Amelia Earhart was looking to disappear long before she flew away from the world 86 years ago. But before that, the world’s most renowned female aviator fell in love with the Wyoming after her first visit in 1934.

When Earhart soared off the radar July 2, 1937, over the Pacific Ocean, her new home was being built in remote northwestern Wyoming. Work stopped the next day after it was learned Earhart was lost.

Earhart Defied Convention

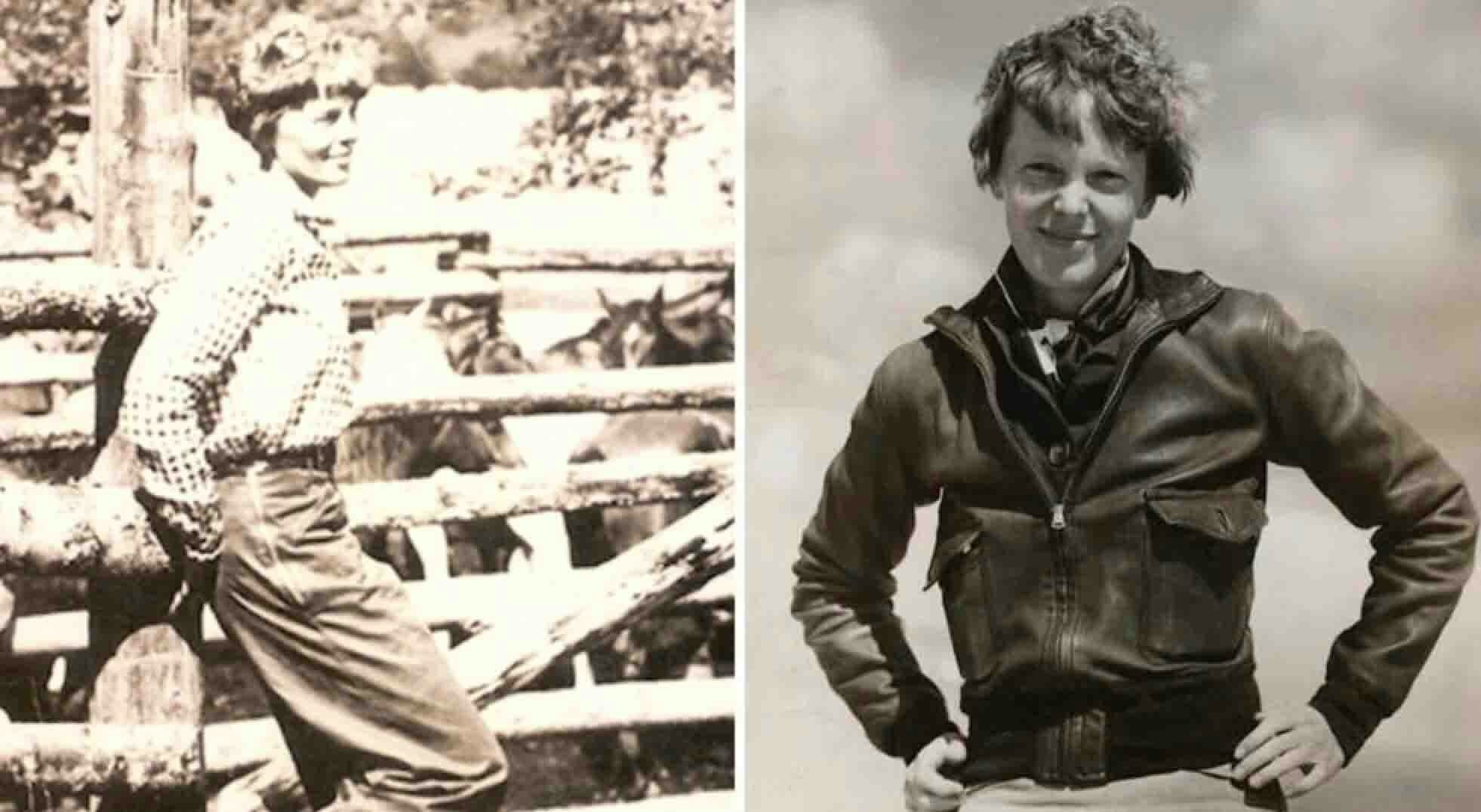

Earhart was cut out to be a Wyoming girl from the beginning. A bit of a tomboy, “Meely,” as she was called, grew up climbing trees, hunting rats with a rifle and pulling off daredevil stunts with her little sister Grace (“Pidge”) as her audience.

Brought up to break female conventions of the time, Earhart once built a roller coaster ramp on the roof of the backyard shed with the help of her uncle and launched herself off it in a makeshift wooden box. The crash resulted in a bruised lip, a torn dress and a kindled appreciation for flight.

