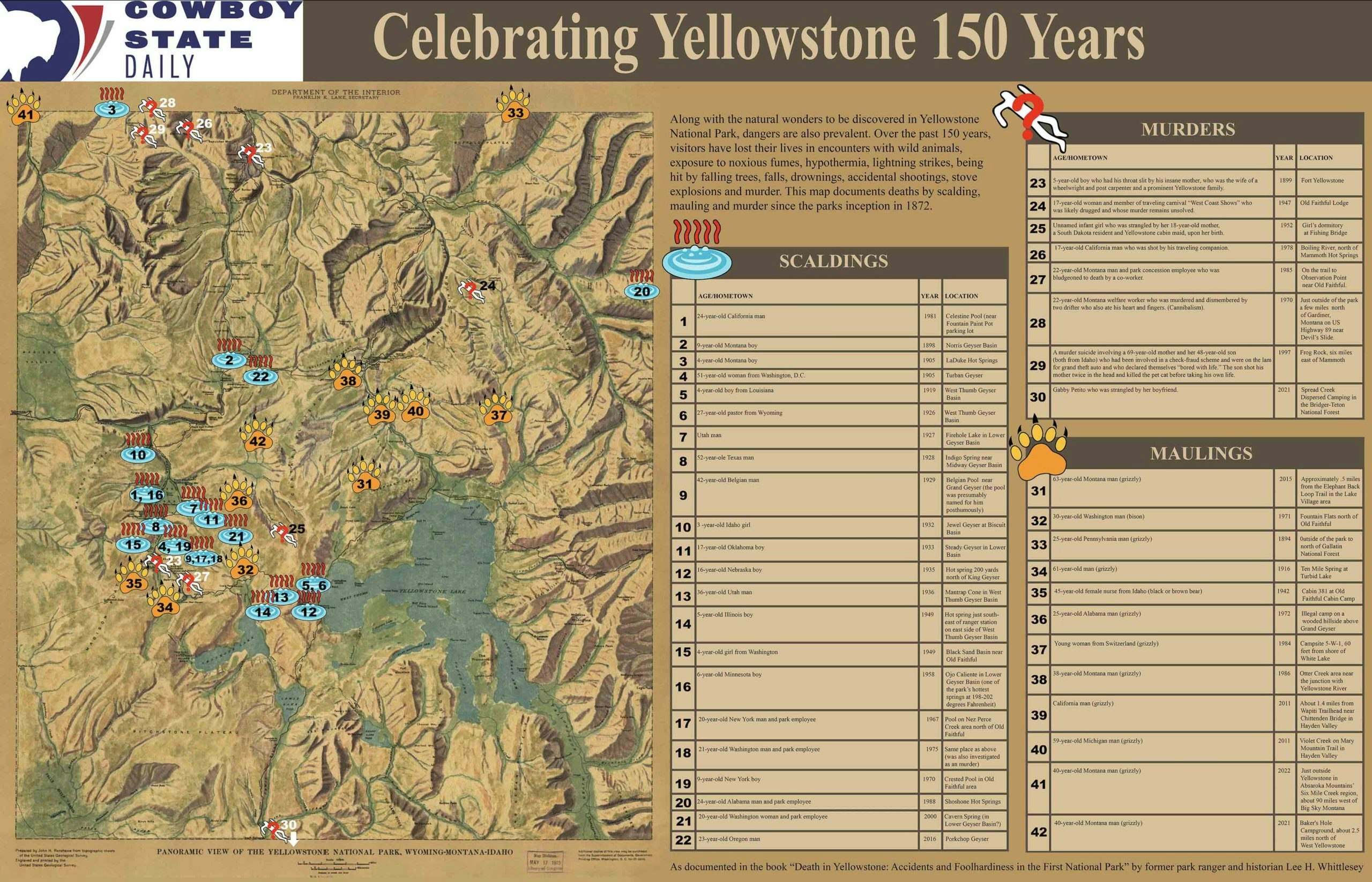

Just in time for Yellowstone’s 150th anniversary, download your map of “Scaldings, Maulings, and Murders” exclusively from Cowboy State Daily.

Onlookers no doubt watched in horror in July 1981 as 24-year-old David Kirwan dove headfirst into the boiling Celestine Pool at Yellowstone in July 1981.

Kirwan had been chasing after his friend’s Great Dane Moosie, who had escaped from the back of the pickup truck and jumped into the scalding hot spring estimated to be about 200 degrees Fahrenheit.

It didn’t take long for Kirwan to realize his mistake. Within seconds, he popped out of the boiling water and attempted to pull the dog to shore. Kirwan made it; the dog didn’t.

