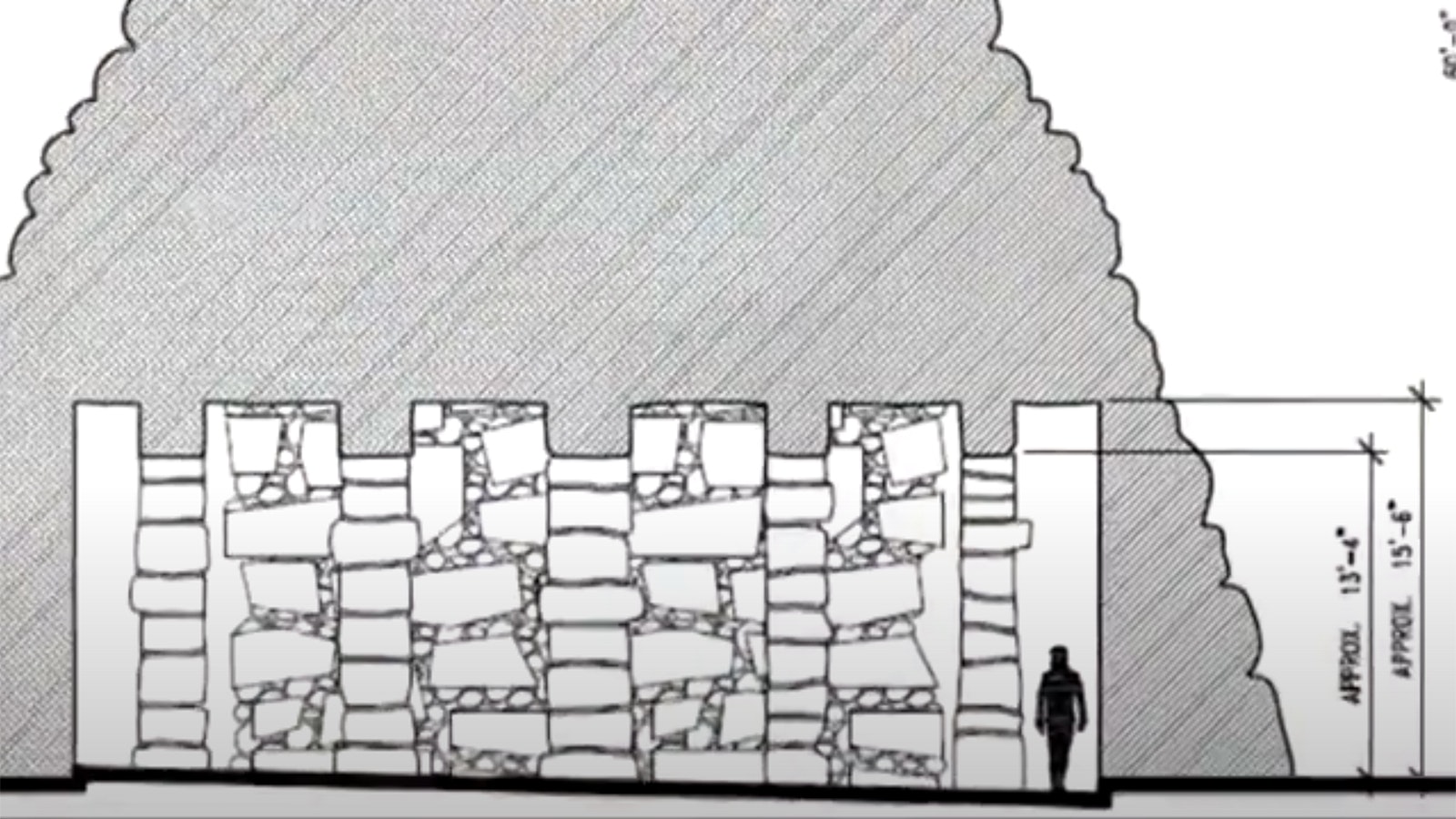

Rising out of rich pastureland in southeastern Wyoming, a 60-foot-high pyramid known as the Ames Monument is “an architectural oddity even many Wyomingites know little about,” according to Wyoming State Parks.

