Police owe a duty of care to suspects they’re investigating, the Wyoming Supreme Court decided Tuesday in a split 3-2 decision.

The decision creates a new avenue by which a criminal suspect can sue a police officer for conducting a negligent investigation if the officer’s case falls apart.

“(The idea) that a governmental entity may have a duty to the public in general but no special duty to individual citizens is no longer viable,” wrote Justice Lynne Boomgaarden in the court’s majority opinion, with Chief Justice Kate Fox and Justice John Fenn in agreement.

Police officers have a duty of care to everybody. Not just to the general public, whom they are supposed to keep safe from crimes, but also to the suspects they’re investigating, the opinion concludes.

Fiery Last Day

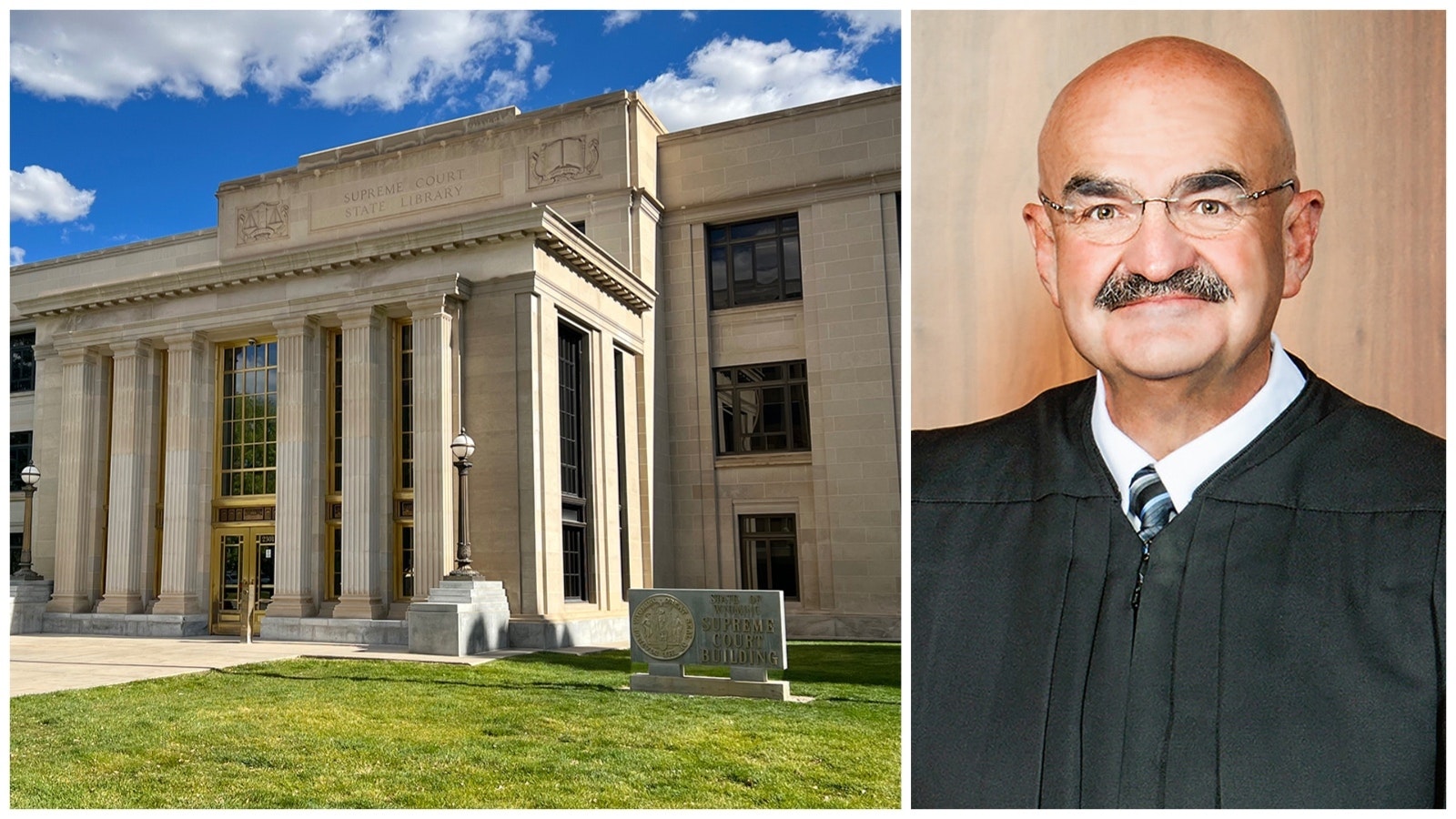

Wyoming Supreme Court Justices don’t often write dissenting opinions, but Justice Keith Kautz penned a blistering dissent in this case — on his last day on the bench.

Kautz retires from the high court Wednesday, his 70th birthday, due to Wyoming’s age cap for justices and district court judges.

Justice Kari Gray joined in his dissent.

“The majority opinion concludes that an investigating officer owes a duty to everyone everywhere, without regard to their relationship to the officer or the claimed injury,” says the dissent.

This creates a new lawsuit mechanism by which criminal defendants can sue investigating officers for simple negligence, because a prosecutor filed charges which were later dismissed, Kautz wrote.

He added that it will “chill” or scare police officers out of making hard decisions and doing their jobs, and will rob elected prosecutors of the discretion they have in making charging decisions.

“The majority opinion puts Wyoming in a unique position — it appears every other state which has considered whether criminal suspects may sue an investigating officer for negligent investigation has included he or she may not,” the dissent says.

But people who fall victim to malicious prosecutions already have a right to sue under the federal malicious prosecution law. That kind of lawsuit is tough to carry: the plaintiff must show she was charged without probable cause and through malice.

It’s easier to carry a negligence lawsuit, and now virtually anyone can try it by claiming a police officer acted “unreasonably,” Kautz argued.