Kirwan’s friend received third-degree burns on his feet as he helped pull Kirwan’s badly burned body onto the rock shelf. Kirwan managed to stand up before staggering backward. His buddy and another onlooker led him toward the parking lot for help.

“That was stupid. How bad am I?” Kirwan reportedly asked his friend as he stumbled onto the boardwalk.

Kirwan’s eyes were totally white, as if blind, and his badly burned skin had already began peeling off. When another man on the scene ran over and tried to remove one of Kirwan’s shoes, his skin started to flay off. Later, rangers found two large pieces of skin shaped like human hands next to the spring.

With third-degree burns covering his entire body, emergency responders took Kirwan to the clinic at Old Faithful, where he was treated by a burn specialist who could do nothing at that point except numb the pain. Kirwan died at a Salt Lake City hospital the following morning.

Moosie never made it out. His body was not recovered, though oils from his body caused small eruptions in the water in the day following.

No Amusement Park

Kirwan’s is one of the more than 20 deaths that resulted from tourists either falling or willingly jumping into Yellowstone hot springs as documented in the book, “Death in Yellowstone: Accidents and Foolhardiness in the First National Park” by attorney and longtime Yellowstone tour guide, park ranger and historian Lee H. Whittlesey.

Whittlesey’s book catalogs deaths and accidents brought on by reckless tourists in the park from its founding in 1872 to 2013.

Along with drownings and scalding deaths, Whittlesey dug into the various ways tourists at the park have died or were seriously injured as a result of their own foolhardiness.

Turns out, there are many ways to die in Yellowstone, including encounters with wild animals, exposure to noxious fumes, hypothermia, lightening strikes, being hit by falling trees, falls, drownings, accidental shootings, stove explosions and murder.

Because this information was not readily available from the park, Whittlesey gathered his data by poring over park superintendent records and local news reports.

Most of the events, as Whittlesey noted, stemmed from the visitors’ false sense of security that they are in a managed area where the animals are tame, much like an amusement or city park. As he delved further into the nature of these deaths and accidents, he determined that many were man-caused, the result of hubris or carelessness about the park’s imminent dangers.

When asked in a 2021 interview published on the park’s website why he was drawn to write about “such a morbid subject,” Whittlesey responded that someone needed to do it.

He referenced an earlier conversation with fellow park employees.

“We were talking about what books were important for tour guiding, and somebody suggested, ‘I know the book that ought to be written – a book about the ways people get themselves killed in the park,’” Whittlesey told the reporter.

As soon as his colleague broached that idea, Whittlesey said he saw the chapters beginning to unroll in front of his eyes.

From the perspective of a both a lawyer and a park ranger, he considered the book a way to legally protect the park while also alerting tourists to the many hidden and obvious dangers that one might run into while exploring the park.

At many points in the book, Whittlesey warned his readers that Yellowstone is not an amusement park full of tame animals and guardrails on the trails. It’s a place full of hidden and obvious dangers, he said, which is why he felt compelled to share his cautionary tale while also capturing the park’s colorful history.

When asked by the reporter what scared him the most, Whittlsey said falling off a cliff or running into a bison.

Fifth Most Dangerous Park

Comparatively speaking, a visitor is less likely to die in Yellowstone than in other national parks.

According to a 2022 survey by Outforia, a nature and outdoor resource, the Grand Canyon is the most dangerous park with 134 documented deaths, according to records obtained by the outlet. The survey does not specify when the deaths occurred.

The second most dangerous park was Yosemite with 126 deaths, followed by 92 people dying in the Great Smoky Mountains. Down the list at number five is Yellowstone with 52 out of a total of 4 million annual visitors.

The most common cause of death in Yellowstone, according to the survey of both natural and unnatural causes, is a tie at 12 apiece for motor vehicle crashes and heart attacks. The second most common cause of death, per the survey, is a tie between falling and undetermined causes resulting in seven deaths each. Drownings have resulted in five known deaths in the park.

Looking at all national parks, the survey indicated that falls were by far the most common way to die, accounting for a total of 245 deaths. Medical and natural causes came in second with 192 total deaths with undetermined causes resulting in 166 additional deaths.

Siren Call Of The Beautiful Blue-Green Hues

To his surprise, Whittlesey discovered death by drownings or being boiled to death in one of the park’s 10,000 springs, geysers, mudpots and steam vents — with temperatures reaching up to 205 degrees Fahrenheit — posed a far graver threat than being mauled by a wild animal.

The beautiful blue-green hues of the geyers and spring seem to attract people to their edges, he found, with the earliest thermal injury dating back to 1871 when Truman Everts, a member of the 1870 Washburn Expedition, decided to take a soak after being separated from his group and being lost for 37 days.

