For a millennia or more, petroglyphs and pictographs on the rock canyon walls of the Wind River IndianReservation have been telling their stories to the sky and the sun, the wind and the rain.

But their day is almost done.

“With these extended droughts we’ve been having and then sudden surges of moisture, we’re seeing a lot of mass wasting,” retired cultural resources specialist Mike Bies told Cowboy State Daily. “Big chunks of the rock face are just falling off.”

Bies has had a 30-year career with the BLM as a cultural resources specialist. A large part of that career, since 1987, has been working with the petroglyphs and pictographs at Legend Rock State Petroglyph site near Thermopolis.

More recently, however, he’s been working on a volunteer basis to photograph the ancient rock art that’s present on the Wind River Indian Reservation. His goal is to get photographs of as many rock art images as possible. He’s also scanning some of the rock faces into a program that could one day recreate 3-dimensional models of the rock art that’s being lost.

But time for the project is running out quickly.

“We went back a couple of weeks ago to a place that we recorded last year, last fall, and one of the panels just fell over this winter,” he said.

The panel that recently fell weighs 600 to 700 pounds. That makes transporting it somewhere in a way that doesn’t completely destroy it all but impossible, Bies said.

Structures to protect the rock art, meanwhile, would have to be a quarter mile or more long in each area. There are so many areas to document, that this is not really feasible either.

“All we can do at this point is just document this before it gets (lost),” he told Cowboy State Daily.

That’s what he’s been working to do ever since first encountering the sites last year in July.

“It’s a project I cannot finish in my lifetime,” he said.

There are just too many of the rock art images to record.

What Is Rock Art

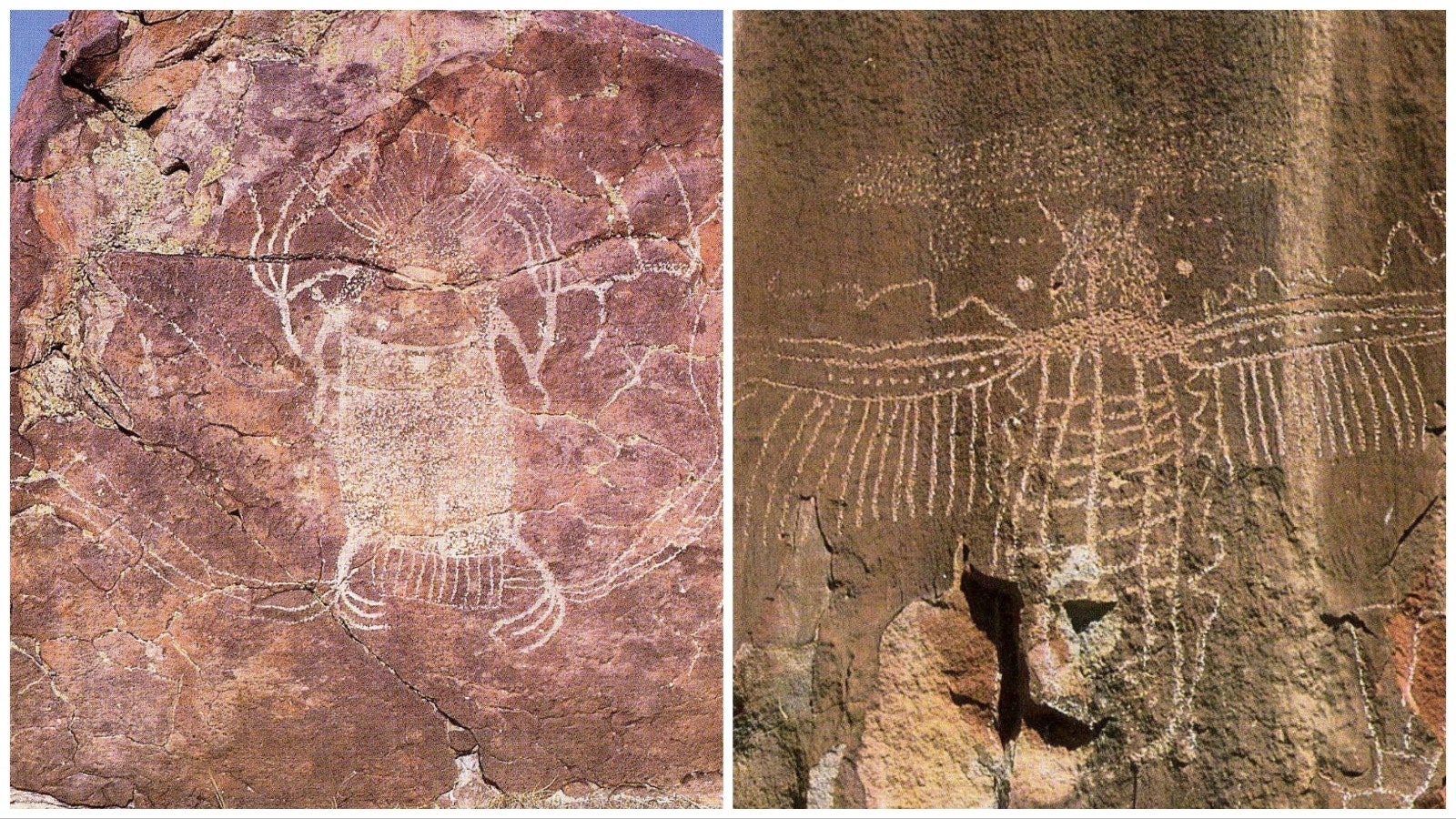

Rock art is called a petroglyph if it is carved into rock, or a pictograph if it has been painted onto rock with pigments. Usually, rock art has elements of both techniques — though wind and time may wear pigment away or erase parts of carved lines.

