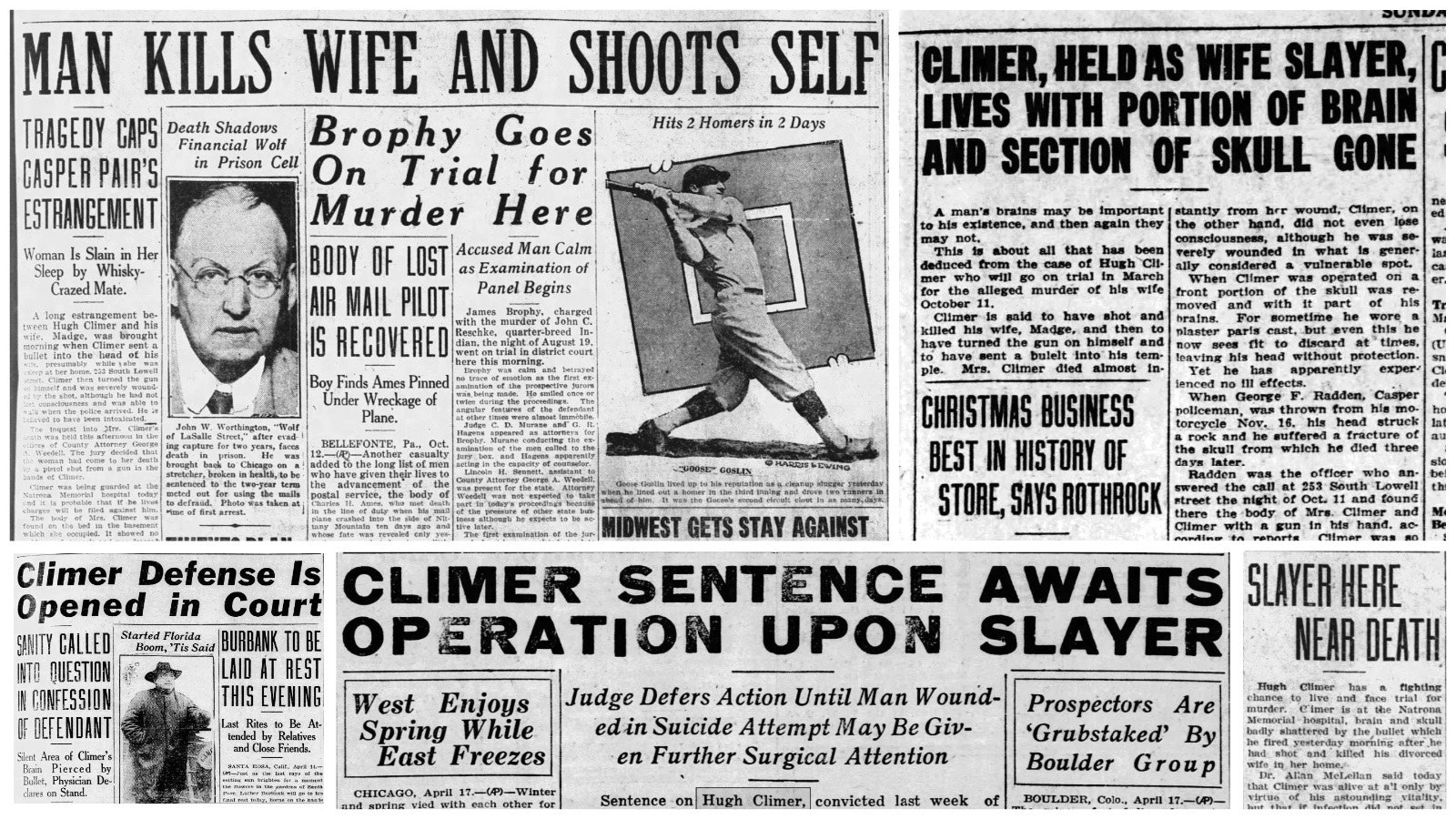

Hugh Climer shot himself in the head with a .38-caliber bullet after he shot his wife.

She died. But Climer was alive enough to reportedly help the police officer who responded to the crime scene get the policeman’s motorcycle unstuck from the mud.

The date was Oct. 12, 1925.

