While the recent incursion of Chinese spy balloons hovering over American air space took many by surprise, it’s not the first time balloons from Asia have invaded the United States.

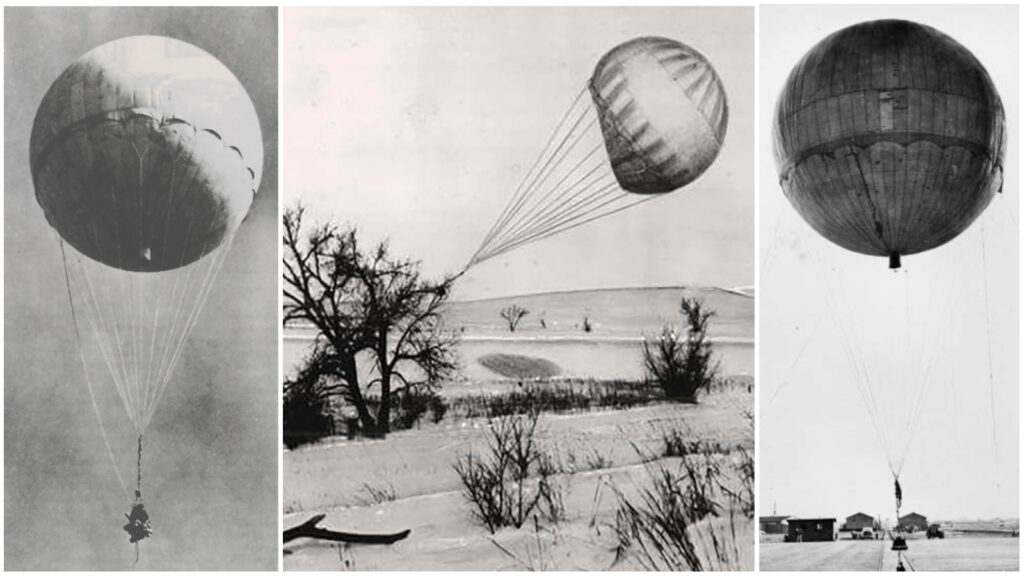

From 1944-45, the American West was the target of the first intercontinental weapons in human history when 9,000 balloons, with bombs attached, were sent 5,000 miles across the Pacific Ocean from Japan to the United States.

Their objective was to start wildfires and sow as much chaos as possible.

Thermopolis Among First Hit

Tiny Thermopolis in central Wyoming was among the first locations in the United States where a Japanese balloon bomb was reported after exploding.

According to a Dec. 14, 1944, newspaper article in the Thermopolis Independent Record, three men and a woman at the Ben Goe Coal mine west of Thermopolis saw a parachute lit up by flares. Moments later, they heard a whistling sound, followed by a loud explosion. Smoke then rose from a draw near the mine.

A nearby sheepherder, Louis Artman, told officials he saw the parachute land and that the flares burned for about 10 minutes after.

What was puzzling, though, was that neither reported hearing an airplane overhead.

It was a mystery.

The sheriff investigating the report found neither man nor parachute when he investigated. There were just fragments of a heavy bomb that had exploded about a mile and a half away from the mine near the Meeteetse-Thermopolis highway.

An investigator from the Casper air base also could find no trace of a parachute, but he took the bomb fragments away for further examination.

Six days later, authorities found a large paper balloon with a Japanese symbol and an incendiary bombs in Montana about 17 miles southwest of Kalispell.

The 70-foot fuse had sputtered out before the bomb could be ignited, which is why the bomb, which landed in an area prone to forest fires, had not ignited.

The balloon itself was made of high-quality paper treated with varnish. The contraption was engineered so that if the bomb had gone off, the paper balloon would have burned up, which helps explain what happened to the Thermopolis “parachute.”

It had been no parachute at all.

It was an entirely secret, new weapon in the war that was hitting primarily Western U.S. states. The landings started with California, Wyoming and Montana, but some even made it as far as Michigan.

