One of the super-secret measures the United States government took during Japan’s balloon bomb attacks on America during World War II involved a few very good men.

Wyoming cowboys, to be exact.

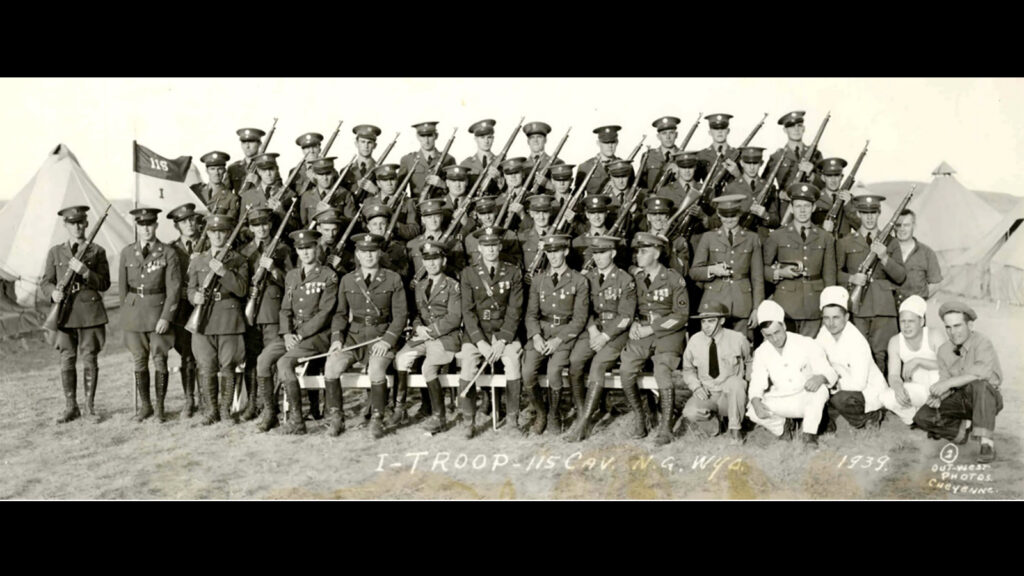

Atop thoroughbred horses some 17 hands tall, 960 Wyoming cowboys — from Casper, Cheyenne and all parts between — were deployed to Fort Lewis in Washington state as part of the 115th Calvary Regiment, just ahead of the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941.

Their mission was to patrol the West Coast on horseback, looking for any sign of invasion. They had counterparts from the Coast Guard — also on horseback — who patrolled the East Coast.

When Japan floated its balloon bombs to America in 1944, some soldiers involved in the coastal patrols recall being told about them, and were on the look-out for them as well, said Wyoming history buff Karl Brauneis, who has made a lifelong hobby of collecting stories about the 115th.

Horses? Really?

It may be a little puzzling to think of cowboys on a horse during World War II. There were, after all, airplanes and tanks then, as well as cars. Automobiles, in fact, had become fairly commonplace since the 1908 production of the affordable Model T Ford decades before the war.

But roads at the time were often still dirt, particularly in the West, and it didn’t take much rain to make them impassable to all but a horse.

“Any bad moisture would just turn everything into mud and ruts and you couldn’t get through it,” Brauneis told Cowboy State Daily. “You’d be stuck. So that’s the reason why in the West, the horse was still king up to World War II.”

Toward the end of the war, the regiments began to be “mechanized,” and after World War II, America built many new interstates, which put the shift from horse to automobile into a much higher gear.

Triple Nickels Also Helped

Because the 115th was sent to so many different theaters of war, it’s difficult to track their accomplishments or say how many would have been involved in scanning the skies for Japanese balloon bombs, Brauneis said.

Brauneis, a smoke jumper for the U.S. Forest Service, reached out to Cowboy State Daily after reading a story about the Japanese balloon invasion in 1944.

“The bomb thing was meant to start major fires in the northwest to drain manpower,” Braun said. “So, the smokejumpers became involved in that.”

In addition to some members of the 115th being on the lookout for balloon bombs, the Army also mobilized the 555th, known as the Triple Nickels. The all-Black parachute unit’s mission was to augment the Forest Service’s existing smokejumpers in case any balloon bombs were successful in starting fires.

Fortunately for America, the most opportune time for launching balloon bombs from Japan also corresponded with the wet and rainy season in the West.

Mother Nature herself had joined the mission of the 115th and the Triple Nickels to help suppress any major fires.

Best Of The Best

The 115th was highly trained and specialized, and well-known in that time as best in class, Brauneis said.

“These were all cowboys in the National Guard, so they rode horses all the time,” he said. “That’s part of what made them so good.”

There also was pretty specific training for both horse and cowboy.

Horses were conditioned to the sound of gunshots so they would not get nervous and buck, rear up or run away.

This process took about four to five weeks, according to an account told to Brauneis by Floyd Reed, who was recounting what his dad told him about the experience.

“They would start by having the horses loose in a big corral and walk around at a distance and shoot into the ground,” Reed wrote in a letter to Brauneis. “Each day, they would move closer to the horses and fire more often.”

Once the horses were accustomed to the noise, guns would be fired while the horses were on a lead, and then, finally, from horseback.

Only the best and calmest horses were chosen to continue on to the 115th regiment.

Couldn’t Really Aim

Cowboys, meanwhile, had to qualify for their service by hitting a target from 25 yards while jumping a 2-foot barrier.

Brauneis was told by Racy Clark, a well-known figure in the Lander area at the time, that there was a trick to aiming while on horseback.

“You couldn’t aim the gun,” Brauneis said, so what Racy taught his cowboys to do was to “push the gun toward the target and fire.”

Each soldier ran through a riding course to learn to shoot while on horseback, applying that advice to the task. Only those who succeeded could stay with the 115th.

Today, 100-mile treks on horses are considered something of an endurance sport for both horse and rider — but to those soldiers then, it was an everyday ride of no particular note. Brauneis recalls being told about a daylong ride of 80-some miles from Lander to Pinedale through Washakie Pass.

“People today have no concept or understanding of the skill level these guys had,” Brauneis said.

Their like may never be seen again, but it will forever be part of the Cowboy State legend, and that ever-popular cowboy mystique that has endured even world wars, surviving into the modern age.