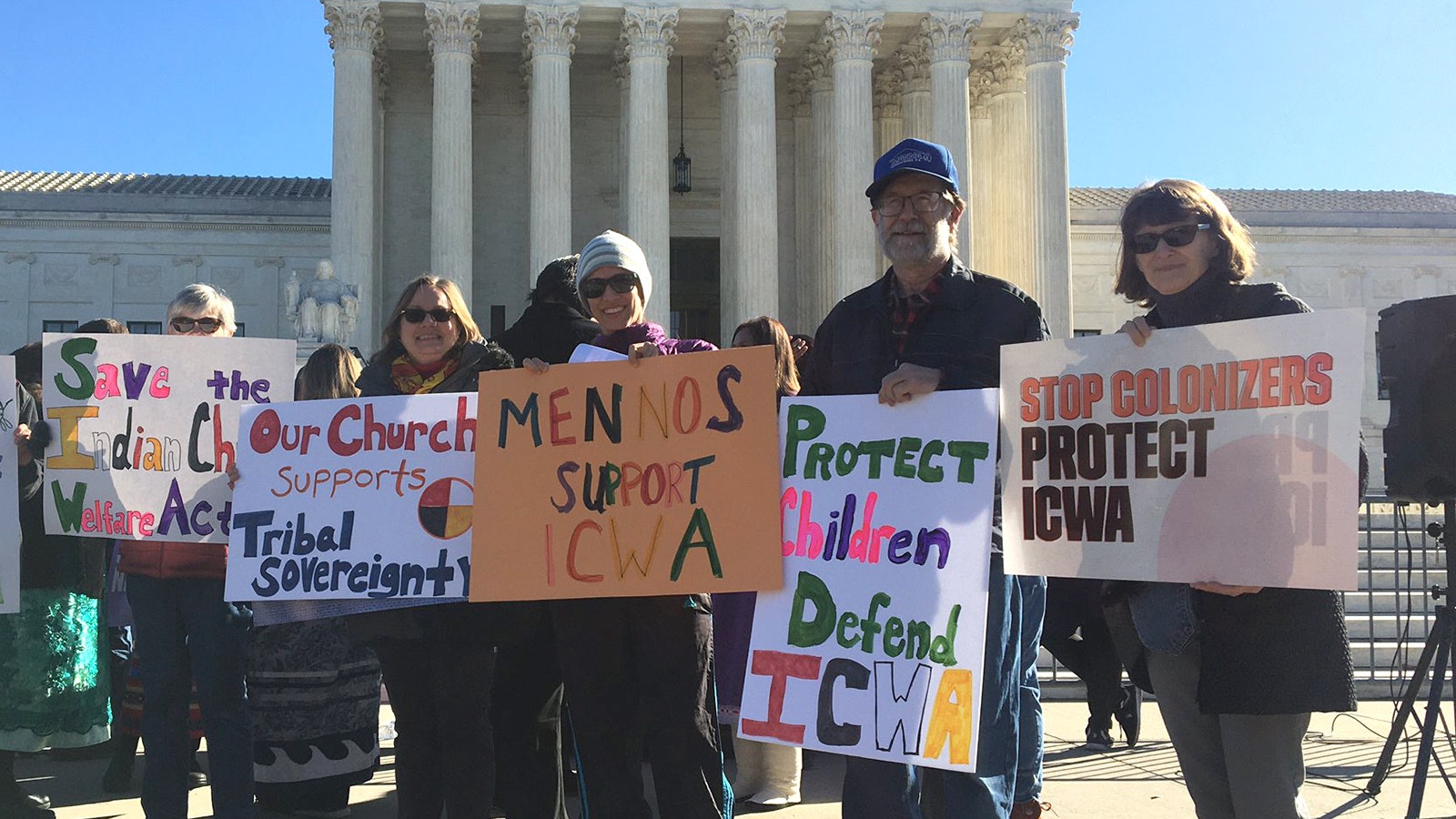

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act on Thursday, a 45-year-old federal law designed to keep American Indian families together by keeping Indian foster and adoptive children out of non-native homes.

