It’s better to grow than to die, according to leaders of the historic mining town of Shoshoni.

Determined to attract businesses and younger families, Shoshoni is putting its own town hall up for sale in hopes of attracting a vibrant business that will create jobs.

The town has also purchased land to sell for housing and small ranches and has scheduled a major sewer system expansion, all part of an effort to keep the community from simply fading away.

Founded in 1905 as a mining town, Shoshoni’s population rises and falls with the mining and energy industries.

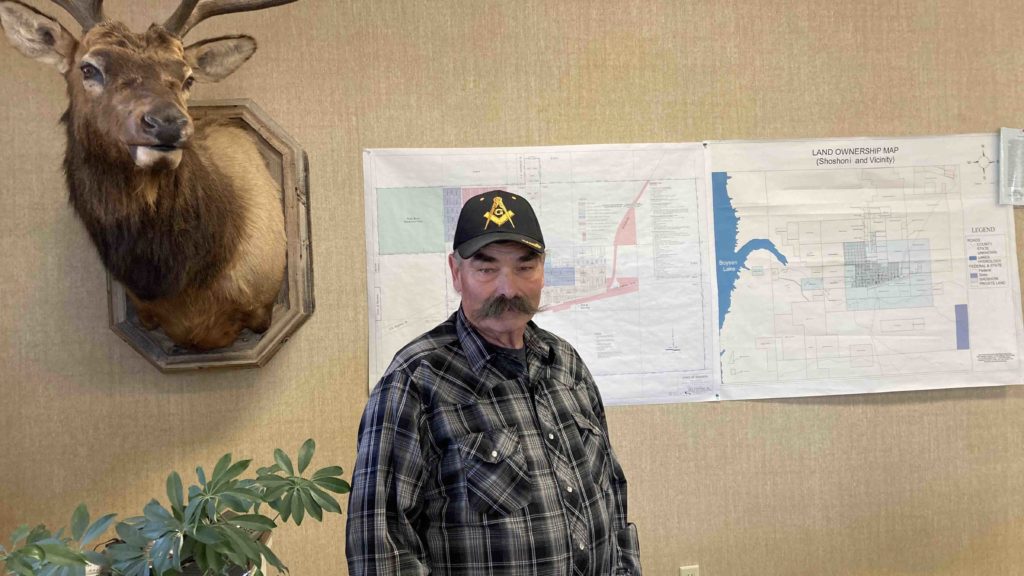

“There’s an acceptance of fate in a community when an industry goes away,” said Chris Konija, the town’s clerk and police chief. “People move out and the ones that do stay just accept the fate that’s coming; that there’s nothing they can do about it – and the town just dies.”

Konija said he has lived in many towns throughout Wyoming and has seen small towns sprout up and die off. But he hopes Shoshoni will be different.

And so far, it is. The train tracks still cross the town’s main road, U.S. Highway 20, and hikers still traverse its broad plains under the airy gaze of the Owl Creek Mountains.

There are more shuttered businesses than open ones: Shoshoni’s renowned malt shop, Yellowstone Drug, closed about 15 years ago when a buyer tried to move it to Casper. The Lip Rippers tackle shop shuttered roughly 10 years later. Many other small-town nooks have closed their doors since the 1970s uranium boom, when the town’s population peaked at around 1,000.

School of Choice

But even as townspeople packed up and left, Shoshoni secured one of the most inviting schools in the region.

The $49 million Shoshoni School opened in 2016, boasting a capacity of 500 students, although the town’s official population stands at 471.

About one-third of the school’s 380 students are from the nearby and much larger town of Riverton, said Shoshoni Mayor Joel Highsmith.

“Our school has a very good reputation,” the mayor said. “We have some really good teachers, our administration in our school is great – I can’t say enough good things.”

The school serves grades kindergarten through 12.

Shoshoni School also was less restrictive than its larger neighbors – but just slightly – during the COVID-19 masking and distancing policies of 2020 and 2021.

The school itself demands town growth, Highsmith said, as some prospective teachers have been thwarted by limited housing and infrastructure and have sought homes instead in Riverton, 22 miles to the southeast or in Thermopolis, about 32 miles north.

Sewer First, Homes Second

However, a town can’t grow without infrastructure.

The sewer expansion project on the town’s west side, scheduled for this autumn, should extend the town’s sewer system beyond its current limit. The project is now funded at about $1.65 million, paid for by a Wyoming Business Council grant with a 5% match from Shoshoni, aided by its largest business, Wyoming Mushrooms.

The new sewer system is being routed to serve the mushroom farm about 1 mile west of town, as well as the neighborhood and café its owners hope to build.

