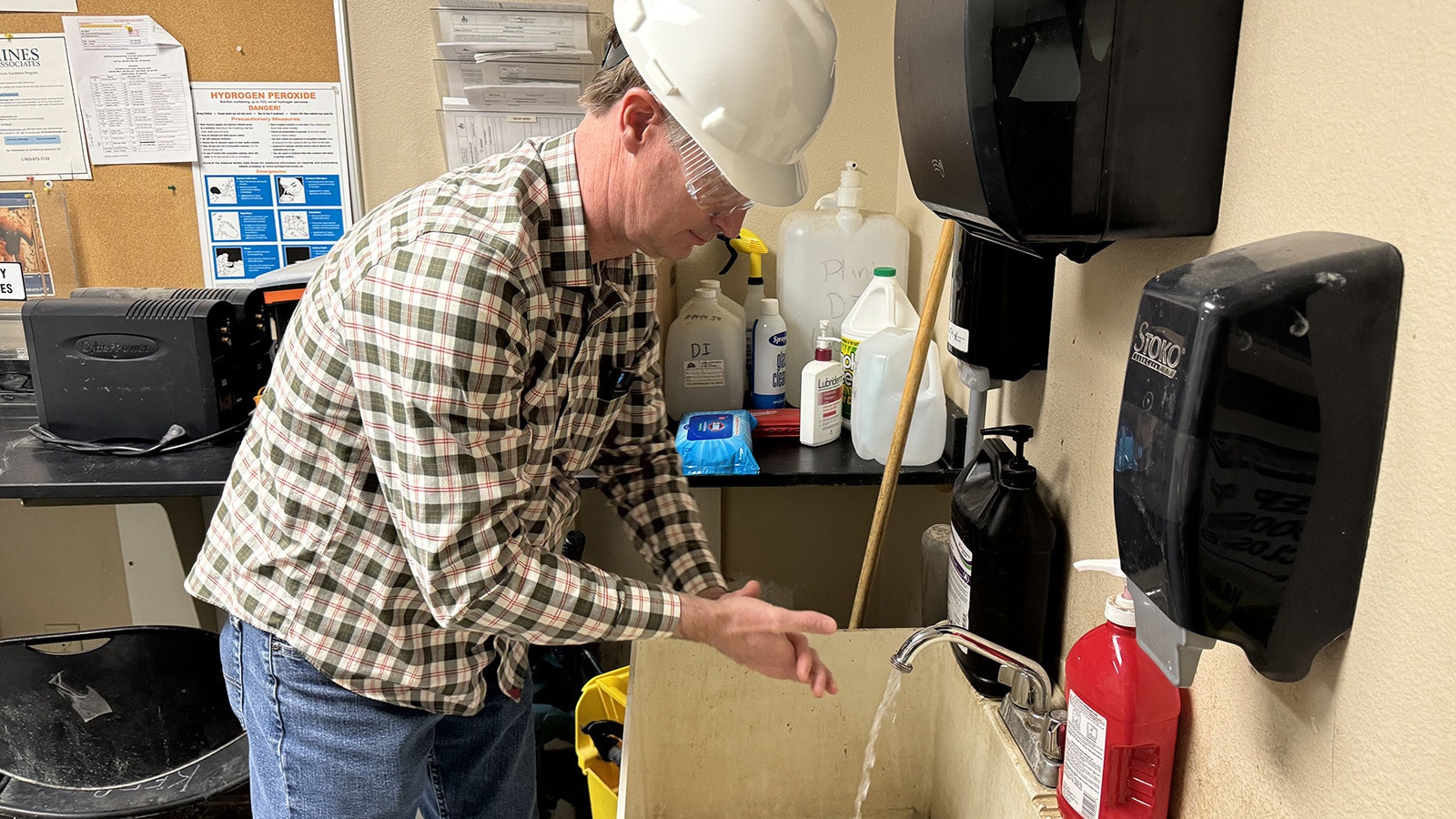

LOST CREEK — John Cash, CEO of Ur-Energy Inc., leaned over the sink at his uranium production plant in the Wyoming Red Desert and squirted red detergent onto his hands and began vigorously scrubbing.