The pyramid was built from massive granite blocks and completed in 1882 to honor Oakes and Oliver Ames, key dealmakers in the completion of the first transcontinental railroad.

It was strategically located to attract eyeballs on high ground near the Union Pacific Railroad line in Albany County.

But in an ironic twist of fate, the Union Pacific line was relocated, leaving the monumental honor to these railroad power brokers out of sight and mind.

While visitors can still find it by following monument signs on Interstate 80 at Exit 329, there is one secretive aspect of this granite stone pyramid they’ll likely never see — the hidden tunnels inside.

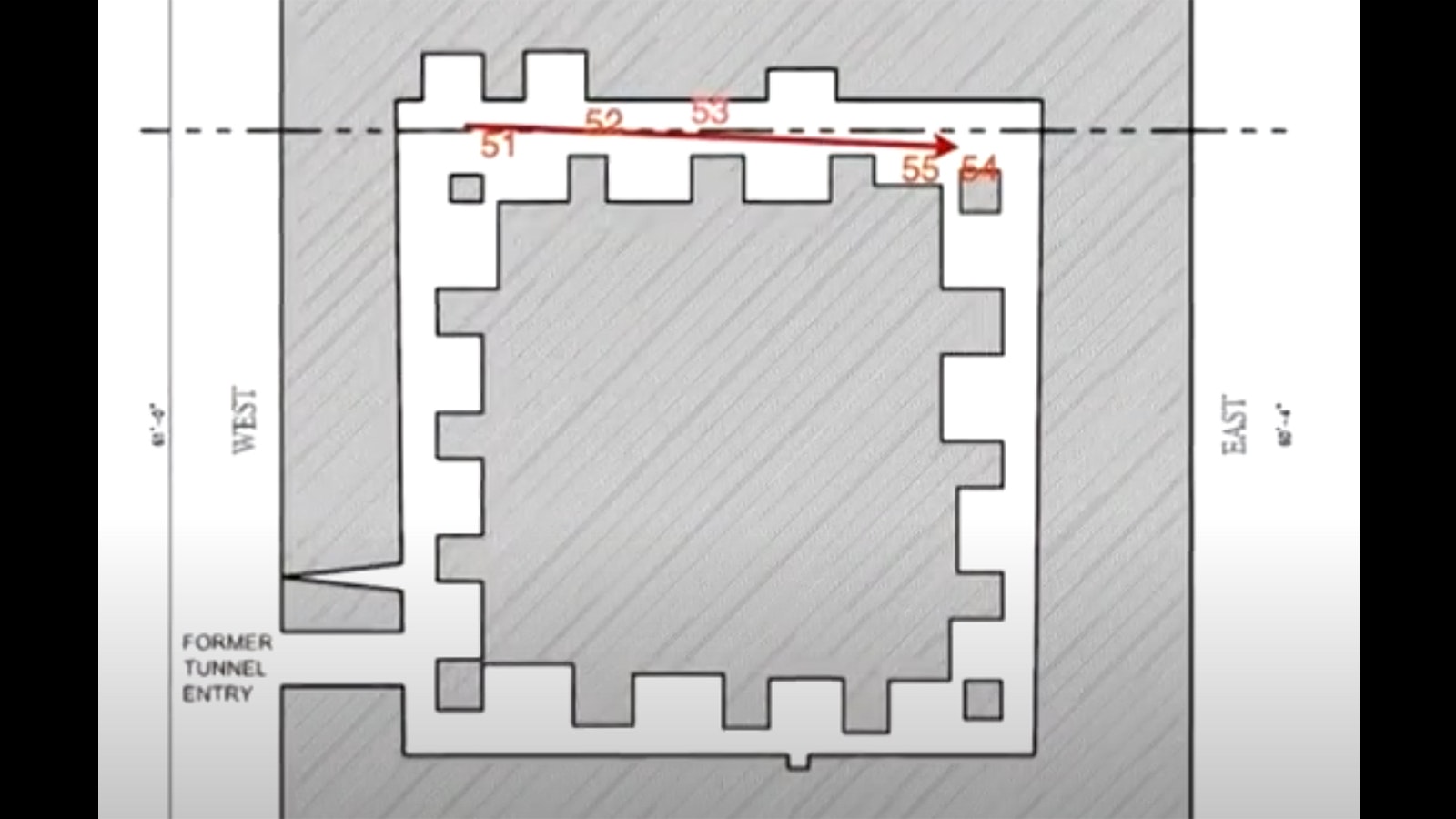

Similar to the pyramids of Egypt, the Ames Monument contains inner passages that have been sealed up, on two separate occasions. The last time anyone bore witness to the inner monument was November 2010, when state officials opened a passage for one day only.