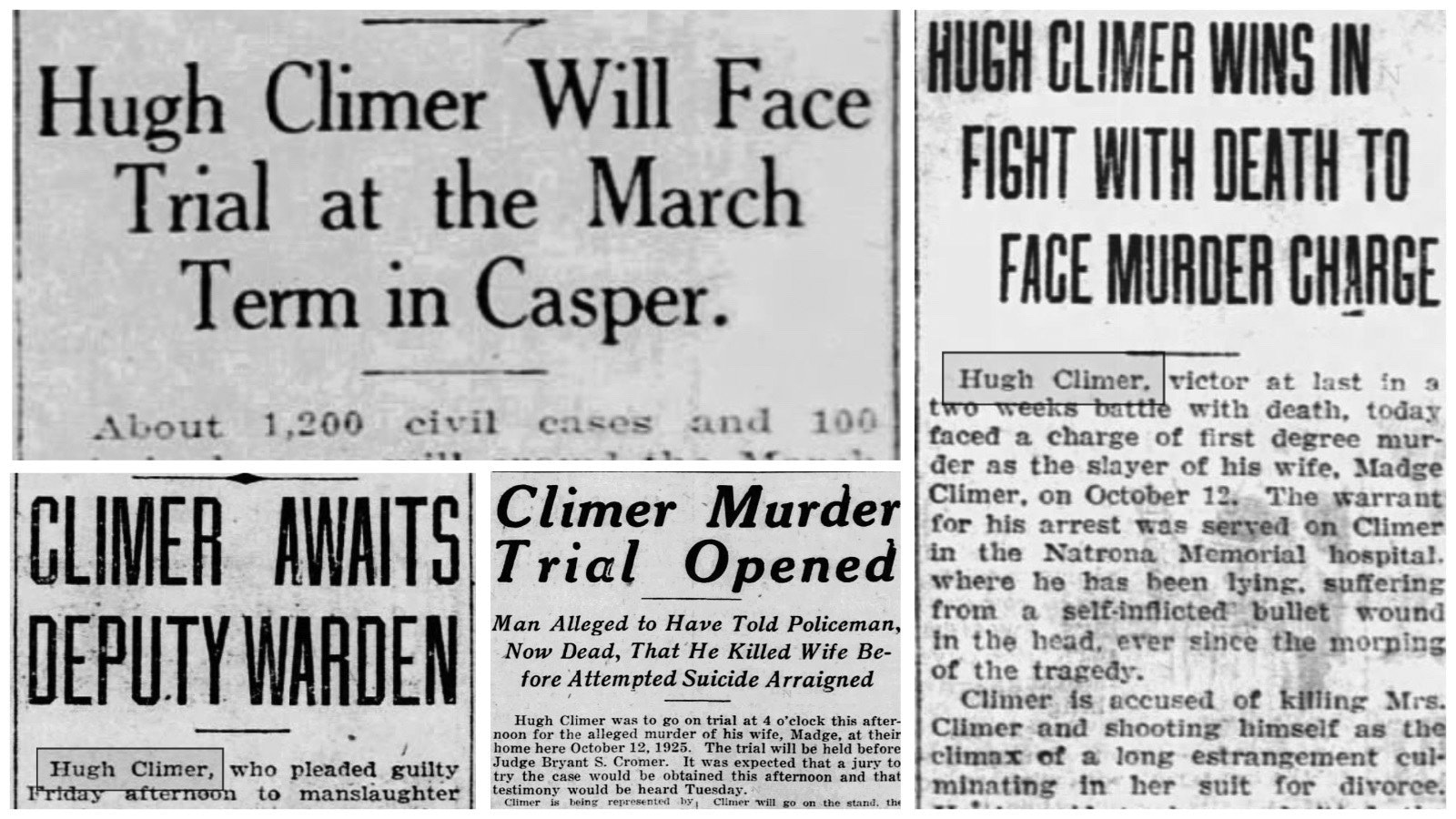

During Climer’s subsequent trial for murdering his wife, he made Casper, Wyoming, history and became the talk of the town.

“Climer will go on the stand, the first man ever to appear in a local court with the entire top of his skull and part of his brain removed,” the Casper Tribune Herald reported April 5, 1926. “Since he was operated on to save his life from a bullet wound, said to have been self-inflicted the night his wife met her death, he has been somewhat an object of curiosity.”

And that is not the only curiosity about the World War I veteran who would go on to serve a prison sentence, be pardoned early, then enjoy friendships and travel after doctors predicted his death more than once.

Tennessee Beginnings

Climer was born in Tennessee on March 13, 1883, and served in an engineering unit in World War I as a cook. He entered the U.S. Army on Nov. 1, 1917, at Fort George Wright in Washington state and was separated June 5, 1919, at Fort D.A. Russell in Cheyenne. The fort is now known as F.E. Warren Air Force Base.

He married Jan. 25, 1923, in Spokane, Washington. By September 1925, the couple was in Casper and Climer’s marriage to Madge was on the rocks. The Casper Tribune Herald reported that a local judge had issued a restraining order against Climer and that his wife had filed for divorce.

“Mrs. Climber declares in her petition that her husband is possessed of a violent temper, and he is liable to do her great bodily injury,” the paper reported. “She charges cruelty and non-support as grounds for divorce and says that three months after she and her husband were married, he tore up the marriage certificate.”

In October, just a month after the restraining order had been issued, Climer, 43, tried to reconcile, an effort that obviously didn’t work.

Early in the morning Oct. 12, Casper Police Department Officer George Radden was called to the scene by a couple living in the upper story of a house where Madge Climer lived in the basement. The neighbors had heard two gunshots.

