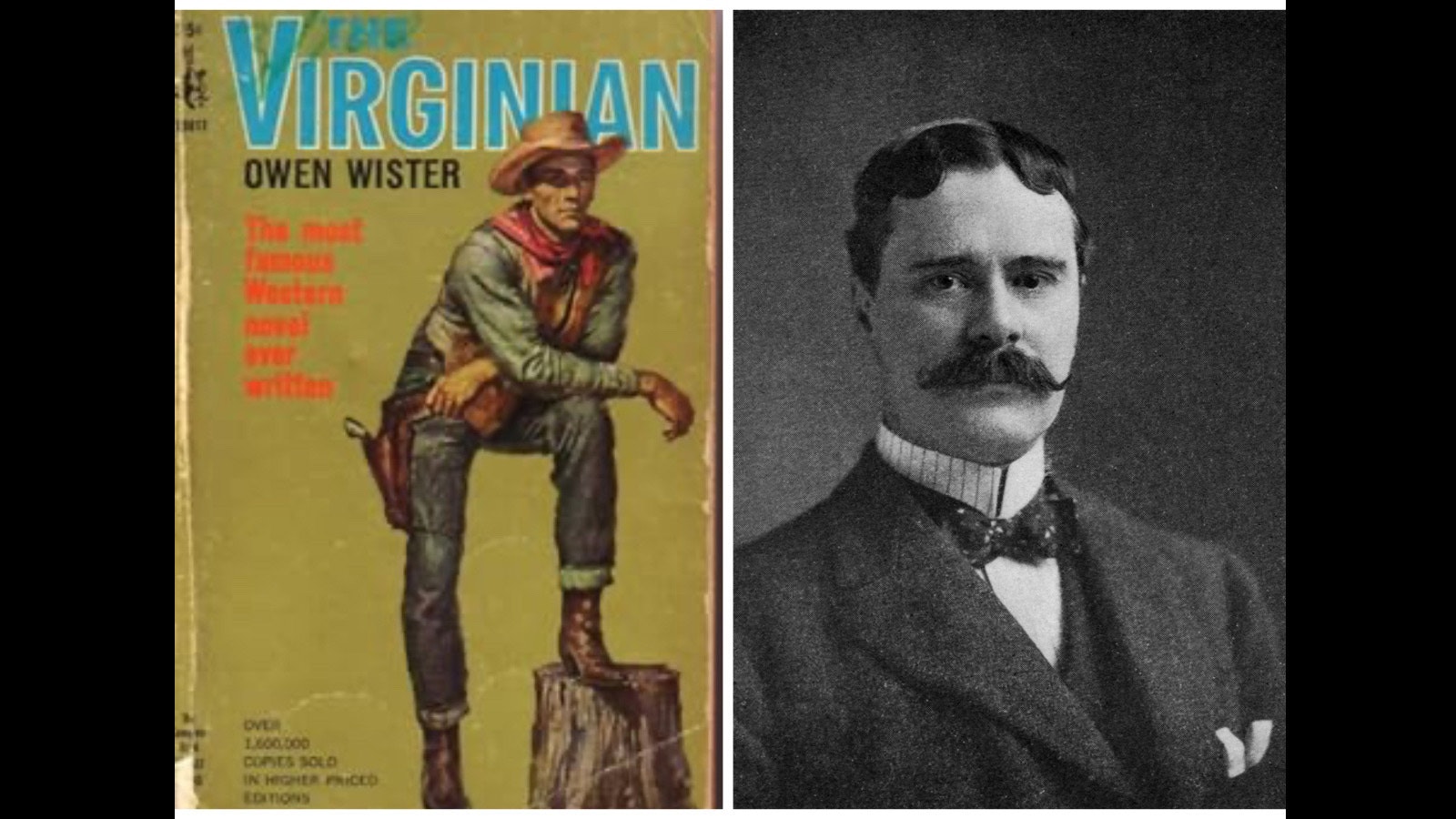

Wyomingites have been playing a guessing game since Owen Wister wrote his blockbuster Western novel “The Virginian” in 1902, trying to figure out who was really the inspiration for the book’s main character.

The Virginian is never named in Wister’s story, but is always this rather mysterious and romantic fellow who is referred to as the Virginian throughout. Wister himself refused to ever say who he based the Virginian on, and many have concluded the character was a composite of cowboys Wister met while in Wyoming.

But now a researcher in Thermopolis has uncovered intriguing oral history preserved in the Hot Springs County Museum & Cultural Center, that may shed new light on some specific people who may have been part of that composite.

‘It Stopped Me Right There’

Thermopolis Tourism Director Jackie Dorothy has received a grant from Wyoming Humanities Council to dive more deeply into these oral histories after she discovered an old manuscript by chance one day, gathering dust on a bookshelf.

“We were putting books back one day, and I was just skimming through it when I came across one of the Wister stories, and it stopped me right there,” Dorothy told Cowboy State Daily. “And it grabbed me because here’s some history that relates to (Wister’s book) on a national and even international level, because ‘The Virginian’ is known throughout the world.”

Dorothy is using the humanities grant she received to prepare a series of stories unpacking these oral histories on her weekly podcast Pioneers of Outlaw Country, which has a new episode each Thursday. She’s also going to be available to do educational presentations for Wyoming schoolchildren on the unique history she’s found on Wister’s most famous work.