It’s been sealed up since, and it will likely be generations before anyone steps foot inside again.

There is a dwindling number of people with a personal memory of the monument’s interior. One of those people shares their experience here.

Anna Lee Ames

Anna Lee Ames Robinson, 81, is a direct descendent of Oakes Ames. For many years, she pushed for the promotion of the Ames Monument to the status of National Historic Landmark.

The problem was that there needed to be a detailed accounting of its interior first, and the state was reluctant to cooperate, Robinson said.

For many years in the past, an external opening allowed passersby to crawl into the monument, which is said to have as many as four separate levels.

“I’ve met a number of people in who say they remember going inside the monument when they were little kids,” Robinson said. “And they say, ‘I’m not going to tell you what I did in there.’”

Whatever those folk were up to, the state wasn’t fond of it, and in the mid 1980s, officials closed off access to the interior using explosives.

It might have remained closed were it not for Robinson.

Opened For One Day

After years of prodding, politicking and agreeing to underwrite the cost of reopening a workman’s tunnel, the state agreed to give Robinson and a select number of architects and historians an opportunity to go inside.

The plan was put in place. She got a call on the evening of Halloween 2010 and was told that the following day — and the following day only — the Ames Monument would be opened for documentation.

Excavators removed a marble block to an old workman's tunnel, giving Ames and others enough space to belly crawl into the cavity. Robinson was in her 60s at the time, and says she was the most junior member of the team.

“It was hard and only a few of us did it. We had to raise an arm and leg on one side, and then the arm and leg on the other side and slowly push yourselves forward,” she said. “It felt like we were crawling forever.”

At last into the tunnel proper, the team encountered an obstructing block that had fallen from a higher level, likely from the explosive closure in the 1980s. Once they climbed over the rock, they could traverse the tunnel that ran along the outer wall.

Inside, someone had scratched into a rock the phrase, “Drive your car.”

“Who knows what they used to do there. I’m sure they had beer parties and a lot of fun,” she said.

High above where that phrase was notched, in the rock ceiling 16 feet up she noticed a small square opening into the layer above.

“We had no way of getting a ladder in there and not enough time, so we don’t know what it was like. But there’s at least three levels and probably four,” she said.

Though she couldn’t explore to her heart's content, that day was among the happiest in her life.

“I was high as a kite,” Robinson said. “It was one of the high points of my life, because I had worked so hard to get permission to get in there.”

It would take another seven years before it was awarded National Historic Monument designation.

Both the Ames’ family and the State Historical Society held large parties to honor the moment. Robinson paid an actor to portray Abraham Lincoln for the occasion.