That’s where experience comes into play. Bies has had many years of experience looking at rock art images. He’s also studied the rocks that such images are typically carved into, so he can tell the difference between pigment and normal rock colorization.

“It’s the difference sometimes between dreams and reality,” Bies said. “You look at many, many rocks to get a sense of them. And then you can tell when it’s pigment.”

Marks that were made by nature can sometimes also become confused with intentional marks.

He takes out a magnifying glass to look at the grains of sand gliding in the sun sometimes, just to be sure he’s interpreting the image correctly.

He also takes into account the many examples of rock art he’s seen over the year. He’s very familiar with all the common shapes and forms that make up the Dinwoody tradition that’s common to the Wind River-Bighorn Basin system.

That tradition is also spread throughout the cold deserts of North America and the Rockies, Bies added.

“If you just say cold weather, that covers it,” he said.

Going Behind The Image

Scholars have their debates about what to call ancient petroglyphs and pictographs. Are they rock art, rock imagery, or something else?

Whatever they are called, the images also have a variety of subjects or purposes.

“In terms of subject matter, we’ve got bragging,” Bies said. “That’s mostly people telling stories about things they’ve done, things they want to do, or things they wish they could do.”

There’s also the whole “Killroy was here” type of thing or “Sally and Nancy had a good time with Joe.”

Then there is the supernatural rock art, depicting otherworldly entities.

“That’s actually the dominant type of rock art that we see in this part of the world,” Bies said. “Bighorn Basin is dominated by these large, mostly patterned-body anthropomorphs.”

Some of the best examples of Dinwoody rock art and pattern-body anthropomorphs are available to the public at Legend Rock, complete with interpretive materials, Bies added.

The rock art on the Wind River Indian Reservation is not open to the public.

Portraits Of Another World

The human-like figures Bies are often presented like portraits.

“Frequently, they’re in a line, you know, not just one guy or gal, whatever they are,” he said. “You’ll see three, four, or five, or more just standing there, like they’re looking out at you.”

Anthropologist Dr. Larry Loendorf, who has taught at several universities including North Dakota and New Mexico, has done a lot of work on the ethnography surrounding these otherworldly portraits in the Dinwoody style, which includes Wyoming. That work suggests the human-like figures represent deities, as well as lesser beings that, while not gods, still have supernatural powers.

“When you talk to the elders, they talk about these images being a result of this being, this deity, this entity presenting itself into this dimension,” Bies said. “There’s the rock world behind the rock face, and the reason the images are at that particular point is because the barrier, the boundary between those dimensions is weak there.”

Take Nothing, Leave Nothing Behind

Because of this belief, people going to locations with that type of rock art are advised to prepare for the encounter appropriately.

“You’d want to present the right energy,” Bies said. “You’d want to do the right things. I don’t want to call it rituals, because they really aren’t that well defined. One of the things the elders stressed, though, is that you need to be very, very much aware, if you’re in that neighborhood where those images occur, of yourself and your own mental attitude. You need to be grounded and stay focused, rather than kind of losing your way into something you might not want to get involved in.”

One should never take anything from the site or leave anything behind.

“If you do, you’re creating a link between yourself and that spot, and those entities could use that link to come where you are,” Bies said. “Not necessarily to affect you, but to affect your family. You might be strong enough to deal with them. But children or older people might not be able to do that. So there’s a real strong concern amongst most of the old guys that I dealt with over the years in knowing what they’re getting into (first).”

Not all the rock art images are necessarily deities, Bies added.

“They have little (figures) who are associated with them,” he said. “They’re quite frequently associated with these more powerful characters, trying to cater to the powerful’s whims in order to further their goals.”

These lesser entities are not necessarily good or bad. They are looking out for themselves and have their own agendas, though, which may or may not be good for others, and they, too, may have supernatural abilities.

“They’re just trying to do what they can to enhance their situation,” Bies said. “And there’s really a lot of fun stories in the ethnography that gives us a little bit of a clue about what’s going on. But it reinforces this idea that they're indeed personages, or deities — entities — of one sort or another.”

Getting Future Generations Involved

All of the information Bies is gathering on the locations and nature of rock art on the Wind River IndianReservation is being shared with the tribal archaeologist and the tribal historic preservation office so they will know what they have where.

Bies has been talking with tribal representatives about getting some students from the tribe involved in further documenting the images as well.

“My first step is to get the locations down,” he said. “And to photograph and label the panels. But one of the things I think would be really useful would be to bring out, say middle school students, to help fill in the details.”

The students could be trained to measure the rock art images, list their colors, and note other important details.

“It’s something where you’d have to have a real hands-on collaboration,” Bies said.

This year, though, has been a tough year for Bies’ documentation efforts.

“Winter started early and lasted so late,” he said.

That’s put the work far behind where he’d hoped to be by now.

“We’re where I hoped we’d be in April at this point,” he said.

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.