If a picture is worth a thousand words, how much for this one? How many words are conveyed in a thousand of these? Ten thousand? A million or more?

Because this iconic photograph featuring the weathered T.A. Moulton barn with the Wyoming Tetons soaring majestically in the background is one of America's most emblematic images. This one shot captures the pluck of the pioneer spirit against the wild and untamed Western landscape.

Strain your ear. You can almost hear Ray Charles singing, “For purple mountain majesties …”

The barn is without doubt the most photographed outbuilding in the world. And there is good reason so many countless Cowboy State tourists have turned their camera lenses westward for the snapshot.

A tourist from China was asked years ago what he knew about the barn, if anything, as he busily snapped away on a picture-perfect July morning. What was it that spoke to him? How many words would be captured in his photograph of it?

An interpreter relayed the question. The man’s finger froze over his shutter button. He lowered the camera from his eye and smiled as wide as a Wyoming sky.

“Ah, cowboy,” he said with excitement, and went back to clicking.

Shoot your shot today in black-and-white and anyone would swear the moment is from the 1800s. Shoot it tomorrow and the panorama looks the same as it ever has.

The barn, sturdy and weatherworn.

The mountains looming ever-present.

Both viewfinder foci play out their dutiful roles in a portrait of the American West.

When professionals capture the scene, it looks fake, Photoshopped.

There is power in this place a Polaroid only begins to touch.

Did that frazzle-haired boy in his boots and pajamas even look up at the Tetons as he shuffled his way to Gertie in the half-dark with an empty pail? Did he know he was living the cover of the Saturday Evening Post?

Snapshots today of the Moulton barn are reminders of yesteryear, a time we remember as easier. It wasn’t. Our recollections don't carry the blood and blisters and bankruptcies it took to make a way in the wilderness.

Ready For A History Quiz?

Think you know everything about the famous barn and its setting? Don't be too sure.

For one, there are two — two barns that is. Both are often photographed, but one is the more popular of the two.

Also, do you know why this neat lane of properties, comprising Sections 28 and 29, was known locally — and somewhat derogatorily — as “Mormon Row” even when its post office clearly read Grovont?

Who were the people who settled here and why? What happened that caused its collapse into the ghost town it is today?

Barn trivia: Who were the first two occupants of the TA Moulton barn? Bonus points for their names.

And what business does Hollywood legend Henry Fonda have milking a cow in that barn?

All shall be revealed as we run it back on the row.

How Did We Get Here?

The Antelope Flats/Mormon Row area is located about 14 miles north of Jackson, just outside of Kelly in the southern end of the valley known as a “hole” to mountain men of yore. Settlers picked the spot for its rich alluvial soil, which was marginally better than the rock-filled dirt covering most of the valley.

Blacktail Butte, to the immediate southwest, provided shelter from the incessant winds threatening to blow away topsoil.

Beginning at the turn of last century, leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints sent parties from the Salt Lake Valley to establish new communities outside of Utah, Idaho and Arizona.

The directive was well-timed with the Homestead Act of 1862, and subsequent incentives to settle the West like the Timber Culture Act, added in 1873, and the Desert Act of 1877.

Wyoming was slow to grow its population before statehood in 1890. Jackson Hole remained virtually untouched and pristine until its first white residents in about 1884. Most of the early settlers put down roots in Wilson or Jackson, so it was unusual to consider what these LDS pioneers did.