He said that could include people remote to the case, such as suspects’ employers, unpaid creditors and so on.

Prosecutors will be called to court to explain their charging decisions, he wrote, adding that juries (under Wyoming’s apportioned fault law in civil cases) will decide what percentage of fault should go to prosecutors, officers, suspects and others.

It Started With A Weed

This case comes to the Wyoming Supreme Court from a federal court judge, asking for direction on Wyoming law after an Albin, Wyoming, woman sued the Wyoming Division of Criminal Investigation (DCI).

Deborah Palm-Egle lives on a property near Albin, says the Wyoming Supreme Court’s majority opinion.

DCI Officer Jon Briggs received a tip in August 2019 about a suspected marijuana-growing operation on her property.

Briggs and another agent went to the home Nov. 1, 2019, to try to talk to someone but no one was home. They saw a barn and a greenhouse on the property. A barn window was broken and Briggs spotted — and photographed — a green leafy substance hanging inside the barn.

He went to his office and drew up an affidavit to ask for a search warrant.

He also called the Wyoming Department of Agriculture to determine whether it had issued a hemp-growing license in this case, says the opinion. It had not, the department said. In fact, there was a moratorium in effect for hemp cultivation.

The morning of Nov. 4, 2019, officer Briggs and other agents executed a search warrant and seized 327,600 grams of plants from the barn.

Two people were home when the agents arrived. One of them, not named in the opinion, produced a lab-issued certificate of analysis prepared for the High Altitude Hemp Co. and dated Sept. 12, 2019, which showed two plant samples were tested and had a Delta-0 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) level of 0.0%.

The legal limit for THC content in hemp is 0.3% under federal law.

Officers gave the certificates to Officer Briggs and told the Wyoming Crime Lab about them, says the opinion.

Nah, Says Judge

On Nov. 12, 2019, agents sent 10 samples of the plants they’d seized to a lab for testing. Three months later, the lab returned results showing THC content just over the 0.3% legal limit in nine of the 10 samples, says the opinion.

