An archaeological excavation of Evanston’s historic Chinatown, a community that was built in 1868 and burned in 1922, has so far turned up more than 300,000 artifacts, and confirmed insight into an early Wyoming holiday tradition.

Nobody ate fruit cake back then, either.

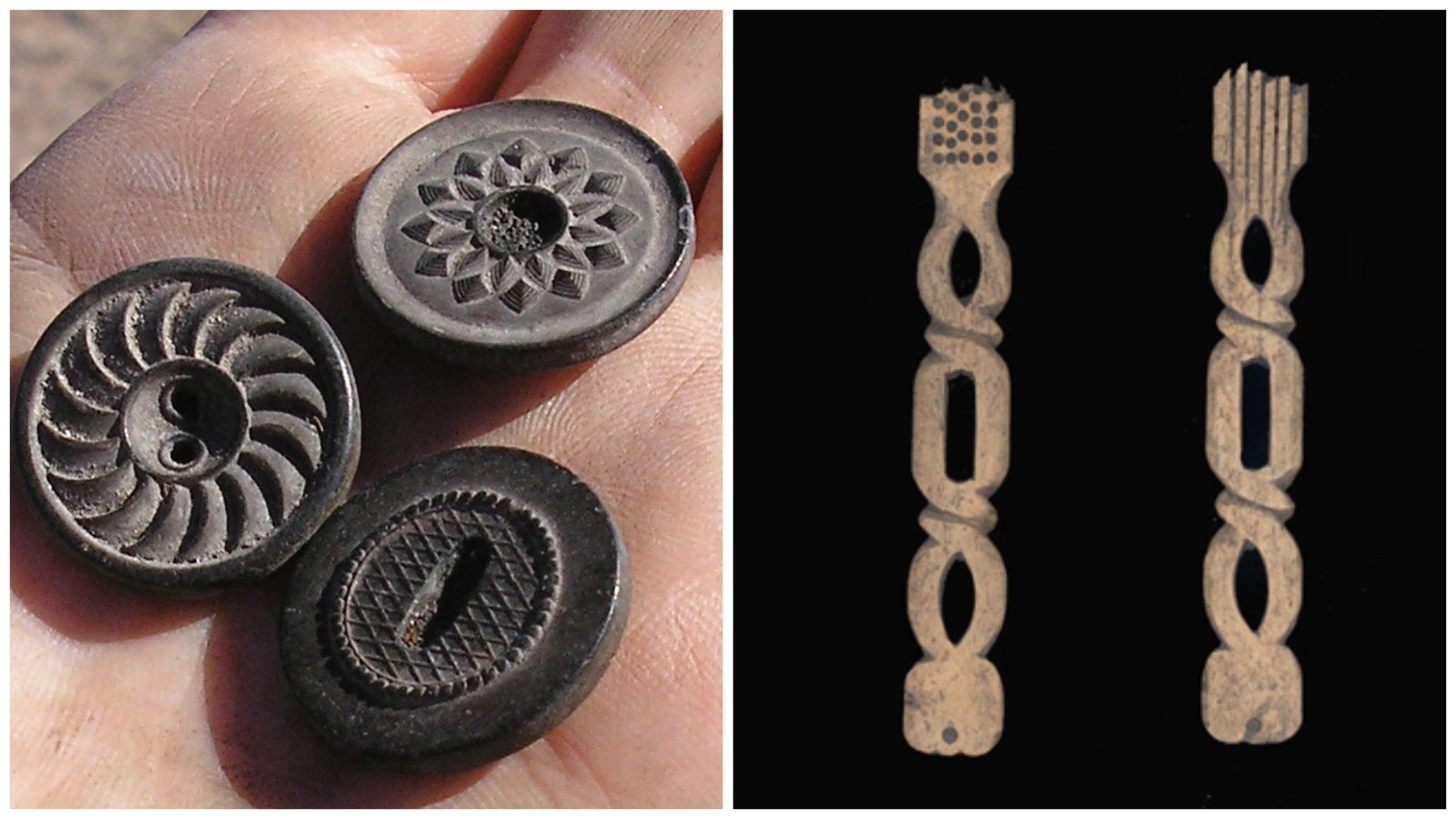

The dig started in 1994 and over 30 years, researchers have found a wide range of cultural artifacts, including toothbrushes and chopsticks carved from bone, coins, jewelry, brandy and champagne bottles, opium tins, herb vials and the bones of cattle, pigs and fish caught in the Pacific Ocean.

