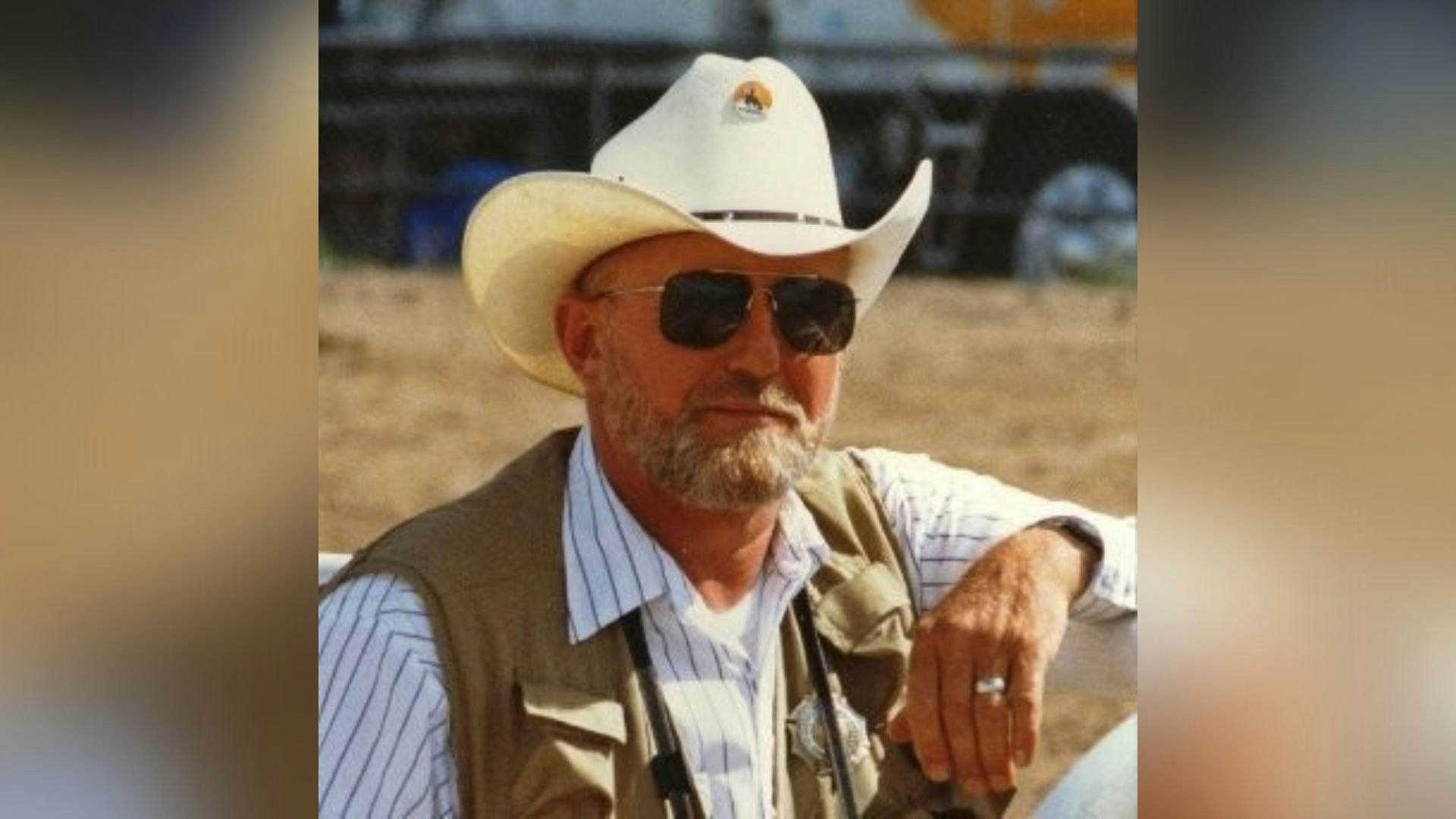

Wyoming lost one of its most passionate ambassadors May 15 when 89-year-old Randy Wagner — photographer, administrator, motorcycle enthusiast and Wyoming travel ambassador — died while in hospice care in Cheyenne.