As the number of visitors to the park increased in the 1880s, so too did hot springs-related injuries involving both tourists and park employees.

One of the worst reported incidents documented in Whittlesey’s book involved four Chinese laundrymen who were thrown in the air and scaled to death after a geyser erupted one night. The author acknowledged the various holes in the story, which nonetheless was picked up by national media outlets. The National Enquirer trumpeted the garish details with its title “Boiled Chinamen in the Yellowstone Park Region,” featuring a large woodcut drawing of bodies, pigtails and washtubs being spouted into the air.

The most recent death was in 2016 when a 23-year-old man from Portland, Oregon, slipped and fell into a hot spring near Porkchop Geyser, according to a 2021 article by Tom Arrandale.

Along with the fatalities, many people have suffered severe burns, Arrandale noted, with 16 park guests burned extensively enough during the 1990s to warrant hospital treatment.

Hank Heasler, principal geologist for the park, said that despite the numerous warnings, posts and signs, rangers end up rescuing one or two visitors – frequently children – from geothermal features each year.

“Geothermal attractions are one of the most dangerous natural features in Yellowstone, but I don’t sense that awareness in either visitors or employees,” Heasler said.

It’s difficult to document exactly how many incidents have happened because such information is not easily obtained.

When asked to quantify the injuries and deaths that have occurred in the park, Linda Veress, director of strategic communications for the office of the park’s superintendent, referred Cowboy State Daily to hundreds of press releases issued on the park’s website.

The most recent scalding event identified by Cowboy State Daily occurred in September 2021, when a 19-year-old teen from Rhode Island jumped off of a boardwalk to save her dog, which wandered into the scalding hydrothermal pits at Old Faithful. The teen escaped with only second- and third-degree burns on 5% of her body and returned home after a few months at a burn center in Idaho.

It should be noted that it’s a federal crime to leave the park’s boardwalks, swim in the hot springs or willingly approach wild animals or violate any of a host of other commonsense rules. But the threat of federal prosecution doesn’t deter visitors from taking part in such behavior.

Yellowstone has exclusive jurisdiction and crimes committed in the park are federal offenses, Veress said, with misdemeanor offenses typically carrying a penalty of up to a $5,000 fine and/or up to six months in jail.

Such was the case for 37-year-old Aaron Merritt from Maine who pleaded guilty for making mad dash across the thermal areas to Old Faithful in July 2021 while wearing a raccoon hat and waving an American flag. For his stunt, Merritt was sentenced to 15 days in jail, fined $200 and permanently banned from future visits to the park.

Fluffy Critters

Whittlesey was surprised to learn that scaldings posed far more danger in the park than maulings by wild animals.

As of 2013, Whittlesey counted two deaths from bison and seven from bears. He also found that visitors seemed to be far more attracted to the 2,000-plus pound bison due to its status as a legendary symbol of the American West.

Injuries caused by wild animals are far more common than deaths. An undated release from Yellowstone said that since 1979, 44 people had been injured by grizzly bears with an average of one per year reported during the 1930s through the 1950s. In other words, one out of 2.7 million visitors is at risk of being mauled.

The odds have gotten worse over time, however. In the 1960s, the mauling figure leapt up to four per year, only to drop to one injury every two years during the 1970s and only two total attacks throughout the 1980s.

The most recent death blamed on a grizzly bear occurred in August 2015, when a hiker was killed by an adult female grizzly bear near Elephant Back Loop Trail in the Lake Village.

To this day, relatively speaking, very few visitors are likely to die by bear or bison attacks.

In total, park officials counted eight bear deaths in the park between 1872 and 2015. By contrast, during the same period, 121 people died in drowning incidents, 21 from burns incurred after falling into hot springs and 26 by suicide.

“To put it in perspective, the probability of being killed by a bear in the park is only slightly higher than the probability of being killed by a falling tree (seven incidents), in an avalanche (six incidents) or being struck by lightning (five incidents),” YNP officials said.

Visitors nonetheless continue to take their chances approaching wild animals with many injuries documented over the years.

Taming The Beast

The earliest death caused by a bison was recorded in 1902, as reported in Whittlesey’s book, and involved 49-year-old Dick Rock, who was a reportedly a well-known poacher in the area.

Rock, in fact, was killed by one of the bison he stole when he was showing his friend how “tame” the animal had become. Despite warnings from his friends and others that the animals would one day kill him, Rock was nonchalantly feeding the bison when one became enraged and charged him, pinning his body against the corral. The bison then repeatedly pitched Rock in the air like a toy, goring his body every time he hit the ground.

