Original documents from Wyoming’s deadliest train wreck fired up Casper historian and steam locomotive engineer Con Trumbull to investigate his own interpretation of the Cole Creek disaster that happened a century ago.

Trumbull’s book “Steam, Steel, and Silence, The Story of the Cole Creek Train Wreck” was published in September, just in time for the 100th anniversary of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Train No. 30 from Casper to Denver that collapsed into a roaring creek bed between Casper and Glenrock on Sept. 27, 1923.

“This wreck is important to the state’s history because it is the worst railroad passenger wreck in the history of the state of Wyoming,” Trumbull told Cowboy State Daily. “It was unusually bad weather, it was in the night, in the dark, it was worse than any wreck down along the Union Pacific or anywhere else in the state.”

Trumbull believes 31 people died, but circumstances surrounding the wreck made getting a definitive number difficult. Four bodies known to be on the train were never recovered. The body of an “unknown male” also was recovered.

And a century after the fact, Trumbull also dredged up information that points to a potential murder plot unrelated to the wreck.

Author And Locomotive Engineer

In addition to being the book’s author, Trumbull also is train master for the Nevada Northern Railway in Ely, Nevada, that features steam locomotives and excursion trains on 30 miles of track.

He understands what it’s like to sit in a steam locomotive from the engineer’s seat and stare at the track ahead with the engine’s headlight piercing into the darkness as the steam, noise and elements add to one’s perception.

Sitting in that seat a century ago at 8:30 p.m. was a replacement engineer named Ed Sprangler, Trumbull said, because the regular engineer “called off” on the route. A young man, Ollie Mallon from Greybull, rode in the cab beside him. As the fireman on the oil-fired locomotive, his job was to ensure the efficiency of the oil burner as well as correct water levels.

On the train were local passengers headed back from Casper to Glenrock and Douglas after a day of shopping and business. There were also salesmen headed to Denver, and a man by the name of Charles Guenther who was an up-and-coming young politician, oilman and philanthropist from Douglas.

“Unfortunately, his story ended before it could get going,” Trumbull said.

It was the examination of the people on the train that provided the most surprising revelations.

“There was also a federal narcotics agent named Doc Chipley who had been collecting evidence against a narcotics ring in Casper. And a strange man follows him onto the train … and they couldn’t find anything about him, and the investigation concluded that he was most likely on the train to rob or kill the narcotics agent to keep the evidence from getting back to Cheyenne.”

Albert Hill’s Story

Trumbull also found the story of a deceased young Black man Albert Beverly Hill, who had moved to Casper and was working at the Chicago and North Western Railroad roundhouse to support his family. Trumbull’s research shows that when claims were being paid out to families of victims in the wreck, the railroad used race to keep his settlement low. Efforts to prove Hill’s work ethic and support eventually garnered his family a $5,000 settlement.

For comparison, the settlement for Guenther’s death was $22,500.

Trumbull said his research project on the disaster began when he received a call from the Western History Center at Casper College. Folks there told him they had a box of documents from the official railroad investigation. He knew much has been written about the wreck, but not about the people involved.

“It had files on all of the people on the train that were impacted, so I was able for the first time to compile the best list of everybody that was on the train, as well as what happened to them, their firsthand accounts, what their injuries were, what they got paid out at the end of the day and where they were traveling,” he said. “It really dived into the people, and it was such a cross section of central Wyoming society that it was amazing to put all of that together. One of my favorite parts about the book is at the end, an appendix that lists all the people for the first time.”

Passenger Numbers

At the time, Trumbull said there were railroads all over the state and for Casper, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy was one of the main ones. He said that on the fateful night, he believes 69 passengers joined 10 crew members on the overnight train to Denver. The actual number of passengers is “hotly contested.”

“The thing is, we don’t really know,” he said. “The conductor’s records were washed away, a lot of people didn’t get on the train that were supposed to, they never did find all of the bodies,” he said. “So, the actual number of people on the train we are never going to know for sure.”