The Casper Tribune Herald reported Radden responded to find the basement filled with smoke, heard a noise and shouted, “Come on out.”

‘Bad Gash’

Climer staggered out with a “bad gash on the temple,” according to the newspaper. Radden found Madge Climer’s body, bed and clothing covered in blood.

“I only fired once,” Climer allegedly told Radden. But the weapon showed two bullets had been fired. The coroner was called and Radden saw that Climer needed medical attention. He put him in the sidecar of his motorcycle.

“When he was unable to get the machine started out of the mud, Climer himself got out of the sidecar and pushed the machine out,” the Tribune Herald reported.

Climer was taken to the hospital and doctors found a bullet had entered his brain an inch in front of his right ear. It came out over the left eye, shattering the front part of his skull. They operated, removing part of his skull and part of his brain. He would remain in the hospital for 16 days and received treatments for two months after that.

Just more than a month after the shooting, Radden died as the result of head injuries he received in a motorcycle crash. His testimony would have been important for the prosecution’s chain of evidence in Climer’s murder trial.

The Trial

Climer’s trial for murder was the following April in 1926. During testimony, the defense questioned admitting into evidence an alleged confession made to the coroner, who spoke with Climer at the house after the shootings.

When the defense introduced its witnesses, Climer’s initial examining physician at the hospital was called to the stand.

That’s when the jury got to see just what Climer had done to himself after killing his wife.

“Climer’s head, which has been covered by a white cap or by a bandage during the trial, was shown to the members of the jury this morning when Dr. McLellan removed the covering,” the Tribune Herald reported. “The peculiar contour resulting from the removal of the fore portion of the skull and brain had been hidden from spectators up to this time.

“Climer left his head uncovered when he turned away from the jury and walked back to his seat, giving the spectators in the courtroom an opportunity to observe the shape of his head. He replaced his cap, which he has been wearing during the last few days, when he again took his chair beside that of his brothe,r who has been with him through the trial.”

Dr. McLellan told the court that the wound to Climer’s head meant statements made by Climer at the time of the shooting could be “rational and credible,” but also “that he might be untrustworthy.”

“One would have to weigh them considerably,” the doctor said, telling the court that he had questioned Climer at the hospital shortly after the shooting and that “the man’s answers were negligible. He had given an affirmative answer when asked if he had been shot.”

Whiskey Involved

Climer took the stand in his own defense and told the jury that he was trying to reconcile with his wife and she had asked him to buy whiskey. He had had four to six drinks and she had downed the rest. Two empty bottles were recovered from the scene.

Climer testified that the couple decided to reconcile and he had left the bedroom, then returned and received a blow on the head and couldn’t remember any other events.

The jury would return a guilty verdict of manslaughter, despite no instructions on that verdict from the judge. The verdict was overturned, and it was determined a new trial was needed.

Guilty Plea

In August 1926 before the second trial could begin, Climer, encouraged by his brother William, who arrived from Armstead, Montana, pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to 12 to 18 years in the state penitentiary at Rawlins.

The newspaper called it a death sentence.

“This virtually means a life sentence, according to the physicians’ verdicts that Climer will probably not live more than five or six years at the most,” the Tribune Herald reported.

In January 1930, after four years in prison, Climer’s name appears in newspapers again with a request for a parole. It was granted in April of that year and Climer was paroled to the custody of his brother.

“He is in need of specialized medical attention, which cannot be given at the penitentiary, that relatives might have him treated to save his life,” the Casper Tribune Herald reported April 6.

It didn’t take Climer long to start a new life away from Casper and the notoriety of his wife’s murder and a sensational trial.

On July 4, 1930, the Dillon Tribune in Dillon, Montana, mentions him in its social columns: “Hugh Climer, of Armstead, attended to business matters here Saturday.”

Climer’s older brother and benefactor William died March 29, 1932, in Beaverhead County, Montana.

Trip To France

Turns out, those doctors who predicted no more than five or six years of life left for the man who shot himself in the head and survived were off by a few decades.

Newspaper accounts in later years continue to mention Climer in social pages. The Butte Daily Post in Butte, Montana, on July 26, 1935, reported that Climer was “visiting friends from his home in Wyoming.” On June 1, 1939, he’s mentioned as among eight Dillon, Montana, men “returning from France this month.”

The former convict, murderer and man with a big dent in his skull missing part of his brain had apparently found a new life. One newspaper mentions he worked for the P&O Ranch in Montana. He would outlive all of the predictions and prophecies of the medical profession.

He spent the last 10 months of his life in late 1953 and 1954 hospitalized. He died Aug. 28, 1954, in the veteran’s hospital at Fort William Henry Harrison in Montana.

The Montana Standard had a two-paragraph story on his death.

“Graveside services took place Saturday afternoon in Legion plot in Mountain View Cemetery for Hugh Climer,” the paper reported. “Old-time friends served as pallbearers.”

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.