“They’re building some workforce housing on their property,” said Highsmith. “They’re also building a new restaurant there.”

The restaurant is envisioned as a greenhouse café: a glass oasis bursting with plant life on the windswept plains of Fremont County.

At least 70 new homes could benefit from the expanded sewer system as well that could be built on 113 acres of land the town purchased in December 2020. About 40 acres of the land is being developed into standard housing plats for 70 homes.

The additional acreage, Highsmith said, will be available for agricultural uses.

“We’d allow people to have wildlife, 4-H projects, horses – that sort of thing,” he said.

Highsmith noted that young families favoring rural small towns often prefer animal-friendly zoning.

Shoshoni budgeted for that parcel and paid cash for it, said Highsmith, who sees the project as a chance to offer affordable housing during a real estate boom that has sent prices in larger surrounding towns skyrocketing.

City Hall

Shoshoni has placed its town hall up for sale, but not just to the highest bidder.

“Economic development is the driving force,” said Highsmith, noting that the Town Hall building on Second Street – which morphs into Highway 20 as it arcs out of town – is in a noticeable and high-traffic area that many businesses would envy.

“It’s not necessarily the highest bidder” that will win the property, the mayor continued, adding that a business creating about 20 jobs would be more likely to get the building than one offering just three jobs, for example.

“We could very well select the lower cash offer – if (the business) is better for the town of Shoshoni,” he said.

The Trees Grew Over The Top

Born and raised in Shoshoni, Monica Gabriel – known locally by her maiden name of Monica Nuñez – remembers the 1970s and 80s version of her town as “really fun,” but just a touch wild because of its Western oil-worker culture.

“When I was a kid this was a really fun town,” said Nuñez. “And it was pretty. When you pulled into town onto Second Street, the trees grew over the top; they were green and leafy.”

Nuñez recalled the idyllic American childhood of setting off at daybreak on a bicycle and ambling home just before the streetlights switched on for the night.

“There were always things going on: bonfires, street dances, fireman’s auctions, barbecuing in the park,” she said. “For a number of years, there hasn’t been (that activity), and everything has left now.

“But our mayor, our town council, our chief of police… they care about Shoshoni as much as most of us do,” continued Nuñez. “And they’re doing everything they can to make it better.”

Crossroads of Wyoming

Highsmith calls Shoshoni the “Crossroads of Wyoming,” because despite its meager population, the town, which hugs a major highway intersection, sees more than 1 million people passing through each year, according to Wyoming Department of Transportation monitoring.

Highsmith is arranging a feasibility study to determine if Shoshoni should build a motel to accommodate the visitors who may want to get off of the road for a break.

The town also purchased the defunct property of the former Shoshoni Motel, along with the vacant Lip Rippers tackle shop, with the intention of tearing both buildings down to build workforce housing.

That housing, said Highsmith, may become the home to a likely influx of workers expected to take up jobs at the busy crossroads gas station, Fastlane, after it finishes building an 8,000-square foot travel plaza in the coming months.

“They’re going to need employees,” said Highsmith. “They’re short-staffed right now – and there’s not a single rental available in Shoshoni.” Nuñez, who is the business administrator at Fastlane, said efforts to build the travel plaza were launched by the station’s owner, Tim Davis, about a year ago.

Nuñez praised Davis’ decision repeatedly.

Fastlane bought an entire block just west of its current facility to expand its gas pump count from four to 14 and to open another convenience store with food service.

“They started the groundwork yesterday; actually moving dirt,” Nuñez told Cowboy State Daily on Tuesday. She said building supplies shortages have produced a “struggle,” but “the whole world right now is struggling with that.”

Town ‘Doesn’t Have To’ Die

Konija said that despite Shoshoni’s boom-and-bust history, it can persevere if its residents are quick to identify growth opportunities.

“It doesn’t have to (die off), if you just rethink your approach and capitalize on what is there, available, and use that for leveraging into action other facets of the community,” he said

Konija and Highsmith both said that, as with any major decision, there are dissenters.

Highsmith said some of the townspeople are concerned that renovations will boost their property values, and thus their assessed taxes up. He also said a town-wide movement of aesthetic improvements is unwelcome to people who moved to Shoshoni specifically to “keep all (their) junk.”

“You get a lot of pushback,” said Konija. “’It’s just hopes and dreams,’ we’ve been told.”

But he noted adding a better infrastructure and business foundation is the first step in what could be a years- or decades-long pattern of “slow, managed growth.”

Konija said Shoshoni, like so many small towns in Wyoming, is worth saving because the people embody “self-sufficiency – and taking care of their own.”