Federal prosecutors have been charging. Jan. 6, 2021 protestors with a 20-year-felony that Congress originally crafted to combat evidence shredding in corporate fraud cases.

The federal government and a lower court both say the law is broad enough to apply to the protestors.

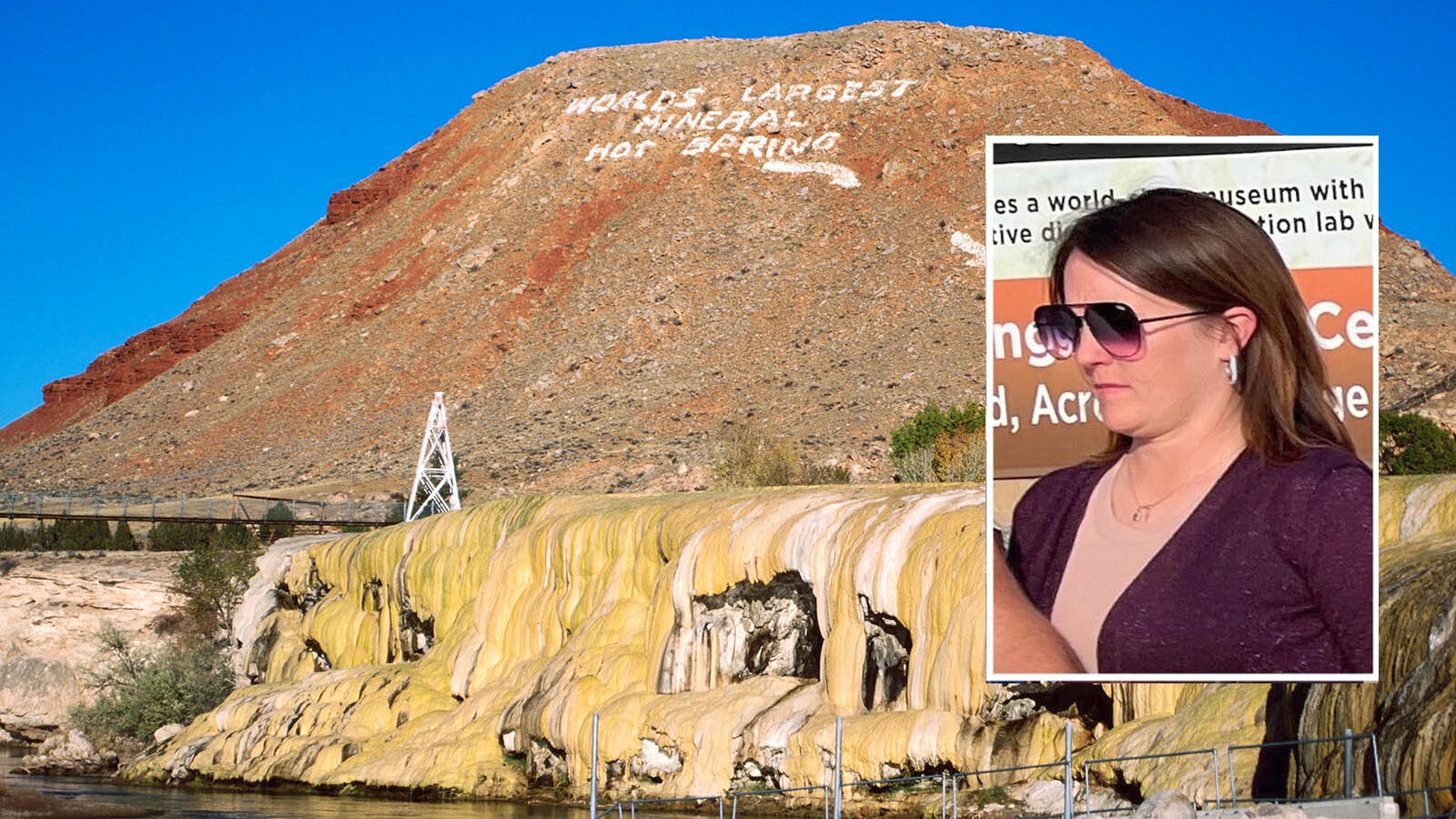

Wyoming's Republican U.S. House Rep. Harriet Hageman and 21 others in Congress countered, urging the U.S. Supreme Court on Monday to overturn the lower court's broad interpretation.

Could Affect Hundreds, Plus Trump

The U.S. Appeals Court for the District of Columbia ruled last April, in a 2-1 decision to let federal prosecutors charge pro-Trump protestors with a 20-year felony that Congress originally passed to combat evidence tampering in corporate fraud cases.

Hageman and her peers argued in a Monday amicus brief to the U.S. Supreme Court that such a broad reading of the law criminalizes political conduct and spawns one-sided witch hunts.

This counters the federal government’s earlier argument to the Supreme Court, in which the government pointed to what it describes as a catchall in the statute: the word “otherwise.”

The first part of 18 USC 1512 (c) bans the shredding of evidence needed for an official proceeding.

The second part, leveled against defendant Jim Fischer and other Jan. 6 defendants, includes anyone who “corruptly… otherwise obstructs” official proceedings.

The government said the word "otherwise" should criminalize all obstructions of official proceedings, not just evidence shredding.

The high court’s decision in this case could affect former President Donald Trump, who is charged under the law it is now reviewing. It could also affect more than 100 Jan. 6 defendants charged under that statute.

Here Are Your Handcuffs

Jim Fischer entered the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

According to his argument to the high court, he walked into an unfenced Capitol building, got knocked to the ground by the crowd, handed a pair of handcuffs back to a Capitol police officer who had dropped them, then got pushed into the police line and pepper-sprayed into temporary blindness.

