By virtue of vastly different state wolf management policies, the O’Toole family ranch is stuck between two worlds.

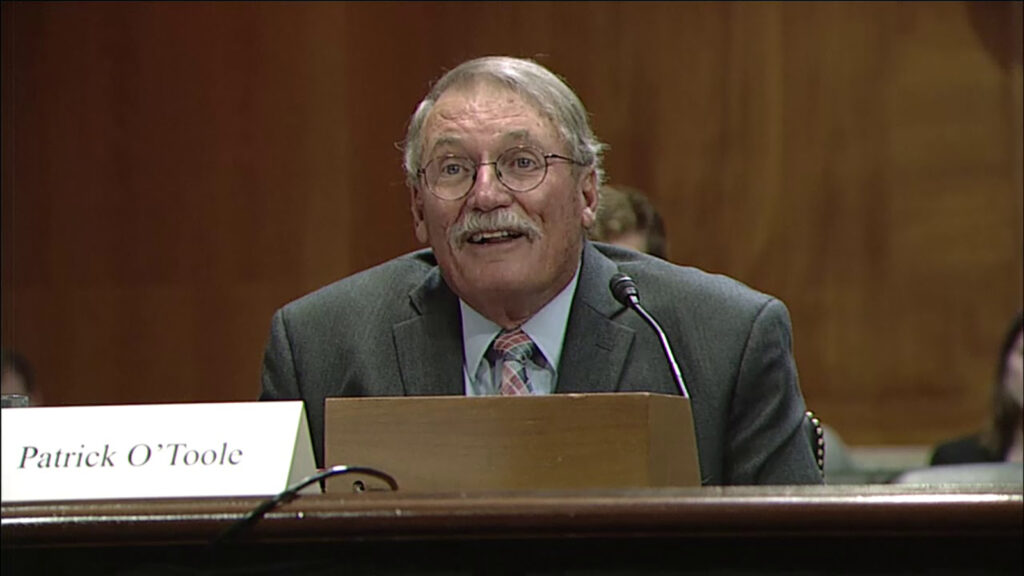

“So, you’ve got two sets of state rules as they relate to wolves, and they couldn’t be any more different,” Pat O’Toole told Cowboy State Daily.

O’Toole, who is a former Wyoming lawmaker and longtime conservationist, said he feels gratitude and foreboding when it comes to the future of the Ladder Ranch. That’s his family’s sheep and cattle operation, which straddles the Wyoming-Colorado state line roughly 50 miles north of Steamboat Springs, Colorado.

“I’m a very lucky guy,” he said. “My grandchildren are the sixth generation here (on the ranch).”

Bears and mountain lions already take a heavy toll on livestock and big game animals in the area, he said. That’s why O’Toole doesn’t see much good coming from Colorado’s decision to begin reintroducing wolves starting by the end of this year.

“Now, we’re bringing in another super-predator, with no regulations at all as it relates to the wolves,” he said.

Decades Of Controversy

Wolves were essentially wiped out in the Rocky Mountain West early by the early 20th century. A tenacious population in Minnesota was the species’ last holdout in the lower 48 states.

A seed population was reintroduced to Yellowstone Park in the mid-1990s. Those wolves soon established numerous packs and began expanding their range well beyond the park’s borders.

Over the decades since, there have been strong opinions and heated arguments over wolves and how to best manage them.

Some hailed how the packs had restored a healthy ecological balance to Yellowstone and the surrounding others. Others decried the toll packs were taking on livestock and big game animals.

Eventually, wolves reached Colorado.

A female is thought to have traveled more than 400 miles from northwest Wyoming before settling in North Park, Colorado. In 2021 she paired up with a male, which also had migrated from Wyoming. They soon had pups, forming the North Park pack.

‘Those Dogs Are Family’

Wolves remain under full Endangered Species Act protection in Colorado, meaning residents there can’t shoot them. And it wasn’t long before the North Park pack began killing livestock.

The pack made headlines again earlier this month when those wolves killed two dogs in rural Jackson County, Colorado.

O’Toole said his family uses border collies as working cattle and sheep dogs, just like Cisco, one of the dogs killed in Colorado.

The North Park wolves “are killing stock dogs and they’re killing livestock, and it’s a real mess,” he said. “We raise border collies, and they’re some darned good dogs. It’s heartbreaking to see one killed. Those dogs are family for ranchers.”

Cities Dictating Rural Policy

As O’Toole sees it, the decision to bring more wolves to Colorado highlights the sharp differences between Colorado’s urbanized Front Range on the east side of the Rockies and rural Western Slope, where the wolves will be released.

The wolf reintroduction was authorized by Colorado’s Proposition 114. It barely squeaked by voters Nov. 3, 2020, by a margin of 50.91% to 49.09%.

“This was decided, by less than a 1% margin, by the urban population on the Eastern Slope,” O’Toole said.

“I have serious questions about how one part of the state can vote negative on another part of the state,” he said. “What are we trying to do? Raise families and food. And now we’re the bad guys?”

Contradictory Management Policies

O’Toole said he doesn’t expect the return of more wolves to Colorado to go well.

“It’s just going to be a wreck,” he said.

And things could get particularly messy in his area when Colorado wolves range across the border into Wyoming.

“The Little Snake River crosses back and forth between the state line 32 times in this valley,” he said. “Our ranch is in both Colorado and Wyoming, as are many of our neighbors’ ranches.”

That means whether ranches can shoot wolves they think are threating their livestock or dogs will depend upon what part of the valley they’re in.

Under current plans, wolves in Colorado will probably remain fully protected for years to come, Colorado Parks and Wildlife spokesman Joey Livingston told Cowboy State Daily recently. Hunting might be part of a future phase of the Colorado wolf management plan.

During a recent public hearing on the matter in Denver, many Coloradoans said they don’t want wolves to ever be hunted there, while others said they favor it.

On the Wyoming side, wolves will be in the Cowboy State’s “predator zone,” meaning they may be shot on sight at any time.

An environmental group has threatened a lawsuit against the U.S. Forest Service over that policy. The Center For Biological Diversity claims the agency should forbid the killing of wolves on the Medicine Bow-Routt National Forest, which straddles the state line.

‘They’ll Travel 60 Miles In One Day’

If Colorado is to have wolves, it should have a management policy similar to those in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho – all of which allow wolf hunting, O’Toole said.

His family and other ranchers in the area should be able to protect their cattle, sheep and dogs on both sides of the state line, he said.

“The reality is, if you’re in the sheep business and the cattle business, predator control is a big part of what you do,” he said.

As it is, ranchers there already have their hands full with bears and mountain lions, so throwing in wolves that could be controlled on only one side of the state line could make things impossible, he added.

“We stopped grazing cattle on one mountain where were grazing for 100 years because we were losing so many calves to bears there,” he said.

O’Toole said he’s also incredulous about Colorado’s plan to give its new wolf packs at least a 60-mile “buffer zone” from state lines or tribal lands.

“They’ll travel 60 miles in one day,” he said.