For more than 60 years, Wagner was a towering presence in the travel and rodeo industries in Wyoming -- in more ways than one.

“Randy would describe himself as being ‘5-foot-19,’” said friend and colleague Gene Bryan. “He was 6-foot-7. I have a long history with ‘The Tall Guy,’ we shared a lot of experiences.”

Artist Chris Navarro, who befriended Wagner in the early 1990s, called Wagner a “gentle giant.”

“He was a great guy,” Navarro said. “I don't know anybody who didn't like him. He was just really generous.”

Journalism Background

Wagner grew up in Lander, and as a young man had two loves — motorcycles (he got his first at age 14), and photography. He had acquired a 1940s-era Super D Graflex camera, which he experimented with at night in his mother’s kitchen since he had no proper darkroom.

After graduating from high school, he attended the University of Wyoming with the intention of earning a degree in engineering.

“I quickly decided that journalism was my calling,” Wagner wrote in a biography featured in artist Chris Navarro’s book “The Art of Rodeo.” “The ‘J’ Department had a real darkroom with enlargers and all the right chemicals. I got hooked on the magic of photography and photojournalism.”

Wagner’s college career was interrupted in 1956, when he left to serve in the Army Corps of Engineers from 1956-58 as division photographer. After his return, he went on to graduate from UW in 1959 with a bachelor’s degree in professional journalism, which he put to use right away, Bryan said.

“He was an alumnus of the Laramie Boomerang,” Bryan told Cowboy State Daily. “He was there before me, and I was there (as sports editor) from 1960-1964.”

Documenting Wyoming

Bryan called Wagner a “world-class photographer,” first becoming aware of his work as chief photographer for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department in the early 1960s.

But it was when Bryan went to work for the state of Wyoming in 1967 that he began working directly with Wagner.

“Randy and Pete McNiff were two of the first staffers at the Wyoming Recreation Commission, which now is known as the State Parks and Cultural Resources office,” said Bryan. “And while he was there, Randy did a documentary on the Oregon Trail. So in addition to everything else, he was probably one of the renowned authorities on our historic trails in Wyoming.”

When the staff photographer at the Travel Commission retired, then-director Frank Norris hired Wagner away from the Recreation Commission.

“When he became our staff photographer for the travel commission, I got to work with him hand-in-glove,” said Bryan.

Serving The State

But when Norris died in 1978, Wagner took a big step forward.

He was named the new director of the Wyoming Travel Commission, during which time he served on the board of directors of the Travel Industry Association of America and was named to that organization’s Executive Committee and Corporate Strategic Task Force. Additionally, Wagner was elected chairman of the National Council of State Travel Directors and named U.S. Travel Director of the Year in 1984.

“He got Wyoming involved in the international marketing of tourism,” said Bryan. “He hired Chuck Box — C.J. Box — as his international marketing manager.”

In 1988, Bryan found himself once again following in Wagner’s footsteps, replacing Wagner as director of the Travel Commission when he stepped down that January.

But Bryan didn’t let Wagner stray too far from service to the state of Wyoming. Shortly after Bryan took the mantle of the Travel Commission, the devastating Yellowstone fires of 1988 became front-page news.

“The first thing I did is I hired Randy under contract to get to that park as soon as he could and start photographing,” said Bryan. “So we had documentation of the fire through that whole summer and fall, thanks to Randy.”

Additionally, Bryan said Wagner was a “world-class” writer, when he put his mind to it.

“He wrote some articles for me when I was editing the monthly newsletter,” said Bryan. “They were just damn good. He had gone on a pack trip into the Wind Rivers with some folks, and that article still sticks in my mind as one of the finest pieces of writing I've ever read.”

