When news broke last week that a new planet had been found that’s similar to Earth in its size and orbits within the “habitable zone” of its star, the discovery was hailed by NASA as significant.

A lesser-known fact, though, is that the spectrometer on the satellite that first identified the sphere was designed and built in Wyoming by a pair of University of Wyoming astronomers – Dr. Mike Pierce and Dr. Hannah Jang-Condell.

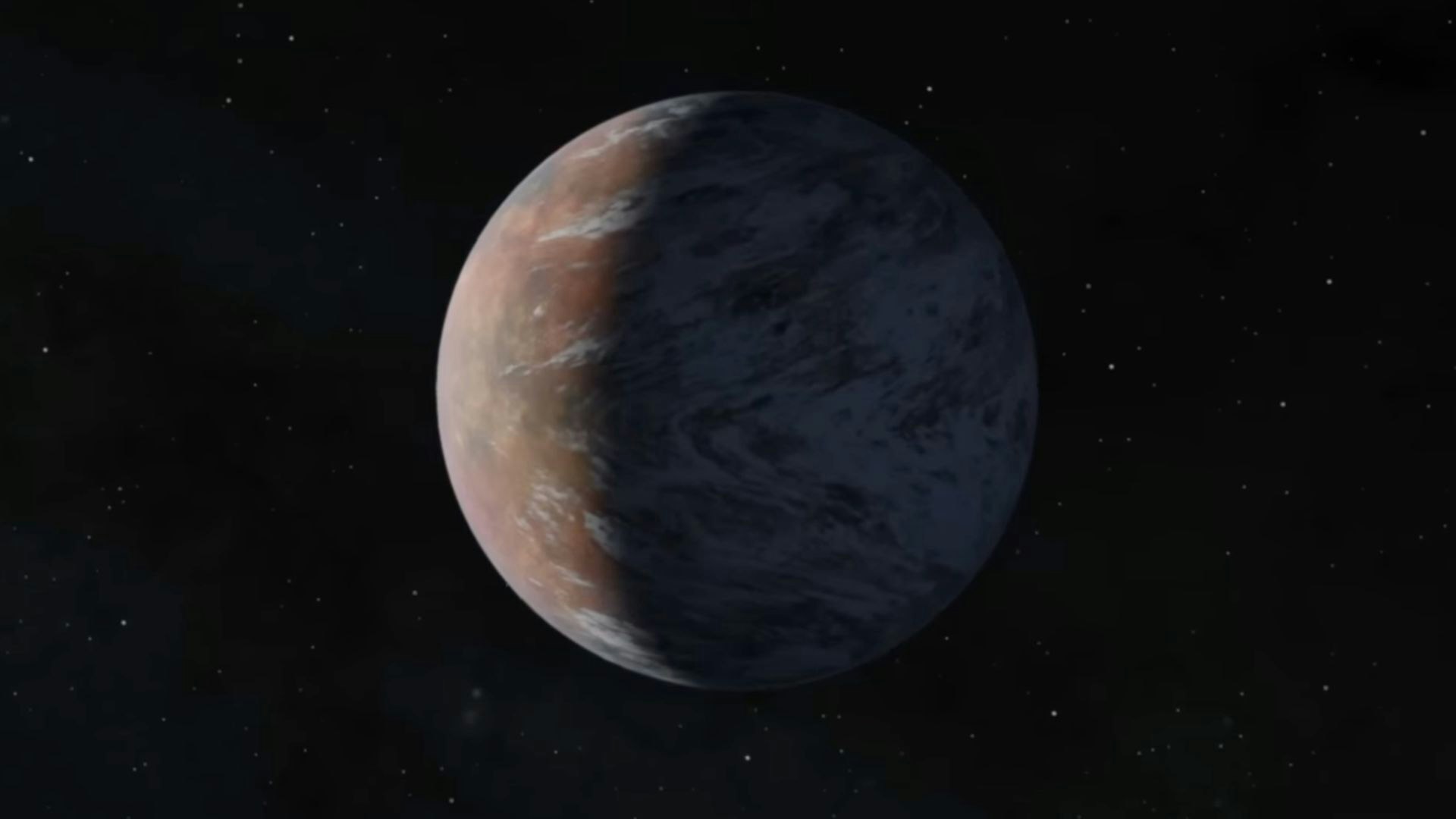

TOI 700 e

The planet was the fourth to be identified orbiting a star designated as TOI 700, a small, cool M dwarf star located around 100 light years away in the southern constellation Dorado.

