MIDWEST — The richest 80 acres in the nation can be found just north of this central Wyoming town east of Interstate 25 between Casper and Buffalo.

It’s part of the 9-mile-long by 5-mile-wide Salt Creek Oil Field that during its boom days in the 1920s drew 17,000 people to Midwest alone. Add to that the other company-owned camps around it where people lived and worked, the area rivaled the size of today’s Casper.

The field during its peak produced more light crude oil than any other field in the world, earning millions of dollars for mineral rights holders and investors. It continues to send oil down its pipelines at a rate of 8,500 barrels a day.

Salt Creek Oil Field historian and Contango Oil and Gas Co. engineer tech Everett DeWitt has spent more than 40 years working in the field. Over a nine-year period starting in 2006, his role was to find every oil well that had ever been drilled in it. Digging into old Oil and Gas Commission records and BLM files has made him the expert on this oil field.

He recently hosted Cowboy State Daily for a visit at the Salt Creek Museum on C Street in Midwest, and was quick to point to a photograph of one of the many characters that make up the field’s history.

Cy Iba And The ‘Iba 80’

“Cy Iba was the first one to make authentic claims out here,” DeWitt said.

Iba staked his claims next to oil seeps in the late 1890s. Some historical accounts say Iba, who originated from Pennsylvania, had sought gold in California and Idaho prior to settling in Wyoming.

A Dec. 1, 1898, story in the Natrona County Tribune newspaper reported that Iba “went to Cheyenne last week to have a hearing in the United States term of court, regarding some oil land in Natrona County, returned home Friday evening, the case being put off until the next term of court.”

To make a claim, one had to dig a hole 6 feet square and 10 feet deep with a mineral in it, DeWitt said.

“He would dig a hole next to an active seep and, of course, he would have an oil claim,” he said. “The main ‘seep’ that he claimed was called Jackass Springs, and it is just northwest of town here. Jackass Springs was a spring of oil.”

Historical accounts say $100 worth of improvements had to be done to maintain the claim.

The Sept. 12, 1901, edition of the Natrona County Tribune reports that, “Cy Iba left last Saturday morning for the Salt creek oil country, where he intends to fix up the roads and do some other assessment work on his land.”

DeWitt said that in addition to other claims, Iba laid claim to 80 acres of land with title and deed, which has become known as the “Iba 80.”

“More money has been made off of that 80 acres than any other 80 acres in the United States,” DeWitt said.

Legal Fights

Iba died in 1907 before he saw any great wealth from the claims because of legal wrangling after the Dutch Company hit a discovery well in the field in 1908. That well triggered a flood of oil seekers and companies to the region.

The potential for wealth led to claim jumping, legal fights and literal fights — sometimes armed.

A newspaper account from 1909 relates that Mary G. Iba, “executrix of the estate of Cy Iba,” was allowed to put a monument on her husband’s grave and could not spend more than $350. Other legal notices show her as a defendant in court property disputes with oil companies.

“The U.S. government withdrew this field from homesteading for a period of time and there were legal battles continuously,” DeWitt said.

The nation’s Homestead Act of 1862 allowed for homesteaders at least 21 years old to file for 160 acres of federal land. After five years, if the filer improved the land, he could claim ownership.

Eventually, claims were ironed out. Mary Iba had been able to hold onto the 80 acres, and when she died July 12, 1951, at the age of 99, she left an estate worth $500,000.

An article in the Dec. 9, 1951, Casper Tribune-Herald attributed her wealth to the “Iba eighty in the Salt Creek field” and stated that “in 1911, when the oil royalties began pouring in, Mrs. Iba built her home at 604 South David, and she and her family resided there.”

One well, called Iba Six, initially came in at several thousand barrels a day, DeWitt said. When the well died back, operators would shoot it with nitroglycerin and it would ramp up back up. He said it is still producing 100 barrels a day.