Cole Creek, just inside the Converse County line from where it borders Natrona County, was typically dry. But days of rain and then snow led up to that day. Prior to the disaster, a railroad worker had inspected the bridge.

Yet, the wreck investigation would discover a natural dam upstream had broken just prior to the arrival of the train and unleashed a torrent of water at the bridge creating 12-16 feet of water surging within and over the creek’s banks.

While some speculate the bridge was weakened, Trumbull concludes the bridge was taken out because the passengers felt the jolt of the engineer applying the emergency brakes.

After the disaster, the swollen waters of the creek carried bodies, mail and train debris into the North Platte River.

“A lot of the mail went down the North Platte and pieces of the train were washing up in Douglas and as far down as Guernsey,” he said.

After boarding in Casper, Trumbull said a lot of the male passengers went to the smoking car, which was located right behind the mail car, baggage car and engine. Also part of the train were two coach cars with seats, and two Pullman cars and a Pullman crew. The Pullman crew included a conductor. There was a separate conductor for the train.

Pullman accommodations meant a private contractor “operated a hotel on your train,” he said.

Three Bumps

Accounts show several passengers in the sleeping cars had crawled into their bunks. When the train arrived at the creek without a bridge they reported “three bumps.”

“Bump No. 1 was when the engineer threw the emergency brake. Bump No. 2 is when the train went off the track, and bump No. 3 was when it crashed into the stream,” Trumbull said. “What amazed me reading the firsthand accounts from the time, with the exception of one person who was the ‘over-the-top’ witness, everyone else commented on how quiet it was. It was so sudden and so devastating that there weren’t even any screams.”

Trumbull said the locomotive and the first five cars — the baggage car, mail car, two coaches and sleeping car — all ended up in the water. Passengers in the last two cars were spared a plunge into the water and were the “lucky ones.” Most of those who died, did so immediately.

The train’s conductor, Guy Goff, died and Pullman conductor Lemont Coburn took control of the train and helped rescue survivors in the stream and got them into one of the two remaining cars on the bank. Survivors headed down the track to find help and call the wreck in. A rescue train with doctors and nurses was dispatched from Casper, along with tools rescuers could use to free people from the wreckage.