When done, he hit the button on the wall dispenser with his elbow carefully to get a foot-long tear of paper towel.

He dried his hands — between the fingers, palms and back of hands — then waved a Geiger counter baton over his hands and bottoms of his shoes.

Clean. No alarm bell sounded.

It may seem like overkill, but Cash said washing hands at the uranium production site is no joke.

“We live in an ocean of radiation,” Cash said.

The Geiger counter is an electronic device that can read radiation levels, and there’s lots of it around the Lost Creek area, which is rich in underground uranium deposits deep below southcentral Wyoming.

The handwashing ritual is an important one at this uranium oasis where about 60 workers carpool in from Rawlins, Casper, Lander, Riverton and elsewhere.

And there’s plenty of handwashing to do at Lost Creek, the nation’s largest producer of uranium. The operation produced 22,278 pounds of uranium concentrate in 2023, according to the federal Energy Information Administration.

Overall, Wyoming dominates this sector, producing all but 2,672 of the 49,619 pounds mined last year in the United States.

From Ground To Yellowcake

The mining operation at Lost Creek is really all about drilling with water derricks, not oil, that can go down 450 feet into a bed of porous sandstone where there’s a thick 100-foot layer of uranium deposits to tap.

This week, an army of roughnecks were seen running the rigs out near the production plant, which is where other workers run chemicals through a process to strip the uranium out of the dirt.

There are more than 300 drill holes, many with well caps, throughout the mining area.

Clearly visible beside the holes are 6-foot-high, cone-shaped mounds where a backhoe has carved out a rectangular-shaped hole in the ground to store water needed in the drilling process.

A network of water lines crisscrosses the landscape to send water out to 13 rigs, then return a slurry with particles of uranium in the non-potable water to the production plant, where the uranium is turned into yellowcake, a type of uranium concentrate powder.

Bentonite clay, also mined in Wyoming, is used to help with the drilling, keeping the walls of the drill hole from collapsing.

“You got to go where god put the mineral,” Cash said.

The entire process isn’t a simple one. Carbon dioxide is injected into the well as part of an orchestrated mining process called “in-situ” recovery mining.

In-situ is a Latin phrase meaning “on-site” or “in position,” and is standard industry parlance for a kind of mining that relies on pumping water into the ground, then pumping it back to the surface with the ore particles spiraling around in the water.

The entire production line to mine uranium is monitored closely.

All the workers at Lost Creek — including Cash, production plant workers, roughnecks, and white-collar office people — get tested for radiation exposure, Cash said.

“We are very deliberate where we step and what we do. There’s no smoking allowed or eating food in the field,” he said of the dusty environment. “We emphasize good hygiene.”

Everyone is encouraged to wear cotton fiber clothing — no polyesters or nylons, as they attract radiation — and steel-toe boots.

Land Of Lincoln

The production plant is where the magic happens.

The production plant’s end-product is yellowcake powder, stored in 55-gallon drums on the floor of the factory behind a roll-down garage door.

The yellowcake is the uranium company’s gold, and it’s locked away in this basketball court-sized room.

Hydrochloric acid dissolves the uranium in the baking of the uranium, with salt water used to flush the uranium off resin beads used to collect the ore in a flushing process.

