The remains of a Union Civil War veteran have rested in a Campbell County cemetery for the past 107 years misidentified under a Confederate headstone.

The circumstances that resulted in Union Private George Henry Eighmy (pronounced Amy) being buried under a Confederate headstone are as of yet unknown.

Although researchers from Campbell County’s Rockpile Museum didn’t uncover anything mysterious related to why Eighmy was buried under a Confederate marker, they did discover a pile of information about a man with a checkered past.

And they worked with the U.S. Veterans Affairs Department in Washington, D.C., to procure a new headstone for a Union soldier that was recently placed at his grave in Mount Pisgah Cemetery in Gillette, Wyoming.

Museum educator Penny Schroder told Cowboy State Daily the research was part of an ongoing effort to recognize local veterans.

“We are doing this because every veteran deserves to be remembered and honored, and that’s what we’re trying to do,” Schroder said.

According to research conducted by Schroder and museum volunteer Greg Bennick, Eighmy died in 1916 after being married seven times. It’s likely he fought for the Union in the bloody 1862 Battle of Antietam in Maryland. He was later convicted of murder in Kansas, and grand larceny in Colorado, and he served prison time in both states.

U.S. Land Office records from 1914 show Eighmy claimed a homestead in Campbell County near Spotted Horse — current population 2 — and later died there of a heart attack.

Mismarked Headstone

When Schroder and Bennick discovered the Confederate headstone, they contacted Veterans Affairs and were told they had to prove their discovery to apply for a new headstone. They were able to find evidence that proved Eighmy served with the 35th Regiment of the New York (foot) Volunteers during the Civil War.

A muster roll shows that Eighmy was 20 years old when he enrolled May 7, 1861. He agreed to serve two years, and the roll shows he mustered out with the company in June 1863. According to the application completed by the Rockpile Museum, the highest rank he attained was private. He received no commendations related to his service and was not a prisoner of war.

After the grave marker application was filled out and approved, Veteran’s Affairs shipped a new upright granite headstone. It was recently placed at the cemetery in Gillette, Schroder said.

Among the 10 volunteers listed on the same muster sheet as Eighmy, one died at the battle of Antietam, the deadliest one-day battle in American military history; two deserted; one was transferred to another unit; and one was discharged for a disability.

The Battle of Antietam happened Sept. 17, 1862, in Washington County, Maryland. According to historical records, 22,717 men died that day. The Union suffered 12,401 deaths while the Confederate Army lost 10,316.

Schroder said while there is no direct evidence to support Eighmy was part of that battle, it is “highly likely” he was there.

Multiple Marriages

According to his obituary published in the Gillette News on April 21, 1916, Eighmy was 76 when he died of a heart attack. The obituary states he went to lie down after a “hearty” meal, “but shortly afterward his wife was attracted to strangling sounds issuing from the vicinity of the couch.” He died “before any relief could be given.”

The wife referred to in the obituary was Mary Ann Carnahan Eighmy, his seventh wife, who was 77 years old when they married. A newspaper report from the Butte Daily Post on Oct. 26, 1914, states they “were both in the twilight of life and lonely for companionship.”