The Roaring ’20s

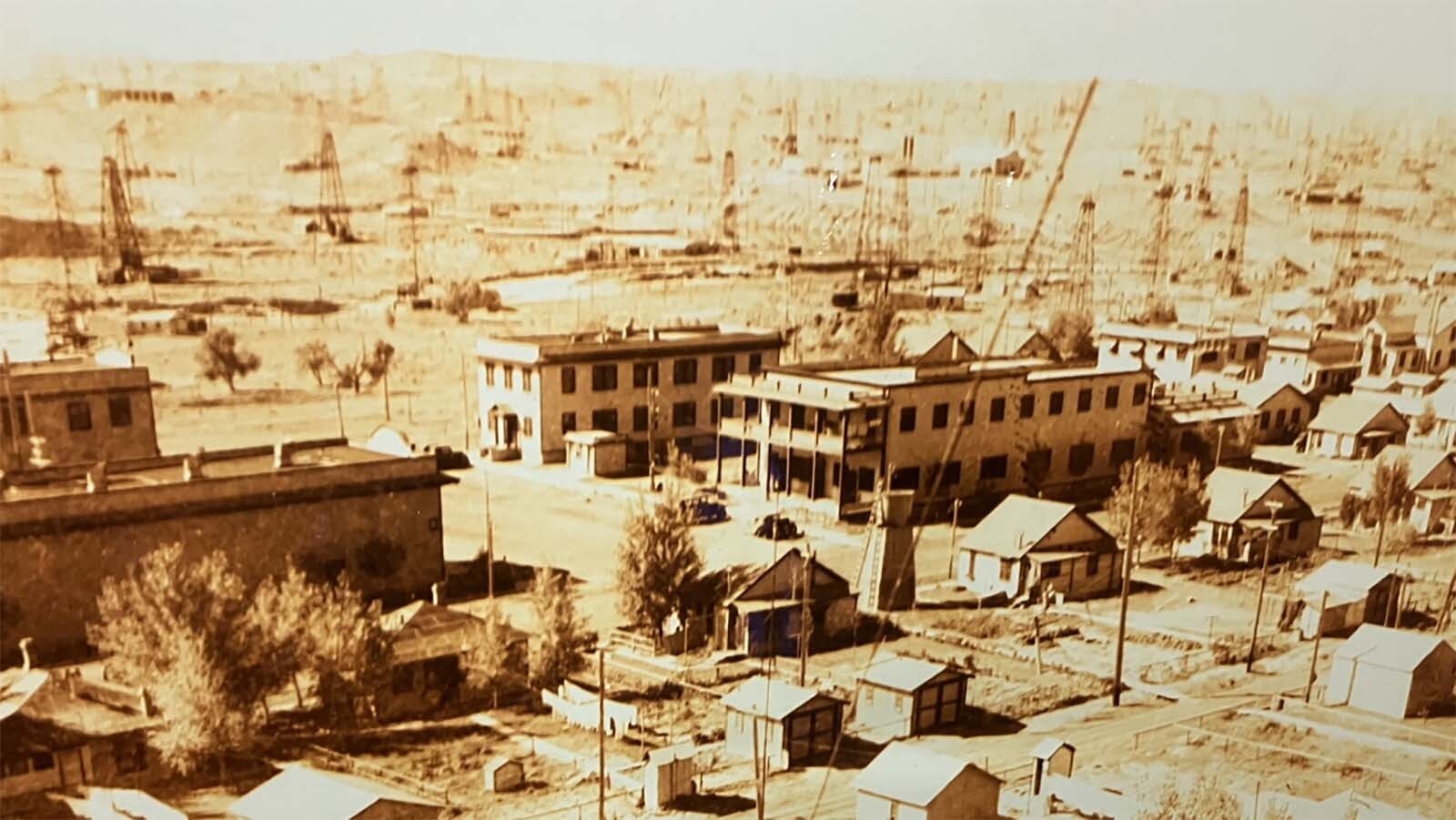

DeWitt said that during its heyday in the 1920s, the Salt Creek Field had more than 50 operators with leases on acreage, some with 160-acre quarter sections or entire sections of the field. Each operator created his own camp where employees would live and work. Photos of the camps at the museum show derricks sprinkled between rows of homes.

