By Wendy Corr, Cowboy State Daily

wendy@cowboystatedaily.com

Across the arid scrubland of southern Wyoming, in seemingly random locations, is what remains of a network of large concrete arrows that point east.

In a wide, desert area just north of Green River and Little America off state Highway 41, one of these concrete arrows can be viewed in near-perfect condition; another is becoming increasingly surrounded by civilization just off Westedt Road in Cheyenne.

These, and 10 others scattered across the state, are remnants of what one expert called “the largest public works project that nobody’s ever heard of.”

These 70-foot arrows were part of an effort by the U.S. Department of Commerce to guide airmail pilots in the 1920s.

“Toward the end of World War 1, aircraft development had basically shifted almost entirely to Europe,” said David Marcum, a retired Airman from Cheyenne who has done extensive research on the country’s aviation history. “And so the United States government decided that they were going to jumpstart the aviation industry in this country by flying the mail.”

Transcontinental Airway

Marcum told Cowboy State Daily that in 1920, transcontinental air mail service began between New York City and San Francisco.

“The pilots flew a route that was called the transcontinental airway that took them through southern Wyoming,” he said.

Initially, the airway’s infrastructure consisted only of terminals that in the region were located at Omaha and North Platte, Nebraska, Cheyenne, Rawlins, Rock Springs and Salt Lake City. Planes and pilots were based at those terminals, planes were maintained and mail was transferred.

Marcum noted that airplanes back then didn’t have much in the way of navigation equipment.

“Terminals were linked by compass routes that, in theory, would guide pilots to their destinations,” he said. “In reality, compasses were very unreliable and pilots navigated by following both natural and manmade landmarks.”

One of the most visible landmarks was the transcontinental railroad tracks, which pilots called “the iron compass” and guided them over southern Wyoming.

But that strategy limited air mail pilots to flying just during the day, which didn’t take full advantage of what the planes could do.

Lighting The Airways

In 1924, Marcum said the U.S. Postal Service began constructing beacons that would be illuminated at night.

“The flattest part of the (national) airway was between Chicago and Cheyenne,” he said. “So, it made sense that that was the part of the airway that they’re going to fly at night.”

Marcum said that every 10 miles, rotating beacons were built on top of towers all along the air route between Chicago and Cheyenne. But every 3 miles, a system of acetylene-powered blinker beacons was set up.

Air Mail Takes Off

In 1926, the U.S. Department of Commerce was given jurisdiction over the airway through the passage of the Kelly Act, named for the congressman who sponsored the bill.

“It basically forced the post office out of air mail,” said Marcum. “The post office would still set rates, the post office would still actually deliver the mail, but private contractors would fly the mail – and the Department of Commerce was given responsibility for managing the airway.”

Boeing Air Transport was awarded the contract to carry mail between San Francisco and Chicago, while National Air Transport flew the mail between Chicago and New York City, Marcum explained.

“Then the Department of Commerce takes over management of the airway itself,” he said. “And it was the Department of Commerce that built the concrete arrows.”

Guiding The Way Over Wyoming

On May 20, 1926, the Air Commerce Act of 1926 was signed into law. That same year, the Aeronautics Branch of the DOC began rebuilding the Air Mail Service’s navigation system.

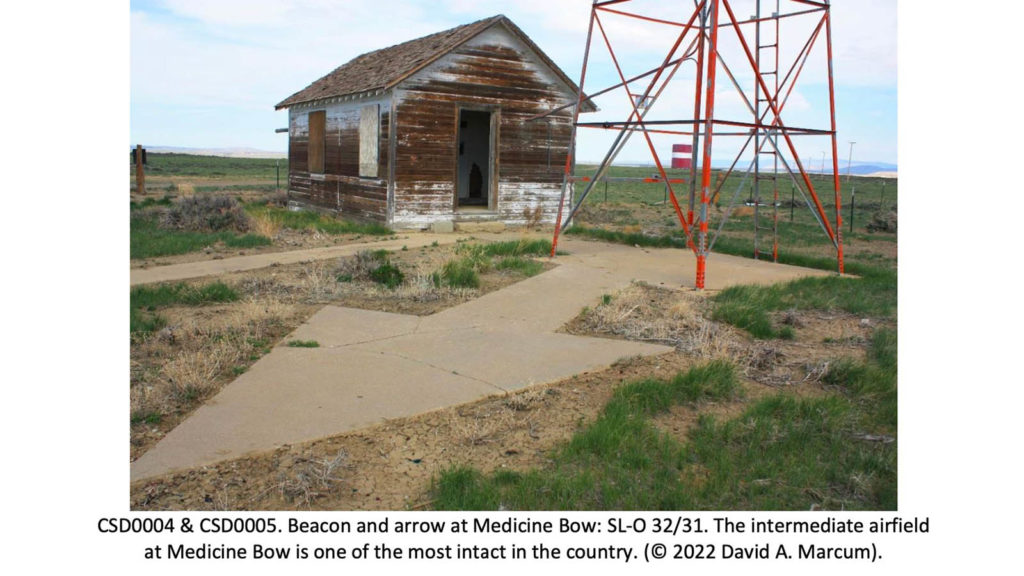

“Rotating beacons built on concrete directional arrows were erected every 10 miles along the route of the Transcontinental Airway,” said Marcum, adding that between Salt Lake City and Omaha, the arrows always pointed east.

Each beacon also was painted with an alpha-numeric designation.

“In Wyoming, they were numbered SL-O 38, etc.,” Marcum said, “with SL-O indicating that the beacon was on the Salt Lake to Omaha segment of the Airway.”

He explained that most of the beacons were powered by on-site generators since many were in remote areas.

“Some of them were actually built in close proximity to existing power lines, and so they got their electricity from the power lines – although some of them were actually powered by wind generators,” said Marcum.

Making Way for the Future

Radio aids eventually superseded the beacons because of the level of maintenance the visual aids required, said Marcum.

“Because beacons are a visual aid that can’t be seen when the weather is bad, the Aeronautics Branch also started developing the more capable system of radio aids to guide pilots,” he said. “If you’re driving around, you might see a strange-looking white structure out in somebody’s pasture. It kind of looks like it’s a small building, with maybe kind of like a funnel.”

Those are the radio beacons, Marcum explained, which themselves will be replaced by GPS.

“This is a continuing effort,” he said.

Preserving History

“There’s twelve arrows in the state that are relatively intact,” said Marcum. “And there are four that you can find bits and pieces of.”

Marcum said that landowners have been supportive of his efforts to document the remaining arrows and preserve what is left of this little-known piece of American history.

“These are going on 100 years old,” he said. “It took a tremendous amount of effort to erect this system and some of these sites are on private property. I would ask people to respect that fact.”

Two of the arrows can be found in a Google Maps search, Marcum said, adding that it’s worth the visit, even if the sites are in relatively remote areas.

“Out in Sweetwater County, the county and the BLM have actually done a good job of erecting signage and have done a good job of educating the public about the arrow out there,” Marcum said. “It’s a little bit harder to get to; it’s a dirt road so I would advise a high-clearance vehicle, but it’s an impressive arrow to visit.”

Marcum expressed his wish that the historic markers be treated with respect.

“I would ask people don’t vandalize the sites,” he said. “Visit them by all means, respect them, but leave them as you find them.”