“Oh Pidge, it’s just like flying,” she reportedly told her younger sister.

Earhart’s true interest in flying probably began in 1917 when she was a nurse for the Red Cross in Toronto and heard stories from pilots returning from World War I.

In December 1920 after plunking down $10 for a 10-minute flight with ace pilot Frank Hawks, Earhart, at the age of 23, was hooked.

"By the time I had got two or three hundred feet off the ground, I knew I had to fly,” she said.

AE And GP

Earhart’s rise to fame began as George Putnam’s marriage to Dorothy was disintegrating.

A professional relationship between Putnam (known to his close friends by his initials GP) and Earhart (also known to friends as AE) began in 1928. After publishing the hugely successful autobiography “We” for aviating legend Charles Lindbergh, Putnam did the same type of marketing for Earhart.

With funding from Amy Phipps Guest, Putnam helped publicize Earhart’s historic trans-Atlantic flight, and later assisted with a book (“20 Hrs., 40 Min”) chronicling the event. The pairing helped launch Earhart firmly into the limelight.

Putnam would eventually divorce Dorothy in 1929 after her highly publicized affair with a younger man.

AE and GP eventually drifted into a relationship that became romantic and public shortly afterward. The couple married in 1931 after Earhart reportedly turned down six different wedding proposals from Putnam. “Lady Lindy” wanted to make it perfectly clear to her new husband that she would wear the pants in the relationship.

“I want you to understand I shall not hold you to any medieval code of faithfulness to me nor shall I consider myself bound to you similarly. I may have to keep some place where I can go to be by myself, now and then, for I cannot guarantee to endure at all times the confinement of even an attractive cage,” she wrote in a letter hand-delivered to Putnam on their wedding day.

Would that someplace “to be by myself end” up being Wyoming?

Need To Get Away

Putnam knew his wife had been pulled in myriad directions by an adoring public. In addition to her flying exploits, Earhart launched her own clothing line in 1933 with the assistance of renowned fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli.

Putnam figured his wife could use a little detox in the tranquility of the mountains in Wyoming. The famed publisher had visited Yellowstone in 1921 with his first wife Dorothy. His guide was outfitter and packer Carl Dunrud. The two kept in touch.

Earhart herself had first been in Wyoming in 1931 while flying her gyroplane (precursor to the helicopter) across the country, stopping at Cheyenne, Laramie, Parco (present-day Sinclair), Rock Springs and Le Roy for frequent refueling.