In addition to Midwest Oil Co., which was formed by Colorado Springs man Verner C. Reed around 1909, there were Sinclair camps, Continental Camp, Consolidated Camp, Staley Syndicate the Scotch Camp, and more.

In Midwest, as in other camps, operators tried to lure married men with families to work the fields, which at the time were little more than derricks and desert. Houses in Midwest were built at a clip of five a day and the company poured money into giving families something to do.

“Those producing companies knew that a married man with a family was more stable than a young buck who would come in and work three days and get a paycheck and go drink it,” DeWitt said.

When the North South Railroad arrived in 1923, it helped transform the community by bringing building materials in and shipping oil out. It also helped transform Midwest into a place that became livable for wives and children.

There was a hospital, schools, electric plant, theaters, commissary, shops, bowling alley, shooting range and seven golf courses in the area, DeWitt said.

“Anything that you could get in New York or San Francisco, even down to fresh seafood, you could get in Midwest then,” he said.

DeWitt said by 1925, there were 1,980 wells sending oil to Casper down the first welded pipeline in the world. The pipeline was completed in 1922.

Dangerous Work

Working in the oil field brought its dangers.

Light oil is extremely flammable, and during his research, DeWitt has found original accident reports related to oil rig fires and explosions. One particularly deadly one happened in 1927 when the men had tried the nitroglycerin technique to stimulate production of the well.

“The hill where this well sits right now is called Dead Man’s Hill,” DeWitt said. “They shot it with nitro and they were trying to get a control valve on it. Well, something happened and it exploded. It caught fire shooting more than 100 feet into the air. Three men died immediately and two more died getting off the location. About a week later, another guy succumbed … (and) there were several others who were injured pretty bad.”

In 1932 as field operations matured, DeWitt said Midwest Oil Co. consolidated the field through agreements and buyouts. The field would be run by a single operator from then until today.

As the Great Depression arrived, the Salt Creek Field experienced a fall in demand and financial issues, just like the rest of the country. The railroad stopped running in 1935. DeWitt said oil was pumped, but if things broke there was no money to fix the equipment.

World War II changed everything and brought new life as the nation needed oil to fuel its war efforts.

In the 1960s there was another boom brought by the use of water-injection into the field to get wells flowing again. DeWitt said when he arrived in 1980, it was difficult to find housing. By the late 1990s, Wyoming’s familiar boom-bust cycle had busted again.

New Technique

When Anadarko Petroleum bought the field in the early 2000s for $265 million, a boom returned as it changed the field from water injection to CO2-injected fracking wells. When the company arrived, the field was producing about 3,500 barrels a day. The CO2 technique took it up to 15,000.

Two years ago, Contango Oil and Gas Co. bought the history Wyoming oil field and about 80 employees continue to keep its 2,000 producing wells operating.

DeWitt said the field continues the CO2 injection using a five-die pattern where the middle well is the injector and there are four corner producers. He said his research discovering the nearly 5,000 wells that have been drilled in the field during its history continues to pay off.

“The interesting thing about that is some of these wells that were drilled in 1918 and plugged in 1934, we have been able to go back in and make those a well again if they fit our five-spot pattern,” he said. “We can go back in and reactivate those wells, and that costs us about $400,000 whereas drilling a new well would be about $1.5 million.”

The Midwest that was the company town became incorporated in 1978. DeWitt said he didn’t like the place he moved to in 1980, but he has come to enjoy living in a community that boasts such a rich past.

“In Midwest, we’re stable. Some of the people who live here work in the field, and some in Casper,” he said. “I love it here. I am one hour away from anything I want to do. Prior to moving here, I was an over-the-road trucker and I thought, ‘Who would want to live in a place like this?’ Now you couldn’t drive me out with a big old stick.”

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.