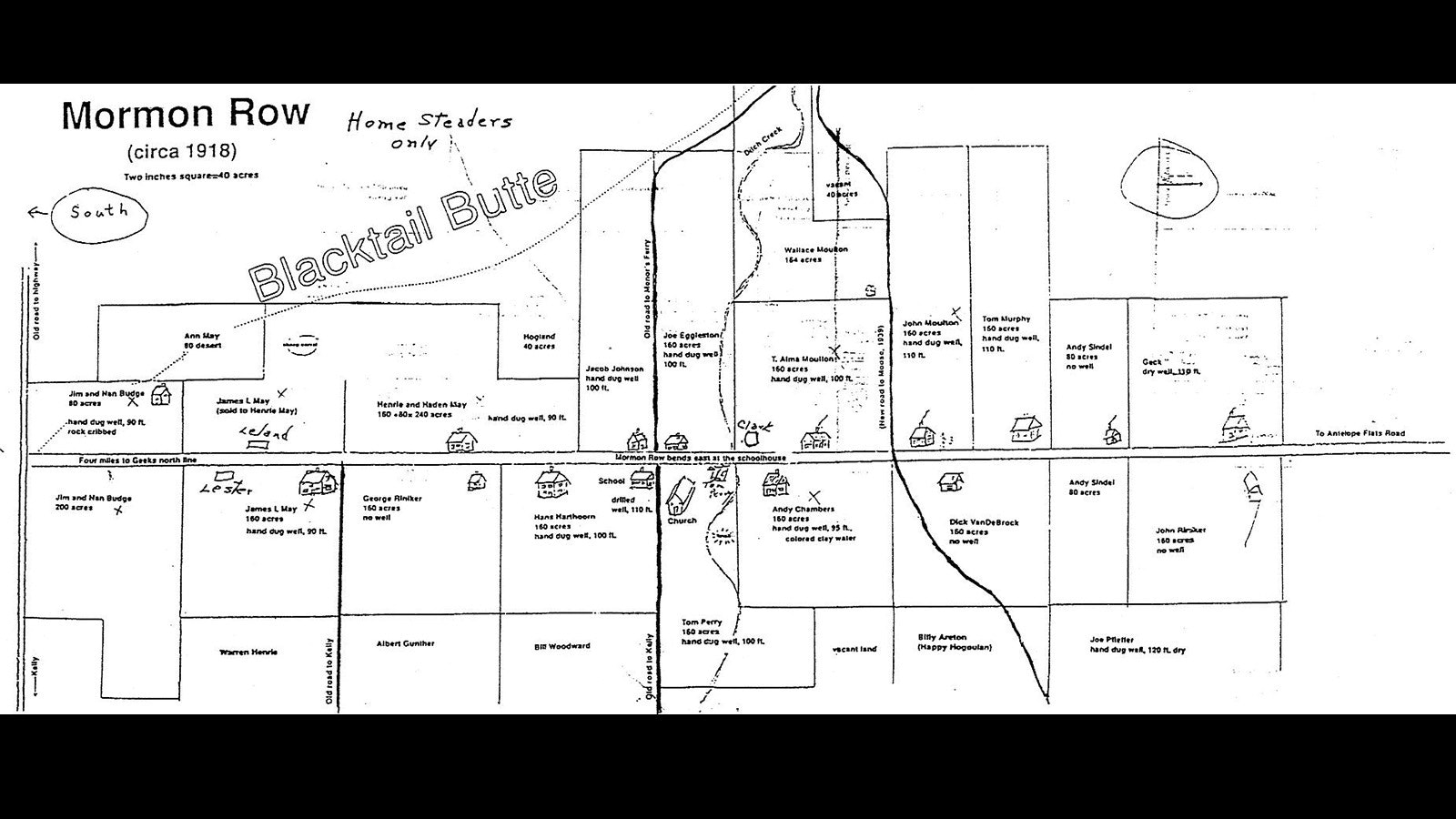

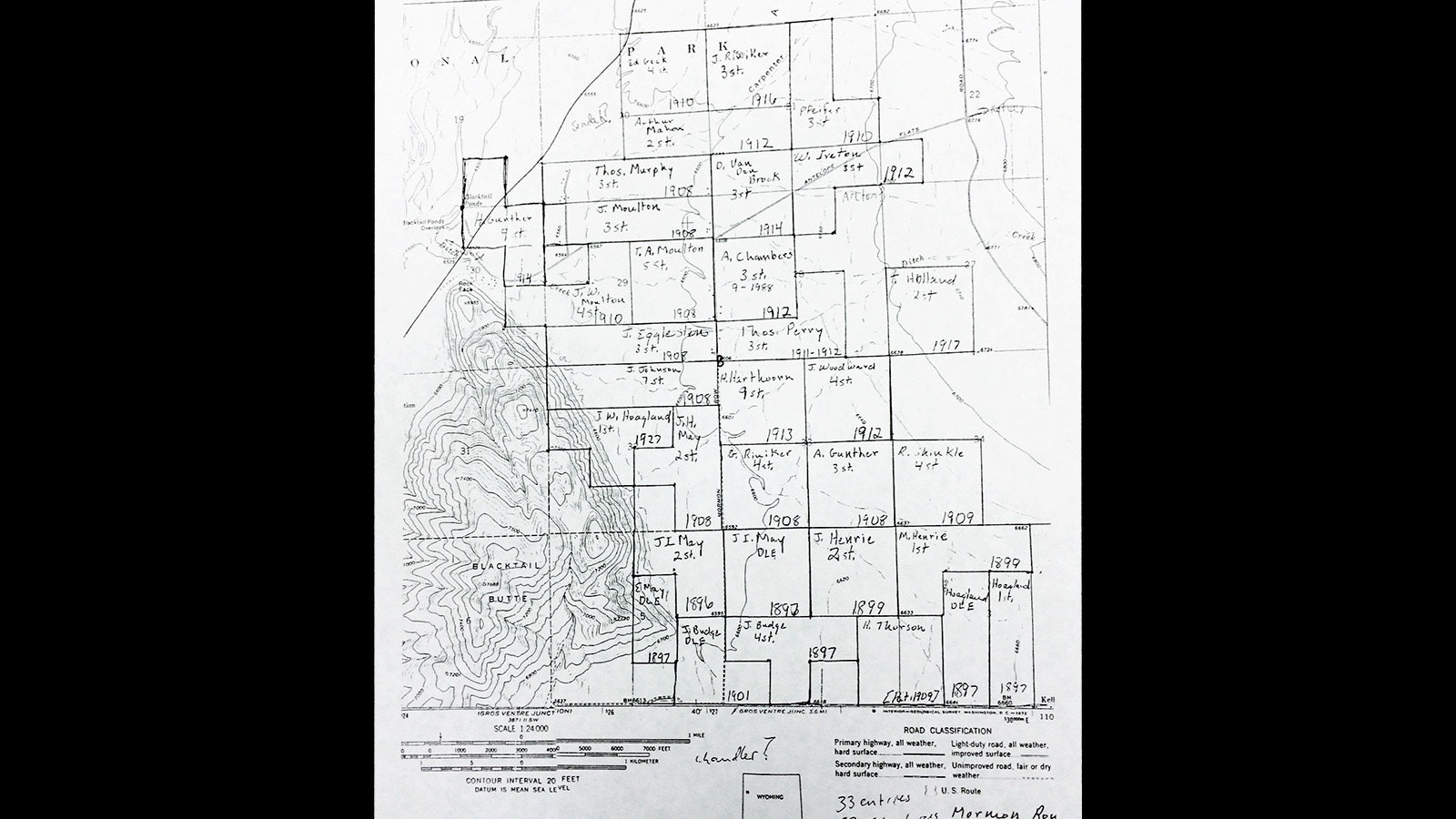

Those original homesteaders arrived in 1896 and created a clustered north-south community lined up along a central road. The fields and agricultural lands were located behind each of the homesteads.

These small communities were built upon communal cooperation, sharing resources and workloads — practices based directly from the Book of Mormon.

Mormon “line villages” such as the one making up the now-defunct town of Grovont were also popularly known as “Mormon rows” throughout the West. The nickname referred to the linear organization of the communities as well as the primary religion practiced.

Initially used insensitively, the nomenclature eventually acquired positive connotations.

Additionally, the faith’s Deseret magazine reports that while the LDS faith is rebranding and moving away from the term “Mormon” in favor of Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the church still considers the term Mormon acceptable “when used as an adjective in such historical expressions as Mormon Trail.”