A prosecutor in April 2020 filed a criminal case alleging three felonies and one misdemeanor, accompanied by Briggs’ findings of evidence.

Palm-Egle went to a probable cause hearing Aug. 6, 2020.

The circuit court judge dismissed the case for lack of probable cause. The judge said Palm-Egle had been held out as a hemp expert, was instrumental in passing legislation legalizing hemp in Wyoming, and that the low THC levels reflected an intent to produce hemp, says the opinion.

Then She Sued

Palm-Egle sued Briggs, the DCI and several other parties in April 2022, alleging violations of her constitutional rights and a variety of tort claims.

The case ended up in federal court, where a judge dismissed several claims.

But the federal judge did not want to rule on Palm-Egle’s negligence claims, because this area was not well-defined in Wyoming law and these claims relied on state law. (Federal judges can preside over civil state-law claims when there are also federal laws or federal rights in play.)

The federal judge asked the Wyoming Supreme Court to weigh in on whether Briggs had a duty to investigate Palm-Egle “non-negligently.”

Well, Yes

The high court majority’s answer is yes, he did.

“Accused are presumed innocent until proven guilty,” wrote the majority.

Other jurisdictions have applied a “public duty doctrine” instead, insisting that officers’ chief duty is to the general public whom they’re tasked with protecting. But Wyoming has “never recognized” that, says the opinion, adding that jurisdictions applying that idea have done so “to afford criminal suspects lesser protections” and excuse officers of their duty to behave without negligence.

Though officers have a specific non-negligence duty toward suspects now, Briggs can still argue that he has qualified immunity, the majority wrote.

“Qualified immunity protects good actors,” says the opinion.

It’s a question for the judge to decide early in the case. It protects officers from personal-capacity lawsuits if they were acting within the scope of their duties and in good faith, doing things reasonable under the circumstances, and the acts were discretionary duties, not operational or ministerial.

The majority opinion differentiates this defense from the non-negligent investigation requirement.

The Cases Invoked

The majority cited three cases, mainly, in support of its analysis.

One was the 2022 case Cornella v City of Lander, in which a family had to pay $80,000 for rabies shots because Lander animal control officers lost a bat they’d captured from the family’s home.

The officers owed a duty of non-negligence to that family, the case concluded.

Another was the 1992 case Keehn v. Town of Torrington, in which a police officer stopped a driver for having a burned-out headlight.

The officer smelled alcohol, but the driver didn’t seem drunk.

The driver crossed the road’s center line two hours later and killed three people, the opinion relates from the case.

The high court didn’t sketch the “nature and extent” of the officer’s duty to investigate in that case, but decided the officer did not breach his duty to behave as a reasonable officer of ordinary prudence would.

In the third case, Duncan v. Town of Jackson (1995), an officer was investigating the scene of a truck that drove off the road and down into an embankment. The officer did not look in the vehicle for remaining occupants. The next morning the truck driver was found dead in the driver’s seat.

The high court remanded the case back to a district court judge who had said the off-duty officer was not acting within the scope of his duties.

Where’s The Suspect?

Kautz blasted the majority’s reliance on these three cases, saying not one of them creates an officer’s specific duty of non-negligence toward a suspect.

Rather, they looked at other relationships between the respective officers and the people they were supposed to be protecting, Kautz wrote.

The Keehn case grappled with a duty apart from common law, found in Wyoming’s law against drunk driving.

The Duncan case contemplated a duty toward the victim of the crash, but not toward every individual, Kautz wrote, and he called the majority’s use of these cases “not appropriate.”

Look Into The Future

Lastly, Kautz said the majority should have used an eight-factor law test in looking at any duty Briggs may have owed Palm-Egle.

That test hinges heavily upon whether the officer could have foreseen harm to the other person by his actions.

But in this case, having a prosecutor — not Briggs — be the person ultimately responsible for filing the charges interrupts Briggs’ ability to foresee whether, by investigating a reported crime, he’s going to cause someone harm.

Clair McFarland can be reached at clair@cowboystatedaily.com.