It was Aug. 21, 1841. Wyoming was not yet a state, nor even a U.S. territory. The days of the legendary mountain men were in decline as Manifest Destiny took hold and more people moved West.

But one of their number was about to make a new legend.

A young trapper named Jim Baker, freshly returned to his beloved mountain west from his home state of Illinois, had just downed a couple of buffalo cows with a fellow trapper history has recorded only as Vandusor.

As the two were butchering their animals, a cloud of dust suddenly rose on the southwest side of Bastion Mountain, which is northeast of Savery, Wyoming. That cloud of dust covered the advance of a large party of what Baker would later say were 700 angry Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho Warriors.

Not long after the cloud of dust appeared, arrows rained down on Baker and Vandusor from a cliff above.

The race for their lives was on.

The two men took off upriver toward a trading post that associate Henry Fraeb was trying to build near the mouth of what is today known as Battle Creek, located along the present-day border of Wyoming and Colorado.

Baker had, in fact, been sent by his employer Jim Bridger to warn Fraeb of increased American Indian hostilities, and to beg him to return to Bridger’s camp on the Henry Fork near Green River. There he would be safer, and more secure.

Now that doomed post was Baker and Vandusor’s only hope of survival.

They made it, just in time. But Fraeb wasn’t so lucky. He was among the first to be killed in the assault.

Baker, who was just 22, took charge of the fight from that moment on.

A Miniature Old West Version Of Thermopylae

According to Baker’s account decades later, he faced insurmountable, Battle of Thermopylae-like odds. There were perhaps two dozen trappers with him and a handful of Shoshone trappers, surrounded by hundreds of fighters from other Indian tribes.

The men believed they had no chance of survival. They could only make their deaths as costly as possible.

“We made breastworks of dead horses and hid behind stumps,” Baker told a Denver newspaper decades later.

The rifle pits they had dug still remained, Baker added, and could still be seen by those traveling in that area.

“They forted up in the corral,” one Howard Stansbury would write in his own account of the event, told to him by Bridger, who was guiding him at the time.

With limited quantities of ammunition and gun powder, Baker knew every shot had to count. Rather than fire the typical volleys, Baker instead had the men choose a particular target each time their foes tried to charge.

Each time their men fell, the American Indians would think better of their charge. They would pull their wounded and dead to safety, retreating.

“Being at such close quarters and aiming at one particular Indian, the savage selected generally fell in his tracks,” according to an early newspaper account of the fight. “Then man No. 2 would shoot, while No. 1 would retire and reload.”

That kept half of the guns loaded at any one time. Baker believed that was ultimately the key that helped prevent an open charge, which would have overrun their small fortress of dead horses stacked against the corral.

But, as the day wore on, Baker and his men were running out of powder and ammunition. Their foes, who were exhausted as well, didn’t know this, however. That night, they took their dead and wounded from the area, leaving the trappers alone.

The next morning the trappers could hardly believe the pitched battle was over. It was a stunning reversal of fate for men who had been so certain they were going to die.

The men broke camp and left the area as quickly as possible, fearing their foes could return at any moment with reinforcements.

The men later credited Baker’s leadership with saving them from certain death against overwhelming odds.

Kit Carson, who heard the story later from American Indian points of view, was told that the warriors involved in the fight believed a supernatural force had been involved in turning the battle against them. They could not otherwise understand how a battle where they’d had such overwhelming advantages had somehow turned against them.

Bastion Mountain was soon renamed Battle Mountain as a result of theremarkable fight.

But the legend of Jim Baker had only just begun to be written.

Meet Me In St. Louis

Baker was a tall and lanky lad, well over 6 foot in height, with flaming red hair. That got him noticed, and not just by ladies. In fact, it was Baker’s red hair and his height that first attracted Jim Bridger’s attention. Bridger was in St. Louis at the time recruiting trappers and scouts for John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company.

Baker was running away from home.

Baker had been sent by his parents, Phoebe and William Baker, Scots-Irish farmers in Illinois, to apprentice with a shoemaker. But Baker wasn’t interested in that at all.