Foster, adoptive and biological parents, along with the state of Texas brought Brackeen vs. Haaland to the U.S. Supreme Court last year, arguing that the Indian Child Welfare Act violates the sovereignty of states over family law, and is racist.

In a majority opinion by Justice Amy Coney-Barrett, the high court rejected those arguments with a 7-2 ruling.

Children, Not Commodities

The U.S. Constitution gives Congress authority to regulate commerce with foreign nations, between states and with Indian tribes.

Petitioners challenging ICWA said the commerce clause can't justify the law, because “children are not commodities that can be traded.”

American Indian children taken into protective custody in many cases must be placed with an Indian family or Indian-run group home if one is available, rather than with any non-native foster family. The mandate applies to American Indian children who live off reservations as well as on them.

The petitioners argued that Congress justifies its law under the commerce clause, which treats children as commodities. This argument is “rhetorically powerful, (but) ignores the Court’s precedent interpreting the Indian Commerce Clause to encompass not only trade but other Indian affairs,” wrote Barrett, referring to earlier Supreme Court cases.

In other words, the authority of Congress to regulate Indian tribes’ commerce also allows it to determine foster-care and adoptive placement for American Indian children, including those living under state jurisdiction.

“In a long line of cases, we have characterized Congress’ power to legislate with respect to Indian tribes as ‘plenary and exclusive,’” wrote Barrett.

“Virtually all authority over Indian commerce and Indian tribes lies with the federal government,” she added, quoting from a 1996 case.

State Sovereignty Argument

The petitioners argued that ICWA violates the anti-commandeering doctrine barring the federal government from using state agencies to fulfill its schemes; and that ICWA violates the 10th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which guarantees to states the powers not specifically enumerated under the federal government.

Barrett said the anti-commandeering doctrine doesn’t invalidate ICWA because state courts historically have, and must, enforce federal laws — and state courts oversee ICWA cases.

And the petitioner, in this case the state of Texas, failed to show that ICWA specifically targets the state’s legislative and executive branches to do Congress’ bidding.

Barrett noted that ICWA applies to private and state agencies alike, and therefore the petitioners failed to make a clean 10th-Amendment argument that the law subverts state sovereignty.

“Legislation that applies ‘evenhandedly’ to state and private actors does not typically implicate the Tenth Amendment,” wrote Barrett.

No Racism Argument Today

ICWA has special provisions for kids in Indian foster-care and adoption cases that state family laws typically don’t have.

For example, a Wyoming court can terminate a non-native parent’s right to parent her child if someone makes a clear and convincing showing of evidence that she abused or neglected that child, and that she could not be rehabilitated and reunified with her child.

But under ICWA, a court can’t terminate an American Indian parent’s right to her child without showing that evidence beyond a reasonable doubt, which is a higher standard. It is therefore generally more difficult to terminate the rights of an abusive or neglectful parent if that parent is an American Indian.

The petitioners challenged ICWA as racist, saying it violates the Constitution’s promise of equal protection.

Barrett and the majority would not humor that argument, because the families seeking relief and the state of Texas don’t have standing to raise it, according to the majority opinion.

Texas “has no equal protection rights of its own,” wrote Barrett, citing an earlier case, “and it cannot assert equal protection claims on behalf of its citizens … against the Federal Government.”

Texas got creative, Barrett continued, and launched an “unclean hands” argument, saying that ICWA requires it to “break its promise to its citizens that it will be colorblind in child-custody proceedings.”

Barrett said this argument doesn’t show a concrete harm caused by the alleged federal overreach.

The majority justices rejected Texas’ racism arguments for lack of standing.