Rodeo Photographer

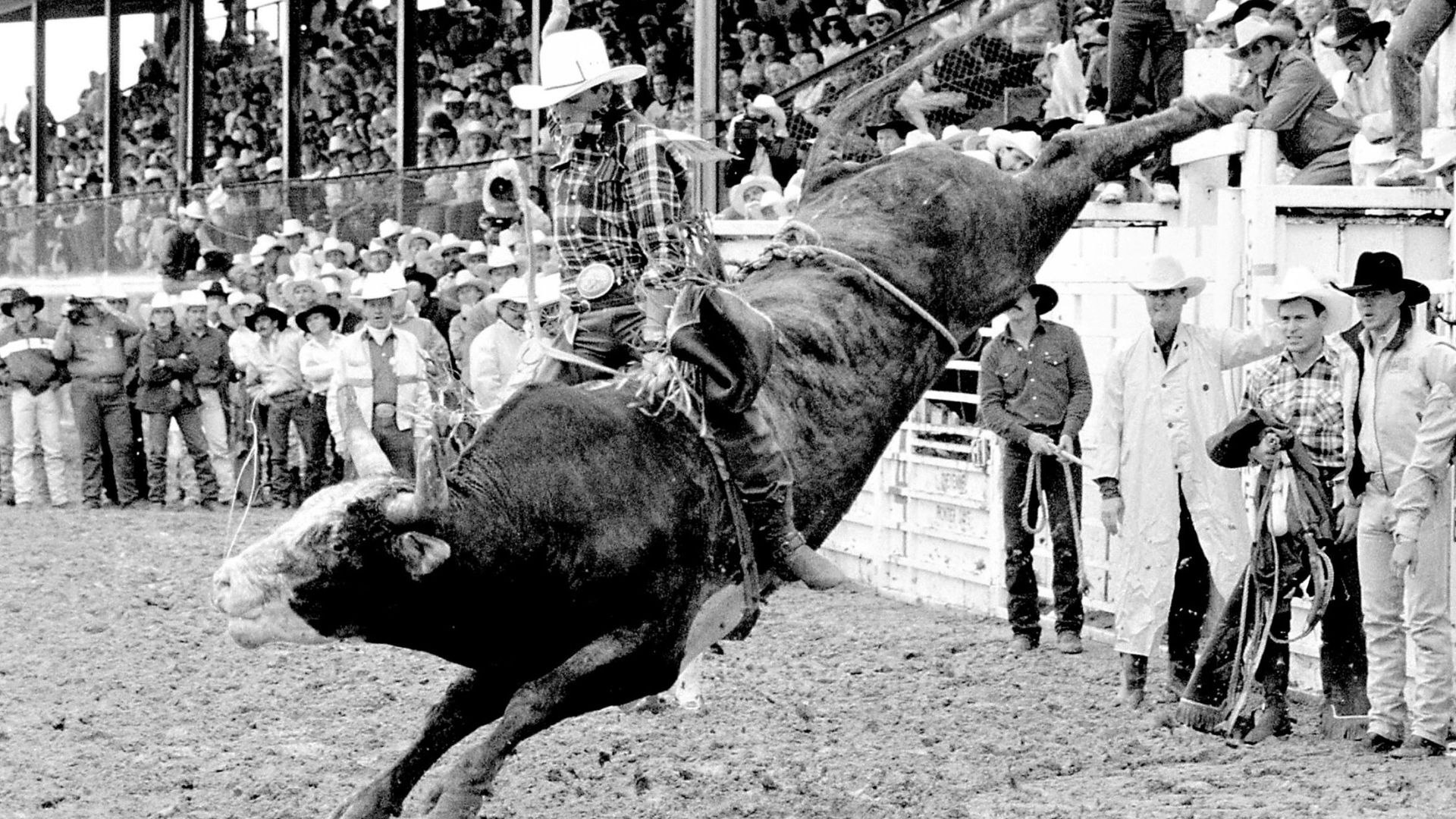

Even while serving as the director of the Wyoming Travel Commission, Wagner couldn’t leave his beloved camera untouched.

Beginning in 1978, Bryan served as the executive director for Cheyenne Frontier Days, and Wagner was his go-to photographer.

“Randy was our unofficial staff photographer during that whole period,” said Bryan. “And he was not a trained rodeo photographer, but I can say without fear of contradiction that he was absolutely one of the best rodeo photographers that ever walked the arena.”

