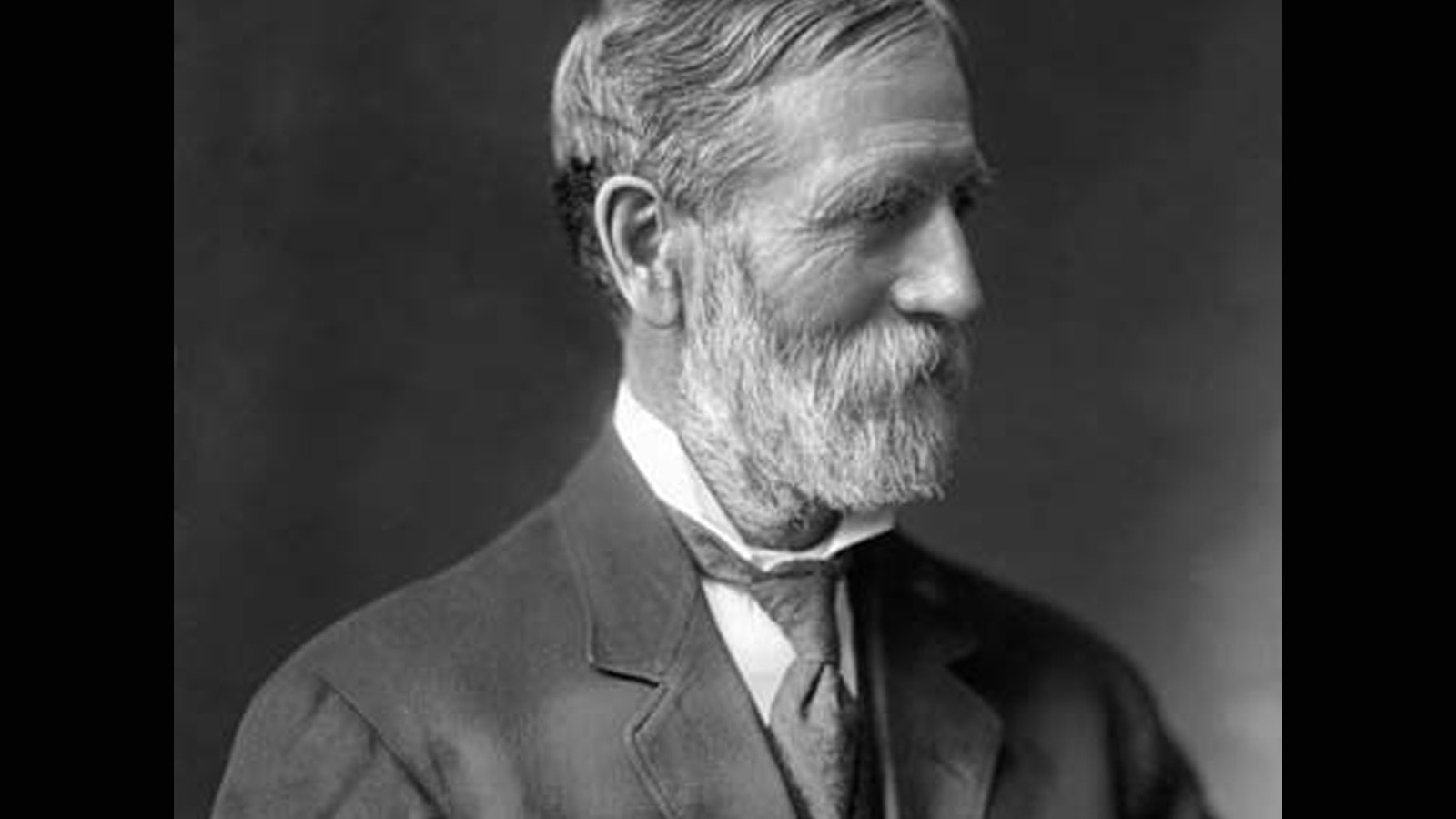

Photography, steam cars, and the haunted hotel that inspired the cult horror classic “The Shining” all have one thing — or one man, rather — in common.