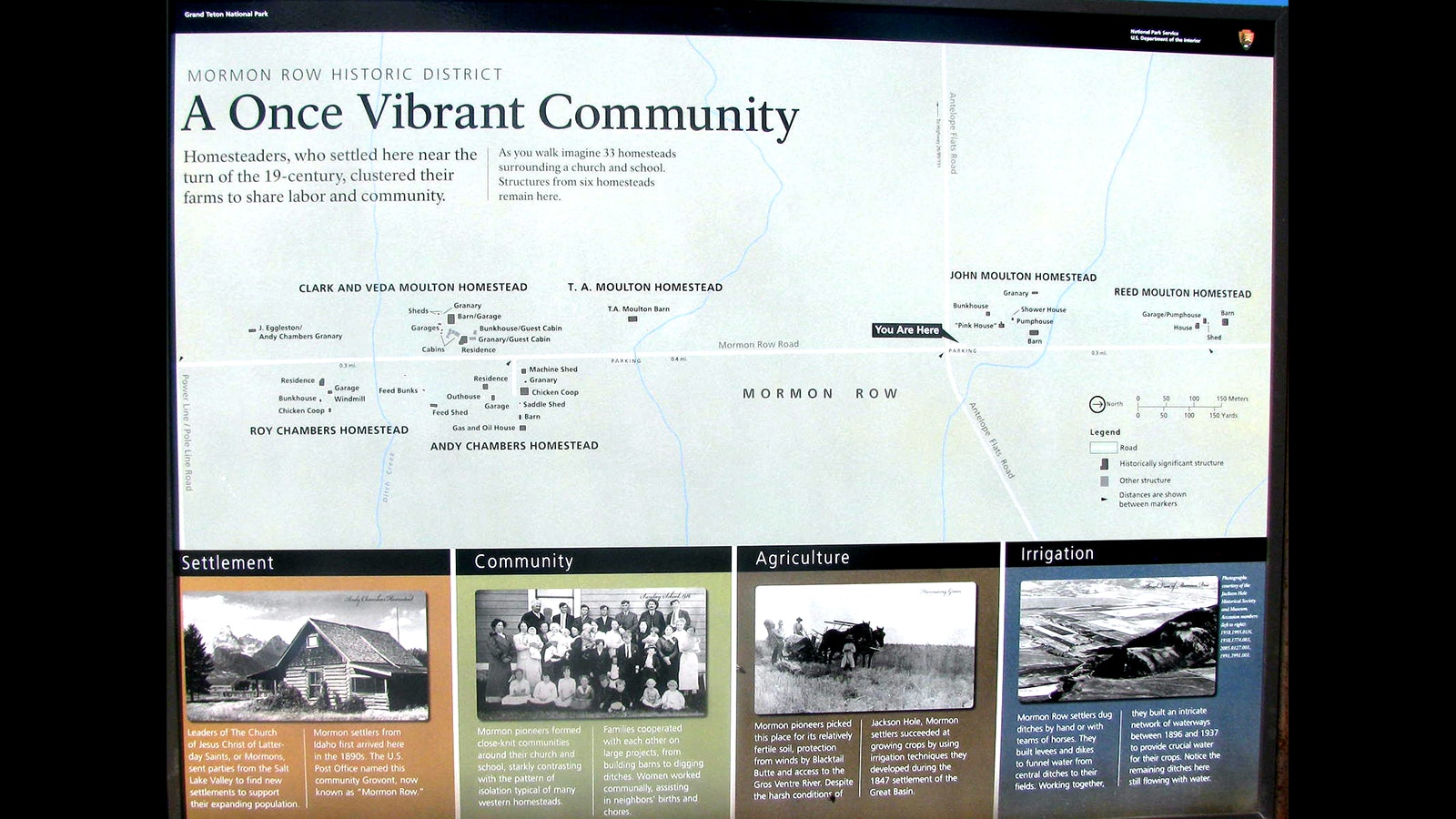

The primarily Mormon homesteaders who settled east of Blacktail Butte near the turn of the 19th century clustered their farms to share labor and community in stark contrast to the isolation typical of many Western homesteads.

Horse and wagon (sleigh in winter) remained the predominant form of transportation throughout Jackson Hole, even long after the introduction of automobiles. This dependence on horses for transportation kept the local cash crop of hay and oats economically viable.

Families grew mainly grew hay and grain crops like 90-day oats that were suitable for high elevations with an average 60 frost-free days a year.

The hardy settlers dug miles of ditches by hand and with teams of horses, building an intricate network of levees and dikes to funnel water from the nearby Gros Ventre River to their fields. Water still flows in some of these ditches.

Farmers were subject to the whims of Mother Nature. Anything from a prolonged drought or a 15-minute hailstorm could mean the difference between barely getting by and bankruptcy.

The unpredictable meteorological nature caused many to diversify — most into small cattle operations. A couple also went into the sheep business despite haranguing from local cattlemen.