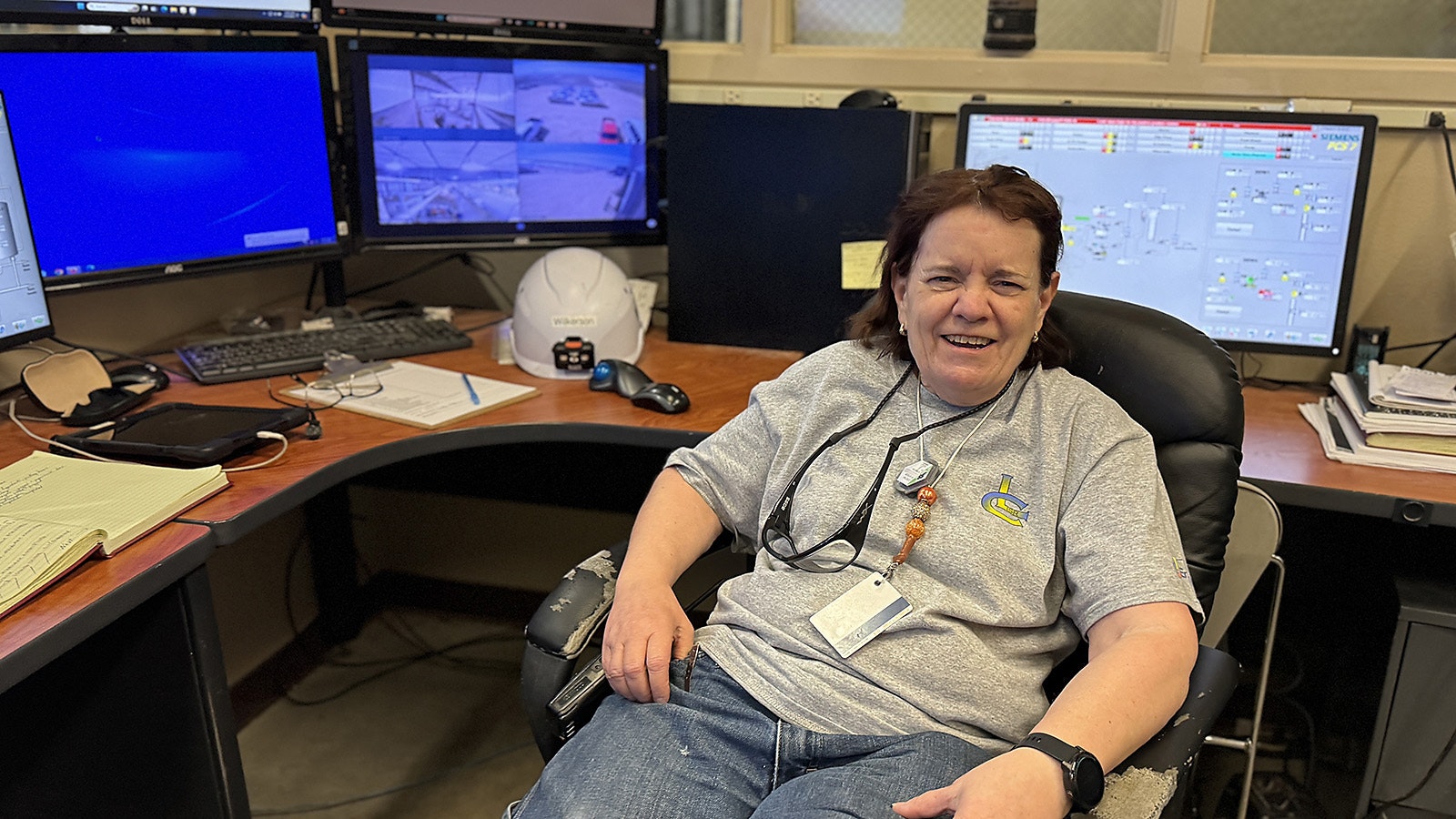

Dorothy Wilkerson, the plant operator, sits in a control room in the production facility surrounded by computer screens, monitoring all the fluid flows and pressures in the pipelines throughout the entire operation.

“The job is critical,” Wilkerson said. “A drop in flows and pressures would indicate a possible water line break.”

After the plant makes yellowcake, the product is transported by truck over 1,300 miles to Metropolis, Illinois, for further processing into nuclear fuel for the nation’s nuclear power plants.

The Illinois location is a collecting point for all mined uranium from Ur-Energy, and really all of Wyoming and elsewhere.

This Illinois factory that handles the uranium conversion process into nuclear fuel is part of a critical industry that has been jolted over the years by geopolitics, decades of falling demand for uranium (until the Russia invasion of Ukraine reversed that trend), and the Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan back in 2011, which temporarily put the brakes on the industry.

Amid seismic concerns raised by Fukushima, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission closed the factory down briefly for a year in 2012 to conduct inspections and require upgrades to improve resilience to natural disasters.

Fueled Up

The market forces haven’t been kind to the uranium industry, which had limped along for decades.