That is Freelan Oscar Stanley, who some have described as the Tony Stark of Estes Park. Stark is the inventive genius behind the Ironman suit of Marvel Comics fame. But unlike Stark, F.O. Stanley is 100 percent real.

He built The Stanley Hotel, which is a two-hour drive from Cheyenne. Among its claims to fame is being the place where Stephen King’s novel “The Shining” was inspired. But Stanley is not just the reason there’s such a grand, world-famous hotel in Estes Park. He and his twin brother, Francis Edgar, are together responsible for inventions that helped change the world we all live in.

The brothers were born in 1849 in Maine and remained an inseparable pair throughout their lives, until Francis died in an automobile accident in 1918.

A big part of what the two did together for fun was to invent new things, and it started at quite a young age. The two were 9 years old when they started their first business together refining and selling maple sugar.

By age 11, the two had learned to make high-quality violins, which are still sought after today and are worth thousands of dollars. Devotees say they rival a Stradivarius in sound quality. Both boys kept making violins as a hobby throughout their lives.

Maple syrup and violins, of course, were not their world-changing inventions. These were just warmups while the men were still children.

The Real Kodak Moment

When F.O. Stanley’s drawing set factory was destroyed by fire after just a year in operation, his brother Francis suggested they work together in Francis’ photography studio in Maine.

There, the two brothers perfected an entirely new process for making photographic plates, establishing the Stanley Dry Plate Company in 1885.

Where before, wet plates were made by hand at a rate of 60 per hour, the brother’s new dry-plate method could crank out 60 plates a minute. This was a tremendous leap forward for photographers everywhere, and it made the brothers a small fortune.

But the brothers soon became enamored with steam cars. So, they sold off their invention to one George Eastman of Kodak, for somewhere between $565,000 and $800,000 — a princely sum at the time — so they could focus on their latest and greatest new invention, the Stanley Steamer.

But their photographic invention would be integral to many future advancements made by Kodak, including the invention of roll film. That in turn, helped bring us all those easy-to-use, handheld cameras so good at snapping our very own Kodak moments.

A Stanley Promise

One of the reasons the Stanley brothers took to the steam engine so keenly had to do with a promise Francis Stanley had made to his wife.

He and Freelan had become fascinated with bicycles at the time, but when Francis’ wife fell off and hurt herself trying to ride one, she vowed never to do so again.

So, Francis promised to build something the two of them could ride in together, in safety and comfort.

Francis and his brother began with simply building what looked like the shell of a fancy wagon, but lighter, and more agile. Stanley Steamers would ultimately have light wooden bodies mounted on tubular steel frames, with shock-absorbing springs.

But how to power this new conveyance?

The Stanley brothers considered three possibilities, electricity, combustion, and steam.

The latter, they decided, was the best way to go.

They built a vertical fire-tube boiler, reinforcing it by wrapping piano wire around it, for a light-weight shell that could withstand up to 250 psi.

Safety valves on the boiler insured the boilers were safe from explosions. The joints would also give out long before the shell, ensuring there could be no explosions. In fact, there are no documented cases of any Stanley boilers exploding.

The Stanley Steamer included an engine with double-acting cylinders, seated side by side, and the drive was transmitted directly via a crankshaft using a chain.

The Stanley Steamer was fast for its day. In 1906, a modified Stanley Steamer set a land-speed record of 127.66 mph with Fred Marriott as driver. That record held for four years — then quite an accomplishment with previous records falling away sometimes every hour — and would not be beaten by another steamer until 2009.

At one point, 125 different firms were making steam-powered automobiles, but the days of steam-powered automobiles were numbered.

One of the big problems with steam-powered vehicles was the time it took to light the pilot, fire up the boiler, and build up enough pressure for the contraption to move.