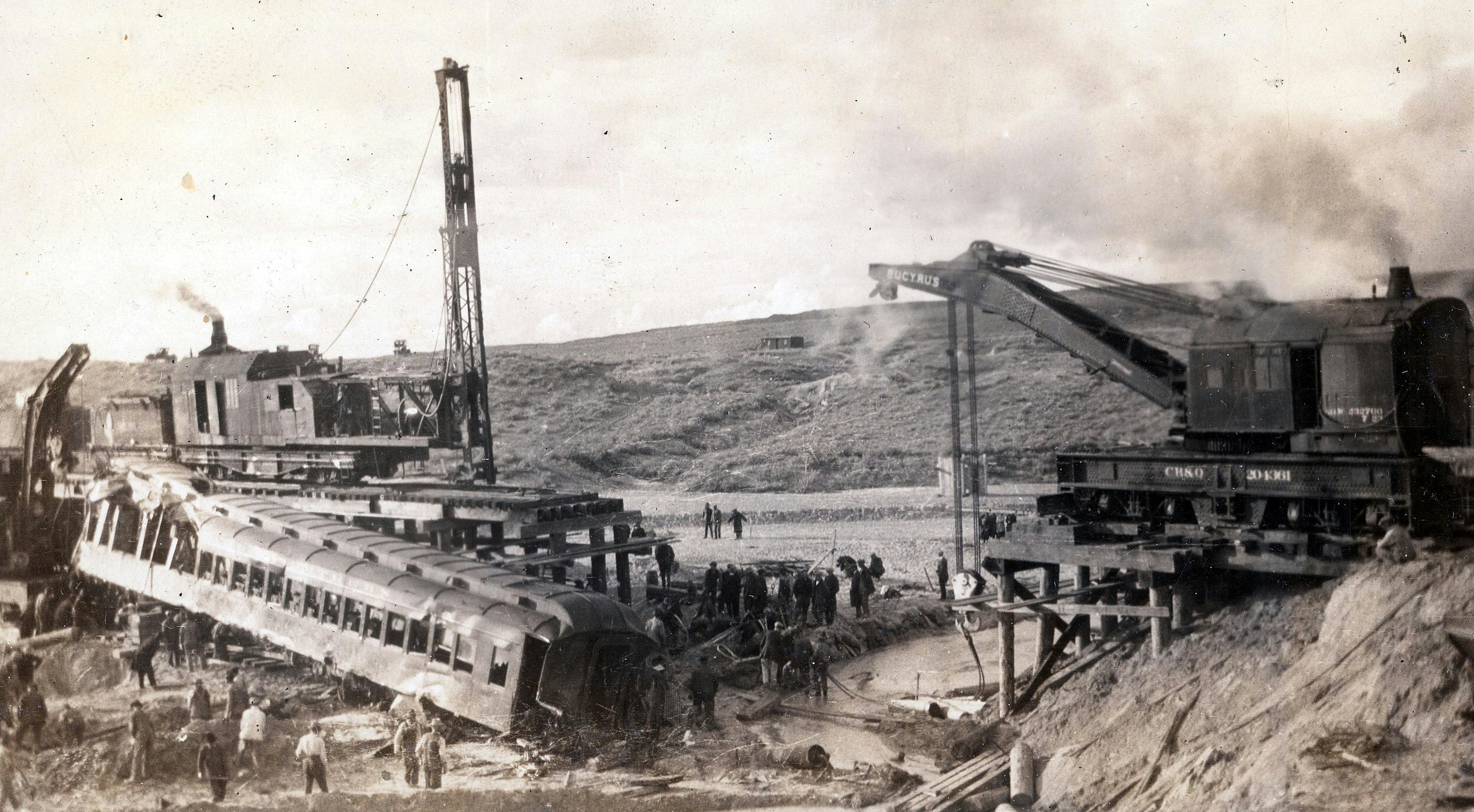

Locomotive Swallowed

Rescuers arrived to find the bridge gone, the water roaring and that the sandy bottom of the stream had “just swallowed the locomotive.”

“The passenger cars landed on top of it, and it took them days and days to dig down to it,” Trumbell said.

Passengers were suffering from shock. One passenger in a car that landed on top of the locomotive as it was sinking into the stream was severely scalded by steam.

Those in the cars behind suffered fairly minor injuries, Trumbull said. The very last car of the train managed to stay on the track, so the rescue train used that car to haul the injured and survivors back into Casper.

“It took years for the full cleanup,” he said. “Within a week, they had a temporary bridge built and they had service going again, but it took them years to put a permanent bridge back into place and completely clean up the wreck. It was quite a mess.”

The engineer’s body wasn’t uncovered until two years after the wreck when crews were installing the new bridge and driving pylons, Trumbull said. The last remains attributed to the wreck were found in the river during the 1950s.

Investigations found the railroad could have done nothing to prevent it, railroad personnel had inspected the tracks earlier and everything was fine. It was called an “act of God.”

“A few years later there was another wreck with exactly the same situation in Montana,” Trumbull said.

From Coal Mines To Shoveling Coal

Trumbull, 35, is a fifth-generation Wyoming resident who has a degree in geology and worked as a coal mine inspector. In 2016, he started volunteering at the Nevada railroad, learning about steam train operations and working on the train. In 2019, he left his mining job.

“I left my job with the federal government inspecting coal and started throwing coal in the firebox,” he said. “I worked my way up from student brakeman, like everyone else who starts out here, and I am currently the train master in charge of operations.”

He also is the author of a book on central Wyoming railroads, co-author of a book on Casper’s history and author of a children’s book.

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.