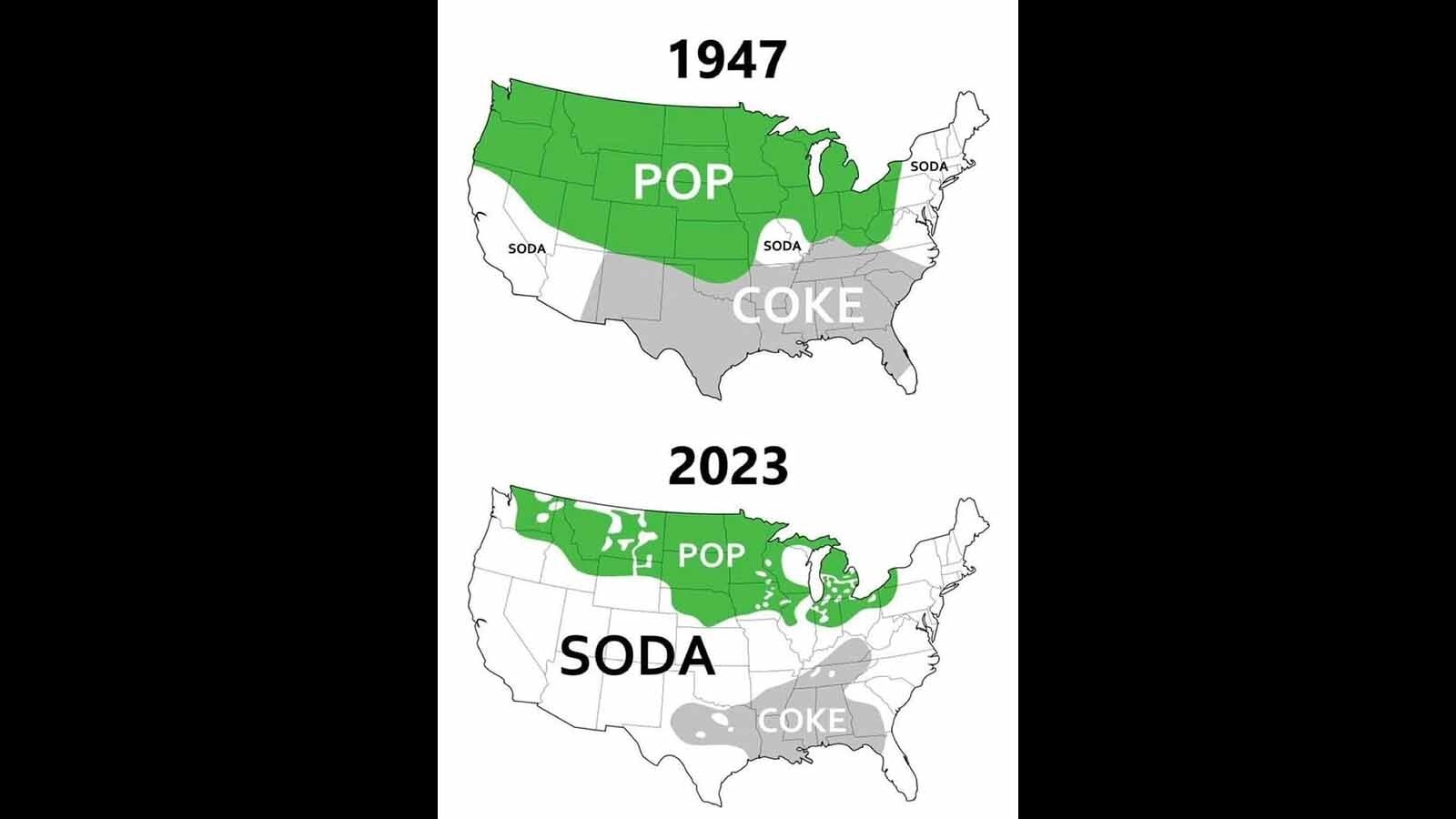

It has been described as a regional thing.

“Soda” is used to refer to fizzy, sugary soft drinks on either coast and in most metropolitan areas, as if there were a type of cosmopolitan enlightenment at play.