In the early days, though, when gas-powered vehicles still required hand-cranking, steam power remained competitive. They were also cleaner and considered more reliable than gas-powered cars.

The electric self-starter, invented by Charles Franklin Ketterering, changed the game.

Ketterering’s electric self-start was introduced on Cadillacs in 1912, and patented three years later. The idea was soon standard on all gas-powered vehicles.

After that, gas-powered cars quickly put steam-powered cars in a permanent rear view mirror.

The Stanley brothers still swore by their Steamers for the rest of their lives, though, and the Steamers were often used for transporting guests to F.O. Stanley’s hotel in Estes Park.

Building The Stanley Hotel

When F.O. Stanley arrived in Estes Park in 1903, it was under a death sentence. He’d been told by his doctor that he had tuberculosis, and likely just six months to live.

Stanley chose Estes Park because he wanted to die somewhere beautiful. It was also hoped the mountain air would alleviate his suffering. His doctor had compared the atmosphere in Estes Park to Davos, Switzerland, which at the time offered a posh resort for Europeans with tuberculosis.

Instead of dying, however, F.O. Stanley made a remarkable recovery. He put on 29 pounds that first summer, and his coughing all but went away. When his doctor visited at the end of the summer, he pronounced Stanley cured. The Rocky Mountain air, sweetened by ponderosa pines, had done it.