Wagner was inducted to the Cheyenne Frontier Days hall of fame in 2012, in large part because of his work as a photographer for the “Daddy Of ’Em All.” For 30 years he was the event’s official photographer, and even after retirement continued to take up-close-and-personal photographs of the action on a volunteer basis.

“He's the one that developed that rodeo photography pit (at Cheyenne’s Frontier Park),” said artist Chris Navarro, who collaborated with Wagner on “The Art of Rodeo,” a history of Cheyenne Frontier Days. “But he designed it for him, and he was 6-7, so most average height people need a little stool to get (good shots).”

Lane Frost’s Last Ride

A memory that Wagner carried with him to the end was of a hot summer day in 1989, when a Frontier Park arena record was set, and a rising star came crashing to the ground. Wagner wrote about that day in Navarro’s “Art of Rodeo.”

“If there was one rodeo that will forever stand out in my memory, it would have to be the Sunday Finals in 1989. On that miserable rainy-day Marty Staneart rode the champion bull, Mr. T, to an arena record 93 score, winning the event. It was the first time in over 150 attempts that Mr. T had been ridden for the full eight seconds. It was the highlight of the day. Perhaps of the entire rodeo season. The low point would come minutes later when Lane Frost made an almost equally sensational ride followed by a bad dismount. The bull horned him in the back as he was trying to get to his feet. He was dead within minutes. It happened right in front of me and I will never be able to wipe it from my memory. I wish I could.”

Navarro first met Wagner while working on his bronze sculpture of Lane Frost at Frontier Park. At the time, Wagner was a volunteer photographer for the rodeo.

“I always saw him carrying around a camera,” said Navarro. “So he helped me take some pictures of my Lane Frost monument. It was really helpful, and I asked him if I owed him anything, and he said no. And I said, ‘Wow, he's a good guy.’”

Navarro was so impressed with Wagner that when he decided to publish a book about Cheyenne Frontier Days, he enlisted Randy’s help.

“When I started this idea of doing this book, I knew he had shot all the rodeo footage back in the ’60s up to the 2000s,” said Navarro. “He had thousands of photographs.”

