The woman who became known as Wyoming’s “Sheep Queen” understood the perils of the frontier.

She faced mountain lions, dealt with threats from cutthroat cattle ranchers, and went on to become one of the most successful ranchers in her day.

Lucy Morrison Moore knew how to live in a “man’s world,” taming a hardscrabble Wild West frontier while famously never putting up with any profanity.

“She was a force to be reckoned with. In a time when women weren’t really forward, she was living in a man’s world,” said Terri Geissinger, a descendant and researcher who is writing a book about Morrison and her family. “When we think about what she was faced with, with men fighting with their guns and reputations, they came up with the name ‘Sheep Queen.’”

It wasn’t meant to be a compliment, and while Morrison would’ve never chosen the nickname for herself, she owned it.

“She said at first it was probably kind of sarcastic, but she ended up wearing that crown,” Geissinger said.

California Start

The future Sheep Queen was born in 1857 in Placer County, California. At age 5, she would ride a pack mule with her family from California to Illinois, and then to the Bannock and Virginia City area in Montana as gold was making a lucky few rich and a lot of dreamers miserable.

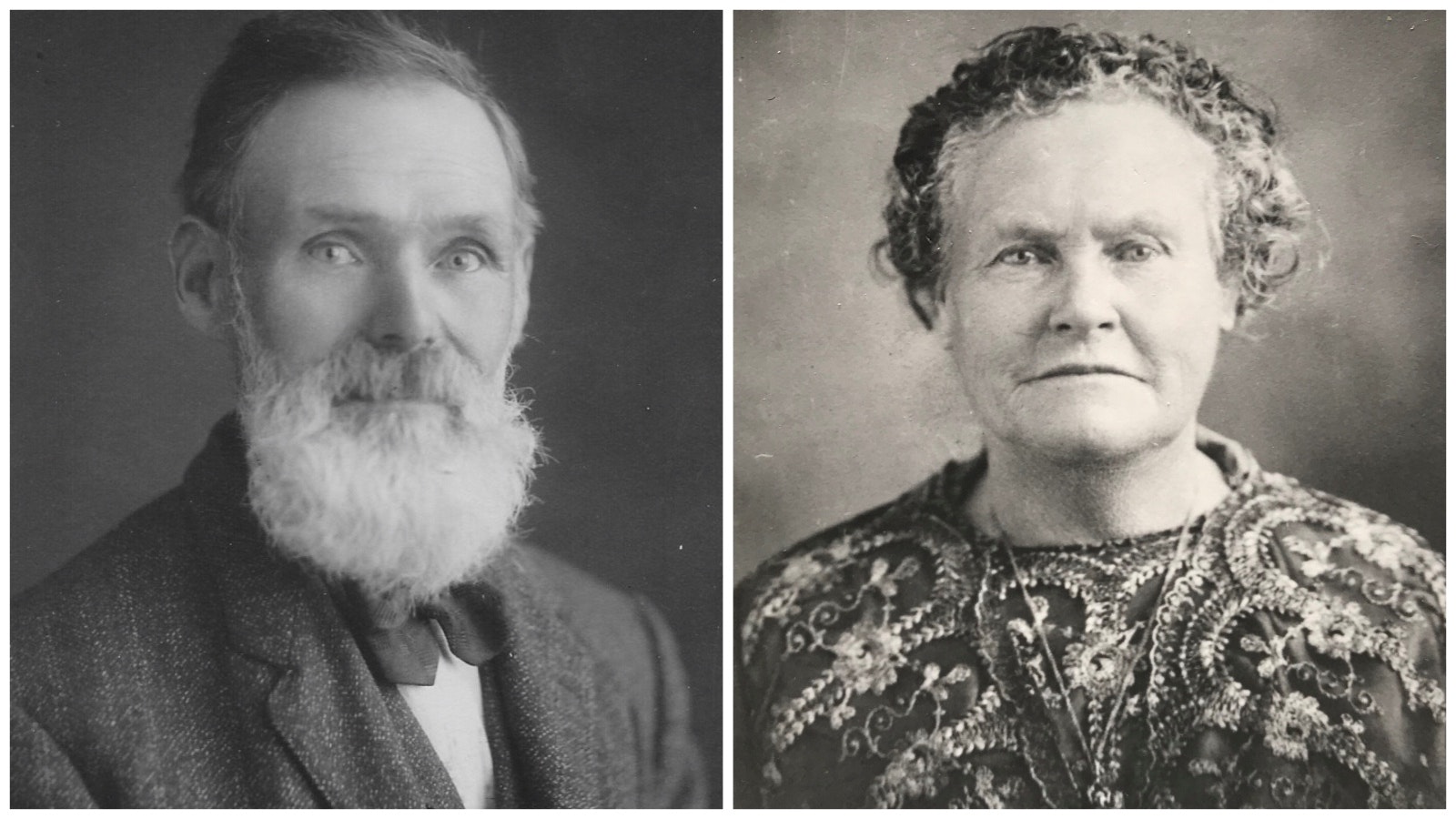

Her family moved to the Soda Springs area of what is now Idaho, where her father had a freighting business serving the gold fields. At 16, Lucy married Luther Morrison, who was 44 at the time. Morrison had traveled the Oregon Trail at 20, was well educated, had been a legislator for Idaho Territory and had a successful sheep operation.