It’s not visible in the Wyoming skies.

Three other planets in the system, which astronomers labeled TOI 700 b, c, and d, were discovered a year ago, also orbiting in the star’s “habitable zone,” which refers to the range of distances in which liquid water could be found on a planet’s surface.

“Sometimes we call it the Goldilocks Zone,” said Max Gilbraith, planetarium coordinator at the University of Wyoming. “So you can imagine for any star, if you’re too close, it’s too hot, and if you’re too far, it’s too cold.

“This planet should be at the right distance where liquid water would be present if there was water on the planet at all.”

Emily Gilbert, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, told Science Daily that “this is one of only a few systems with multiple, small, habitable-zone planets that we know of.”

TOI 700 e, along with its neighbors, may be what is known as “tidally locked,” with one side always facing the star (just as one side of the Moon is always facing Earth). It takes TOI 700 e 28 days to orbit its star.

TESS And The University of Wyoming

NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, nicknamed “TESS,” sent back the data that scientists used to identify the possibly habitable planet.

Launched in 2018, TESS monitors large sectors of the sky – more than 200,000 stars – for roughly 27 days at a time, allowing the satellite to track changes in a star’s brightness caused by a planet crossing in front of the star from our viewpoint.

The instrument on the satellite that measures the precise velocities at which stars move was designed and built by Pierce, a UW associate professor of physics and astronomy, at a lab in UW’s Physical Sciences Building.

In 2017, Pierce received a $175,000 grant from Indiana University to design and build the spectrometer, which also provides a detailed chemical composition of the stars.

“One of the cool things about the method that they detect these exoplanets with is that it gives us a very accurate read of the orbital period and distance of the planet,” said Gilbraith. “So as a result, we can also figure out its mass and radius – and putting all that together, we have a rough idea of what the planet might be like.”

Pierce’s colleague, Jang-Condell, would use the spectrograph to interpret data from the TESS satellite, thanks to a $750,000 grant from NASA’s Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research program.

“I’m going to be using it to measure the radial velocity of stars to confirm whether there are planets around them,” Jang-Condell said when she received the grant in December 2017.

UW Program

Gilbraith said that while the University of Wyoming has an impressive astronomy program, particularly with the ability to discover exoplanets (planets outside our solar system), the position of the telescopes at UW would not have been able to detect TOI 700 e.

“It is in the southern hemisphere, so we’re not going to be able to image it from here,” said Gilbraith. “But the Wyoming infrared observatory is a great instrument for detecting exactly the elements that are important to life, in atmospheres of planets like the one that was discovered.”

Gilbraith said UW operates the Wyoming Infrared Observatory, which can discern light that’s slightly more red than light that the human eye can detect.

“Those near infrared wavelengths are some of the most useful colors for detecting gases that are very important to life and star formation in the galaxy,” said Gilbraith. “Being high and dry in the Wyoming mountains, our observatory is able to peer through windows in the atmosphere to detect stuff like that.”

Gilbraith said UW students and faculty are always looking for exoplanets and studying them throughout their time at the university.

Not Going There Anytime Soon

Although the discovery of TOI 700 e is exciting, Gilbraith explained that humans won’t be visiting anytime soon.

“Going to any extra solar system would be a generations-long project, even optimistically,” he said.

Gilbraith pointed out that the Voyager probes, which have been in space for close to 50 years, are only just now starting to get past the orbital paths of comets.

“Those probes won’t reach the distance of the nearest star – which is Proxima Centauri, just three and a half light years away – until 40,000 years from now,” he said.