By Clair McFarland, Cowboy State Daily

“The greater the evil, the greater the hero.”

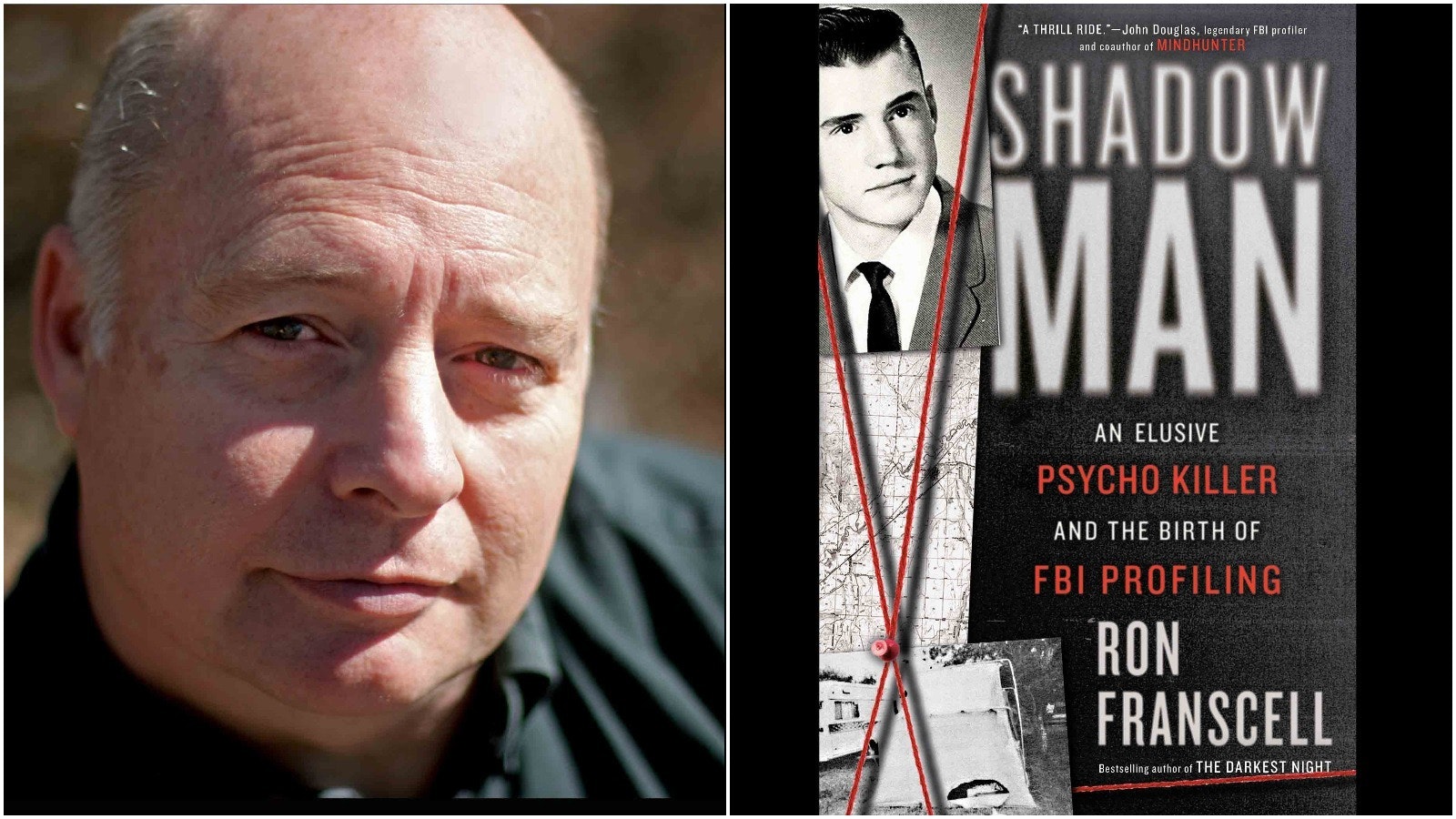

That’s what Wyoming-raised author Ron Franscell thought as he undertook the two-year research and writing project that would become his latest book, “ShadowMan,” which hit online and market shelves Tuesday.

The nonfiction story, told in the literary narrative device known as “true crime,” traces a 1960s and ‘70s Montana serial killer motivated by control and sadism, and the brutal deaths of innocent children and at least one young woman that followed. Throughout the first half of this artfully unfurled history, the killer lurks, faceless in the shadows, analogous to our worst fears and dread’s sickening encroachment.

‘Her Voice in the Dark’

The murder spree started with a seemingly accidental child death in 1967, followed by a sinister but unsolved one in 1968, in the tiny town of Manhattan, Montana.

Then in 1973, a beloved 7-year-old named Susie Jaeger vanished from her family camp tent – not far from Manhattan – through a perfectly-sliced semicircle slit.