Dorothy told Cowboy State Daily she’s found many eye-opening and interesting stories, as told by people from Thermopolis who were close to Wister when he was in Wyoming.

She’s compared those stories with Wister’s own diaries and cross-referenced with other known historical facts to put the oral histories she’s found into the right context.

“The dates in the stories, and the locations, all of it just kind of fall into place,” Dorothy said. “And it’s been really fun, just piecing it all together, and saying this is, you know, what people talked about then.”

Oh, Those Thermopolis Cowboys

Dorothy believes Thermopolis might have something of an edge when it comes to guessing who really inspired the book’s main character, the mysterious “Virginian.”

Some of Owen Wister’s best friends at the time were Thermopolis-area figures, Dorothy said. It turns out that their stories about Wister have been preserved for all time in a thesis on Thermopolis folklore that was written by Sister Mary Krass, as well as oral histories collected by Dora McGrath. The latter is Wyoming’s first female senator and is the founder of the Hot Springs Museum.

“That’s one of the cool things about this is how closely related the history is,” Dorothy said. “This is not great-great-grandchildren. It’s grandchildren. Their grandfather knew Owen Wister, their grandmother relates the story.

“It’s still all up in the air, because Owen Wister didn’t come out and say this was who these people were, but I can at least tell the stories of the people that he knew and met.”

Among the stories Dorothy has uncovered are tales from Elizabeth Short, who at the time was known as Wister’s “best” girl. She went with him to all the government dances at Fort Washakie and other places, as well as stories from Mary Merrill, who also knew Wister while he spent time in Thermopolis.

“(Short) actually got a first edition of his book when it was released,” Dorothy told Cowboy State Daily. “And she says, ‘Well, I know who the characters are. Like the Chalk guy was an actual character, and some other people in the book, Trampus, for example, were real.’”

That first edition book is among artifacts available at the Hot Springs Museum in Thermopolis.

It was also Short who introduced Wister to his main guide in Wyoming, George West, who in turn introduced Wister to Chief Washakie’s son, Dick, another of Wister’s friends and guides while he was in Wyoming.

“Wister got to know both of them well because they camped out together for months,” Dorothy said.

As part of her research, Dorothy also found a book, available at the Hot Springs Museum, that is about Butch Cassidy. That book contains information about Wister crossing paths with Cassidy long before Cassidy would become known as a notorious outlaw and horse thief.

And that’s the fun thing about history, Dorothy said.

“You just get to go down all these rabbit holes,” she said. “And it’s been really fun interviewing and talking to the family members, because that’s part of the grant, too, is to reach out to the descendants, the grandkids, and say, ‘OK, what did they tell you about those guys?’”

Remaking The Cowboy Image

When Wister wrote “The Virginian,” it was a dramatic departure from how cowboys had always been portrayed.

“It was actually the very first Western, true Western fiction, written about Wyoming,” Dorothy said. “And it changed the way cowboys were portrayed. Before ‘The Virginian,’ they were portrayed as basically criminals. They were, you know, scum of the earth.”

But in Wister’s book, the cowboy was honorable and noble, and even a little romantic. That portrayal was an instant hit, inspiring many imitations from authors hoping to replicate Wister’s success.

Westerns and cowboys would never be the same again.

Wister hadn’t come to Wyoming, though, to write a book at all. He was here first and foremost as a prescription for his health.

“He really had had a mental breakdown,” Dorothy said. “He didn’t want to be a banker. He was an artist, but his dad was making him be a banker and a lawyer. So instead of going on Prozac, he came to Wyoming.”

Wister was among the Cowboy State’s first tourists. He was part of a wave of rich, young men who had time and money to spare. They could afford to just wander the wildness for six, eight weeks at a time, going wherever their hearts desired.

“He just fell in love with the area,” Dorothy said.” He wanted to come every year, but his parents got worried because they had lost some family friends. There was a story of a cook who killed one of their dear family friends, so his parents didn’t want him to come back.”

That sent Wister to Paris next, Dorothy said.

“But Wyoming is where he wanted to be, and where he was happiest,” she said. “Family obligations brought him back east and kept him there.

About That Smile

Among the many fun and interesting stories Dorothy has uncovered is one that seems to point to the first sheriff in the Bighorn Basin, Virgil Rice, as being the inspiration behind one of the book’s most famous lines, “When you call me that, smile.”

The line is part of a scene where the Virginian is playing a card game. He’s thinking about whether to bet when Trampas pops off with, “Your bet, you son-of-a …“

In the story, the Virginian whips out his pistol, holding it unaimed on the table.

With a space between each drawling, softly uttered word, the Virginian issues the line as something of a command. It is a telling moment in the book.

“Or, it could have been another guy,” Dorothy said, a little impishly, suggesting there is more than one story to come about that smile.

Dorothy will also have telling details on Wister’s two guides among the three or four Wister episodes she has planned for this year’s Outlaw podcast series, which begins next week.

And she isn’t ruling out more episodes as more history comes to light. But she does promise to keep the series engaging and fun for all ages.

“We’re going to keep it PG because I really want it to be used in schools,” Dorothy added. “Our local school has been using it to teach kids. The fifth through eighth grades have been having their kids actually listen to it and do assignments off of it, because it offers them local, Wyoming history that they can’t get anywhere else.”

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.