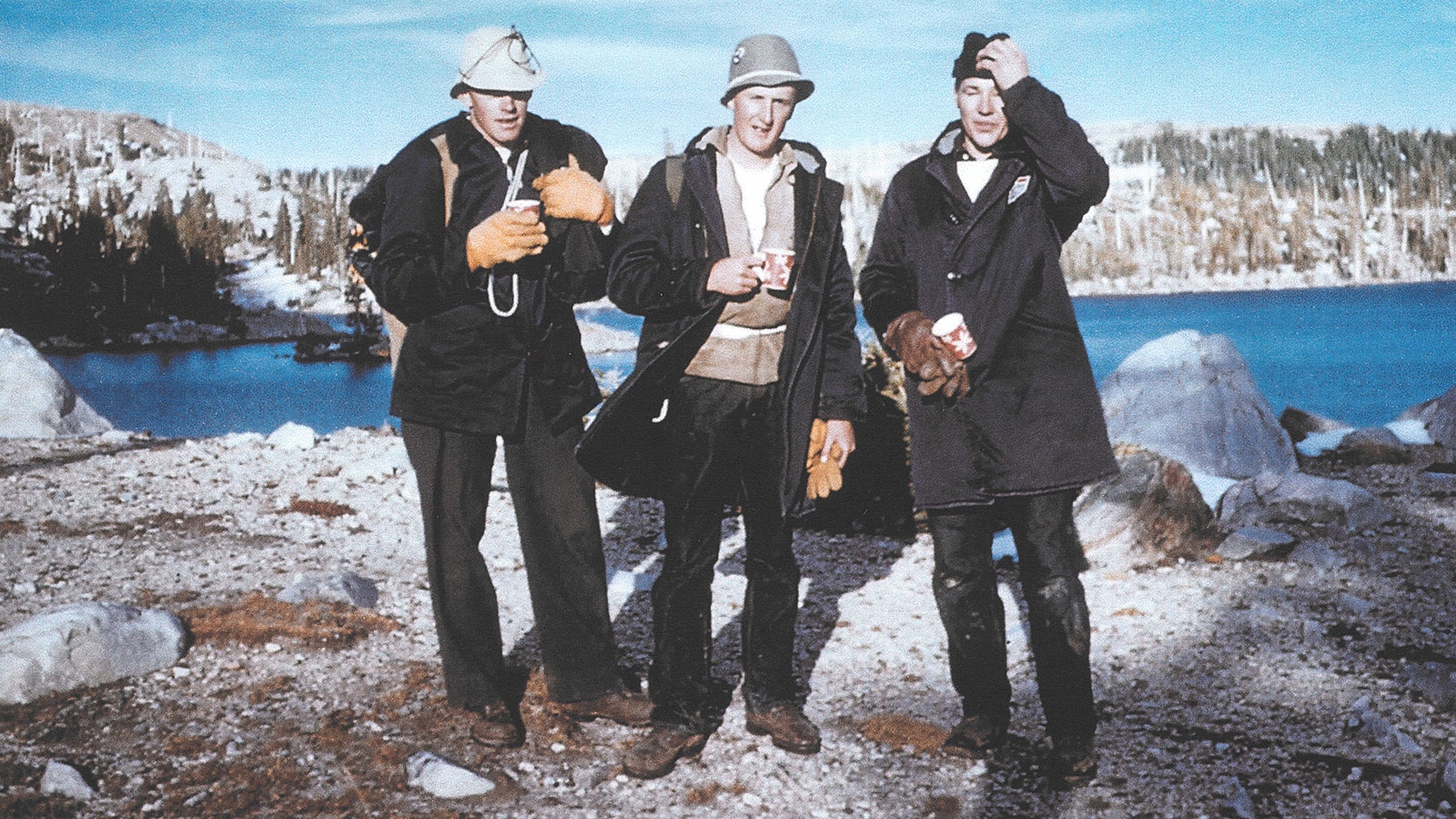

Looking back at his 18-year-old self on the side of the 12,005-foot Medicine Bow Peak west of Laramie, Wyoming, Robert Harrower, 87, is reluctant to talk about what he sees.

That’s understandable.

A University of Wyoming sophomore in 1955, Harrower was part of the college ski team and an informal mountaineering club. For some reason still undefinable to him today, this group of five or so friends skilled with ropes, hammer and pitons became the team tasked with picking fragments of human flesh off the mountainside after United Airlines Flight 409 slammed into it Oct. 6, 1955.