An Engineering Feat

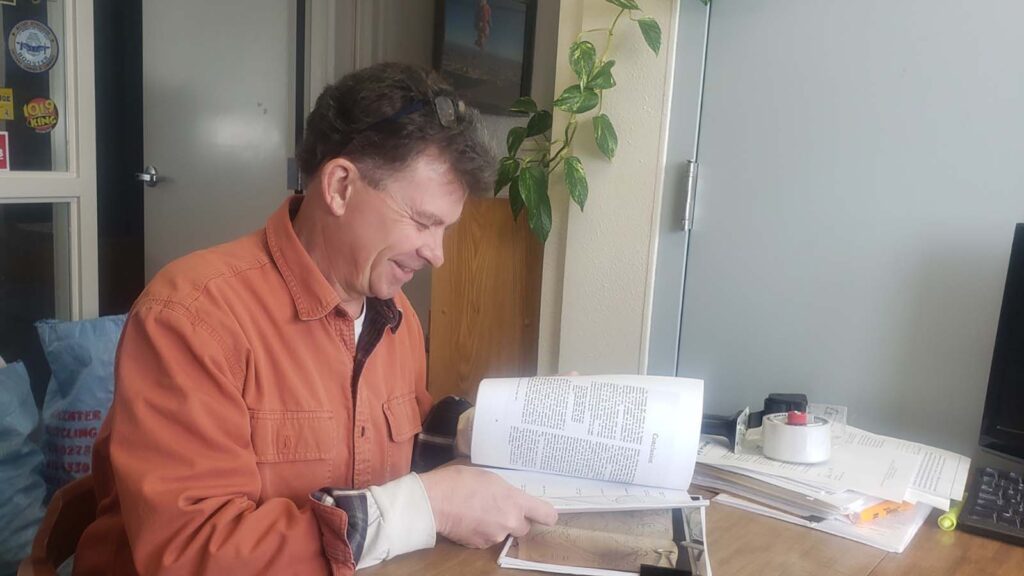

The armada of balloon bombs was, for its time, a noteworthy feat of engineering, said Don Day, a nationally recognized expert on balloons of all shapes and sizes and Cowboy State Daily’s meteorologist.

“I mean this whole story is actually quite amazing,” Day said. “The story on the Japanese side is amazing in terms of how clever and industrious they were to develop this program.

“And then, on the U.S. side, the ability to keep this under wraps so it didn’t cause panic, and then also to do the analysis to figure out where these were coming from, even down to the island that they were launched from.”

Schoolgirls Told No Secrets

The balloons were made in secret by Japanese school girls out of reams of handmade mulberry paper called washi.

Each paper panel was held together with a paste made from konnyaku, a Japanese potato, which had a little bit of coloring added so the girls could readily see how evenly the paste was being applied.

The laminated paper was inspected in a dimly lit room with frosted glass beneath it. Areas with less color showed up as insufficiently pasted, and were marked with chalk so they could be patched.

After lamination, the paper was soaked in a solution of soda ash, then water wash, and finally glycerin, to soften the paper.

Once dry, the panels were pasted together on a spindle form, upper half first, followed by the lower half. The two hemispheres were joined by a scalloped band that served as a suspension skirt.

Each balloon required 600 pieces of paper, all glued together by hand.

There was no room for any gas leakage if the balloons were to make a successful trip across the ocean. So, they were tested in large theater buildings and wrestling halls, which could readily house an inflated, 33-foot-diameter balloon. There weren’t enough of these, however, so additional buildings were built to test the balloons.

Balloons that showed no leakage after 24 hours were coated with a protective lacquer and were ready for the next stage of their journey.

The girls made 10,000 of these balloons in all. They were not told what the purpose of the balloons. And even when word did filter down about what the balloons were for, it was not believed. It seemed too absurd to be real.

The schoolgirls would tell no secrets.

Jet Stream Discovered

Sending a weather balloon 5,000-plus miles across the ocean at altitudes between 30,000 to 40,000 feet wasn’t a simple task in those days.

The jet stream wasn’t even a known quantity at the time, Day told Cowboy State Daily.

“In the 1940s, nobody talked about the jet stream,” Day said. “People knew that as you went higher the wind got stronger.”

But once U.S. intelligence officials showed meteorologists the track the balloons had followed, understanding began to quickly grow.

“They were like, ‘Oh my gosh, here’s a pattern,’” Day said. “This pattern indicates that they’re taking advantage of something we don’t know about yet. And that was really important, too, in the war.”

This new and interesting intelligence allowed military commanders to figure out, with more precision than before, things like fuel consumption. It was an important, unsung discovery, one that helped give America a new edge in the conflict.

Better Rubber And Radios

The Japanese balloon armada faced considerable engineering problems beyond the inexact science of forecasting wind speeds and weather.

Rubber components and electrical batteries of the time did not stand up well to the drastic changes in temperature and pressure they would face, and high-altitude explosives could become unreliable.

Nearly the entire supply of dry ice in Tokyo was diverted to researching and developing better components for the balloons.

The Japanese also needed to invent a better radio and batteries, so they could function in widely varying stratospheric conditions for at least 80 continuous hours.

The radio signals helped the Japanese determine the direction and altitude of the balloons, to calculate how long it would take them to reach America.

Approximating The Target

Each balloon was 33 feet in diameter and included an ingenious, automatic method for altitude control. A release fuse attached to two sandbags would ignite any time a balloon reached a preset minimum altitude of around 30,000 feet, cutting them loose.

That made the balloon lighter so it would rise back to the target altitude of 38,000 feet. This simple mechanism kept the balloons aloft for the entire trip, despite dramatic temperature changes between day and night.

