By Chris Navarro, guest columnist

It was August 17, 1997. I had flown my son JC to compete in a Wyoming Junior Rodeo in Rock Springs, Wyoming.

The rodeo was over and we were getting back to the airport just at sunset. I had checked the weather and noticed a thunderstorm coming in from the southwest about 30 miles out.

I did a quick preflight of my plane — a 1959 Cessna 182 Skylane. We jumped in and took off and were heading northeast back to Casper, a distance by air of 170 miles.

My plane would do about a 150 mph. I was in front of the storm and would make it to Casper in an hour and 15 minutes.

As my plane left the end of the runway, I noticed the sun was setting and it was starting to get dark. I was climbing out to 9,500 feet. Fifteen minutes into the flight, I was in total darkness.

I was starting to get worried when I realized it was a moonless night with heavy clouds and I was flying over the Red Desert and there were no lights or landmarks.

I was really scared now because it was total black outside. I could not see the ground and the windshield visibility was zero. I was in big trouble as I had just flown into hard IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) conditions.

I was a VFR (Visual Flight Rules) pilot in a VFR rated airplane and just made a life-threatening critical mistake.

I looked over at my young son who was in the seat next to me already taking a snooze. I could feel my heart beating when I realized not only had I endangered my own life but that of my young son.

I could feel the panic starting to rise in me as my adrenaline started to pump through my body. I started getting mad at myself. “How could I be such a dumb ass for getting into this jam,” I thought.

But my next thought was to relax, stay calm, and work the problem: You have to get out of this, use your head!” I told myself.

I had been flying for a few years and had over 300 hours with only five hours of hood-time and maybe 12 hours of night flying.

I was not instrument-rated but I was a member of the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association.

I always read their magazine reports and remember the story that determined the average VFR pilot had “178 seconds to live” upon entering “Instrument Meteorological Conditions.”

Because the pilots would become disoriented with vertigo and start chasing their instruments, they would over-correct the plane into a spin. It is a dangerous situation.

American research showed that 76% of VFR into IFR or IMC (Instrument Meteorological Conditions) accidents involve a fatality. This is exactly what killed John Kennedy Jr., his wife, and sister in-law.

Relax, be calm, don’t make any quick movements. Just watch and concentrate on your instruments.

Just keep the wings level and straight. I started holding the yoke which controls the alerions of the plane with just my left index finger and thumb with the lightest of touch.

I next decided I would only turn the plane using a 100% rudder to stay on my heading and for holding my altitude and elevation, I would use only the trim wheel.

That is all I was going to think about and that’s what I did for the next longest 30 anxiety-filled minutes of my life. I kept flying like that until I saw the lights of Casper.

I was never so happy and relieved as I was when I saw the city lights and the Casper Airport runway. We had a smooth landing, my son woke up, and we pushed the plane in the hanger.

My son never knew how close we had come to having a disastrous night. I promised myself I would never make that mistake again and I never did.

I grew up in a family of aviators. My father and three older brothers were all military aviators and I soloed my first plane when I was 19 years old.

I remember my oldest brother Rick, who was a Navy pilot and later a Delta Captain, telling me when I started flying that flying won’t kill you, it’s the decisions you make when flying that will.

True words brother.

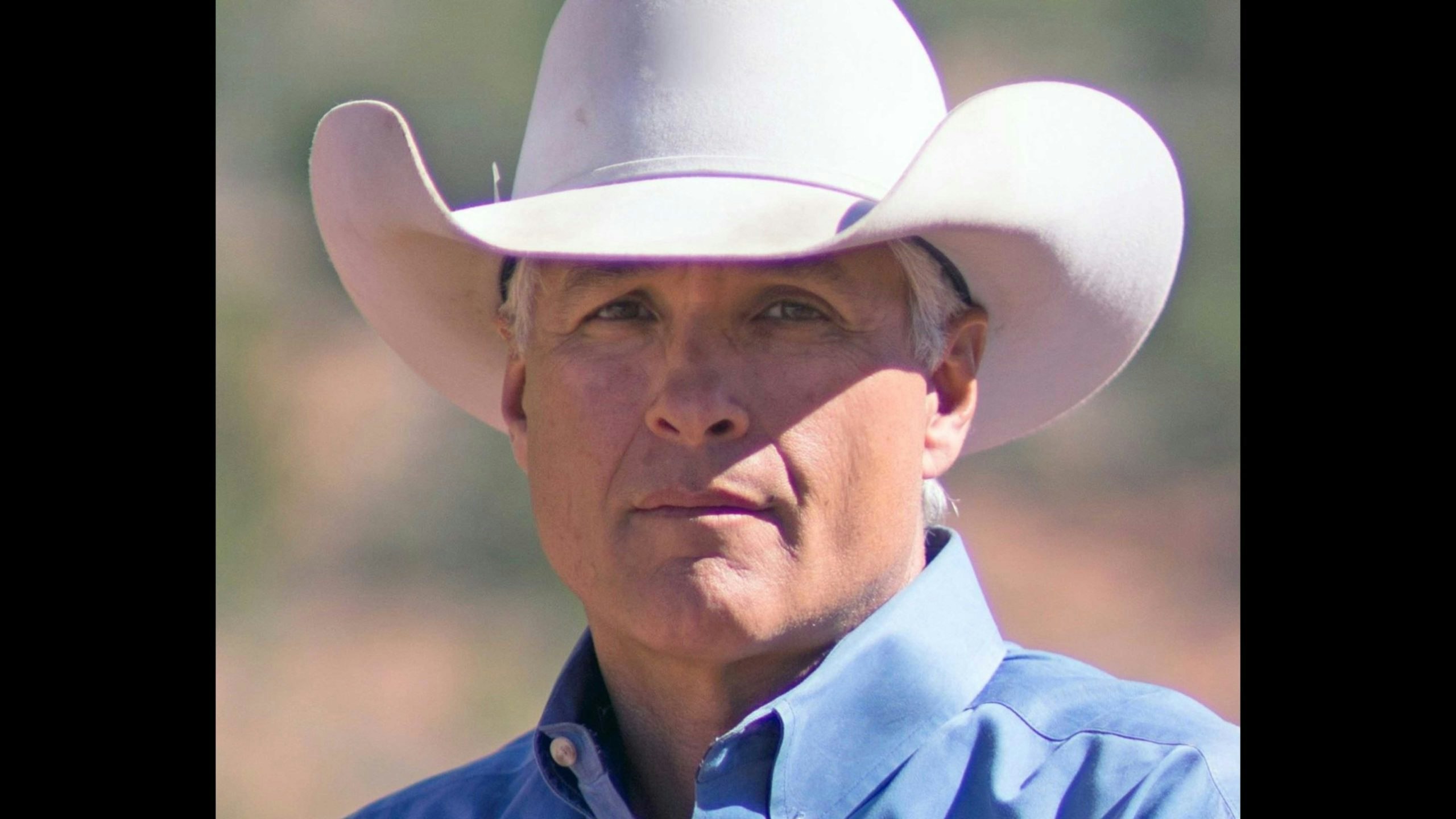

National award-winning artist Chris Navarro from Casper, WY has been sculpting professionally since 1986. He is best known for his large public sculptures and has over 35 monumental bronze sculptures placed throughout the country including a 16-foot-tall Bronze of the famous bucking horse Steamboat for the University of Wyoming. Navarro received the Legacy Award and induction into the Bull Riding Hall of Fame 2021.