Hardly a day has gone by this summer season where a tourist in Yellowstone National Park hasn’t been caught doing something illegal, dangerous, stupid — or all three.

Facebook page Yellowstone National Park: Invasion of The Idiots! has become the TMZ of the NPS (National Park Service). Public shaming hasn’t seemed to slow offenders much. Healthy fines do not appear to be a deterrent either.

On Wednesday, three visitors were caught on video strolling off boardwalk at the Grand Prismatic thermal pool. Apparently, they missed the memo. New day, new episode of “touron” behavior that boggles the mind.

Truth be told, though, the National Park Service itself did not always practice healthy wildlife hygiene. There was a time when the West was wild, and that included the park.

Only it was a wrong kind of “wild” and a period in Yellowstone’s history that park rangers would likely sooner forget.

A Less-Than-Stellar Past

The tacit, unwritten policy in the early 1900s was to look the other way when it came to how bear encounters were handled. By today’s standards, Yellowstone officials then set a perfectly horrendous example of how not to conduct oneself with wild and unpredictable animals.

As if the lax attitude toward bear encounters wasn’t enough, things went from bad to worse beginning in 1919 when Horace Albright took over as superintendent of Yellowstone.

Today, Albright is heralded as somewhat of a conservationist. He was instrumental in defining the National Park Service and its role, serving as the second director from 1929–1933.

But in his early years after being appointed superintendent of Yellowstone, Albright was all about commercializing the park to the horror of modern-day conservationists and the ultimate ruin of any semblance of a natural encounter with nature.

Albright set out to make Yellowstone a flagship of the agency and demonstrate how a park would be managed under the new National Park Service.

To the good, he helped found important components like visitor services and park museums. On the downside, Albright also went a bit overboard is promoting the wonders of Yellowstone to the world.

Claiming NPS had a “duty to present wildlife as a spectacle,” Albright instituted a circus-like atmosphere in Yellowstone that bordered on an all-out zoo. In fact, at least two separate zoos operated inside the park at one time.

The Buffalo Jones Museum & Zoo was basically a rundown log cabin where the former bison hunter and one-time game warden once lived.

The zoo consisted of “four very tame bears, a badger, several coyotes, a pet buffalo calf and a number of different species of birds,” according to promotional materials of the age.

Yogi Bear And A Big Boo-Boo

Many are familiar with the so-called “hold-up” bears that accosted traveling motorists along the road. These were mostly pesky black bears that could be appeased with the bribe of a Twinkie or whatever tourists had on hand in the station wagon.

But that was just the beginning. Park rangers went from being complicit in setting a bad bear example to outright promoting a culture of naughty.