There once were two conversion plants, but one was shuttered and merged into the Metropolis plant, called ConverDyn, more than three decades ago and is run today by partners San Diego-based General Atomics and Charlotte, North Carolina-based Honeywell.

General Atomics is a name Wyomingites know.

The military contractor has its finger in a rare earths demonstration plant in Upton that is viewed as a first step toward putting the United States in a better competitive advantage in the strategic mineral race with dominant player China.

The main process performed by ConverDyn is to take yellowcake from uranium mining operations like Ur-Uranium and convert the granular material into uranium hexafluoride gas, a critical fuel needed by utilities operating nuclear power plants in North America, Europe and Asia.

There are two other conversion plants in the Western world, one in Canada and the other in France.

Russia controls roughly 45% of the conversion market and provides some services to the United States to help fuel the gap, according to proposed federal legislation that would ban Russian imports, but which stalled last December due to political in-fighting in the U.S. Senate.

Since 2022, Ur-Uranium also has benefited from an effort led by the federal government to produce uranium for a $75 million strategic reserve in case it needs to be tapped in an emergency.

Other mining interests within Wyoming plan to kick in uranium to the reserve.

These companies include:

- Texas-based Uranium Energy Corp.; EnCore, a uranium producer.

- Colorado-based Energy Fuels Inc. in Nichols Ranch.

- Australian-based Peninsula Energy Ltd., which said last month that it plans to sell between $88 million and $117 million worth of Wyoming uranium from a mine near Gillette to a European nuclear fuel buyer from Belgium.

Tough Drive

Cash, who is typically based at his company’s Casper headquarters, runs the Lost Creek uranium mine in the Red Desert, a 9,300-square-mile high desert and sagebrush steppe located in southcentral Wyoming.

Ur-Energy’s Lost Creek mine is located in the uranium-rich Great Basin Divide, which covers nearly 4,000 square miles.

Cash said he tries to get out to the mine at least once a week, which is a tough trip.

It’s a 32-mile drive over a bumpy dirt and gravel Wamsutter-Crooks Gap Road from the abandoned uranium boomtown of Jeffrey City off scenic U.S. Highway 287. That road connects the northwestern part of the Cowboy State where the surrounding countryside is rich in the reddish glow of sloping valleys of clay and rock.

The Red Desert provides a breathtaking playground for native wildlife, including coyote, desert elk, pronghorn and wild horses.

The main road through the desert, U.S. 287, navigates the Red Desert over to Lamont, Wyoming, which is another way to travel to Lost Creek, but that’s a tougher 26-mile drive over unmaintained U.S. Bureau of Land Management roads with crater-like potholes and broken chunks of asphalt pavement.

Drivers sometimes navigate around cattle that have wandered onto the road, the longest stretch of which is called Mineral Exploration Road.

“Don’t drive faster than 50 (mph). It’s tempting, but don’t,” Cash constantly exhorts to anyone who’ll listen.

Meanwhile, growing demand for uranium has led Ur-Energy to open a second in-situ mining operation in the Shirley Basin in Carbon County about 130 miles to the east of Lost Creek.

Ur-Energy, the largest producer in the U.S. through its Lost Creek operation in Wyoming, has nailed down a handful of major long-term contracts with electric utility giants over the past year.

Those deals were viewed as the catalyst to boost uranium production, Cash said.

The decision to build out the Shirley Basin satellite project will nearly double Ur-Energy’s annual mine production capacity to 2.2 million pounds.

The mine, which Ur-Energy acquired more than a dozen years ago, has a place in uranium history. The Shirley Basin mine was the birthplace of in-situ mining technology in the early 1960s, though it was suspended in the early 1990s due to low uranium pricing.

In the lobby of Ur-Energy’s production plant, a whiteboard displays the day’s latest spot price for uranium. It’s the reason why the second mine is opening and all the activity at Lost Creek.

Uranium spot prices hit a few decade high of $106 in early February but have since backed off to just under $90 a pound this week, according to Atlanta-based UxC LLC, which tracks uranium spot prices on a nuclear fuel exchange.

“The (Great Divide) basin is just loaded with uranium,” Cash said. “We have contracted half of our licensed capacity, but we are ramping up production.”

Pat Maio can be reached at pat@cowboystatedaily.com.