“They were great friends. Luther had known her all of her life,” Geissinger said. “It worked, and they built a huge business and were very successful.”

The Morrison’s moved to Wyoming Territory in 1881 into South Pass City. They brought 2,000 sheep and were convinced to stay there for the winter because they had an infant daughter and two other small girls. By the end of the winter, they had survived, but had only 200 sheep left.

When spring came, they chose to move forward and spent the next few years grazing their sheep through the interior of what is now Wyoming. Their range included the south the Casper area and Thermopolis to the north, and eventually Luther built a cabin at the base of Copper Mountain about 1884.

Morrison was an expert with a broad axe, and the cabin survives. It’s now in Cody as part of Old Trail Town.

Alone On The Frontier

During the early years on the range with their sheep, Luther would go to Rawlins twice a year for supplies. Lucy would be left alone with her children, three girls and a boy.

Geissinger said that during these times, Lucy afraid of encounters with tribal members, and when she saw them coming, she would dot their faces with flour and have them lie down in the tent. When the natives arrived at the camp, she would tell them, “small pox.”

But there’s only so many times a family can have small pox in the 1880s and survive.

“She did it one time too many and the kids are back up playing and doing their thing and the Indians came back around and said to her in English, ‘Smart woman,’” Geissinger said. “And then they never bothered her again. That was one of her stories.”

On another occasion with Luther gone, she was faced with a mountain lion “who nearly got her” and killed many of her sheep one night, Geissinger said. The weapon available was too heavy for her to shoot, so she ground up glass and put the shards in the sheep carcasses.

Her tactic was successful.

“That mountain lion was dead within a few days,” Geissinger said.

As the Morrisons built up their herds, mainly for wool, prosperity followed.

Luther had built a stone ranch that featured the first reservoir in Wyoming outside of Casper. That feat is mentioned on his gravestone. He also became a commissioner for Natrona County and the couple would build one of the first homes in the city.

Opposition

Prosperity also brought opposition from Wyoming’s cattlemen.

Lucy preferred to live out with the sheep on the sheep wagon built for her by Luther. During the range war years, they were not immune to threats.

On one occasion, she returned from a trip to Thermopolis and discovered that all of her horses had been shot. The Natrona County Tribune on Sept. 23, 1897, stated she was offering a reward.

“She had quite a few entanglements and she was afraid for her life,” Geissinger said. “I have a letter from her thinking that she is going to end up like another sheep owner who was killed. They served beef in their camp because they did not want any kinds of accusations that they were stealing cows. They were pretty straightforward.”

Faith For The Family

Even though sheepherding kept the family out on the range for much of the year, Geissinger said Lucy paid attention to education and to her faith. The children were taught to read and write, and when older were sent to private schools in Nebraska.

Biblical standards and Lucy’s Methodist ways were enforced inside the camp and business. No swearing, no drinking, and no abiding those who do.

Success meant the couple would also ship lambs back East, as well as shear their flocks. Geissinger said her research shows shortly before his death in 1898, Luther was involved in creating and leading a state wool growers association.

After his death Lucy, then 42, married a sheepherder, Curtis Moore, 39, in 1902. He had been in her employment. Before they married, she gave him a band of sheep, 1,000 head.

“The reason she said she married him was that he didn’t drink, he didn’t cuss, he was clean cut, and he had a family back where he came from,” Geissinger said. “She gave him the band of sheep because then she could say that she married a ‘stockman’ not a sheepherder.”

Moore kept the books for the business and would be beside her until she died.

A Lot Of Groceries

In 1902, an ad dug out by Geissinger from a Natrona County newspaper shows Lucy ordered 16,000 pounds of groceries for her herders and company supplies from the general store in Casper.

In 1904, the Sheep Queen faced down more intimidation from cattlemen. In May that year, her 21-year-old son Lincoln was standing on a sheep wagon tongue near Kirby Creek and was shot in the stomach area.

She kept pouring the only antiseptic she had, vinegar, on his wound. He would heal.

“She ended up hiring Joe LeFors, a famous detective, to find the shooter,” Geissinger said. “They did apprehend that man, but it was 10 years later. He was found in Montana.”

As the new century moved on, Lucy Morrison Moore would continue to assert herself. The home she and Luther built in Casper would need to be moved for a post office. She negotiated the terms.

There were trips to Europe with her children, but she would always return to her sheep.

Geissinger said when automobiles started arriving in the region, Lucy was an early buyer.

“She got a brand-new car, probably from Casper. The first thing she did was there were a couple of lambs that needed help, and she put them in the back seat,” Geissinger said. “And her son gave her a hard time about it … and she turned to him and said, ‘The sheep paid for this car, they can dang well ride in it.’”