Talking Baker into joining Bridger for a great expedition West, where he would learn more about hunting, scouting, and trapping, wasn’t difficult at all. Baker had grown up hunting and he loved the outdoors. What Bridger described to him was a thrilling adventure, one where he would get paid, and paid handsomely.

“Beaver were worth $5 or $6 apiece, and half a dozen beaver made a good day’s catch,” Bridger would later tell the Denver News in 1895.

That meant Baker could make an excellent living as an independent trapper, and so, a trapper he remained, well past the last mountain man Rendezvous in 1840.

In fact, Baker’s last big hunting trip was with Kit Carson and Jim Bridger in the fall of 1852. The three traveled through New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming before hanging up their mountain man caps in favor of other, more lucrative options.

Red-Headed Shoshone

Baker’s many skills included learning the languages of American Indian tribes in the region. Baker took things a step further though, actually living among the Shoshone for a time, learning their customs and even adopting their religion. Eventually he earned himself a Shoshone name that translated roughly to the Red-headed Shoshone.

It was during that timeframe that Baker would save Marina, the 16-year-old daughter of Chief Washakie, after she had been abducted by a hostile tribe.

Marina gave him a bear claw necklace for his bravery, and the two were eventually married.

She wouldn’t be Baker’s last American Indian wife, though. Baker would marry at least three American Indian women during his lifetime, and perhaps as many six, though the historical record is not clear. He would have many children as a result of these unions, some of whose descendants are still living in Little Snake River Valley communities like Dixon, Baggs, and Savery, to this day.

Those descendants are just one of many examples where Baker’s footsteps have become entangled with the Wyoming landscape in ways both subtle and obvious.

The mountain peak that overlooks Baker’s Savery home, for example, is named Baker’s Peak. Obvious enough.

But less obvious is the fact that some of Baker’s favorite trails, drawn out on his trapper maps, have since become paved highways.

Why Isn’t He More Famous?

Among his other notable achievements, Baker was General John Charle’s Fremont’s guide on a third expedition to explore and map the American West, a party that also included Kit Carson.

And he was part of the Bartleson-Bidwell Party, which was the first wagon train to travel overland on the Oregon Trail.

He was also one of Denver’s first settlers, where a stained-glass likeness of him has been placed in the Colorado capitol building, highlighting him as among a dozen who shaped that particular state.

Despite all of his considerable achievements, however, Baker’s story is less well-known to the world outside of Wyoming than that of contemporary mountain men such as Kit Carson, Jim Bridger, and Hugh Glass. All of them have been portrayed in various films set in the time period.

Perhaps one reason that Baker is less well-known outside of Wyoming is that he shunned publicity. He didn’t want to spit tobacco juice into a spittoon because it was too pretty, and, battle-scarred though he might be, he didn’t care to be world-famous either.

Not that he didn’t have the opportunity. Ned Buntline tried to interview him for a biography, but Baker refused. He knew that Buntline had already made men famous, but Baker didn’t care if the world forgot who he was.

In fact, when Denver became too populated for his taste, he picked up and moved to less populated Savery, Wyoming, building a new homestead there, and living in it in relative obscurity, until he died in 1898.