Fischer’s court documents describe his actions as “nonviolent” and say he was within the Capitol building for fewer than 4 minutes.

A grand jury saw his conduct differently, indicting Fischer on seven charges, including assault of an officer, disorderly conduct and picketing in a Capitol building.

The U.S. Attorney then added the 20-year charge accusing Fischer of “corruptly” obstructing a Congressional proceeding.

A New Door To Prison

Hageman and the other delegates’ brief argues that the D.C. Circuit broke the rules of reading laws.

The appeals court declared the “otherwise” law unambiguous, meaning it didn’t have to rely on the law’s legislative history to fill in its vague areas.

The dissenting Judge Gregory Katsas disagreed with that reading. He pointed to the law’s origin as a response to the Enron fraud scandal of the early 2000s, and said it “covers only acts that impair the integrity or availability of evidence.” Top culprits in the Enron case, which resulted in what was then the biggest bankruptcy in American history, destroyed documents proving their fraud.

Hageman’s brief accuses the federal government of magically discovering new prosecutorial tools no one has ever recognized before, in a 22-year-old law.

“Typically, when the government claims to have ‘discover(ed) in a long-extant statute an unheralded power’ (like) charging trespassers with a 20-year felony — a court should ‘greet (the government’s) announcement’ of this new authority ‘with a measure of skepticism,’” says the brief, quoting from earlier case law.

Imprisoning Trumpers

A broad reading of a criminal statute empowers the government to use that statute to lock up political foes and dissidents, says the brief.

Trump is charged with the same crime Fischer faces.

“Only a clear rebuke from this Court will stop the madness,” says Hageman’s brief. It argues that the broad reading could outlaw lobbying, protest, advocacy and other government influencing.

Activist groups often organize campaigns to flood congressional offices’ phone lines and websites. They’ll also march on Washington during pivotal proceedings, says the brief, citing the 1963 civil rights March on Washington ahead of the Civil Rights Act’s passage.

“The government’s construction would allow any enterprising federal prosecutor to charge Section 1512(c)(2) – with a maximum penalty of 20 years in prison – for anything deemed to have sufficiently affected almost any aspect of the federal legislative or executive functions,” says the brief. “Informal lobbying and grassroots activities against some legislative or executive goal of the President would be subject to a serious felony charge.”

The Government Says ‘Otherwise’

The U.S. government disagrees with these qualms.

The federal government’s October brief to the high court argues that confining the “otherwise” provision to document shredding is “implausible” and would undercut Congress, which is “more than capable of limiting the reach of an obstruction statute to ‘document-related misconduct when it wishes to do so.’”

In other words, if Congress had wanted to limit that statute to document shredding, it would have done so plainly, according to the federal government’s brief.

The government also disputes the Hageman coalition’s complaint that the D.C. Circuit undermined the statute’s legislative history.

Though the appeals court determined the law was unambiguous and therefore the two judges in the majority didn’t have to involve the legislative history in finding its plain meaning, the majority explored that legislative history anyway, and found “nothing … inconsistent” with the broader interpretation of the law.

Who’s Corrupt?

Hageman and her colleagues clash with the federal government on whether the court’s definition of “corruptly” is enough to constrain it from waging a political witch hunt.

The statute specifies that for it to be chargeable, the person obstructing government proceedings had to do so “corruptly.”

Often, criminal laws are fine-tuned by state-of-mind provisions like this one.

One of the majority judges said the definition of “corruptly” should include actions that are “independently unlawful.”

In other words, it is illegal to intend to break the law while breaking the law.

“This is circular,” says Hageman’s brief.

Another judge from the D.C. Circuit defined “corruptly” as intending to procure an unlawful benefit. Overturning the 2020 presidential election results was that unlawful benefit in this case, reasoned the circuit judge.

Hageman’s brief also calls that definition “inherently circular in the context of political advocacy, which by definition seeks to obtain the change for which the person has advocated.”

And Immoral

A third definition of “corruptly” ventured by a D.C. Circuit judge in the majority is with “wrongful, immoral, depraved, or evil” intent.

Hageman’s brief likens this to a pandora’s box — a way for the federal government to charge protestors motivated with any ideology with which the government disagrees.

The brief cites the dissenting D.C. judge, who wrote: “Imagine a tobacco or firearms lobbyist who persuaded Congress to stop investigating how many individuals are killed by the product. Would the lobbyist violate (this section) because his conduct was ‘wrongful’ or ‘immoral’ in some abstract sense?”

Hageman’s brief adds: “In today’s polarized age, many view those with different political beliefs as being immoral or evil.”

That’s especially true between Trump-lovers and Trump-haters, the brief adds.

Also These Delegates

The other delegates signed onto Hageman’s brief are:

Senators: Tom Cotton, Arkansas; Kevin Cramer, North Dakota; Mike Lee, Utah

Representatives: Jim Jordan, Ohio; Cliff Bentz, Oregon; Lauren Boebert, Colorado; Jerry Carl, Alabama; Michael Cloud, Texas; Matt Gaetz, Florida; Lance Gooden, Texas; Marjorie Taylor Greene, Georgia; Diana Harshbarger, Tennessee; Lisa McClain, Michigan; Mary Miller, Illinois; Alex Mooney, West Virginia; Barry Moore, Alabama; Andy Ogles, Tennessee; Bill Posey, Florida; Guy Reschenthaler, Pennsylvania; Matt Rosendale, Montana; Tom Tiffany, Wisconsin; Michael Waltz, Florida

Clair McFarland can be reached at clair@cowboystatedaily.com.