In the end, the massive animal managed to rip off all the man’s clothing and leave 29 horn holes in him.

According to a bystander, Rock managed to get out of the coral before “his eyelids twitched a time or two and he was gone.”

Prior to the 1990s, bison injuries were fairly rampant in the park with about 46 non-fatal gorings reported between 1983 and 1994, according to Whittlesey’s research. Part of his job at the park involved monitoring traffic jams caused by bison herds and making sure visitors kept their distance.

People can’t seem to stay away from the massive bison, with an average of up to five bison encounters per year reported between 1995 and 2012.

One of the more memorable encounters recalled by the author included a 70-year-old man from New Jersey who was tossed 15 feet in the air by a bison before the animal ripped his leg open with its horn.

Every year, there seem to be run-ins with a bison, including a 72-year-old California woman who in 2020 ignored the 25-yard safety barrier and instead got within 10 feet of a bison to take its picture before the animal gored her.

In 2018, another California woman, 59-year-old Kim Hancock, was gored by a bull bison crossing a boardwalk when she stepped closer to get a look. A second woman, 72-year-old Virginia Junk of Idaho, suffered minor injuries when she was butted in the thigh, pushed and tossed off a trail after accidentally getting too close to a bison.

In 2015, five people were injured by bison.

Brushes with elk are another hazard, though far less common than encounters with bears and bison.

A 53-year-old Texas woman was attacked in June 2018 by a cow elk who she surprised as it bedded down with its calf near the woman’s cabin. The woman attempted to quietly back away when the elk charged her, kicking her in the head and torso.

Less common are coyote attacks, though a skier was bitten by one in 2020 while cross-country skiing.

Murders In The Park

More infamous are those who have been murdered in the park. According to Whittlesey’s reporting, eight people have been murdered in Yellowstone Park. At least 13 others murders have occurred on the nearby Montana towns of Cooke City, Gardiner, Aldridge, Jardine and Horr.

Park spokeswoman Veress said she does not recall anyone being murdered in the park since 2014.

The murder numbers do not include the dozens of people who get lost and perish as well as those who specifically enter the park for the purpose of taking their own lives.

One of the most gruesome deaths in the park recounted by Whittlesey was a murder in 1889 involving George Trischman, his wife Margaret and their four children.

Margaret, who was known to suffer from mental health issues, slashed her own throat in an attempt to take her life. Later, Margaret tried to say that she had been assaulted by a large man, which didn’t hold water with authorities. In the end, she was committed to a mental hospital in Warm Springs, Montana.

When she returned to the family’s home in Mammoth a few months later, Margaret slashed the throat of her youngest son, nearly severing his head from his body, before chasing the other children with her hunting knife. She was ultimately found to be clinically insane, jumping into the Yellowstone River from the train that was taking her to the hospital in Washington, D.C. Her body was never found.

More recent is the brutal murder in 1970 of a Montana welfare worker just outside the park in Gardiner, Montana, off U.S. Highway 89 near Devil’s Slide.

Twenty-two-year-old James Michael Schlosser had the grave misfortune of picking up two hitchhikers outside of the park. Unknown to Schlosser, the two men – Stanley Dean Maker and Harry Allen Stroup from Sheridan – were high on LSD. Baker, who would later admit to cannibalism, Satanism and other occult practices, referred to himself as “Jesus.” Stroup appeared to just be along for the ride.

According to the Whittlesey’s book, Schlosser drove the men toward the park’s northern entrance, but the three were told campgrounds were full, so they ended up camping at a site outside Gardiner.

While Schlosser was asleep, Baker shot him in the head, then dragged his body to the river, where he proceeded to cut it into six parts with his knife. He took care to cut off several of Schlosser’s fingers and also beheaded the corpse, cutting out his heart and eating it.

The two men then stole Schlosser’s car but were eventually nabbed by police in California after being involved in a hit-and-run accident.

When apprehended by the highway patrol trooper, Baker reportedly told the officer, “I have a problem; I’m a cannibal.”

When officers searched the men, they found the remains of finger bones in both of their pockets.

These tales, as the author repeatedly noted, are meant as cautionary tales for what might happen if a person is careless or lets their guard down.

In the end, Whittlesey said he’s not trying to terrify anybody but rather be realistic about the potential threats, which of course, is part of the what draws so many visitors to the iconic park.

“That’s part of the charm, the adventure, the fun,” he said in the 2021 interview with the Yellowstone reporter. “In my opinion, if you cannot get killed and eaten by a wild animal, then you don’t have a true wilderness area.”