Begins With Budge

Let’s take a tour down memory lane known as Mormon Row. Parking at the southernmost end just off Gros Ventre Road, we’ll head north.

The first two homesteads you come to are the first two families to settle in the area soon to be known as Grovont — a phonetic spelling of the nearby Gros Ventre River and its territory. The Budges and the Mays arrived in 1896 and staked their claims shortly thereafter.

That’s Jim and Nan Budge’s place immediately on the left. The 80-acre timber parcel included a one-room cabin built in 1897. While it may have met the requirements of the Homestead Act, it leaked so bad during rainstorms Nan would huddle with her two young ones under the kitchen table and wait it out. Jim added a few more rooms by 1907. No buildings remain today.

Nan ran the Grovont Post Office out of her home for a few years after it opened in 1899. Post office operations subsequently took place at various parcels on the row, including the May and Chambers properties until it closed for good in 1950.

Across the way, to your right, is the Budges’ 200-acre ranchland where they tried their hand at farming. The couple also had numerous horses at all times and Jim would often win prizes at the local rodeo with them.

Nan transplanted yellow roses at her place. They flourished, and soon many of her neighbors also enjoyed the colorful touch.

Jim and Nan raised eight children in Grovont before they sold out in 1941 and moved to Wilson.

Meet The Mays

Keep heading north. Just short of a mile from the parking lot you will reach the May homesteads.

Jim hauled fresh-cut logs from the heavy timber west of the Snake River to build his cabin and barn. Too poor to pay the $1.50 per wagon fee the Menors charged for the ferry, May swam his team across every time he took a load home.

May completed a two-room cabin right away and then ordered carpenters to build him a two-story, five-room house. When it was complete, Jim’s wife Ann insisted they paint the roof blue. The crew had only yellow.

They compromised, using some of Ann’s blue and their yellow to make a sort of seasick green. Ann would eventually turn a decent enterprise selling meals from her home for 35 cents and renting on the occasional room. During construction of the Jackson Lake dam from 1911-16, the May house was the only place to get a room and board from Moran to Jackson.

Meanwhile, Jim added a huge barn and stables by the time he filed final proof papers on his 160-acre tract in 1901. The Mays were able to cultivate only 65 of those acres, the rest being too rocky.

It was also Jim who started the system of irrigation in the Mormon Row area, syphoning water from the nearby Gros Ventre River through a series of hand-dug channels to water the community’s crops.

In the early years, Jim used his teenage son as a night watchman against marauding elk trying to get into his haystacks. Henrie didn’t care for the assignment one bit, out all night with a lantern and a fiddle. But he took to the life and would one day marry a woman named Hadden and settle on a 240-acre spread of his own right next door to his parents.

Theirs is the next property you’ll come to, on the left, on our walk down Mormon Row.

More Mormons

Across the street from Henrie and Hadden May was George Riniker’s place. He came to Grovont in 1908 from Ohio, originally. Rumor had it he ran away from home at a young age bound for Alaska. He made it as far as Montana, then Lander, Wyoming, where he picked up work as a logger.

Eventually, he would make his way to Jackson, meet a girl, and claim his 160 acres in 1909 as soon as he was married. George and Martha didn’t have much money, but they managed to build a small cabin with money he made working on the Jackson Lake dam as a dynamiter.

Like most other families in Grovont, they raised oats and barley along with hay for their stock. Before long, Riniker got into sheep, which did fairly well for him.

George’s older brother, John, would also move to Mormon Row in 1916, the last homestead at the end of the road on the right.

Hans Hawthoorn’s place comes next on the right. Hawthoorn was a hardworking Dutchman who settled in 1913 and allowed the Grovont school to be built on his 160 acres.

George and Martha hit on hard times during the Depression. Banker and real estate developer Robert Miller foreclosed on their place and sold it to Rockefeller.

Miller also bought out John and Ethel after their property was all but washed away in the Kelly flood of 1927.

We are now at the Joe Eggleston and Jacob Johnson properties on the left (west) side of the road.

Joe came to Mormon Row with his uncle Jacob in 1908.

Joe and Jacob appropriated the rights to 4 cubic feet per second of water from Ditch Creek, sufficient to irrigate about 70 acres. Their ditch was known as the Johnson-Eggleston ditch and was 1 foot deep and 4 feet wide.