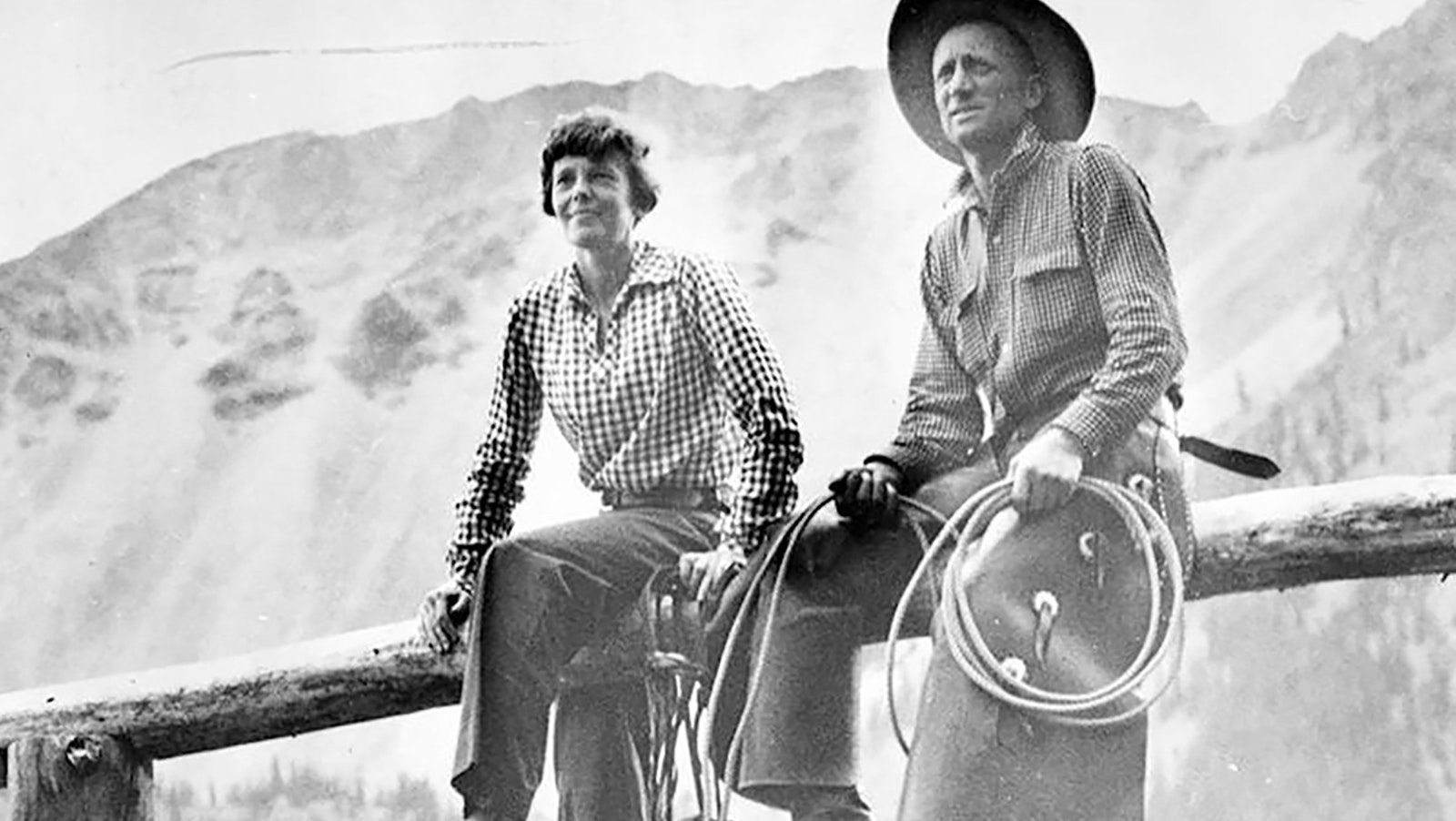

So Putnam contacted Dunrud. Dunrud invited the couple to his newly constructed Double Dee Guest Ranch high up the Wood River valley 32 miles from the nearest town — tiny Meeteetse.

Dunrud had bought huge swaths of land, including the entire ghost town of Kirwin, a high-elevation mining town that crapped out in 1907 after a fatal avalanche scared off the few remaining hangers-on. Gold and silver had been discovered there in 1885 and the rush brought a population of 200 with some 38 buildings at its height.

Earhart Drives To Wyoming

Earhart arrived first. She drove her Franklin cross-country from Rye, New York, to Wyoming.

Incidentally, 1934 was the final year of production for the legendary Franklin Automobile Co. out of Syracuse, New York. The air-cooled luxury car made the climb to 9,200 feet above sea level and parked at the ranch.

When Putnam arrived, the couple was treated to a two-week pack trip high into the Absaroka Range around the peaks of Mount Sniffel and Brown, Chief and Dundee mountains.

Earhart was hooked.

She enjoyed the quiet nights with no sounds, but the gurgle of a nearby stream. She filed claim on a mine property further up the valley a mile beyond Kirwin. She chose the most remote place she could find — so isolated it’s still today only accessible by horse or a good four-wheel drive, and only for a few months during the summer.

Earhart asked Dunrud to begin work immediately on her cabin. It was never meant to be ostentatious. Just a quaint two-room getaway in the mountains.

Dunrud had four walls and a doorframe finished, just a few logs high, when he read the headlines like the rest of the America: “Amelia Earhart Lost in Pacific — Radio Flashes Faint SOS.”

Putnam instructed Dunrud to quit building the following day.

Earhart’s possessions, which she had shipped to Meeteetse, were eventually donated by to the Buffalo Bill Museum in Cody. Also at the museum is a buffalo robe coat and flight jacket given to Dunrud by Earhart during their short friendship.

Barely anything remains of the Earhart cabin these days, but it is still visible, decaying in the tall grass. Find it from Meeteetse on 290/200 Wood River Road. Driving southwest, clock 33.7 miles to Kirwin. A good four-wheel drive is recommended. From the parking area at Kirwin, Earhart’s cabin is another mile up on the left.

Earhart Disappears Over The Pacific

Earhart’s fateful attempt to fly around the globe with one crew member, Fred Noonan, ended sometime around July 2-3, 1937. She completed most of 22,000 miles and had just 7,000 to go.

An interesting side note: A Rock Springs teenager claimed to have heard a distress signal from Earhart around 8 a.m. on Sunday, July 4. According to a story published in the Rocket Miner on July 5, 1937, 16-year-old Dana Randolph was listening on his shortwave radio when he said he heard a female voice say, “This is Amelia Earhart. Ship is on a reef south of the equator, station KH9QQ.”

There are conflicting reports on whether the tip was followed up or not after the federal government was notified. The United States spent $4 million in the search for Amelia Earhart and scoured over 250,000 square miles of ocean.

The search was called off July 19. Earhart was legally declared dead in 1939.

In the decades since, even as recent as a month ago many theories with purported evidence have surfaced as to what may have happened to Earhart and Noonan.

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.