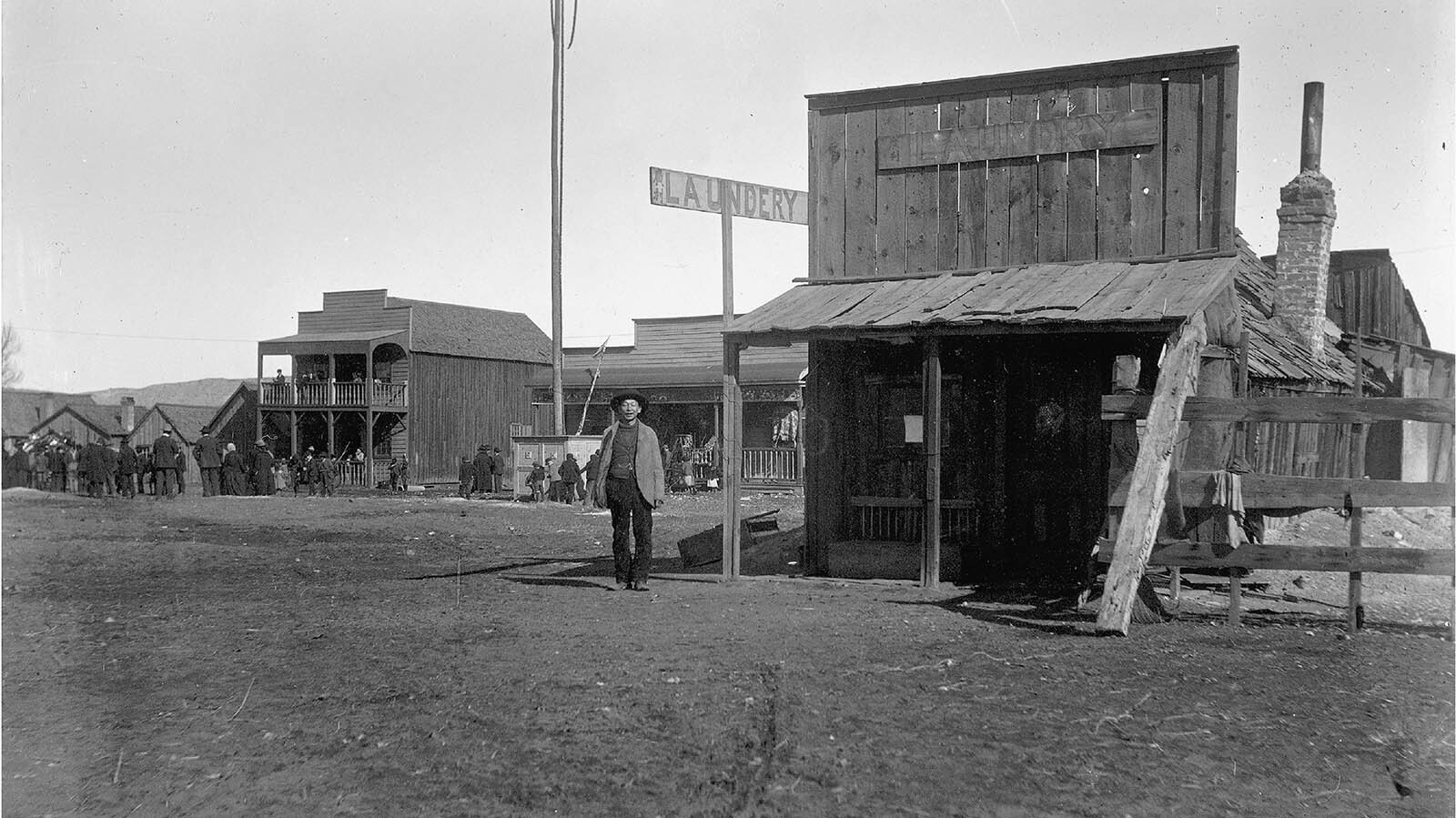

Evanston’s Chinatown was built west of the original townsite on a beach along the Bear River. It was surrounded by the river on three sides and is where researchers from the Wyoming State Parks Department and other partners conducted the excavation.