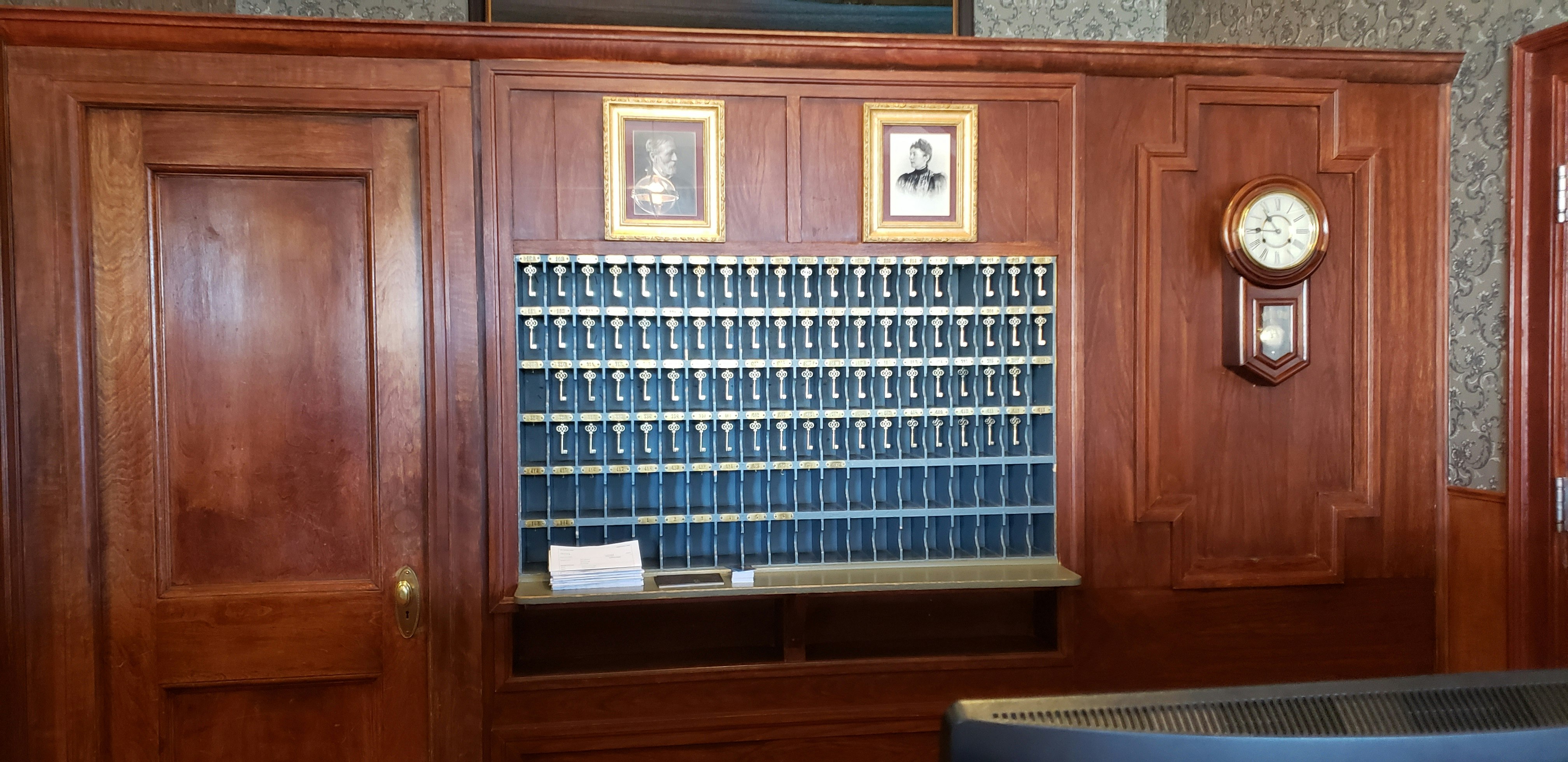

The Stanleys began to spend every summer in Estes Park, and soon set about building The Stanley Hotel, which opened in 1909 to much fanfare.

Although the hotel did attract many wealthy and famous guests from far and wide, it was never a money maker for F.O. Stanley. He is reported to have said that he would “arrive in the spring and bring thirty thousand dollars to operate and go back in the fall with ten or fifteen thousand left.”

Eventually, Stanley sold the hotel to the Estes Park Hotel Company, owned by Roe Emery, in 1930.

After Emery’s wife died in an automobile accident in 1943, the hotel would change hands numerous times, until it was purchased out of bankruptcy by Grand Heritage Hotels in 1995 for $3.1 million.

Principal owner John Cullen has said his plan for the hotel is to raise The Stanley to at least a four-star rating. The hotel recently completed a major remodeling to help it achieve that goal.

Not Just The Hotel

F.O. Stanley did much more than just build a hotel, however. He helped found the Estes Park Protective and Improvement Association (EPPIA), which in turn backed Enos Mills’ efforts to establish Rocky Mountain National Park in 1915.

EPPIA’s other efforts included a fish hatchery to stock local streams, for which Stanley donated one of the three ponds, as well as lobbying for construction of Fall River Road and its extension across the Continental Divide, and reintroduction of elk to the region. The first 29 elk, which were transported from the area of today’s Yellowstone National Park to Estes Park, were pastured on some of Stanley’s land.

As part of building The Stanley Hotel and his summer home in Estes Park, F.O. Stanley also built a hydroelectric power plant on Fall River. When the townspeople wanted electrical service, too, he agreed to provide it based on the number of light bulbs used — but he provided power to Estes Park streetlights at no charge.

Much like The Stanley Hotel, the money he received from the electrical service he provided didn’t cover all his costs. Stanley made up the difference out of his own pocket.

He also provided land for a dump to dispose of the town’s refuse, and donated land for the installation of a new sewer line. He helped organize the Estes Park Water Company to improve water access for residents, then later sold it back to the town.

The Stanley Park, meanwhile, was developed on land that F.O. Stanley donated to the city. The park includes the fairgrounds, a school complex, gun club, and city and county offices, among several other facilities.

F.O. Stanley was also quite well known for helping pay for the college education of many Estes Park children who otherwise couldn’t have afforded to go.

His generosity came from a simple belief. He believed a happy life was the result of making others around you happy.

He gave much of his fortune away over his lifetime. When he died in 1940, and his will was probated in 1942, records show he had remaining assets of just over $51,000. That figure included his summer home in Estes Park, located on Wonderview Avenue.

Renée Jean can be reached at Renee@CowboyStateDaily.com