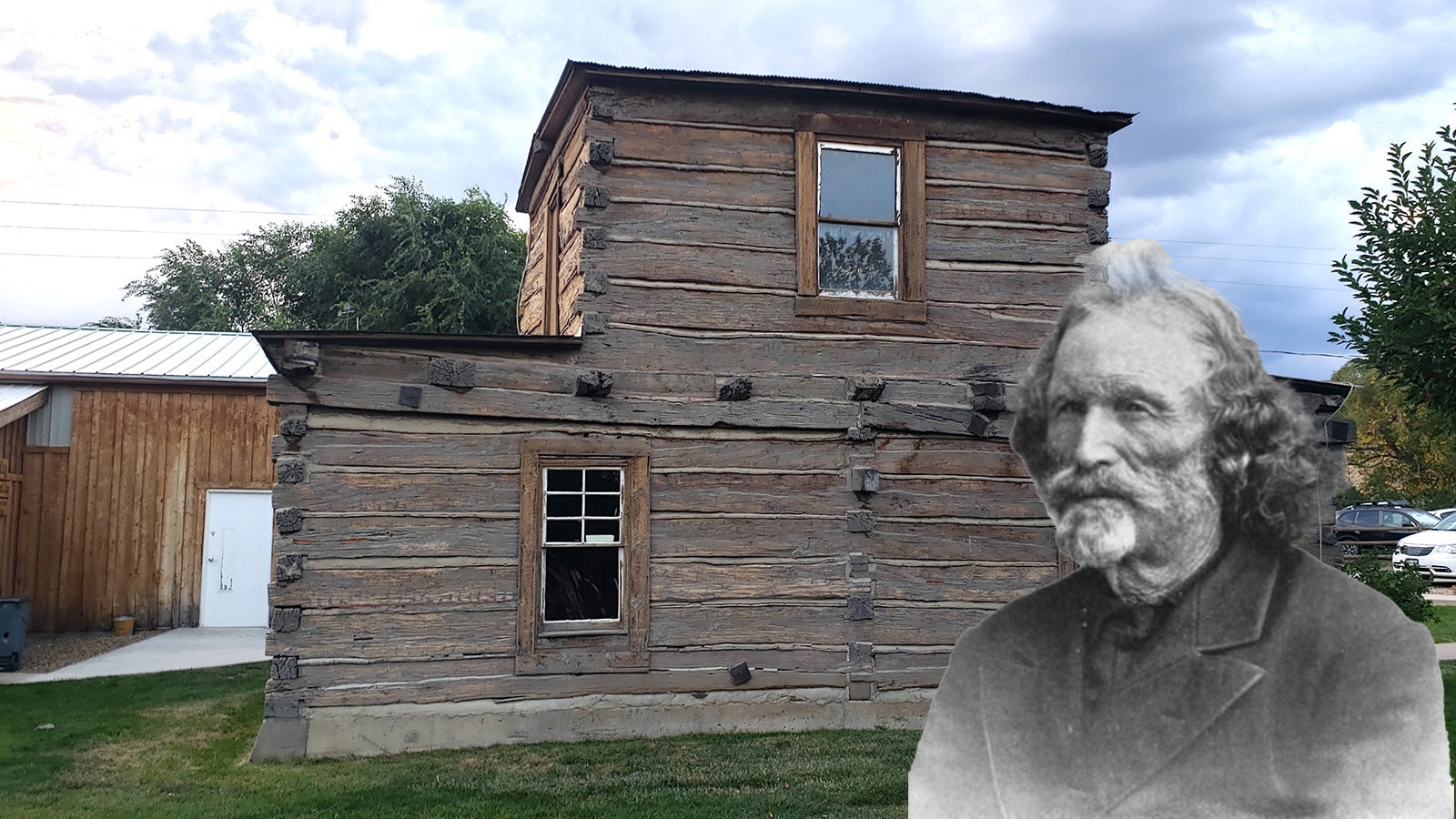

It is telling, however, that of all the places Baker roamed, it was Savery, Wyoming where he chose to finally plant his own little castle cabin on the plains, a two-story building that looked like a miniature fort.

In fact, it was a small fort. Historical documents say it included a third story to serve as a watchtower, because Baker had been convinced that certain American Indians who didn’t like him were likely to come to call at his relatively isolated homestead.

If they showed up, Baker was prepared to make them pay dearly for the visit.

The third-story turret was taken down about four years after the cabin was built, as tensions with American Indians eased.

The log cabin Baker built from the hand-hewn logs that he and some of his children felled remains to this day in Savery, at the Little Snake River Museum. There was a tug-of-war, for a time, between Wyoming and Colorado over who would keep the cabin, which Wyoming ultimately won.

That the home still stands today, much as it was 150 years ago, is just another way that Baker has quietly held down the fort far longer than most ever could.

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.