Students and professors have rolled their eyes for decades about an urban myth that a nuclear-powered reactor was set up in the basement of the University of Wyoming’s aging engineering building.

The reactor can no longer be the butt of jokes and the urban myth has been busted. It was a real thing.

The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Agency has reached deep into its archives to confirm to Cowboy State Daily the existence of the reactor once at UW, and has since been crated up and shipped to Florida. The 1950s vintage reactor is in someone else’s heap today.

The UW part in the history of this tiny nuclear reactor began in the 1960s, a time of great angst and political unrest in America.

Dr. Ryan Brought It With Him

Dr. Victor Albert Ryan, a nuclear chemist who began teaching with the University of Wyoming during those turbulent years, didn’t rub shoulders much with his university colleagues.

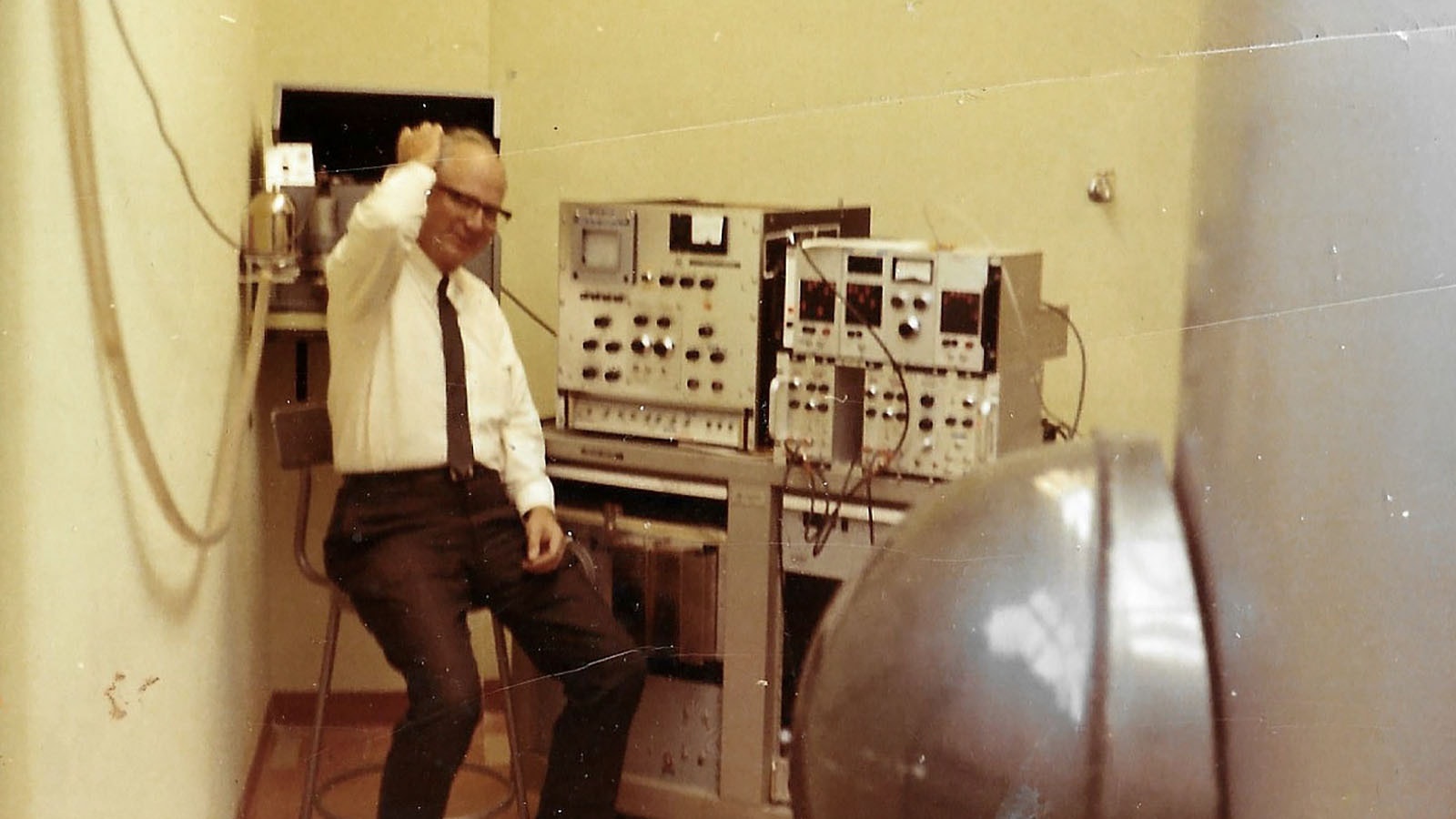

Instead, he dove into teaching his nuclear chemistry courses and encouraged his students to be curious about their research – especially those who worked closely with him on the tiny research nuclear reactor that he brought with him to UW. Students loved his Socratic method of teaching.