In the Midwest and other more rural areas of the U.S., “pop” is the preferred nomenclature.

In the former Confederacy, though observably on the decline, the term “coke” refers to any and all cold drinks with the exception of sweet tea, which is in a league all its own in the South.

For Caryl Simpson, it’s always coke.

She’s from Oklahoma and the wife of longtime newspaperman and Cowboy State Daily contributor Dave Simpson.

Caryl might invite you out for a coke, but that could mean anything.

“Even if you drink Dr. Pepper or Pepsi or coffee, it’s, ‘Let’s meet for a coke,’” she said. “Oh, and our son works for Coke. We are not allowed to go to any restaurant that doesn’t serve Coke.”

What’s In A Name?

First, a shallow dive into the etymology of soda, pop, and soda pop.

Way back in the day, when Napoleon was warring in France, and Lewis and Clark were nearly back in St. Louis from their historic two-year trek across the Louisiana Purchase, a Yale chemistry professor invented the soda fountain.

Benjamin Sillman set up the first such soda fountain in a drugstore in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1806. Even though he was a learned chemist, people would go on to call him a jerk.

On a sidenote, it was also that spring when future president Andrew Jackson shot a hole in Charles Dickinson, killing the rival graveyard dead in a duel.

Perhaps he celebrated with his second by clinking pop bottles and taking a big gulp. You’d have to ask Jackson whether he called the victory drink pop or soda.

Americans quickly developed a taste for bubbly beverages.

By the middle of the century, pharmacists were expounding on the carbonated concoctions, adding various roots and fruits, often marketing the drinks as tonics that could cure of everything from fatigue to flatulence.

Sassafras (origin of root beer) was soon followed by Vernors Ginger Ale (1866), Dr. Pepper (1885), Coca-Cola (1886) and Pepsi-Cola (1898).

Before even Stillman’s first soda fountain, Joseph Priestley had perfected the process of carbonation in 1767. By 1783, Schweppes marketed its carbonated mineral water.

Just ahead of the turn of the 20th century, the soda pop era was in full swig.

Why Where Matters

Soda makes sense.

These early fizzy drinks were often infused with salts. Many bodies of water in the West are named “Soda Lake” for their alkaline features rife with dissolved sodium carbonates.

It is presumed pop was added to the back end of soda simply for the sound it makes when a bottle is cracked open. At least that’s the best linguistic historians have come up with.

The first verified use of pop can be found in 1812.

British poet Robert Southey wrote: “A new beverage that is called pop, because pop goes the cork when it is drawn.”

It is interesting to note, however, that soda pop was not bottled for the masses until the 1860s. That coincides perfectly with the popularity of the term pop taking over.

The common belief is soda hung on in the northeast primarily because most soft drinks were still consumed at soda fountains.

In the Midwest, where a glass bottle was the prevailing conveyance, pop began to take over the lexicon.