Ceramic dishes, pots and teacups, pickled vegetables, lettuce, radish, rose hips, imported figs and grapes, strawberries, raspberries and part of one very old fruit cake were found.

An isotopic investigation of the pig bones revealed that the pigs were corn-fed.

A wallet and a set of keys are believed to have been tossed in an outhouse.

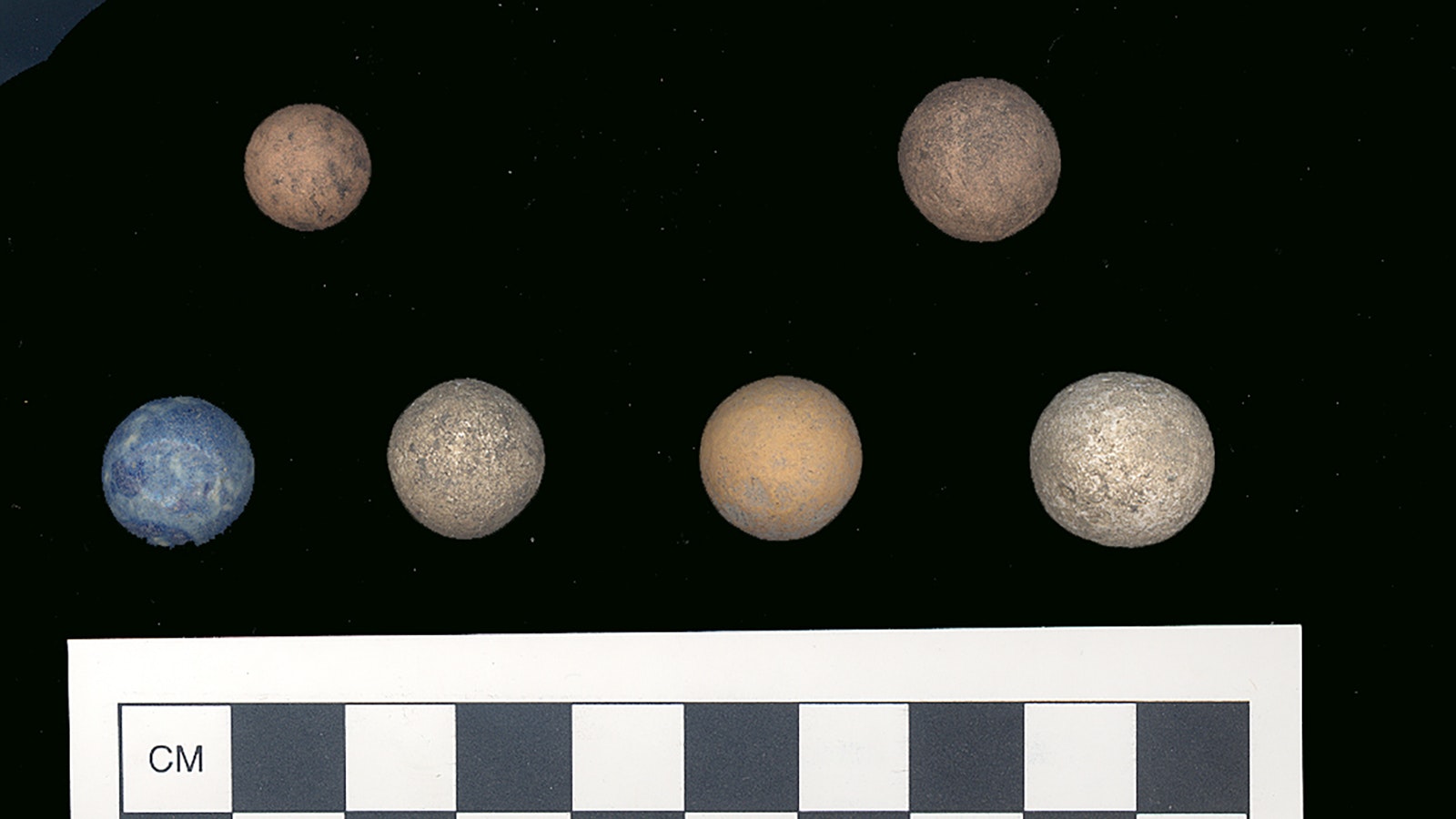

They also found dice, dominoes and other gaming pieces carved from bone. Historical records show gambling was common. Research for the project revealed that Evanston may have had the only Chinese brothels in Wyoming.

Dr. Dudley Gardner, an archaeologist and historian with Wyoming State Parks, said the excavation to date includes a house and a laundry/general store. He said the buildings were abandoned and nearly everything was left in place after Union Pacific Railroad set fire to Evanston’s Chinatown in 1922 to get rid of ownership records and clear the tax files.

Chinese History In Southwest Wyoming

The railroad also is part of what brought Chinese workers to southwest Wyoming in 1868 at about the same time as Wyoming became a territory. They were recruited to work in coal mines and to fix parts of the recently completed Transcontinental Railroad that runs east to west across southern Wyoming.

The Transcontinental Railroad was built between 1863 and 1869 by Union Pacific, which started laying track at Omaha, Nebraska, and Central Pacific Railroad Co. of California that started its work at Sacramento, California. The two companies raced toward each other, meeting at Promontory Point in northern Utah on May 10, 1869.

Gardner said corners were cut in the race to lay track across Wyoming and Utah, and several sections had to be fixed in the years that followed because the rail bed had washed out or was inadequate. Chinese workers were brought in to complete that work.

They were predominantly young men who were stationed along the rail line in section camps, and near coal mines. They also established segregated communities in Rock Springs and near the Bear River in Evanston.

The Chinese workers were willing to work for lower wages and were not members of the prominent unions. This caused labor strife and several Chinese workers were killed in Rock Springs in 1885 and at Idaho’s Hell’s Canyon in 1887.