The Egglestons didn’t last too long. They sold their place in 1919 to a neighbor, Andy Chambers, and moved back to Eden, Utah, where they were from.

The Grovont church is beside the school on the right side of the road. It sits in the southwest corner of Tom Perry’s land on a 1-acre lot he donated to have it built.

Perry came to Mormon Row with his friend and neighbors in Idaho — the Moultons. Perry was a carpenter by trade and helped the Moulton families build their houses.

He also built the church in 1916, which became the hub of the little community. The building was moved to Wilson, but is still marked today by fence posts, two cottonwoods and a spruce tree.

Moulton Era Begins

Now we come to the Moultons of the “barn” fame. Their story traces back to England where Thomas Alma Moulton’s grandparents emigrated from.

Alma (Thomas Alma, or TA, preferred to go by his middle name) became a teenage sheepherder for his parents in Idaho until one day his cousin George got him excited about the Homestead Act and what it could mean about staking his own claim.

In 1907, Alma, his younger brother John, and the aforementioned neighbor Thomas Perry struck out for Jackson Hole. They filed their side-by-side claims in 1908. Brother Wallace joined them a year later, and the brothers worked the combined 480-acre spread as one.

Alma continued to shepherd in Idaho during the winters. He would return every summer to prove up on his place in Mormon Row. By 1912, Alma made the move permanent and brought his wife, Lucile, and their newborn, Clark, to their new home in Grovont. Lucile was not impressed.

But they made it work, improved upon the place, and by 1913, Alma began work on the barn that would live on in antiquity as a symbol of the American spirit and the perseverance of its settlers. All Alma cared about was getting Don and Saylor, his faithful horse team, sheltered during the harsh winters.

The barn is not unique in its architecture in any way. It is fairly typical of most barns from the early 1900s. For years, Alma worked to complete his barn in spurts. He worked when necessity demanded and money allowed.

The TA Moulton barn was complete enough to move animals in and begin getting use out of it by 1915, but it would be three decades before Alma considered it fully built. Meanwhile, he helped his brother John on his barn — the other most famous barn in the world.

When Alma and Lucile’s firstborn, Clark, married Veda in 1936, Alma gave the newlyweds a 1-acre plot in the corner of his homestead. The couple built a house on the property, which still stands.

John and Bartha married in 1917. Bartha was Lucile’s sister. The two met when Bartha came over from Idaho to help with Lucile’s delivery of Clark.

John managed a successful dairy farming business beginning in the 1920s. He sold milk, cream and butter to nearby dude ranches and tourist resorts.

John and Bartha lived in the old original cabin until sometime around 1934-38 when the notorious “pink house” was built.

The story goes that John wanted to surprise his wife upon her return from a brief hospital stay by painting the house. He knew she wanted it repainted, so what better way to commemorate her homecoming than to have the stucco home slathered in an eye-catching salmon pink color.

The color was a mistake — at least that was how John explained it when Bartha first laid disbelieving eyes on it. She reportedly loathed the horrible hue but so loved the sentiment behind it, they kept it.

John Moulton, at the age of 66, sold his place to the National Park Service in 1953 with the condition he could lease it back until his death. Turns out that was quite a while, as John didn’t die until 1990 at the age of 103.

Alma, meanwhile, sold out in 1963 despite his son Clark begging him to hold onto the property. Clark and Veda retired to town in 1987, but refused to sell their 1-acre parcel. The property was passed down to the next generation and recently sold back to the Park Service in 2018, making it the last of privately owned real estate in Mormon Row to be folded into Grand Teton National Park.

Andy Chambers

Andy Chambers was one of the latecomers to Grovont. He snagged the last 160-acre plot there in 1912.

He later married schoolteacher Ida Kneedy on Feb. 23, 1918. Their honeymoon was cut short by Uncle Sam as Andy was drafted into World War I.

When Andy returned from the war in 1919, he got down to the business of raising crops and kids. The Chambers dry-farmed their land, wholly dependent on rain for irrigation. In fact, while most families on the row eventually had wells to service their household needs, the Chambers didn’t dig theirs until 1927.

To make ends meet, Andy picked up the mail route from Jackson to Moran (1932-40) while Ida served as Grovont postmaster from 1923-35. Andy also enjoyed trapping along the Snake River just north of Moose.

