Yellowstone National Park was busy in 2023. After the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic and the historic floods of 2022, more than 4 million people visited America’s first national park this past year.

Underneath all those visitors, the ancient and turbulent geology of Yellowstone was percolating away, as it has for millions of years. And while there was more human traffic on the parks surface last year, what was happening below was fairly uneventful.

But uneventful is relative, because even at its most calm, scientists monitor thousands of earthquakes in what they call them “swarms.”

Mike Poland, geophysicist and scientist in charge of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, told Cowboy State Daily that geologically, Yellowstone “had overall sort of a quieter year.”

Poland published a geological retrospective of 2023 in the Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles, a weekly blog of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. After reviewing a year of earthquakes, geyser eruptions and the burning heart of the supervolcano itself, the conclusion is that there weren’t any earth-shattering events in the ever-changing Yellowstone Caldera.

And any year that the supervolcano doesn’t explode and destroy humanity is a bonus.

All Shook Up

The earth is always moving in Yellowstone, and there was plenty of movement in 2023, Poland said.

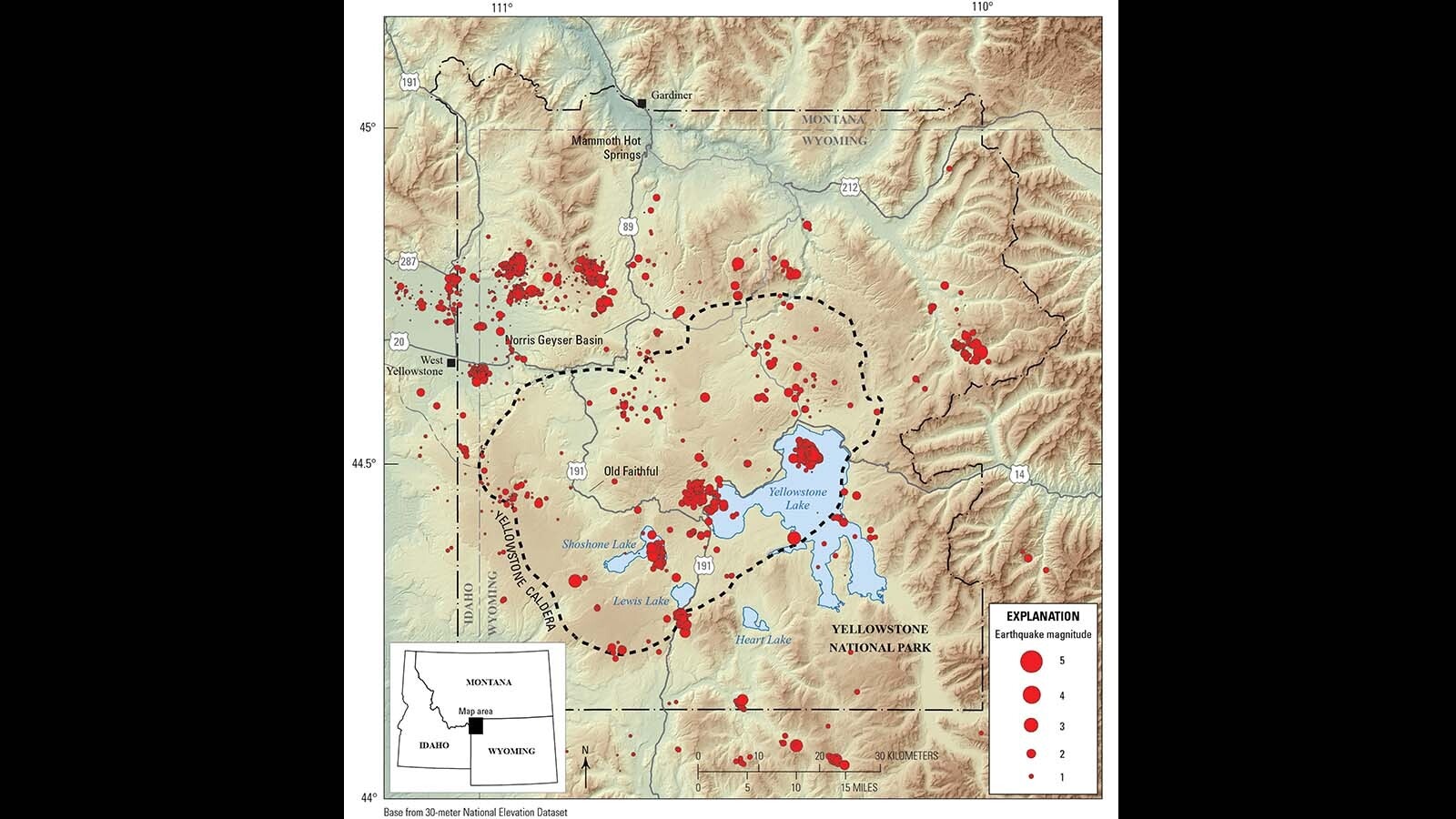

Yellowstone experiences an average of 1,500 to 2,000 earthquakes a year, and while there was plenty of seismic activity in 2023, he said it was noticeably less than average.