Anti-Chinese sentiments led to the U.S. government adopting the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. That law put a stop to Chinese immigration for 10 years and was the first and only major U.S. law that prevented all members of a specific national group from immigrating to the United States.

Burn It Down

The Chinese Exclusion Act was extended by 10 years in 1892 and by 1922, there were only three Chinese still living in Evanston, Gardner said. After the buildings were burned, some of the area was covered in road base and paved.

Evanston’s Chinatown had several buildings and businesses including a Joss House, or Chinese temple, blacksmith shop, two laundries, a general store and several private residences.

A Joss House museum of Chinese immigrants who lived and worked in Uinta County from the 1870s through the 1930s features a scale model of Evanston’s Chinatown, artifacts and historic photographs.

Gardner said the structure that was excavated was well-preserved because of the asphalt and road base cap that covered it for many years. The building was used as a laundry, butcher shop, and general store that sold a wide variety of items.

“It was a real stroke of luck from an archaeological perspective,” he said. “They had abandoned everything you can imagine in that basement. It was clear they were entrepreneurs and would sell whatever was needed.”

An Enterprising Community

Gardner’s dissertation, titled “Two Paths One Destiny: A Comparison of Chinese Households And Communities in Alberta, British Columbia, Montana and Wyoming, 1848-1910,” shares that Evanston Chinese entrepreneurs were involved in diverse range of businesses.

“Restaurants, laundries, and vegetable stands marked the small town,” Gardner wrote. “Signposts in Evanston advertised, in Chinese, that cooked chicken and oysters were available. The smell of fish and oysters mingled with the sounds of fresh vegetables being cut on chopping blocks. Elsewhere in town, other shops appeared.”

A Chinese entrepreneur named Chung Kee was the first to integrate Evanston’s business district.

An ad placed in the Uinta Chieftain on March 28, 1885, states: "City Laundry II, Chung Kee, Dealer in Chinese and Japanese Goods and Oriental Curiosities, New House near Railway Depot, Evanston Wyoming."