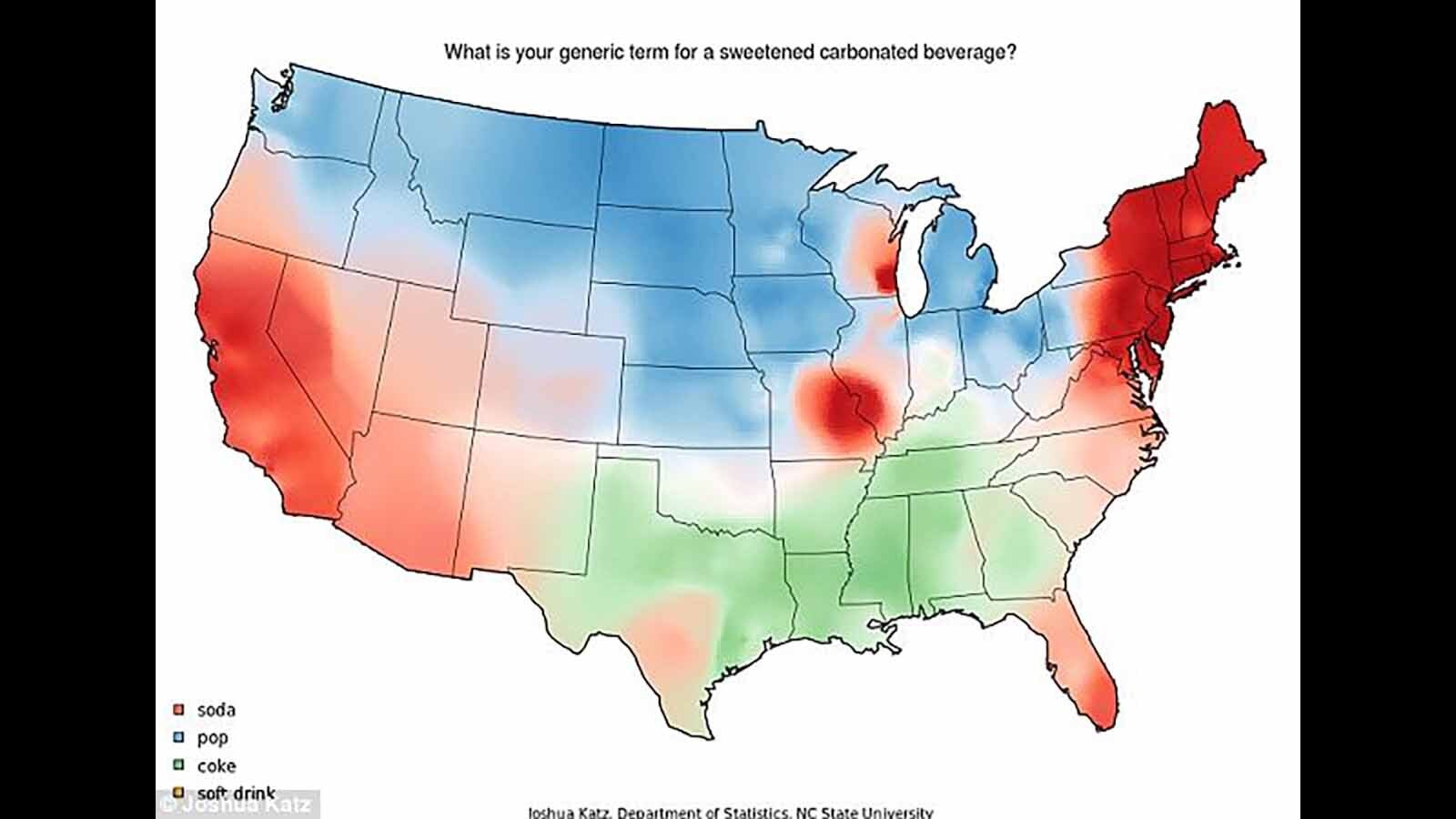

A more detailed map from MapPorn breaks down by state how most refer to their soft drinks. Wyoming is listed as a state where either soda or pop works on a regular basis when ordering at a restaurant.

Head south, though, particularly in Texas, and you’ll likely hear something completely different.

Patron: “We’ll both have cokes.

Server: “What kind?”

Patron: “Pepsi for me and a Canada Dry for the little lady.”

Throughout the south, coke is used as a generic reference to any soft drink. Similar to a proprietary eponym like Kleenex, coke has simply become the term for soda or pop.

Sussing out that derivation, the Coca-Cola Co. is the likely culprit. It was founded and headquartered in Atlanta, and its influence on southerners cannot be overstated.

It’s not all geography. Calling soft drinks soda or pop is also a bit of a sophistication thing.

Kids at the playground in Oshkosh are going to pester mom for a pop.

Try ordering a Schweppervescence at a swank, New England high-society soiree using the word pop. Jeeves will throw you out on your tux tail.

As we age and refine, we tend toward soda. Some of us, anyway.

Many contacted for this story admitted to starting with pop as a kid and graduating to a more enlightened use of soda as they grew more worldly.

Do We Say Soda Or Pop?

Speaking of polling, we used a sample size comprised exclusively of Cowboy State Daily reporters. After all, for journalists, words carry extra meaning.

We asked what they called soft drinks, where they are from and whether they have changed over the years.

Iowa-born Bill Sniffin said it’s “pop all the way.”

Homegrown Wyomingite Gail Symons has always called it soda.