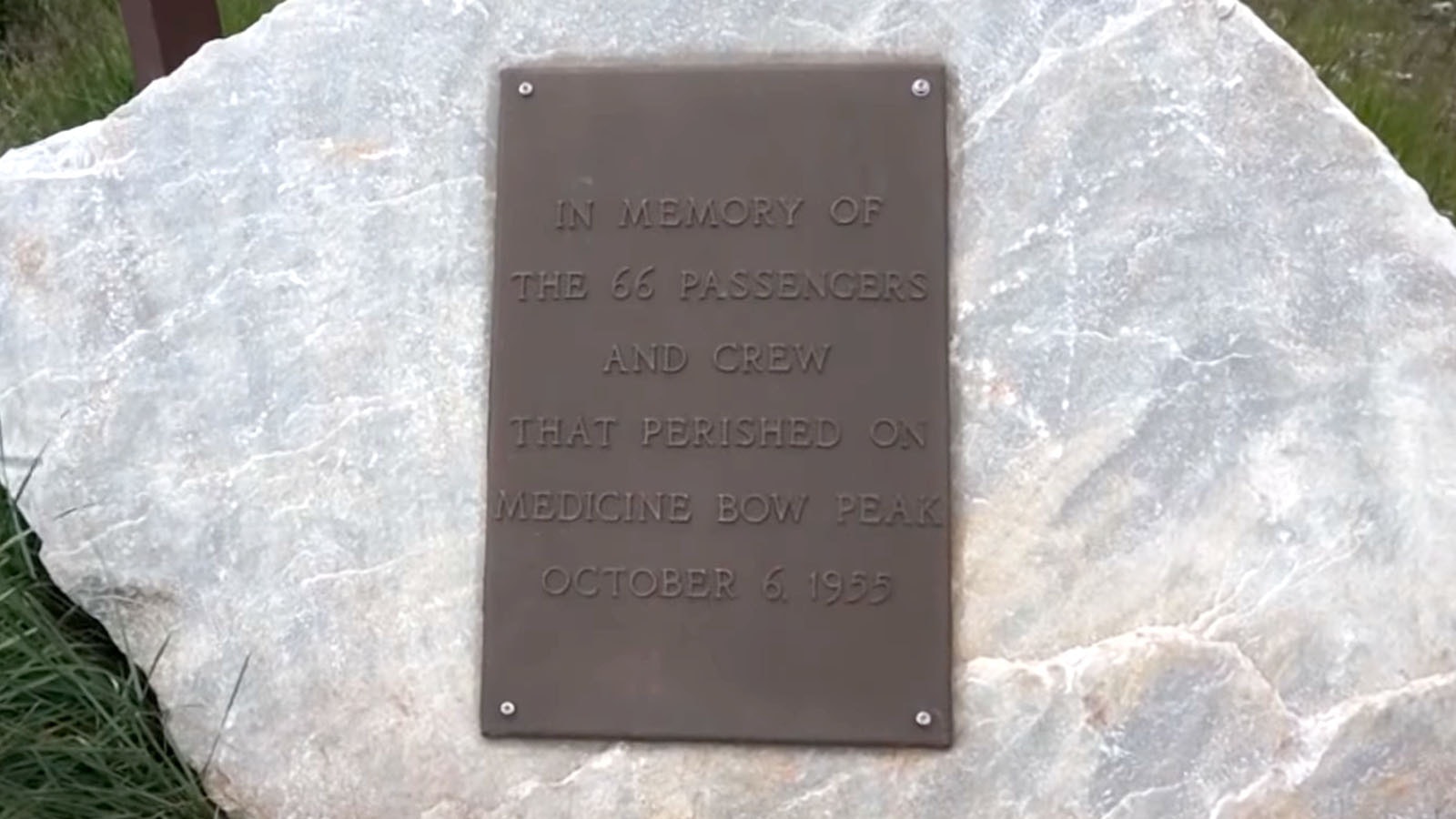

The four-engine plane nearly disintegrated after plowing into the peak at more than 200 mph, killing all 66 on board in what at the time was the worst airline disaster in U.S. history.

While officials organizing the emergency response waited below or at an incident command site a few miles away, Harrower and the others did the unthinkable.

“I suppose some of us had seen a dead body before, but I had never,” Harrower told Cowboy State Daily. “I never handled one or pushed one around or lifted one. Or even parts of bodies, arms, legs, heads.”

