Guy Edwards cradled the sheep’s head between his arms on the wooden platform as he ran the clippers under its chin. When the sheep kicked, Edwards stilled it with his legs and continued shearing under the bright spotlight in the otherwise dim barn as a row of teens looked on.

It’s physical work and tomorrow, Edwards will be sore. Today, however, he’s in his element as the clippers hum on either side of him and the sheep bleat their chorus of discontent as they wait in line in the chute behind him.

A few clipper strokes later and Edwards pushed the fully intact fleece into a basket as the pink-skinned sheep jumped to its feet, scrambling off the platform into the dirt pen where it looked briefly over its shoulder as if wondering what the heck just happened before wandering off to join the others in the corral.

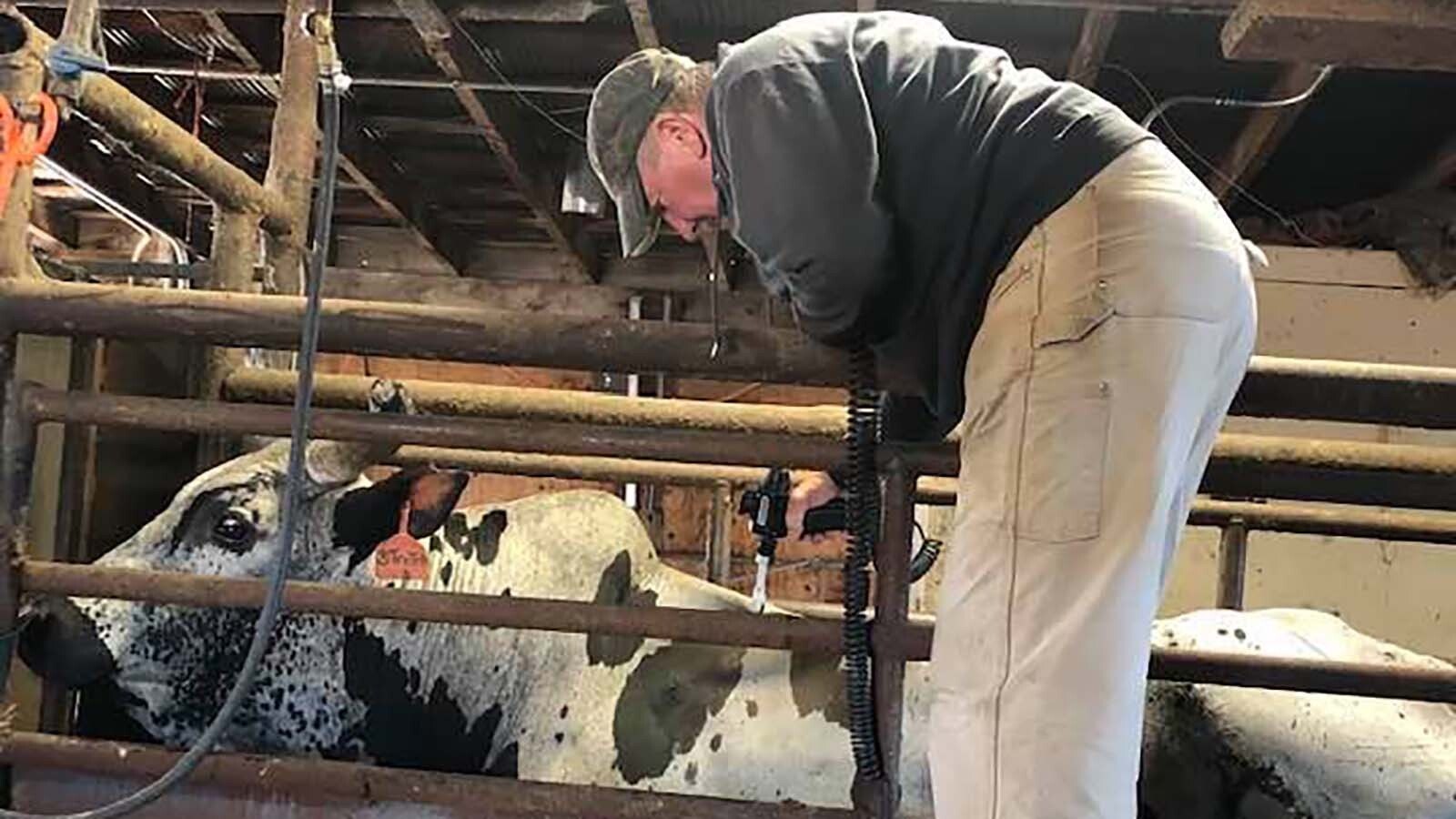

Saturday morning was day two for 25 teenage students from around the state and Montana who signed up to attend a sheep shearing school hosted by Edwards on his family’s ranch in south Campbell County. The Edwards family has a herd of more than 250 sheep, including South African Meat Merino (SAMM), Rambouillets and a hodgepodge of mixed breeds.

Edwards, now 40, took his first shearing class, taught by one of his neighbors, at about the age of 14. Right out of high school, he joined a seven-man crew and traveled the country shearing, as well as taking part in a three-month trip to England.