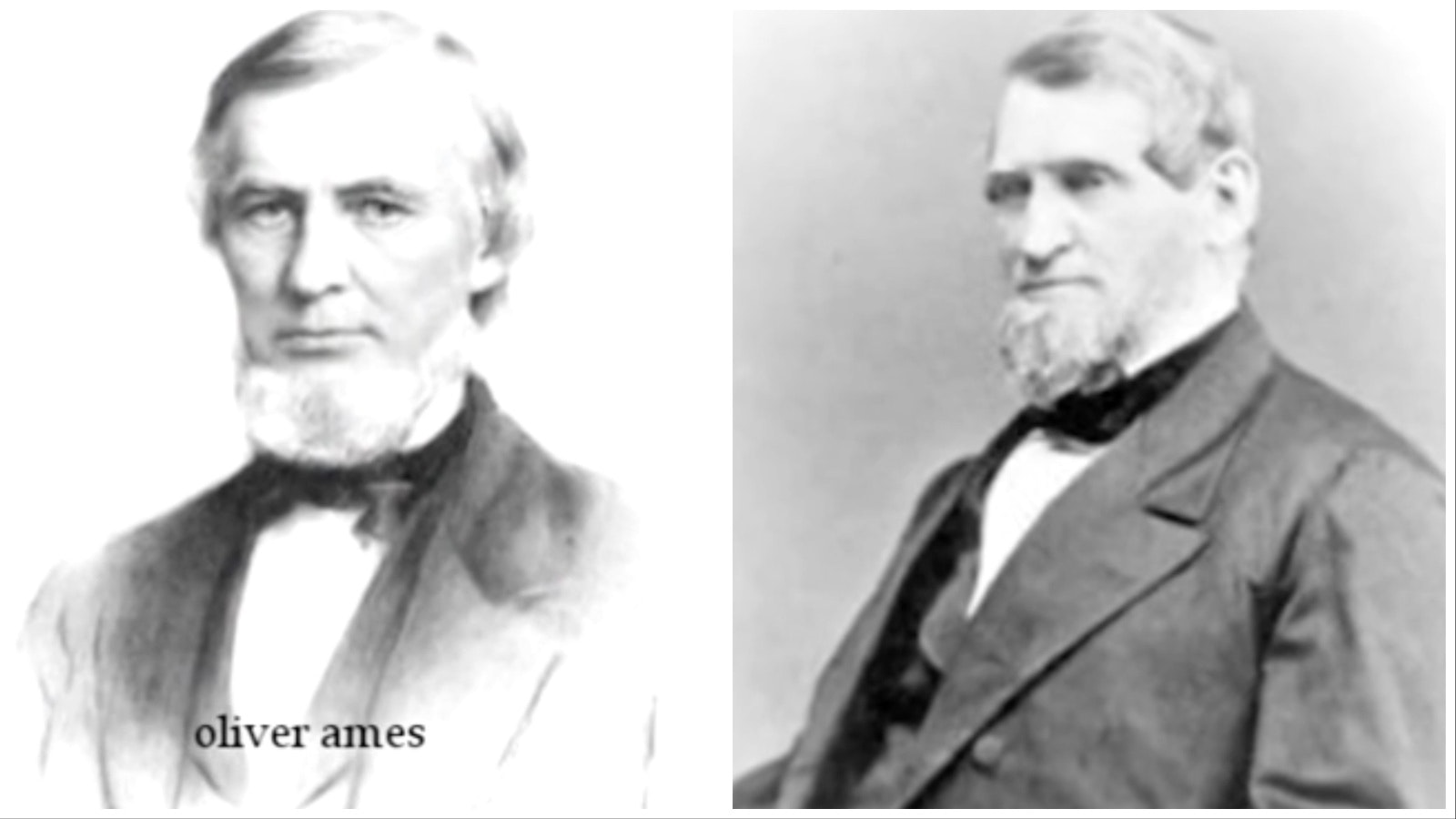

Oakes Ames

Oakes Ames was a Massachusetts congressman and owner of the Ames Shovel Co., which briefly accounted for as much as 80% of the world's shovel sales, according to Robinson.

Ames, along with a myriad of congressional members, would become embroiled in the Credit Mobilier scandal, a scheme in which Union Pacific and Credit Mobilier were purported to have overcharged the federal government for railroad construction; with similar people and interest controlling both companies, they were accused of inflating construction costs.

Robinson, however, asserts that her forebears’ name was falsely maligned, and that it was he himself who hemorrhaged money in an effort to see the transcontinental line completed.

One state historian put his losses at $1 million. Robinson said they were as high as $8 million, citing troves of personally accumulated documentation.

“Eight million dollars in 1869 was plenty,” she said.

As for the moment, Robinson may be the last woman of this century, potentially many more after that, to experience the inner chambers of the Ames Monument.

“This time when they closed it, they really did it, they really gummed it up,” she said. “I’m sorry, but you're not going to be able to go inside, ever.”

Contact Zakary Sonntage at zakary@cowboystatedaily.com

Zakary Sonntag can be reached at zakary@cowboystatedaily.com.