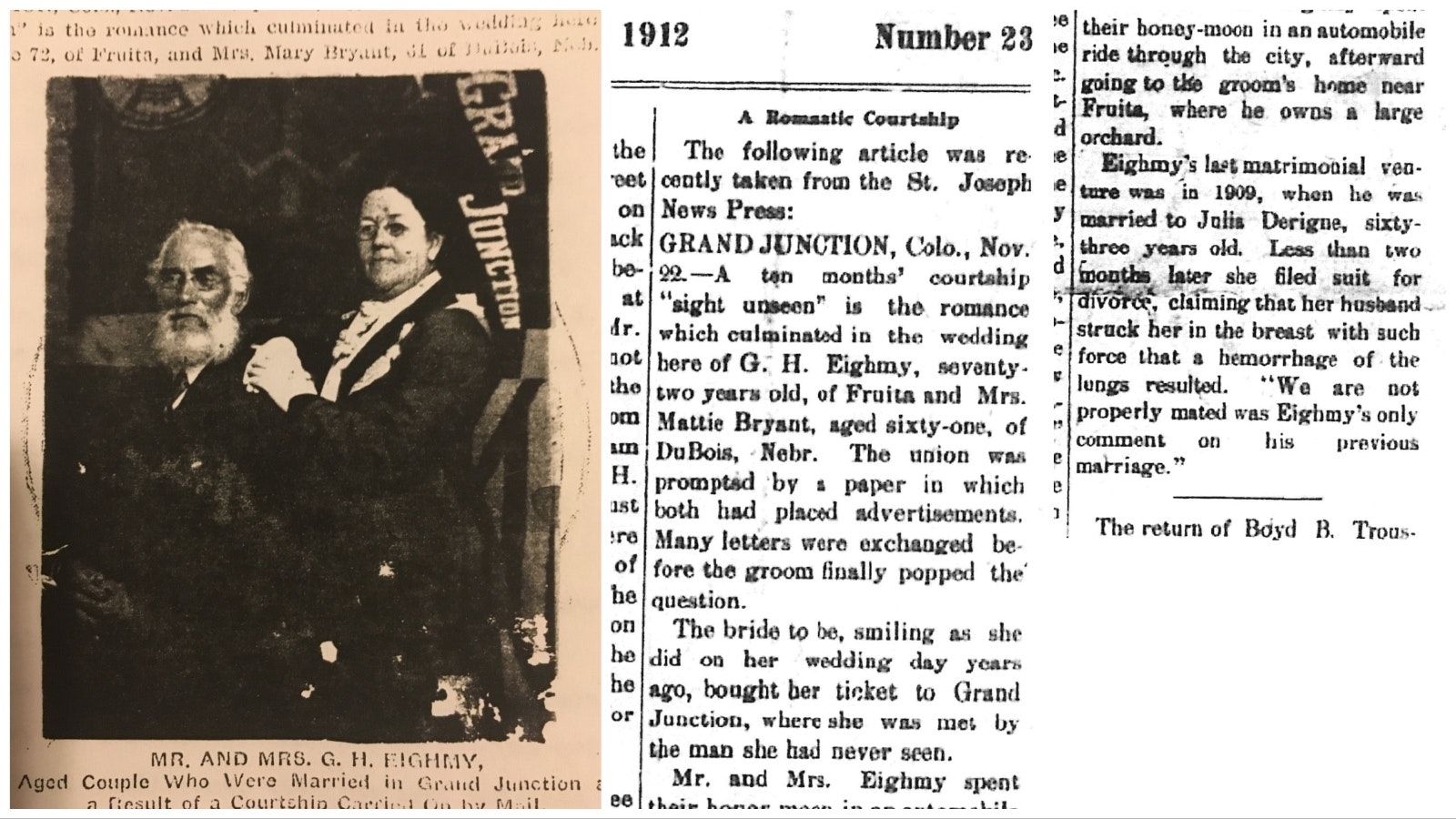

A newspaper account of his marriage to Mattie Bryant of Dubois, Nebraska, in 1912 states the couple was married in Grand Junction, Colorado, after a 10-month courtship that involved letter writing only. They were married on the same day they saw each other for the first time, according to the report.

That same report states that a 1909 marriage to Julia Derigne ended after only two months after she claimed Eighmy struck her in the chest resulting in a hemorrhage of the lungs.

Was George Eighmy An Outlaw?

A newspaper report published in The Champion (Norton, Kansas) on April 14, 1887, states that Eighmy and cohort Hugh Collins were convicted for the murder of Robert Orr. According to testimony from Eighmy and Collins, Eighmy shot Orr with a shotgun while Orr was in the process of stealing a horse.

However, Kansas state prosecutors prevailed in arguing that it was a crime of passion committed when Orr came to the farm to see Collins' wife, identified only as “Lottie.”

Many newspapers of this time period, including The Champion, were more like rambling narratives of the events of the period. There were no photographs, headlines were small and print point sizes were tiny to cram as much information as possible onto a page. They look more like oatmeal spilled on a page than modern newspapers and included multiple paragraphs of trivial information.

The Champion’s account of this particular day includes that a wealthy widower was recently elected mayor of Topeka and that “two-thirds of the lady vote was cast for him.”

That females were allowed to vote was a hot topic of the time. A second entry states voter registration at Leavenworth, Kansas, recently reached 7,000, of which 2,673 were women and “617 of these are colored.”

Another entry states: “One of the facts developed in the prohibition campaign in Michigan was, that three good, steady drinkers will support a saloon.”

However, by far the most column inches in the paper that day were dedicated to the Eighmy-Collins murder trial.

The report states that Orr rode up to the farm three separate times on a dun pony looking around for something. On the third trip, Orr entered a barn and led a filly on a halter out to where his pony was tied to a hitching post. As he mounted the dun pony, Eighmy shot him out of the saddle with a shotgun from 31 feet away.

According to the report, “The killing was done while the defendants were lying in wait. They could have apprehended Orr without killing him. To the minds of hundreds of people, the conditions and absolute facts in this killing are yet unearthed. The mystery of the killing of Robert Orr is as dark and obscure today as at first, yet two men on their own voluntary statements are to hang for the crime.”

Why Eighmy didn’t hang for the crime, as the article suggests, is unclear. Schroder found records of him serving prison time in Kansas, but no documents related to sentencing for the crime were located.

Regarding the grand larceny conviction in Colorado, Schroder said she could not find further details outside of the charge and Eighmy’s prison record there.

Research on numerous Campbell County veterans is ongoing, Schroder said, and a tour of veterans’ grave sites is being planned.