Shearing is hard work and a lot of time and practice are needed to get good at it, Edwards said.

Despite its laborious nature, he loves the work.

Dying Breed Of Sheep Shearers

He’s part of hat he calls the dying breed of sheep shearers, which is why he offered up his flock for the class when asked by Ronda Boller.

Boller, who is also a rancher and whose family had sheep when she was growing up, said she got the idea for hosting a shearing class after hearing several areas sheep producers complaining about how hard it was to hire shearing crews during the pandemic. Most of the crews come from Australia and New Zealand and the long quarantine times and travel restrictions made it unprofitable for those crews to come to the United States.

Boller worked with county and state wool grower auxiliaries to get $2,000 in grant money to hire Edwards’ friend and fellow sheep shearing teacher Wade Kopren, who drove his portable shearing school and equipment over from his home in South Dakota. Unlike other shearing schools that can cost upward of $450 per student for a weekend class, students attended the weekend session free of charge.

Nobody made money from the event – which to Boller’s knowledge may be the first of its kind in the state and the first in Campbell County in two decades. The teachers were there because of their love of the industry and to pass on knowledge, Boller said, including Kopren who also brought two volunteer instructors with him.

Kopren admitted he was having fun at the class and was glad to pass his knowledge along to help teach the next generation these vital skills.

“No George Jetson Machine”

“There’s no easy way to do this,” Boller said. “There’s no George Jetson machine to just run them through. It’s hard work, and most young people don’t want to do it anymore.”

For Kopren, it was something he always loved to do. He got an early start in shearing. While in high school, he joined a crew and spent 25 years working professionally. He started his own crew in 2002, and then ran five crews across six states including North and South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, Idaho and Minnesota, shearing more than 350,000 head each year.

He’s since retired and now just teaches shearing schools, but like Edwards, he loves the art of shearing which he calls “poetry in motion.”

This is what he and Edwards are trying to teach the students, reaching out to a whole new generation of ag producers who seem genuinely curious and interested in learning the craft.

“I want to teach a dying industry to the next generation,” Edwards said. “There’s such a shortage of sheep shearers.”

For some ranchers, this has meant selling off their sheep because they can’t find anyone to shear their sheep once a year and it’s become more hassle than it’s worth, Edwards said.

However, sheep and wool prices continue to rise, with wool netting about $2.30 a pound in the grease, compared to less $1 about two years ago. That’s an incentive for small producers to get trained to be able to handle their herds.

“Prices are way up,” Anna, Guy’s wife said. “It’s definitely a seller’s market.”

New Generation of Shearers

In years past, the younger generations didn’t show much of an interest in shearing because it’s such hard and dirty work, Kopren said, but that seems to be shifting if today’s students are any indication.

Edwards’ son, 14-year-old Tucker, is on his eighth sheep today. He’s learning the skill of positioning the sheep that his teachers have been stressing all day. Along with positioning the animal, you have to be careful to pull the skin taut so there are no wrinkles and learn to use your legs and body to keep the sheep comfortable and still.

‘It’s really tiring,” Tucker said.

His dad laughed that he feels the worst on the day he shears and the best day of his life the day following because it stretches out every muscle in his body.

Maggie Urbigkit is also enjoying her first go at shearing. The 28-year-old drove over to Gillette from Pinedale, where she lives on her husband’s family’s ranch.

She’s fairly new to ranching and is here today to learn as much as she can to “step up her game.”

“I came here just to get a better understanding of how to shear sheep,” she said. “I’m married into this industry, and so I want to gain as much knowledge as I can and play catch up.”

It’s more physical than she imagined and requires a lot of legwork, which has given her a new appreciation for those who do the work regularly.

She’s also sheared about eight sheep at this point and said it’s going really well.

“I think all these instructors are so great and helpful,” she said. “I’ve learned so much already, and it’s been a really fun and a pretty relaxing environment.”

Cheap Way to Travel the World and Meet Women

Australian native and veteran sheep shearer Ashley Fuller drove over from Casper to help Kopren teach class.

The two had worked together for years before Fuller retired from the industry.

They talk about shearing as an art form, where the real work is done by the hand that’s not holding the clipper but instead is moving the sheep constantly in a rhythm distinctly its own.

Both are well known in their field, and at the top of their game, could shear upward of 200 sheep a day while striving every time to get just a bit better at their craft.

“There’s no end to it,” Fuller said, “there’s always one little thing more you can improve every time. That’s what makes it so fun.”

And as they both learned, it was a great way to travel the world and make money while also meeting women. Both met their wives on the job, which also impressed upon them the need to have manners and be polite, a lesson they are adamant about today while working with these students.

“Work ethics, manner and respect are paramount in life and work,” Kopren said. “You want to be washed up and polite when working with customers. Take the extra step and show them respect. It makes a big difference.”

Kopren said he was pleased to see younger people expressing interest in what he still believes is a great job, particularly with the rise in smaller producers offering opportunities for shearers to procure work while helping with small family herds.

Isaac Rojo, a 14-year-old from Sheridan, came to class because he said he wanted to learn how to shear so he can help out his family.

“It’s pretty physical,” he said, “but I like it.”