He wasn’t popular with his professorial colleagues. Maybe it was because of the anti-nuclear sentiment of the Vietnam War era, or maybe it was because his colleagues were jealous of him snapping up a highly vaunted National Science Foundation (NSF) grant valued at $1.2 million to land the tiny nuclear reactor on UW’s campus.

No one close to Dr. Ryan who was interviewed by Cowboy State Daily really knows for sure why he wasn’t popular on campus with higher-ups in the administration, or why he preferred toiling quietly on a tiny research nuclear reactor in the subterranean basement of UW’s main engineering building over above-ground activities at the white-clothed tables of the university club and social engagements.

In all the excitement about what role Wyoming can play in the country’s and world’s future with power generation through new micro-nuclear reactors such as what the Bill Gates-backed TerraPower is putting in near Kemmerer, many seem to have forgotten that the Cowboy State has a long and rich nuclear past.

‘Missing Link’ No Longer Missing

The obscure UW professor is perhaps a forgotten titan, or “missing link,” in this history. But thanks to an 81-year-old former student, the professor’s son and others the professor’s and University of Wyoming’s part in a nuclear past is starting to be remembered and explored.

Gerry Meyer, the 104-year-old former vice president of research with the University of Wyoming, told Cowboy State Daily that Dr. Ryan’s prominent role in running the reactor was because of his “interest in the subject.”

The university dismantled the reactor in the early 1970s because the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), which at the time was the regulator of all-things nuclear, had paid a surprise visit to the campus and didn’t find anyone at the controls.

“We really caught hell,” Meyer recalled. “I said, ‘That’s enough,’ and that’s why we deactivated the system and passed it along to someone else.”

Greg Ryan, Dr. Victor Albert Ryan’s son, said some of the unfavorable disposition toward his father may have been fueled by jealousy from colleagues over the $1.2 million NSF grant that they thought should go elsewhere. People in academia often get up in arms over such things, he said.

With inflation factored in, the NSF grant would have been worth $10.7 million today.

And Then It Was Gone

Dr. Ryan went to his death bed not knowing if anyone really cared about his pioneering work with the research reactor on UW’s main Laramie campus, according to his son.

His work on the nuclear reactor was related to research and training, materials testing, and the production of radioisotopes for medicine and industry. One doctoral candidate student used to the reactor to test mercury in fish.

These reactors are much smaller than power reactors, like the kind that light up the electrical grid or propel aircraft carriers or submarines. Still, they must be handled with the same kind of gingerly touch as the big reactors. They’re all nuclear and can contaminate everything around them with radiation if not handled properly.

Dr. Ryan never got the traction to continue his work to make monumental findings with the reactor because it was eventually taken away.

For sure, a handful of graduate students who trained under Dr. Ryan eventually went on to conduct nuclear work at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee where they worked on experiments related to enrichment of nuclear fuel for nuclear weapons, as well as at its related sister-organization, Los Alamos National Laboratory, in New Mexico.

After Dr. Ryan made his mark at the university with limited research involving the reactor over a stretch of roughly half-a-dozen years, he left in the mid-1970s to become UW’s head of public safety, perhaps because of the AEC’s surprise visit.

Meyer, who was dean of the university’s College of Arts and Sciences nearly 60 years ago when the nuclear work was going on at the university, said his friend was moved into the safety job to oversee “all of the radioactive substances” handled on the campus – including tritium, which was used in agricultural research.

UW’s budding nuclear program came and went without fanfare when Dr. Ryan departed from his position of overseeing the reactor.

The reactor was packaged up and shipped off to Central Florida Community College in Ocala in 1974 for a much-needed reactor training technology program, according to archived records provided by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Agency and historical records kept by Central Florida.

The NRC said that the reactor’s fuel was transported 500 miles to the northwest to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Idaho National Laboratories in Idaho for storage.

The 83-year-old Dr. Ryan died in 2003 without notice from his UW employer or recognition for his nuclear work in Wyoming.

Upset Students

But then came delivery of a digital edition of UW’s Foresight magazine published this fall and winter by the UW College of Engineering and Physical Sciences. There was an article about the establishment of what it reported as the “first ever” nuclear chemistry facility a couple of years ago.

A former UW student, 81-year-old Robert Galyan, who was a graduate student who worked with “coach” (as Dr. Ryan and a few other students affectionately called him) couldn’t believe there wasn’t any mention of their professor’s nuclear work.

“This was not a ‘first ever’ program,” he wrote in a Feb. 13 email to the chemistry department. He said he never received a reply.

Galyan, who is surviving with three lung diseases and lives on oxygen tanks in Thermopolis, said UW has forgotten Dr. Ryan.

“Nobody remembers him,” he told Cowboy State Daily of his former teacher’s contributions to nuclear research in Wyoming.

Galyan visited the old engineering lab last year by himself, roaming the halls of the sandstone-façade building where the reactor once hummed to life.