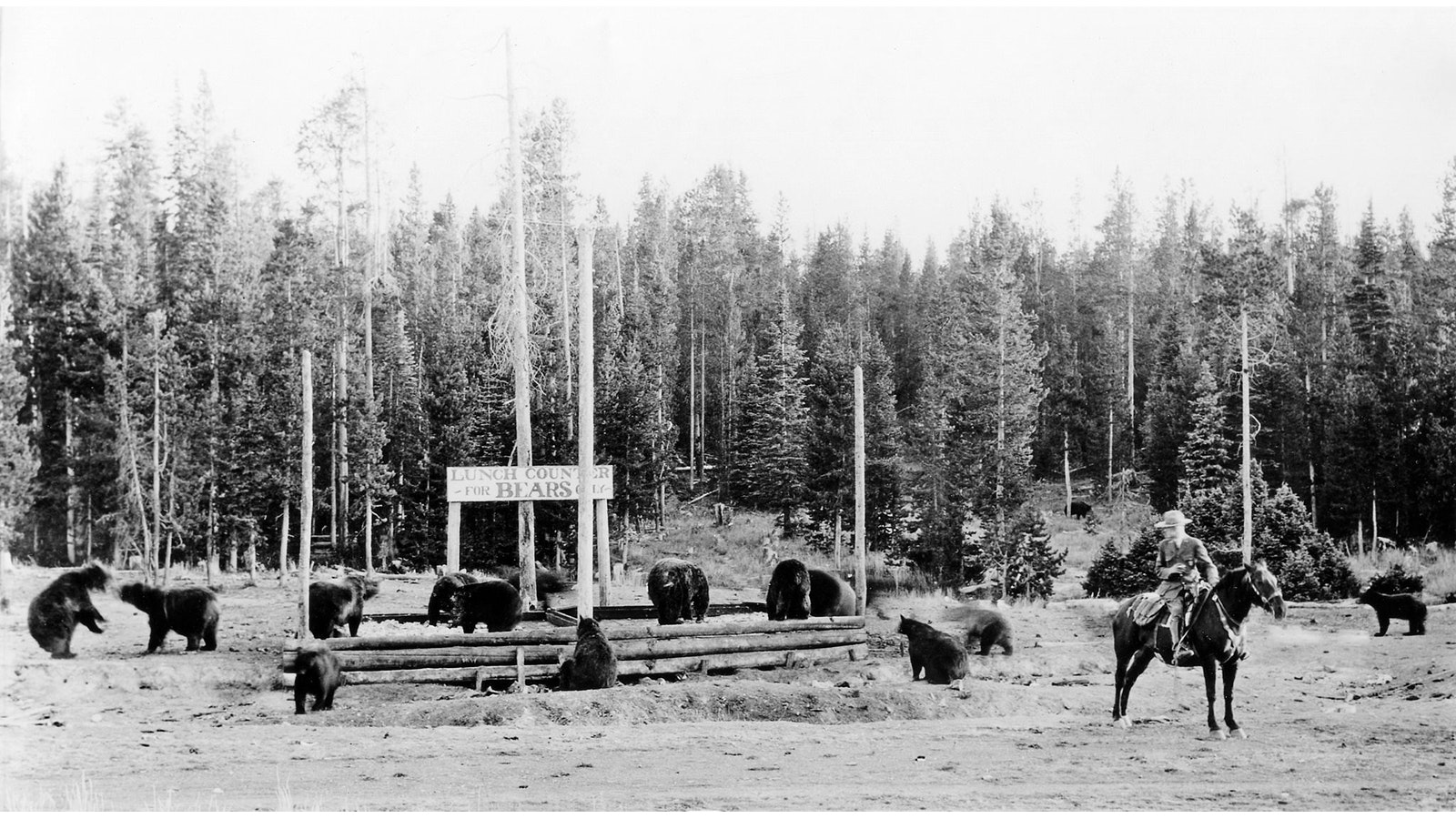

Under Albright, the “Lunch Counter for Bears” was established behind Old Faithful Inn complete with bleacher seating for hundreds. The full-on dinner show was billed in a 1920 hotel brochure as a place where one could “photograph a wild bear and eat a course dinner in the same hour.”

What was once a convenient garbage disposal for park employees where food scraps magically disappeared thanks to dozens of handy marauding bruins, became one of the park’s biggest attractions in the Roaring ’20s.

A larger bear feeding frenzy took place at Canyon Hotel as well. The spectacle sometimes drew a reported 50-70 bruins at a time, snacking on food refuse bait tossed there by park employees. No one saw anything wrong with the practice. After all, a fed bear was a happy bear; tourists were entertained and the park got rid of its garbage.

In his work “Book of a Hundred Bears,” P. Dumont Smith recalled being miffed in 1909 at the same things that visitors to Yellowstone complain about today.

“Other tourists were slow and loud,” he wrote.

He also recalled with aplomb what today would be considered a terrifying incident.

“In the night I was awakened by [a bear], twice, rubbing against my bed. It was just against the wall of the tent and in the half-light his bulk showed who it was. The second time I kicked him hard and he gave [a] protesting little whine and went away.”

Surprisingly, the bad example set by the park did not result in the human mortality rate one might expect. Scratches, bites and knockdowns were fairly regular, but only one fatality — a park employee (Frank Welch) killed by a grizzly — was recorded during the heyday of hilarity lasting about a decade. Bears called “bad actors” that did not play nice were shipped out to zoos or simply shot.

In his book “Oh, Ranger!” Albright stated, “Mr. Bear knows he can eat a lot more in an eight-hour day if he eats ‘combination salad’ at the bear pits than he can if he nibbles at tidbits stolen from campers.”

While the delicate, if not potentially litigious, arrangement worked, it was hardly a naturalist’s dream.

Bison Take Center Stage

During his tenure as Yellowstone’s boss, Albright also built a bison corral and stocked it with a dozen or so of the park’s finest buffalo.

When bison threatened to overgraze Lamar Valley, Albright arranged to have hundreds slaughtered and even petitioned for a permanent plant where the animal could be rendered onsite in Yellowstone.

In 1925, Hollywood came calling when movie producers making a Western called “The Thundering Herd” needed to film a huge stampeding bison herd for a critical scene. Two of the nation’s largest private bison breeding ranches both had fewer than 500 head. Movie producers wanted more.

Albright promised to round up all the bison he could. The park contained an estimated 2,000 buffalo at the time, but buffalo keeper Bob LaCombe and 18 of his mounted rangers could only get about 700 together after weeks of trying. It would have to do.

Years after the film’s release, Albright would regularly refer to Lama Valley as the home of “the famous Thundering Herd.”

Return To Sanity

Beginning with Albright’s departure to head the NPS in 1929, things in Yellowstone began returning to a new kind of wild.

Unsafe practices were phased out by better-informed wildlife managers, even against Albright’s will. Park biologists submitted new guidelines for the park, predicated on the idea that “every species ... be left to carry on its struggle for existence unaided.”

Lunch Counter and other bear shows were discontinued, and feeding wild animals was discouraged — although begging bears continued to be a problem in Yellowstone through the 1960s and ’70s. Consistent messaging that continues today eventually led the way to a more natural experience seen now.

A few of these long-gone examples of how not to interact with wildlife might be a good reminder for some of today’s visitors who still occasionally fail to understand how the park tries to keep wildlife truly wild.

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.