Gardner’s research on the time period is full of accounts about the people who lived in Evanston and the surrounding area, and about the demographics of the population.

And A Lonely One

Evanston was one of the more demographically diverse communities he studied. There were 15 females who lived there in 1880, a much higher percentage than in the other Chinese communities of the Intermountain West where women made up 1% to 3% of the population.

Many of the Chinese laborers left wives in China and didn’t return home for decades. Gardner points out that loneliness was a common plight among the men.

“Consider, however, the difficulties that Chinese men faced in finding a mate,” the dissertation states. “For single men living in a society that did not accept interracial marriages, and where, in 1860, Chinese men outnumbered Chinese women 1,858 to 100, the odds bordered the impossible.”

According to the U.S. Census of the Wyoming Territory in 1880, there were 348 Chinese men living in Rock Springs and only one Chinese woman.

The same census shows there were 192 Chinese men and no Chinese women in the coal mine town of Almy, located about seven miles north of Evanston. An explosion at that mine killed 35 Chinese miners in 1881.

What They Ate

A lot of the archaeological evidence found in Evanston provides a record of what was eaten at the time. They found fish bones that were local — probably from the Bear River — and other fish that came from saltwater, including sea bass, California perch, cuttlefish and shark.

Excavations at two of the section camps along the rail line found evidence that they ate skunk, badger and mule deer.

“We found that they were eating those animals in two Chinatowns that we excavated in Uinta County,” Gardner said. “The Anglo-Saxon people there were eating them too, not just the Chinese.”

Recorded Evidence

Records show Chinese immigrants paid poll taxes in Uinta County in 1868. Gardner said the tax was a prerequisite to vote and cost $1 per person, or about one day’s wages. It was one of the only ways a territorial government could levy a tax at the time.

“The Chinese paid those taxes and it provided a solid record of Chinese in Uinta County,” he said.

U.S. Census data shows that by 1885 there were close to 1,500 Chinese living in Uinta and Sweetwater counties combined. Gardner said there were 200 to 400 Chinese who lived in Uinta County at that time.

They lived communally. An average of 10 people lived in each home, and many lived in dugouts cut into banks or tents.

Most came from southern China’s Guangdong Province, Gardner said. They were recruited by Ah Say, who became the superintendent of the Chinese Union Pacific workers. Prior to his death in 1899, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States and was appointed as consul by the Emperor of China.

Gardner said Ah Say was a key figure in recruiting workers to Wyoming at the time because he came from Guangdong Province and could speak Toisanese, a different language than either Cantonese or Mandarin, the predominant languages spoken in China.

Nearly half (42%) of the people killed in the Chinese massacre in Rock Springs in 1885 were from Guangdong Province, Gardner said.

Ah Say owned property in Evanston and signed a contract in 1874 to bring in Chinese mine workers.

Celebrations

Newspaper stories from the time period include dozens of accounts of the colorful celebration of Chinese New Year, which begins on the new moon that appears between Jan. 21 and Feb. 20.

As part of the celebration, it’s tradition for families to clean their homes to sweep away any ill fortune and make way for incoming good luck. Public celebrations include the dragon dance, fireworks and giving money in red envelopes.

Gardner said it’s also traditional in Chinese culture to venerate the dead.

“They would prepare a feast and the smell of the food would be enough appease the ancestors,” he said.

An Ongoing Research Project

The researchers and historians working on the Evanston Chinatown project have collected so much data that Gardner said he probably won’t live to see the end of the research.

Most of the artifacts are stored in Evanston. Gardner has started hauling some of them to Grinnell College, in Grinnell Iowa, where students there are working to catalogue the items. A partnership developed with Stanford University and its celebration of the 150th anniversary of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 2019. The Sweetwater County Historical Museum and two museums in Uinta County are also involved in the project.

Gardner saw China for the first time from the deck of an aircraft carrier during the Vietnam War. He’s been intrigued with the country since.

“Most people come here to mine the minerals or build a resume and then they leave,” he said. “I really admire the people who stay. The Chinese had grit, and even though they had limited resources they did the best they could with what they had.”

John Thompson can be reached at: John@CowboyStateDaily.com