The basement where the reactor was situated has been renovated. Gone is the “heavy steel door” located on the right side of the old ramp — which is still there — that led into the reactor room, he said. There’s classroom space there now.

Also gone is a lighted international radiation symbol — a trefoil around a small central circle representing radiation from an atom — located on the rear of the building that would turn a brilliant red when the reactor was activated.

“I’ll always remember it,” said Galyan, who wrote a thesis involving the reactor related to mercury and fish.

Steven Aumeier, senior adviser to strategic programs with the Idaho National Laboratory in Idaho Falls, said Dr. Ryan’s reactor work is akin to a “missing link” in Wyoming’s nuclear history.

“I was surprised, as I had never heard that the University of Wyoming had a research reactor,” said Aumeier. He is an adviser to UW’s now 2-year-old Nuclear Energy Research Center.

Lost To Time

The story has been told often that Wyoming was home to the first portable land-based nuclear reactor in the United States from 1962 to 1968. It was built near Sundance and generated a little over 1 megawatt of power for three large radar domes at the defunct Sundance Air Force Station.

But the existence of the nuclear program at UW from a half centry ago was obscured by the passage of time. Not even university officials today are aware of Dr. Ryan’s work.

The nuclear buzz these days is overshadowed by what TerraPower is doing to build a nuclear demonstration plant in Kemmerer.

In 1968, when Gates was dropping out of college to start Microsoft with childhood friend Paul Allen, Dr. Ryan was applying for the big NSF grant to bring a tiny nuclear reactor to UW’s campus, which he did.

By all accounts pieced together from archived records provided by the NRC, the Atomics International-built reactor that Dr. Ryan got with the NSF grant was packaged up at the New Jersey campus of Rutgers University and shipped across the country to UW, where it was given a home in what is still the engineering building.

The reactor’s arrival at UW is a mystery.

Meyer thinks it may have come in the mid-1960s, while Dr. Ryan’s son and Galyan think it may have arrived in the midst of the Vietnam war in 1968 and a time of growing anti-nuclear sentiment in the U.S.

Some people who knew Dr. Ryan believe his work on a nuclear reactor, plus the jealousy factor with the NSF grant and getting his reactor placed in the engineering building — not the chemistry building where Ryan taught — may have combined to make Ryan a not-so-popular educator.

“Jealousy was very tough on my dad. It stressed him out a lot,” said Greg Ryan, who pointed to some bullying tactics, like his father’s valuable telescope once being stolen from the reactor lab where it was stored.

No one knows for sure why Dr. Ryan and his work are not more prominently remembered today.

Nuclear Pioneer

“He was a pioneer in nuclear work in Wyoming,” said the younger Ryan, who on occasion would visit his father at work.

Stories abound about the reactor at UW, like getting spare parts from Los Alamos National Laboratories in New Mexico or from the former Rocky Flats nuclear weapons complex in Colorado.

They sometimes were forced to jerry-rig things as they went along.

Galyan told one story about connecting communication wires from the reactor’s control room to a computer mainframe located across campus by stringing them under UW’s Prexy’s Pasture through an old steam heating system.

“I’d venture to say it was the first remote terminal ever in Wyoming,” he said.

When he was a young teenager in the late 1960s, Greg Ryan recalled visiting his father at work.

His father admonished him to not climb a wooden staircase that led to the top of the mini-reactor. Use of that was only permissible for the lab’s graduate students who were allowed on top of the stairs, where they could push or pull fuel rods into the reactor’s core to control the ebb and flow of power.

This was not a huge reactor with a 500-megawatt containment vessel several stories high. Rather, the UW reactor was 10-15 feet high with a pool of water built into the floor nearby where the rods could be tossed in to cool them off quickly in the event of an emergency, Galyan explained.

The UW reactor was so tiny that it produced roughly 12 watts of power — all for teaching and research purposes.

“It definitely was a nuclear reactor,” said Galyan who was the last person to get a nuclear operator’s license to run the reactor.

Isaac Asimov Connection

After Greg Ryan’s mother passed away a year ago, he rummaged through the papers left behind by his father at the family’s homestead ranch in Saratoga — a property that has been in their hands since the Civil War — and gave them to the Wyoming State Archives in Cheyenne to catalogue and do whatever they do with such things.

Ryan also combed through books left behind by his father, who was a voracious reader. He discovered correspondence with science fiction writer and biochemist Isaac Asimov about topics written on indecipherable notes tucked inside the yellow and tattered pages of Asimov’s literature.

Meanwhile, the memories that Dr. Ryan kept with him of stories told him by his mentor from the University of Minnesota about Marie Curie, the Nobel prize winner who did groundbreaking research on radiation, have gone to his grave, according to Greg Ryan.

“Dad was a smart guy,” he said. “He was a pioneer who got a reactor to Wyoming when nobody had one. He hasn’t gotten his due.”

Contact Pat Maio at pat@cowboystatedaily.com

Pat Maio can be reached at pat@cowboystatedaily.com.