Once all 32 sandbags had been discharged, the balloon would then light the bomb’s fuse and drop its load of bombs. Meanwhile, a small demolition charge would destroy the balloon itself.

The number of sandbags needed was calculated based on forecasted wind speed to approximate a balloon’s desired position over the North American continent.

Launch Day

There were just 50 days out of the year when weather conditions were favorable to successfully launching these balloons.

If they were sent up through rain or snow, or even some clouds, they could accumulate too much moisture. They would weigh too much and never achieve operating altitude, dropping their destructive payloads somewhere in the middle of the Pacific before ever reaching their target.

Filling the balloons with hydrogen was a dangerous task as well — and was even more dangerous on the windy days best for launching.

Each balloon took about 30 men to launch. Some included the advanced radios the Japanese had developed so that the flight pattern could be traced. That way, the Japanese could be reasonably sure the balloons were all headed in the right direction.

The radio payloads were set up to drop prior to reaching America, keeping them secret.

Balloons All Over, But Silently

After the report in the Thermopolis newspaper, the U.S. waged an elaborate and largely successful campaign to censor further reports of the balloons.

In Wyoming, there are recorded landings or recoveries in Basin, Manderson, Kirby, Casper, Powell, Glendo, Newcastle, Sundance, Cheyenne and Gillette. But no stories were written about them.

Law enforcement agencies across Wyoming and the nation had all been advised of the situation, as were newspaper editors, who voluntarily agreed not to publish any stories about them. That way, the Japanese would not know how many balloons were making it to America.

The Japanese saw the initial Wyoming report on the Thermopolis landing in a Chinese newspaper. Based on that report, Japanese generals had initially decided the idea was sound enough to continue — but they were ultimately disappointed when there were no further reports. So much so, they abandoned the program with at least 1,000 more balloons left to go.

But the voluntary censorship that had been successful in one respect also made it difficult to warn people of the danger. That led to the deaths of an Oregon woman and five neighborhood children, after they found one of the balloons and attempted to drag it from the woods.

The campaign of silence was then abandoned. A joint statement was issued by the U.S. War and Navy departments to describe the nature of the balloon bombs and warn people not to tamper with them.

That statement, though, was carefully measured, describing the attacks as “so scattered and aimless” that they presented no serious military threat.

An educational campaign was launched at the same time to warn everyone, particularly school children, of the danger of tampering with any strange objects found in the woods.

Behind the scenes, meanwhile, geologists worked to find the launch pad for the balloons, using the material in the sandbags.

Sand, it turns out, has a fingerprint made up of various minerals, coral fragments, fossilized diatoms, shells, and so forth. That helped scientists sleuth out likely launch locations.

Some Bombs Still Out There

Day estimates that just 10% of the 9,000 balloons that were launched reached America, or somewhere around 1,000.

But so far only 300 have been found.

“If you look at the wilderness areas that are in, like, Yellowstone and Montana, and huge wilderness areas in Idaho, Oregon and Washington, there’s a high likelihood these are still out there,” he said. “They’ve been covered by sediment and everything else.”

Day worked with the Discovery Channel during the COVID-19 pandemic to see if any more could be found.

“A lot of the places we told them to go, the roads were closed or they couldn’t (get there) because of COVID,” Day said. “The best places where we wanted to go, they couldn’t, so they kind of had their hands tied. With that said, though, I do tell people like hunters and hikers and stuff, just don’t assume it’s old mining or logging equipment that was left behind from a long time ago.”

Modern Technology Makes Balloons Scarier

While the Japanese program had very little precision in what targets balloons could hit and the objectives they could achieve, that’s not as true for today’s balloons.

“It’s actually kind of cool, but as evil and as nasty as that was, to relate it to what’s going on currently with the Chinese balloons and stuff that is well-engineered, well-thought-out, things like this are dangerous,” Day said. “They potentially have a lot of things that you can do and go quite a ways without being detected.”

Today’s balloons can even be remotely controlled to a degree by satellite.

“The miniaturization of the electronics now allows you to pack a lot more intelligence in terms of making these things smart balloons,” Day said.

That has media outlets already writing stories about the potential for more offensive military objectives than simply spying. And, in fact, a balloon bomb campaign happened not so very long ago in Israel, Day said, where big red party balloons, attractive to children, were reportedly flown into Israel with small bombs on them.

With such new capabilities for sophisticated military balloons masquerading as harmless weather balloons, that’s likely to have an effect down the line on all sorts of balloon activity in the United States, ranging from commercial flights that are planning to take people on near-space adventures, to simple hobbyists who just think balloons are fun to launch and follow while the balloons travel around the world.

“There’s a lot of people who just want to do stuff for fun, and they’ve been able to do that, but they might not be able to anymore,” Day said. “And, in my opinion, that’s probably an over-reaction, but it is what it is.”