The little girl’s disappearance drove many journalists to their desks for the year it took to unravel the mystery of her abduction.

But nearly 50 years later, she called to just one more.

“When Susie Jaeger became real to me – when I thought I could hear her voice in the dark—I knew I’d write ‘ShadowMan,’” Franscell told Cowboy State Daily.

And he did.

But it took interviews with more than 150 people, sifting through about 13,000 FBI documents, knocking on doors and touring crime scenes again and again, for about two years.

“I’m an old-school journalist. I believe truly, madly, deeply in being there,” where the events happened, said Franscell, adding that he “looked for that narrative dust that settles on everything. It’s that textual grit that makes it real.”

Although the outcome of this story was decided long before Franscell, the first true-crime writer to take it on, reached for his pen, its aching suspense was hidden in the data. For the author – and consequently the reader – sources became characters, quotes became dialogue; 50 years of buried memories surrendered their heartbreak.

A Science is Born

But the dark recesses of that tragedy called forth a light that remains: the science of FBI profiling. Two of the book’s heroes, Patrick Mullaney and Howard Teten, created the Behavioral Science Unit of the FBI to draw psychological patterns from known evidence in particularly egregious cases. And they tested their craft on this one.

“I was most surprised that in 50 years there’s never been a book about these ghastly crimes or the origin story of profiling,” said Franscell. “A lot of true-crime buffs had never heard of it.”

Perhaps that shock is greater when one considers that man’s exposure to crime through the constant news inundation of the day still has not sated curiosity toward the criminal mind.

“The platforms are constantly evolving, but the obsession with real crime stories is ancient,” Franscell said. “The criminal mind has always fascinated us. When an especially deviant crime happens, our rational minds want to put things back in order, to make sense out of something senseless.”

‘Greater Human Stories’

The futile chasm of criminal thought is where Franscell dug for heroism.

“Very quickly, I recognized this case’s power was universal stuff like a mother’s love, persistence,” he said.

And in the frantic 1973 investigation and the manhunt that followed, those heroic traits struggled through blood and mystery. But they didn’t vanish.

Susie Jaeger’s mother, Marietta, took an active part in the complex plot to entrap her daughter’s kidnapper and killer. She spent hours on the phone with him, letting him play mind games on her so that she could give the profilers the voice and behavioral evidence they needed. Just days before his arrest, she looked him in the eye, shook his hand, and told him frankly that she knew what he’d done.

And in the end, she forgave him.

Marietta Jaeger’s courage and the investigators’ doggedness, Franscell said, are the real story.

“I’m not especially fascinated by serial killers, except as the catalysts that set greater human stories in motion,” he said. “I’m far more interested in the people who are splashed by this horror, and those who must deal with it.”

And so, “ShadowMan” paints a picture of a town that keeps moving on. Brilliant psychologists who use their mental gifts to dissect atrocities. An older sister who can’t forget the moment the air inside the family tent changed. An FBI special agent as sturdy and rugged as the vast Western landscape that hid his adversary’s gory leavings. A sheriff’s deputy who waded into human excrement to find the truth.

And a mother who never gave up on finding some meaning greater than herself, greater than her loss, and greater than the drenching shadow of cruelty itself.

About the Author

Franscell, 65, grew up in Wyoming as a newsroom kid in a newspaper family and was a longtime editor of the Gillette News Record.

As a senior writer for the Denver Post, he was sent to cover the Middle East shortly after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, in the early phases of the Afghan War. He also covered Hurricane Rita on scene.

He and his wife now live in New Mexico.

Franscell’s first book was an acclaimed literary fiction work, “Angel Fire,” published in 1998. He kicked out two more works of fiction, “The Deadline,” and “The Obituary.”

But in the early 2000s, Franscell circled back to a criminal tragedy that had impacted him right at home at age 16, when his childhood friends from Casper, half-sisters Becky Thomson and Amy Burridge, were attacked by two men and taken to the Fremont Canyon Bridge. The men threw Burridge off the bridge and violently raped Thomson, who fell, or jumped, to her own death from the same bridge 19 years later.

He wrote “The Darkest Night,” which published in 2007 and launched his career in true crime.

Wyoming, Again

In 2019 Franscell published another well-known Wyoming crime tale, “Alice & Gerald: A Homicidal Love Story,” about Gerald and Alice Uden. The Udens wed after Alice already had murdered at least one prior husband.

During their marriage, Gerald Uden killed his ex-wife Virginia and two adopted sons Richard and Reagan in 1980 near Pavillion, Wyoming, reportedly at his wife’s urging.

The pair remained married and evaded arrest for decades before they were convicted of murder in 2013 (Gerald) and 2014 (Alice).

After Alice Uden’s 2019 death – and after Franscell’s book about them had already been released – Gerald Uden wrote a letter to Franscell from within the Wyoming Medium Correctional Institution in Torrington, claiming that his wife had been the actual “murderess” in the case.