‘Fighting Shepherdess’

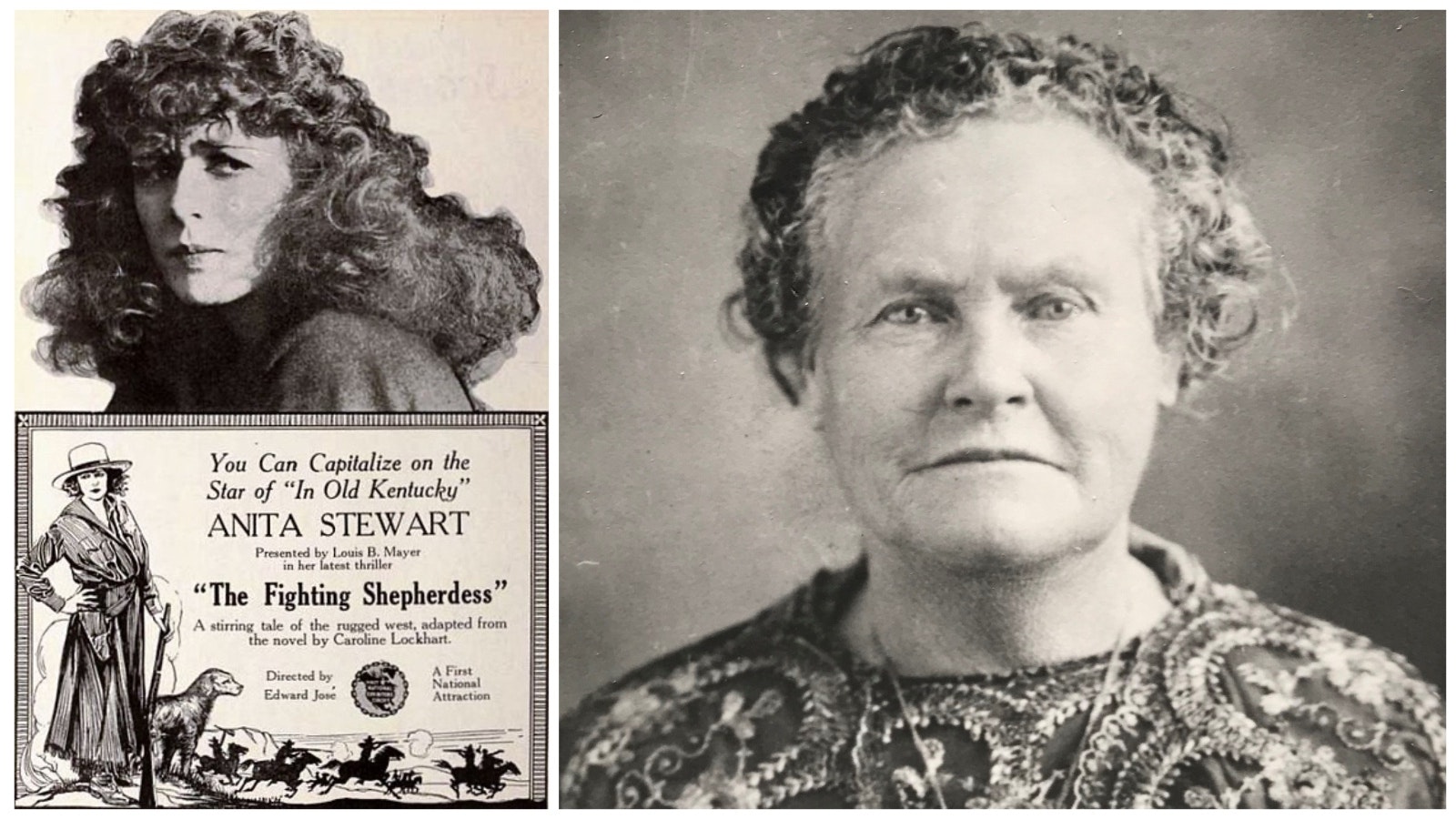

Famous author and later Cody newspaper publisher Caroline Lockhart spent a summer in the sheep camp with Lucy and her family in 1919. That experience stirred her imagination to write a fiction book that became a best-seller titled “The Fighting Shepherdess.”

“When Lucy read the book, she hated it because it’s just was kind of about a grumpy woman on a sheep ranch defending herself against the cattlemen,” Geissinger said. “So, it is kind of based on her, but it is not her. It kind of shot her reputation up.”

In 1920, MGM Studios made a movie based on the book, but it didn’t do well, Geissinger said.

Lucy and her husband would buy property in the Los Angeles area to spend the winters, and she owned other property across the state. But one bad winter, Geissinger said the Moores returned to take care of the sheep.

At her death Sept. 24, 1932, at her daughter Elma Butler’s home in Casper, the “Sheep Queen” was remembered as a Wyoming pioneer.

“Mrs. Lucy L. Moore, Pioneer Wyoming Resident, Succombs,” reads the Casper Tribune Herald headline on Sept. 25, 1932. A few days before her death, the same paper reported, “Mrs. Lucy L. Moore, known as Wyoming’s sheep queen, is in critical condition at the home of her daughter …”

Geissinger said her great-great-great-grandmother’s legacy includes her faith, love of family and love for her sheep.

“What stands out is her dedication to taking care of her animals and to them taking care of her,” she said. “She was very God-fearing, and she loved the open land.”

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at: Dale@CowboyStateDaily.com