Those buddies who joined him in that pre-professional emergency responder era are mostly gone now, except for Harrower and possibly another college colleague he has lost touch with. Another friend who lived in Laramie and was on the mountain with him nearly 70 years ago died last year.

“I wrote his wife and told her of my memory of him digging in that pile of wreckage on the ledge and coming up with the body of that baby, and of course his face is blackened from the soot and the smoke and dirt and the tear stains down his cheeks,” he said. “And I still cry when I think of that. He had that baby in his arms, and he turned to us and said, ‘I think I will carry this one down,’ and he did. He wrapped it and put it in body bags.”

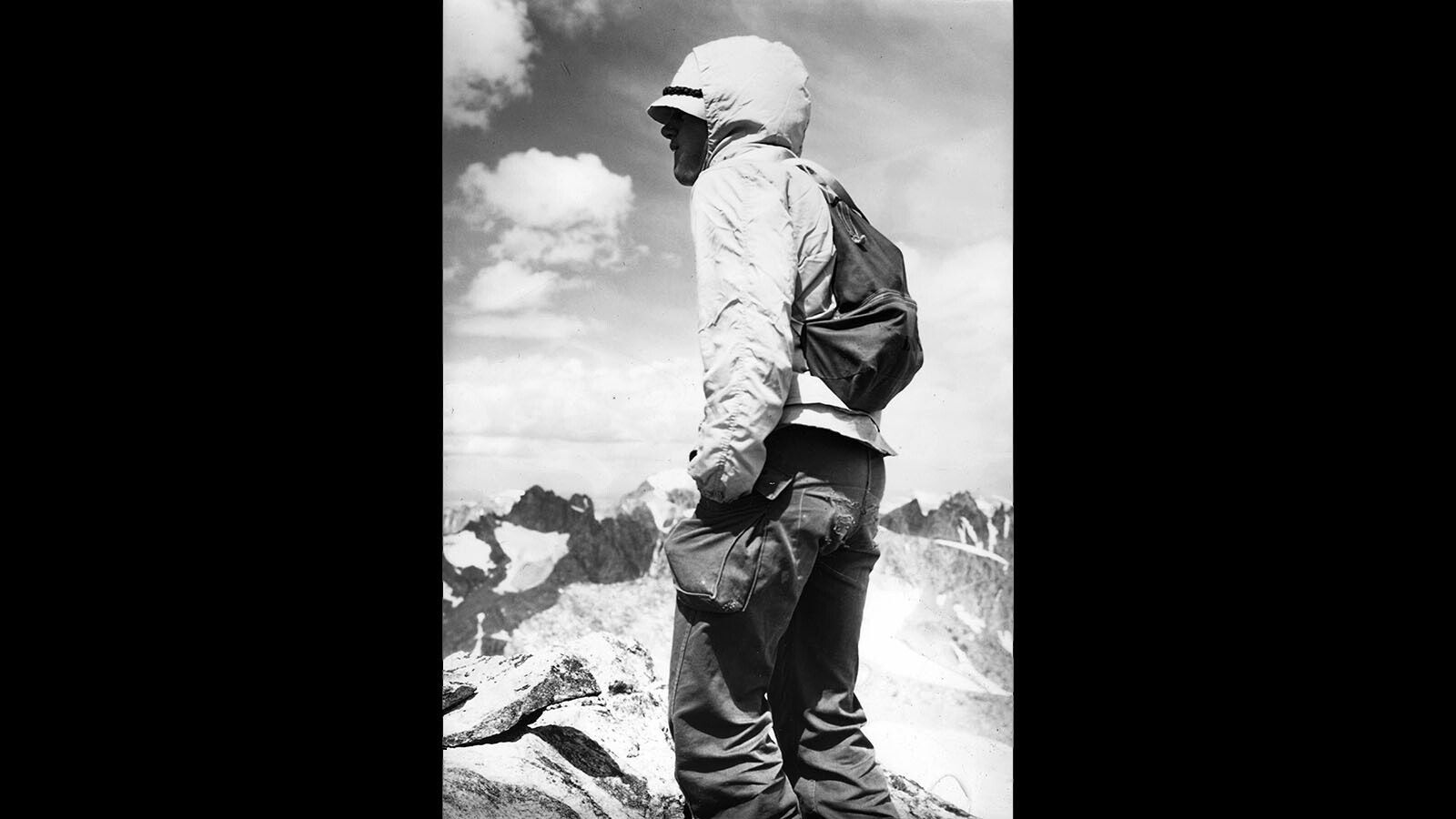

Harrower, who lives in Pinedale, Wyoming, has had a full life as a structural engineer who worked on nuclear projects and traveled the world. He also continued climbing mountains — but never again Medicine Bow Peak.