Andy had a knack for farming, getting the most out of his land. At one point, the Chambers also ran some 250 head of Herefords.

Chambers was so successful, he managed to buy the adjacent Eggleston homestead in 1919.

Unfortunately, the Chambers’ home burned down in 1936. Ida had to give up the post office as a result and the family moved back into the drafty small log cabin. Andy bought a home in the town of Jackson so the kids could go to high school.

Andy died of heart complications in 1945. His eldest son Roy, two years out of high school, took over management of the Chambers operations and immediately made improvements and brought expansion.

Roy and his brother Reese rigged up a windmill generator to provide electricity to the property. Rural Electric Administration would not get around to supplying juice to Grovont until the mid-1950s when most of its residents had sold out and moved away.

Roy also acquired a modern-day threshing machine for his grain operation. He was joined by the Mays and the Moultons on that venture.

In the late 1940s, Roy purchased the nearby Luther Taylor ranch and the original Thomas Perry land, then owned by Wallace Moulton.

The Chambers’ property is the most extensive historic complex remaining on Mormon Row primarily because the family was still around until 1987 when Roy and Becky moved to town.

The Rest Of The Row

Thomas Murphy had the property adjacent to John Moulton to the north. He filed for his 160 acres in 1908 and received a patent in 1915. He arrived with the Moultons, who were neighbors in Idaho.

Murphy sold out to Joe Heninger in 1920. Heninger had the Jackson-Moran mail route before Chambers (1920-25). He used his large barn to house the mail trucks during the summer, and the horses and sleighs used in the winter.

John Moulton bought Heninger out in 1945 and gave the property to his son and daughter-in-law Reed and Shirley.

Across from the Murphy homestead is Dick VanDeBrock’s place, adjacent to Andy Sindel’s. Both men found their “mail-order” brides using the Heart and Hand Club in Chicago. Both wives did not take well to pioneer living and made their husbands move back to Chicago with them not long after they arrived in Grovont.

Last on the row on the left are the old Arthur Mahon and Ed Geck ranches across from the aforementioned John Riniker spread.

Mahon and Geck didn’t make much of a go on their places and the land was quickly reclaimed by sagebrush. Mahon is believed to have sold out or abandoned his claim. Geck died in early 1918 while in California.

Joe Pfeiffer came to Grovont in 1910 from the copper mines in Butte, Montana. He worked the bare minimum 20 acres of his property bordering Riniker and Sindel at the north end of the row, enough to support the bachelor’s meager needs.

What makes Pfeiffer’s story interesting is he was the community’s unofficial well digger. He helped just about everyone in Mormon Row hand dig their wells for household use, perfecting a method of his own creation.

Ironically, however, while most wells struck water at 90-100 feet deep, Pfeiffer reached 120 feet on his own property and gave up after his efforts produced nothing but dust.

Remaining structures on the Pfeiffer property burned in the Antelope Flat fire of 1994 after decades of abandonment and neglect.

Into The Modern Age

Of the 27 or so families that carved out an existence on Mormon Row, none remain today and little evidence of their plight can be found.

Looking around the deserted sagebrush prairie now — ignoring a Lexus or two in the makeshift parking area — this collection of ramshackle outbuildings and bleached-out foundations is largely how it looked when most everyone left in the late 1940s.

Homesteaders either gave up their claims or sold out to Rockefeller’s Snake River Land Co. and his vision to create Grand Teton National Park.

In 1997, the district was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

In 2021, Grand Teton National Park Foundation launched a multimillion-dollar effort to restore some noteworthy properties in Mormon Row. The Mormon Row Initiative is a $7 million public-private partnership that hopes to revitalize the district and increase its ability to coexist with the area’s natural resources.

About That Quiz

In case you missed it, the first residents of the famous TA Moulton Barn were Don and Saylor, his team of horses.

And Henry Fonda milked a cow named Blossom in the barn while filming the 1963 movie "Spencer's Mountain" at the homestead. Reports from the time say he was't very good at it.

Want to explore more? Check out Candy V. Moulton’s book “Legacy of the Tetons: Homesteading in Jackson Hole.”

Jake Nichols can be reached at: Jake@CowboyStateDaily.com

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.