Because You Sued The Wrong People

The majority also rejected the arguments of the suing foster families, adoptive families and biological parents, that ICWA disadvantages non-Indian would-be parents by making them the last resort for placement of Indian foster and adoptive children.

The families named the wrong respondents in their case, wrote Barrett.

State agencies enforce ICWA for the federal government, the opinion says, so the respondents can’t win relief for the alleged racism by asking the Supreme Court to block the federal government’s — rather than the state agencies’ — actions.

The families would have had to apply for a block on the state agencies’ enforcement of ICWA in order to win relief, which they did not do.

“(Redress of grievances) requires that the court be able to afford relief through the exercise of its power, not through the persuasive or even awe-inspiring effect of the opinion explaining the exercise of its power,” wrote Barrett, referencing a 1992 Supreme Court case.

The majority opinion does not discuss whether the law itself is racist. It denies that argument for lack of standing.

The high court upheld ICWA and ordered the Fifth Circuit federal court to vacate its earlier decision overturning part of the law, for lack of jurisdiction. The Fifth Circuit had ruled that prioritizing any Indian tribe (not just the child's own tribe) and any Indian-run group home over non-Indian foster homes violates the equal protection doctrine.

Thomas And His Dissent

Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito were the only dissenters.

Thomas in his dissent railed against what he cast as the ambiguity of the high court’s longstanding guarantee of Congress’ “plenary power” over Indian tribes and “trust relationship” toward them. Those concepts, said Thomas, aren’t rooted in the Constitution, which guarantees Congress only treaty-making, commerce and foreign powers regulation authority with respect to Indian tribes.

“The Indian Commerce Clause is about commerce, not children,” wrote Thomas. “The Treaty Clause does no work because ICWA is not based on any treaty.”

And the foreign-affairs power shouldn’t uphold ICWA, Thomas asserted, because child custody is a domestic matter, especially with respect to Indian children living off-reservation under the jurisdiction of various states.

“There is no reason to extend this ‘plenary power’ to the situation before us today: regulating state-court child custody proceedings of U.S. citizens, who may never have even set foot on Indian lands, merely because the child involved happens to be an Indian,” wrote Thomas.

Justice Thomas derided the majority’s cited case, U.S. vs. Kagama, as overlooking the Constitution.

The Kagama court insisted that the federal government take an authoritative, guardian position over Indian tribes “because of ‘their very weakness and helplessness,’” wrote Thomas.

The court’s bleak characterization of Indian tribes and their self-reliance abilities led it in 1886 to expand Congress’ power over Indian people, Thomas’ dissent indicates.

A line of cases have since deferred to the Kagama court. Thomas asserted that those cases are fumbling for a nonexistent constitutional basis.

James Madison and John Rutledge proposed twice while drafting the U.S. Constitution to give Congress more power over Indian tribes than the plain wording of the commerce clause suggests, wrote Thomas, but the convention rejected both those offers without debate.

Incomplete

Thomas agreed with Barrett’s majority, however, that the petitioners’ arguments were incomplete, especially because the petitioners didn’t challenge what Thomas called the weak canon of case law from which they hoped the court would depart to overturn ICWA.

“While I share the majority’s frustration with petitioners’ limited engagement with the Court’s precedents, I would recognize the contexts of those cases and limit the so-called plenary power to those contexts,” said Thomas, meaning in part that, even if he respected Kagama and its progeny, the justice does not believe they justify ICWA’s special regulation of Indian children who have never lived on a reservation.

Not You, Texas

Thomas said other states may still summon better arguments to challenge ICWA.

“If there is one saving grace to today’s decision, it is that the majority holds only Texas has failed to demonstrate that ICWA is unconstitutional,” wrote Thomas.

Also, Barrett’s majority declined to disturb the Fifth Circuit’s conclusion that ICWA doesn’t violate states’ sovereignty, but the majority did not officially declare ICWA constitutional under that part of the Constitution.

Clair McFarland can be reached at clair@cowboystatedaily.com.