“I think we were probably stunned, just overwhelmed with the stench, smoke, dust, blowing stuff,” he said of the shock responding to the scene. “It was probably something that hell looks like, I don’t know, but I am going to guess at that.”

The Mountain Scene

Harrower’s journey to the mountain began when two of his buddies, both former roommates at the University of Wyoming, heard there was crash on the peak. They drove out to the scene, where officials asked them to carry an emergency body basket up the mountain. They declined and drove back to the college.

The next morning, Harrower joined his buddies to drive back out to the mountain with their climbing gear in the trunk. They found thousands of people and gawkers at the site. There was a Wyoming state trooper and friend who sometimes joined the climbing club for their mountain adventures at the scene directing traffic.

Harrower said the trooper helped them get through the crowd, and it could have been a word from the trooper to someone that put them on the mountain.

He said after starting their journey up the mountain through a gulley, they found their first body. It was intact, one of only two or three they would encounter as full bodies.

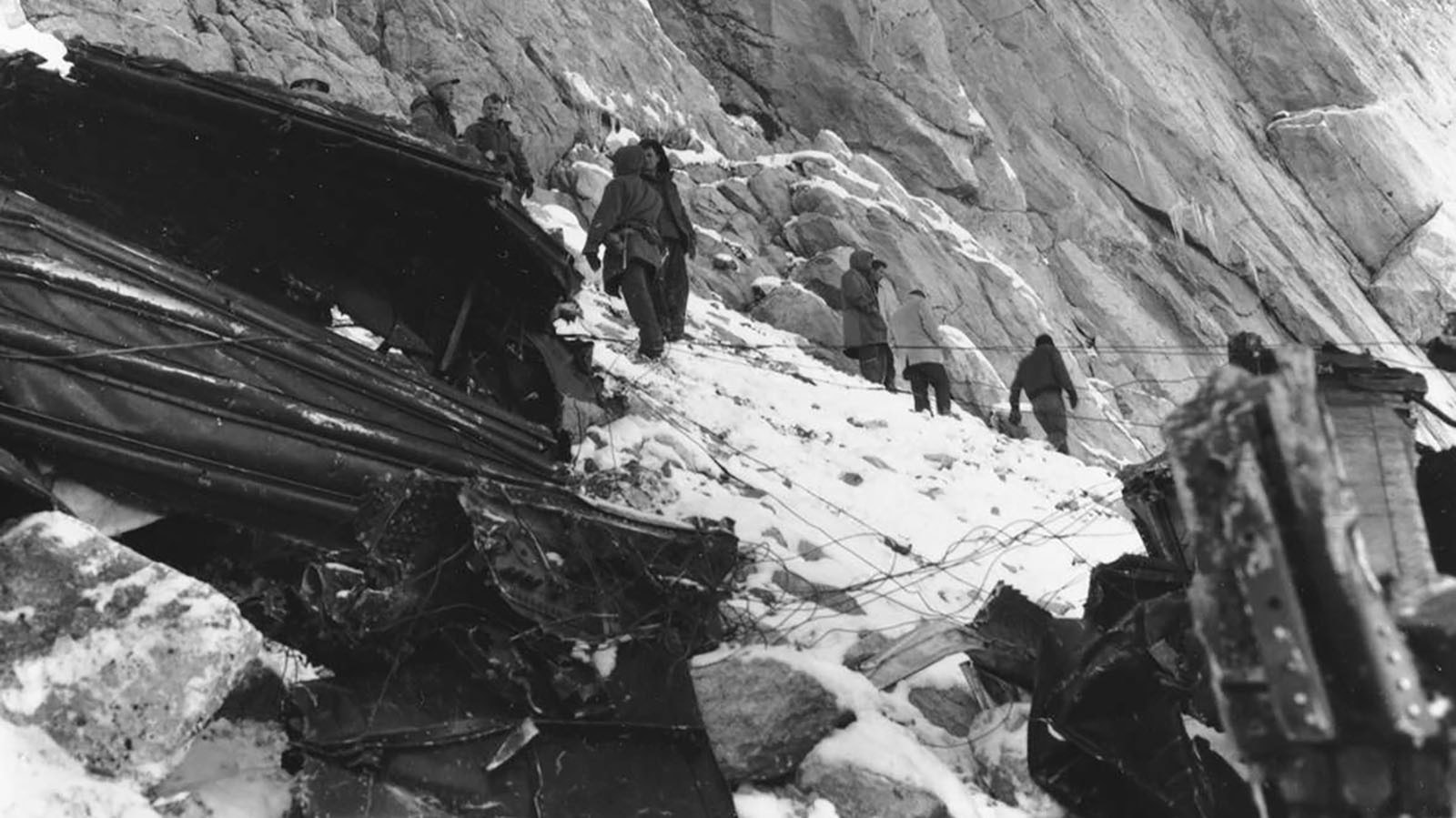

Once up near the top they were confronted with a tail section hanging precariously near the peak. Body parts, metal, smoking debris, hundreds of pieces of mail were scattered around, and the distinct and putrid smell of burnt human flesh.

One vivid memory is when Harrower saw the remains of a stewardess against a rock where she was thrown.

Harrower said a Colorado search and rescue team that responded to the scene wasn’t not up to the task. They weren’t trained for the mountain climbing and soon were reassigned someplace else.

So, his team of college students started to fill the body bags they had been given and quickly realized the process was not going to work, he told Cowboy State Daily. On the side of the mountain, roped in, they would place body parts in the bag and then try to move the bag, which would hit jagged rock and tear open.

So, his group and the authorities below the crash site devised a system using a cable attached to a trolley like bucket device with rubber wheels on the cable connected to ropes to get the body parts in bags down. They also picked mail and pieces of the plane off the mountain.

‘No Direction’

Harrower said the officials “in charge” were based at a former University of Wyoming science camp a few miles from the crash site and his team would return there after a day of working on the mountain.

“The thing that I remember was that we had no direction from anybody — from United, from the sheriff, from the FAA,” he said. “No direction, except, ‘Look for this item.’”

Representatives from the FAA, U.S. Postal Service, local sheriff’s department, FBI and other interested parties would ask the team to look for or retrieve certain parts of the plane, such as instruments from the cockpit, or pieces of U.S. mail that was on the plane. The FBI wanted two specific packages that they never found.