Jen Kocher prefers soda but admits the family back in Ohio says pop.

Born and raised in Colorado, Justin George has always used pop as have his parents. Even two decades living on the East Coast did not sway him to use the word soda.

Fremont County girl Clair McFarland says soda and pop are used interchangeably in her household.

For Mark Heinz, who spent his formulative years in the Rocky Mountain West, it has always been pop. Ditto lifelong westerner Anna-Louise Jackson.

“I call it pop, always have,” Todd Titus agreed. Though he did notice away at college at Notre Dame, more people said soda.

Piper Fennimore exhibited a classic New England approach.

“Growing up in Connecticut, it was always soda. Not pop, not coke — unless you meant an actual Coca-Cola,” Fennimore shared.

“If someone asked for a ‘pop,’ we’d assume they were either from the Midwest or asking for their dad. It’s one of those regional things you don’t realize is weird until you leave.”

Newest Cowboy State Daily hire Jackson Walker was 100% on brand with the accepted historical linguistic narrative.

“I grew up near Appleton, Wisconsin, and my parents and I all refer to a soft drink as soda,” he said. “I recall meeting a few people from northern Wisconsin or the UP of Michigan who would call it pop, and this was very strange to us. We would laugh at anyone who did this.”

And just to complete the trifecta, Jackson said he has a grandmother from Tennessee who called everything coke.

Changes As You Grow

Wendy Corr backed the notion there is a learning curve to personal jargon.

“When I was a kid, it was pop. As I got older, maybe around college, I transitioned to calling it soda,” Corr said.

Sean Barry took a different path with a fond recollection of Mountain Dew.

“Remember those ‘Give me a Dew’ commercials from the ’80s? Those ads look like my teen years in rural northern California when many of us drank Mountain Dew,” Barry said.

“Other than that, I usually just use the generic coke for any soft drink.”

Columnist and attorney Tom Lubnau said he doesn’t fit in either category, but rather encapsulates both.

“My father was from Michigan. My mother was from California. We grew up calling it ‘soda pop,’” he said.

Fellow columnist and attorney Cassie Craven also admitted to shortening her grandparents’ “soda pop fountain” to simply pop in her upbringing.

Jimmy Orr, co-founder and executive editor at Cowboy State Daily has lived everywhere — Wyoming, Colorado, California, Washington, D.C., Boston and St. Louis. Growing up in Cheyenne, he always said pop.

“The whole family called it pop. Never even heard of soda,” he said. “But after moving around the country a lot, for some reason I now call everything coke. And I don’t even drink Coke. I am loyal to Pepsi.

“I have no idea how I picked it up. But that’s what I call it now and I find it very odd.”

For Renee Jean, it’s more than just terminology oddity. Learning not everyone talks the same was eye-opening.

“The first time I recall learning that there were different names for soda was in high school during play practice. Our director had called it pop and some of us kids had no idea what he meant,” she said. “That led to a discussion about how many different names the beverage has, with various people weighing in with names they’ve heard, like ‘coke.’

“I still remember that conversation because it was kind of a first glimpse at a much larger world than the tiny, population 2,000 town I grew up in. There was a whole wide world out there, and there were viewpoints about the most common and ordinary of things that I’d never considered.

“It’s part of why I became a reporter. To discover all those different viewpoints and things of which I had no idea.”

It’s Personal

This topic may never go flat.

What and why we call our soft drinks is important enough to warrant several social studies through the years. One real-time ongoing Pop vs. Soda poll displays a map based on data submission.

The most definitive and oft-cited research is the 2002 work of Matthew Campbell and professor Greg Plumb of East Central University in Oklahoma.

It produced a useful map: “The great ‘pop’ vs. ‘soda’ controversy.”

That work was followed up and mostly confirmed by a paper (“A Linguistic Study: ‘Soda’ and ‘Pop’ in Wisconsin and Minnesota [2007]“) authored by Heidi Sleep and Katie Thiel, undergraduate students at University of Wisconsin-Stout.

The great debate rages on, its significance ranking right up there with what we call a big sandwich: Sub, hero, hoagie, grinder, Dagwood?

Uh oh. We might need a follow up.

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.