Dangerous Perspective

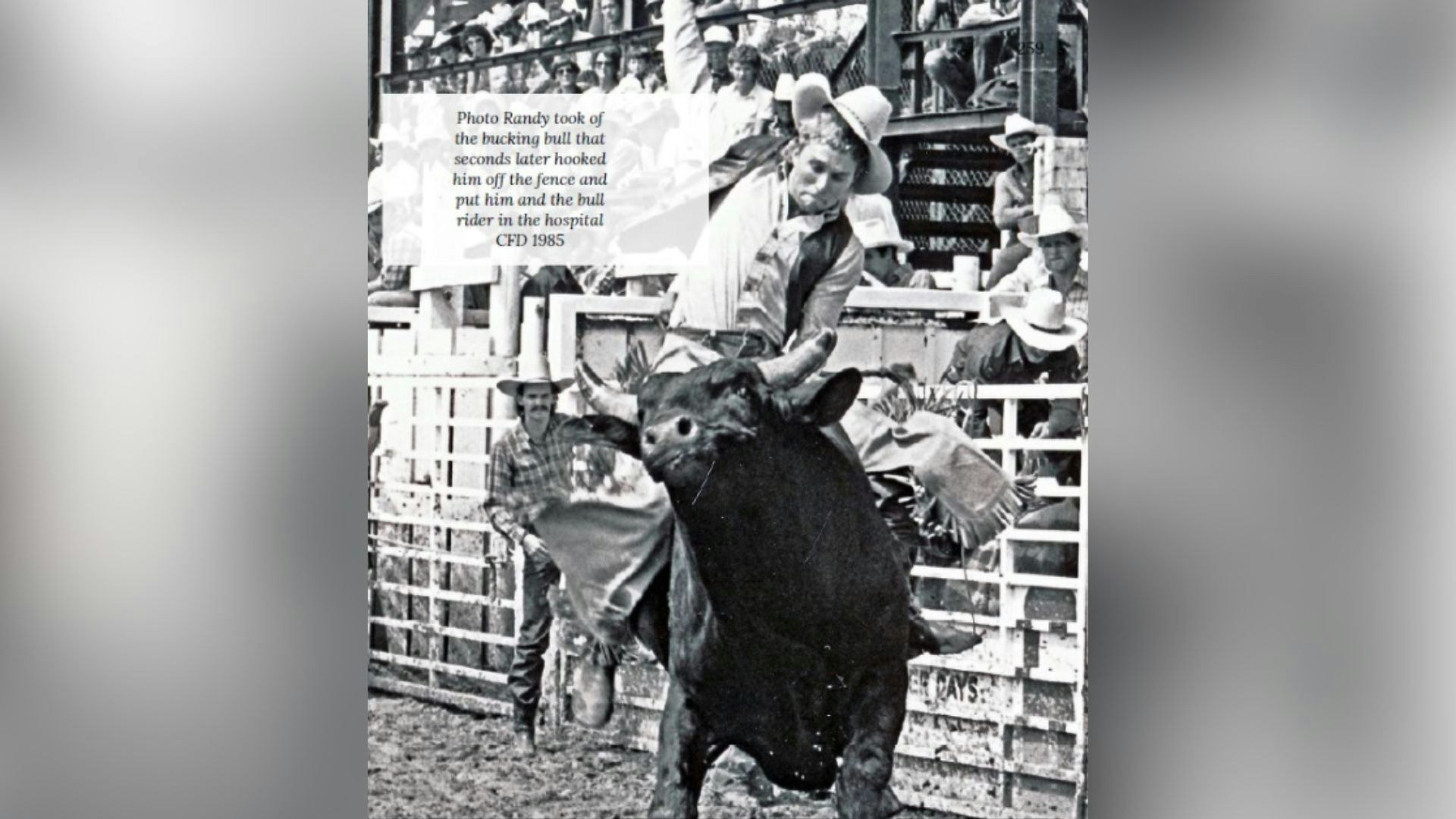

But being a rodeo photographer was not without its dangers. In Navarro’s book, Wagner related the story of his own savage goring by a bull in 1985.

“Somehow, I managed to photograph over 400 CFD rodeos during 45 years in the arena without incident ... except for 1985. That year I got careless on opening day and a bull picked me off the fence and turned me into a frisbee. Bobby Romer came to the rescue (just as the bull was trying to break my back) and the medics sent me to the hospital, along with the cowboy who was riding the bull. I spent the next five days there and left with a lot of stitches but still able to sing baritone. The major casualties of the wreck were two perfectly good Nikon cameras.”

But amazingly, Wagner managed to capture a photo of the bull that nearly ended his life, which was included in “The Art of Rodeo.”

Biker At Heart

Anyone who knew Wagner personally could attest to his lifelong love of motorcycles, beginning at age 14.

“Randy rode motorcycles from the time he was old enough to get his license,” said Bryan. “In fact, he had the first motorcycle license plate in Fremont County: 10-1. And he kept it right up to the end.”

Starting in the early ’70s, Wagner and his wife, Betty, traveled with friends from the Rocky Mountains to Nova Scotia. According to his obituary, Wagner logged more than 700,000 miles on his bike, traveling to all the lower 48 states, and took tours of Europe, New Zealand, Mexico, Canada and Switzerland.

Wagner’s Legacy

Randy’s wife was by his side for 67 years, but died in January last year. The couple had four children – two of them, daughters Kary and Kriste, are married with their own families. Tragically, another daughter, Kelly, and their only son, Kraig, preceded both their parents in death.

Wagner’s legacy lives on, though, in his remaining children and grandchildren, as well as his collection of photographs and personal items that are being preserved at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center in Laramie and the Cheyenne Frontier Days Old West Museum in Cheyenne.

“He was just a giant in more ways than one,” said Bryan. “Physically, of course, and as a photographer, as a travel marketer, as a historian. And he was just one of those people that didn't seek accolades for it — he just liked doing the work.”