“It was on the low end of what we typically see in terms of the range of seismicity,” Poland said. “This past year, we had about 1,600 earthquakes. So, we're at the low end of the range.”

Seismicity varies year-to-year for reasons only known to Yellowstone. There were nearly 3,500 earthquakes detected in 2017, but only around 1,200 quakes in 2019.

Contrary to public belief, earthquakes are rarely generated from the Yellowstone Caldera (aka the supervolcano). Most happen in swarms along the numerous minor fault lines running throughout the park.

The largest earthquake of the year, a 3.7-magnitude event, was detected March 29, 2023. Ninety-nine percent of the 2023 1,600 earthquakes were magnitude 2.0 or lower, well below the threshold where park visitors could feel them.

Geyser Or Geezer?

On Dec. 30, 2023, Steamboat Geyser in the Norris Geyser Basin had its final water eruption of the year. The world’s largest active geyser erupted nine times in 2023, which tells Poland that its current period of activity could be concluding.

“Steamboat has continued to calm down,” he said. “It had 48 eruptions each in 2019 and 2020. This past year, it only had nine, so Steamboat may be gradually going back to sleep.”

Steamboat Geyser is known for its cycle of active and inactive periods. The most recent cycle started in 2017 with 10 eruptions, but the frequency has declined since 2021.

But while the one giant geyser calmed down, the giant geyser surprised everyone by firing up. The Nov. 23 eruption of Giant Geyser in the Upper Geyser Basin near Old Faithful was the most exciting eruption of the year.

The 250-foot-high Giant Geyser last erupted in 2019. The 2023 eruption could indicate the geyser is entering its own active period.

Poland also said there was an episode of “thermal unrest” in the Upper Geyser Basin over the summer.

“At Geyser Hill, near Old Faithful, some new features formed, and some dormant features came to life in late May. They threw some hot water and debris onto the boardwalk, so a short section was closed,” he said.

The “thermal unrest” in May had mostly settled by the end of June, he said. By August, the activity had ceased and the boardwalk reopened.

It’s nothing to get too excited about. Poland said such events aren’t usual, especially around Geyser Hill, citing a similar incident that happened in the same area in 2018.

“It's not a sign of the ground heating up or anything like that,” he said. “It's just that the plumbing systems are fragile and always changing. The geyser basins in Yellowstone are incredibly dynamic, so you shouldn't expect them to be the same from year to year.”

Sinking To New Depths (Sorta)

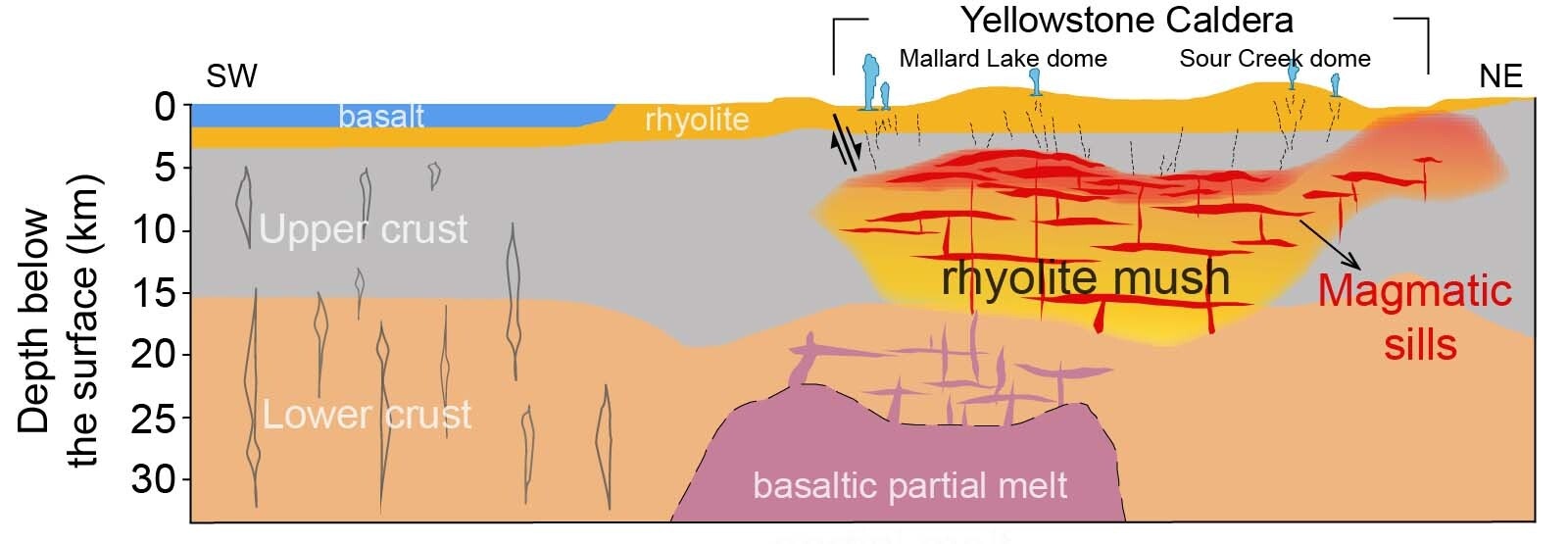

Most people worry about Yellowstone National Park going up in an apocalyptic explosion of ash and magma that would turn Wyoming, Montana and Idaho into a giant crater and ending humanity. In reality, the park has been going downhill for the last several years.