“Finally, it dawned on us that nobody (else) was going higher than ‘X’ feet on the mountain and we were the only ones on the mountain,” Harrower said. “It was good for safety reasons and good … climbing wise.

“I really think nobody wanted the legal liabilities of having been up on the mountain to see what it looked like.”

He said at one point, the airline offered the team “a lot of money” if they could bring the horizontal stabilizers down off the mountain. But it required them climbing into the unstable tail section of the airplane. And though several tried, it proved too dangerous.

“The tail section was kind of wobbly anyway, even though it was anchored with cable,” Harrower said. “So, nobody was brave enough to do that.”

The tail would eventually be shot off the mountain using large-caliber Wyoming National Guard artillery.

‘Like The Inquisition’

Harrower said after the second day they were numb to the task of picking up human heads or other body parts and putting it all in the body bags.

“It was like the Inquisition or something. It was just bad,” he said. “We should have just stopped and said, ‘I’m not going to do this anymore,’ that’s the way I’m thinking now.”

During his days on the mountain, he found a Kodak Retina II 35-mm camera with a cracked lens at the crash scene. He obtained some film, took the old film out and started taking photos of the crash debris. He would turn his photos over to the University of Wyoming, and today they are at its America Heritage Center.

Harrower took what’s become the most recognizable photo of the crash — the plane’s tail section hard against the mountain with cables running over it.

After eight or nine days of work on mountain, the mission was called complete. Harrower said that for their services, United Airlines wrote each member of the team a check.

“I don’t know if it was everybody on the mountain,” he said. “But the people I know got a check for $350 from United Airlines, which at that time was pretty good money for 1955 college kids.”

Some Regrets

Harrower said he took some of the money and bought a Kodak Retina III C camera that he took with him to Antarctica, Russia and other places around the world.

Harrower graduated from the University of Wyoming with two engineering degrees and worked for a Philadelphia company building nuclear power plants.

Years later, after dealing with the harsh memories of his friend carrying the lifeless baby down the mountain and the stewardess against the rock, Harrower said he looks back at his young self and wonders why things happened the way they did and why there wasn’t another method or means to deal with the crash site and keep it more sacred.

“It was sacrilege, terrible,” he said about how the scene was processed. “I think they should have bordered the thing off and had armed guards kept there for as many years as it would take to heal up and let it go at that.

“I don’t think I felt that way when I was there. I don’t know when that came over me that I just said, ‘Stop, let’s not do this, it’s terrible.’”

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.