The Yellowstone caldera is subsiding, getting roughly an inch lower every year. In 2023, Poland said the subsiding trend continued as expected.

“The overall trend is this gradual subsidence of about an inch a year,” he said. “Sometimes it'll turn around. There had been uplift from 2004 to 2009 and 2014 to 2015. The ground goes up and down, but it's been going down since 2015.”

Poland said the subsidence happens slowly throughout the year with a pause in the summer. As water from the summer runoff flows into the park, the ground absorbs the water and expands “like a sponge,” as Poland described it. This halts the subsidence until the summer heat dries out the ground, and it continues its gradual descent.

The idea of the volcano’s caldera subsiding could be a little unsettling. However, Poland said the continuous subsidence is a sign that nothing of concern is happening underground.

“The ground subsiding is telling us that there's no active intrusions or anything like that. We’re not seeing things that are necessarily related to any caldera activity,” he said.

Listening Under The Boiling Teapot

The most significant developments of 2023 were made by the scientists of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory and others who monitor and attempt to understand Yellowstone's ever-changing ways. Poland was most excited about the new monitoring station installed in the Norris Geyser Basin.

“When we install GPS stations and seismometers, we avoid the geyser basins because those are really noisy,” he said. “There's hot water running all over the place, which makes a lot of seismic noise and causes the ground to bounce up and down. If you want to track overall activity in the region, you don't want to put your seismometer next to a boiling teapot because it's kind of all the noise will come from there.”

The new Norris monitoring station has three microphones inside that will pick up the acoustic signals from geyser eruptions and track them to specific geysers in the basin.

“When Steamboat Geyser erupts, we see a powerful acoustic signal coming from Steamboat,” Poland said. “It’s very famous for having a water phase and transitioning after some minutes to a steam phase. It's sort of like a jet engine. We might learn something about that kind of transition between water and steam by looking at the acoustic signals.

“I'm rather excited to see what this will show us and whether or not it would justify trying to install more stations like that, not only in Norris but in other geyser basins in Yellowstone, to see what's going on.”

Another research project studying Steamboat Geyser determined it’s been active for much longer than previously thought.

Yellowstone’s second superintendent, Philetus Norris, who led the park from 1877-1882, claimed the geyser formed and first erupted in 1878. Wood fragments collected from the geyser’s mineral deposits determined Steamboat has been active for at least several hundred years longer than that.

Poland also shared that research completed in 2023 reveals the behavior of Yellowstone’s lava flows. He pointed out that the elevated topography visible from Old Faithful is the cooled-over remnant of lava flows that happened in the caldera after the volcano's last major eruption more than 600,000 years ago.

“These lava flows are not like what you see in Hawaii,” he said. “They’re not thin, runny, orange oozing things. These lava flows are hundreds of feet thick and come out of the ground almost solid. It’s like mountains of rubble moving across the landscape.”

After accurately dating the lava flows, Yellowstone Volcano Observatory determined the flows weren’t “evenly spaced over time.” It’s possible that multiple different lava flows were flowing from different areas of the park simultaneously.

“I'm always sort of flabbergasted when you're standing and watching this incredible display of geyser activity,” Poland said. “The density of geysers in that area of Yellowstone is more than any other in the world. But the geologic story isn't just those geysers. As you look around, you're surrounded by lava flows that happened since the last big explosion. To me, that is a fascinating part of the geologic story that usually isn't appreciated. When you're standing at Old Faithful, you're surrounded by lava flows.”

Candyland

The ever-changing nature of Yellowstone National Park is one of its alluring features. For Poland and the other scientists at the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, it’s the gift that keeps giving.

“I used to be a staff member at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory,” he said. “One of the things that I really found enticing about that place is that every day there was something new. There, you might actually have eruptions and really consequential changes. Yellowstone's interesting because it's very similar in that every day could be something new.”

The scientists at the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory can’t predict what will happen in 2024. Steamboat Geyser could go dormant or roar back to life, and a new earthquake swarm could completely change the behavior of a thermal area. Unpredictability is the only predictable factor, and that’s what makes it so dynamic.

“It's always changing,” Poland said. “And as a scientist, that's Candyland.”

Andrew Rossi can be reached at arossi@cowboystatedaily.com.